(2022) Second Place: Growth and Fixed Mindsets: A Survey About Mindsets and Their Relationship to Symptoms of Mental Illness, the Internalization of Problems, and Emotion Regulation Strategies

by Kennedy Cole

Abstract

Mindsets, whether fixed or growth, are extremely powerful frameworks that influence nearly every aspect of individuals and their lives. Consistent with prior research, to determine the impact of these mindsets on college students, we considered the relationship between mindsets and mental health symptoms, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies. Findings indicate individuals with fixed mindsets experienced less severe symptoms of depression; however, an individual’s mindset does not influence the internalization of their problems or the emotion regulation strategies they use. Because this study resulted in insights contrary to previous research on this topic, and that the data upon which this study is based was self-reported, there is a possibility that it might be biased and/or inaccurate. Additionally, other aspects, such as background, culture, and life experiences, were not considered or examined. Furthermore, because of the small sample sizes (22 participants per mindset) Type I and II errors could have been made. This study allowed for a deeper understanding of this area and hopefully will provoke more in-depth research of this topic. To improve internal validity, we suggest an experiment be conducted. If mindsets influence and impact the variables investigated, it is important to determine this to help ensure that individuals have and maintain positive mental well-being.

Keywords: growth mindset, fixed mindset, symptoms of mental illness, reappraisal coping strategy, suppression coping strategy, emotion regulation strategies

Strategies

Within the past few decades, research began on growth and fixed mindsets’ impact on individuals’ academic and psychological functioning. Mindsets create psychological worlds or meaning systems that are extremely powerful and shape how people process information, their reactions to events, and influence many important aspects of their life, including self-regulation, self-esteem, and social perception (Schleider & Weisz 2018; Sun et al., 2020). Furthermore, these mindsets can affect an individual’s academic success by influencing the mastery of goals, perception of intrinsic and extraneous loads, retention of the learned information, and transfer performance (Xu et al., 2021). Individuals with growth mindsets believe their traits, such as intelligence, are malleable through effort; whereas individuals with fixed mindsets believe their traits are innate. Maladaptive belief systems, such as fixed mindsets, can have negative consequences, including causing individuals to question their abilities, use unhealthy coping mechanisms, and experience more intense feelings of helplessness (Schleider et al., 2016). These negative consequences of maladaptive belief systems can lead to the onset of symptoms of emotional problems such as perfectionism, anxiety, and/or depression (Schleider et al., 2016; Shroder et al., 2015).

Mindsets can be predictors of mental illness, influence emotion regulation strategies, correlate to intellectual humility, and contribute to academic success (Burnette et al., 2018; Porter & Schumann 2018; Shroder et al., 2015). Individuals with a fixed mindset, often have worse mental health and mental illness symptoms. Furthermore, individuals with fixed mindsets more often have negative emotion regulation strategies, such as suppression, hiding and/or ignoring one’s emotions; whereas individuals with a growth mindset have a higher frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, or adapting how one thinks (Schleider et al. 2016). Individuals with a growth mindset demonstrate more intellectual humility compared to individuals with a fixed mindset (Porter & Schumann 2018). Growth mindsets result in increases in positive academic attitudes, motivation, and perception of academic competence, which leads to improved learning efficacy and correlates to higher grades (Burnette et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2017).

This study was conducted to determine how growth and fixed mindsets: relate to symptoms of mental illness; the internalization of problems; and emotion regulation strategies. Previous research has shown that growth mindsets are positive, can be extremely beneficial, and can lead to increases in mental health, positive emotion regulation mechanisms, and decreases in the internalization of problems. To collect data for this study, a survey that focused on the relationship that growth and fixed mindsets have on symptoms of mental illness, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies was distributed to College of Western Idaho (CWI) students currently enrolled in a Psychology (PSYC) class. This study was necessary because it allowed for a deeper understanding of how these mindsets affect individuals, specifically college students. Based on existing research, it was hypothesized that individuals with growth mindsets: have less severe symptoms of mental illness and experience a decrease in their existing mental health symptoms; experience a decrease in the internalization of problems; and have a higher frequency of utilizing positive emotion regulation strategies.

The general research question asks, “What is the difference between growth and fixed mindsets and their relation to symptoms of mental illness, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies.” Specific hypotheses include:

H1: Individuals with growth mindsets will differ compared to fixed mindsets on the severity of their depression symptoms.

H2: Individuals with growth mindsets will differ compared to fixed mindsets in preferring talk therapy to treat mental health symptoms.

H3: Individuals with fixed mindsets will differ compared to growth mindsets in preferring medications to treat mental health symptoms.

H4: Individuals with growth mindsets will differ in the internalization of their problems compared to individuals with fixed mindsets.

H5: Individuals with growth mindsets will have a higher frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies compared to individuals with fixed mindsets.

To collect data, we used a survey which allowed for relatively easy and timely remote distribution, collecting a wide range of data, in a cost-effective manner.

Method

Participants

The participants included 7 non-binary, 33 male, and 93 female students whose ages ranged from 18 to 49 and were enrolled in a PSYC class at CWI during the 2021 fall semester.

Measures Ten questions were developed to determine growth and fixed mindsets’ relationship to mental illness symptoms, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies. To obtain more accurate information and to determine the severity of the impact these mindsets have, a Likert scale was used for all ten questions. For the complete list of survey questions, refer to Appendix A.

Procedure

To obtain participants, an email that included the survey link and information about the study was distributed to the CWI PSYC faculty by Professor Jana McCurdy. The faculty then disseminated the survey amongst their classes and encouraged student participation by offering course credit. If the students did not want to participate in the survey, another option for course credit was presented.

To develop, design, and distribute the password-protected survey, Google Forms was used. The first page of the survey consisted of the consent form and by clicking “next”, participants confirmed they were a minimum of 18 years old, had read and understood the consent form, and agreed to be a participant.

Once distributed, the survey was available to students for 13 days; the data was anonymously collected, and no identifiable information was used or recorded. While the survey remained available to students, the faculty advisor was the only one who could review the data. After the survey was no longer available, through a password-protected email, the data was distributed amongst team members, stored on a password-protected server, and will be destroyed after 5 years. Participants were divided into two groups based upon their responses to four questions: when I succeed, I believe it is mainly because of my work ethic; when I succeed, I believe it is mainly because of my innate (traits you are born with) abilities; when I fail, I believe it is because of a lack of ability; and when I fail, I view it as an opportunity to learn.

Three data points were identified and cleaned. First, regarding question number one (“I believe my traits, such as my intelligence, can improve over time with practice and hard work.”), out of the 133 total participants, only one person said no. Because of this, their data was determined to be insufficient to determine mindset; and therefore, this question was eliminated. Second, regarding question number three (“On average, for each class, I roughly spend __ hours on my homework per class every week.”), all answers were changed to the middle point if a range was provided (e.g., 3.5). Third, and finally, regarding question number 28 (What age are you?), nine individuals reported that they were under the age of 18 and two individuals did not report their age; therefore, their data was removed because they did not meet the appropriate age criteria.

Results

It was hypothesized that there would be a difference in symptoms of depression based on an individual’s mindset. To test this hypothesis, data were collected from a total of 44 participants. Participants were divided into two categories of mindsets: growth (n = 22, M = 4.14, SD = 1.13), and fixed (n = 22, M = 3.05, SD = 1.53). On average, participants’ overall score for symptoms of depression was 3.47 (SD = 1.39) on a Likert scale of 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Overall symptoms of depression did significantly differ between individuals’ mindset as indicated by a One Way ANOVA, F(1, 19) = 3.81, p = .025 (see Table 1). Comparison of the means of the two groups showed that individuals with growth mindsets had more severe symptoms of depression compared to individuals with fixed mindsets.

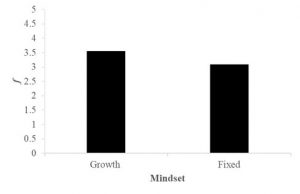

It was also hypothesized that there would be a difference in individuals’ internalization of their problems based upon their mindset. On average, participants’ overall score for the internalization of their problems was 3.38 (SD = 1.23), 3.55 (SD = 1.18 ) for growth, and 3.09 (SD = 1.41) for fixed, on a Likert scale of 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Overall, the internalization of problems did not significantly differ between individuals’ mindsets as indicated by a One Way ANOVA, F(1, 19) = .82, p = .441 (see Figure 1).

It was further hypothesized that there would be a difference in the frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies based on an individual’s mindset. On average, participants’ overall frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies was 3.54 (SD = 1.20), 3.27 (SD = 1.42) for growth, and 3.77 (SD = 1.15) for fixed, on a Likert scale of 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Overall, the frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies did not significantly differ between individuals’ mindsets as indicated by a One Way ANOVA, F(1,19) = .96, p = .387 (see Table 2).

Discussion

A significant difference was found between fixed and growth mindsets regarding the influence on symptoms of depression. Surprisingly, individuals with fixed mindsets reported less severe symptoms of depression compared to growth mindsets. This result is concerning because it is contrary to all previous literature on growth and fixed mindsets’ relationship to mental illness. Previous studies have demonstrated that individuals with growth mindsets often experience less severe symptoms of depression and better overall mental health compared to individuals with fixed mindsets (Schleider et al., 2016; Schleider & Weisz 2018; Shroder et al., 2015). However, this difference in findings could be because previous studies used the method of an experiment instead of a survey.

The hypothesis that individuals with growth mindsets will differ in the internalization of their problems compared to individuals with fixed mindsets was not supported. It was shown that individuals’ mindsets do not influence the severity or frequency of the internalization of their problems. This finding is disconcerting because previous research has shown that individuals with fixed mindsets correlate to a higher frequency and more severe internalization of their problems (Schleider et al., 2016). However, in previous literature the participants were adolescents rather than college students, and larger sample sizes were utilized; and therefore, this could explain the difference in results between the existing literature and this study.

After testing the hypothesis that individuals with growth mindsets will have a higher frequency of using positive emotion regulation strategies compared to individuals with fixed mindsets, an insignificant difference was found. The results demonstrated that an individual’s mindset, fixed or growth, does not influence the type of emotion regulation strategies they use. These findings are contrary to previous research showing that individuals with fixed mindsets correlate to a higher frequency of using suppression, whereas individuals with growth mindsets correlate to a higher frequency of using reappraisal (Schleider et al., 2016). A possible explanation for the difference in these results could be because of inadequate wording of the questions and/or a Likert scale was used.

Methodological Limitations

Because only CWI PSYC students were asked to participate in the study, convenience sampling was used. Additionally, since the data was self-reported and individuals want to be viewed as socially acceptable, this allowed for the possibility of inaccurate and/or biased data. Also, because individuals’ mindsets can change daily, just one survey may not be enough to determine mindsets’ relationship to mental illness symptoms, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies. In addition, this study did not consider or examine how different cultures, backgrounds, and life experiences may affect mindsets and their relationship to the variables investigated. Furthermore, because of questions related to mental health and how severe the symptoms are, there is a possibility that participants could have experienced emotional distress either during or after the survey.

Statistical Limitations

One possible statistical limitation was the small sample size of each group, because they are not representative of the population, and increases the possibility for margin of error.

Additionally, all three dependent variables were ordinal data that were treated as interval ratio (IR) data, which violates a requirement of the One Way ANOVA. Also, for the findings on symptoms of depression, a Type I error may have been made, which could have caused an inaccurate rejection of the null hypothesis. Furthermore, for the results of the internalization of problems and emotion regulation strategies, a Type II error could have been made, which may have caused the acceptance of the null hypothesis, when in actuality it is false.

Conclusion

This study was valuable because it allowed for a deeper understanding of how growth and fixed mindsets influence depression symptoms, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies among college students. Because all findings are contrary to previous literature, more in-depth research should be conducted to determine the influence that mindsets have on the variables explored. In future studies, the method of an experiment may be more adequate and beneficial to determine and more fully understand the impact that mindsets have. If mindsets influence and impact symptoms of mental illness, the internalization of problems, and emotion regulation strategies, it is important to clearly determine this to help ensure that individuals have and maintain positive mental well-being.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Symptoms of Depression

| Mindset | n | M | SD | F |

| Growth | 22 | 4.14 | 1.13 | *3.81 |

| Fixed | 22 | 3.05 | 1.53 | — |

* p = .025

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for Positive Emotion Regulation Strategies

| Mindset | n | M | SD | F |

| Growth | 22 | 4.14 | 1.13 | *.96 |

| Fixed | 22 | 3.05 | 1.53 | — |

* p = .387

Figure 1

Frequency of the Internalization of Problems

Appendix A

Survey Questions on Growth Mindsets Relation to Mental Illness Symptoms, the Internalization of Problems, and Emotion Regulation Strategies

- I frequently experience one or more of the feelings listed: hopelessness and/or sadness, low self-esteem issues, lack of motivation, and/or have little or no interest or pleasure in completing normal activities.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

2. If you experience one or more of the feelings listed above, how difficult does it make your life?

- Not difficult at all, somewhat difficult, very difficult, extremely difficult

3. I frequently experience one or more of the feelings listed: nervousness, restlessness, and/or having difficulty controlling how much I worry about things.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

4. If you experience one or more of the feelings listed above, how difficult does it make your life?

- Not difficult at all, somewhat difficult, very difficult, extremely difficult

5. To treat mental health symptoms, I would prefer talk therapy over medications.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

6. I believe, to treat mental health symptoms, medications are necessary.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

7. I rarely talk about my problems or share my concerns with others.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

8. When something goes wrong, I often believe it is my fault.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

9. When I am emotionally upset, to calm myself down, I usually change my thinking.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

10. When I am emotionally upset, I often try to not show my emotions and ignore what is bothering me.

- Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neutral, Somewhat Agree, Agree

References

Burnette, J. L., Russell, M. V., Hoyt, C. L., Orvidas, K., & Widman, L. (2018). An online growth mindset intervention in a sample of rural adolescent girls. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 428-445. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12192

Cook, E. M., Wildschut, T., & Thomaes, S. (2017). Understanding adolescent shame and pride at school: Mind-sets and perceptions of academic competence. Educational & Child Psychology, 34(3), 119-129.

Porter, T., & Schumann, K. (2018). Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view. Self & Identity, 17(2), 139-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2017.1361861

Schleider, J., & Weisz, J. (2018). A single-session growth mindset intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: 9-month outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 59(2), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.1281

Schleider, J. L., Schroder, H. S., Lo, S. L., Fisher, M., Danovitch, J. H., Weisz, J. R., & Moser, J. S. (2016). Parents’ intelligence mindsets relate to child internalizing problems: Moderation through child gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 3627-3636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0513-7

Schroder, H. S., Dawood, S., Yalch, M. M., Donnellan, B. M., & Moser, J. S. (2015). The role of implicit theories in mental health symptoms, emotion regulation, and hypothetical treatment choices in college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(2),120-139.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9652-6

Sun, L., Li, J., & Hu, Y. (2020). I cannot change, so I buy who I am: How mindset predicts conspicuous consumption. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 48(7), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.9314

Xu, K. M., Koorn, P., de Koning, B., Skuballa, I. T., Lin, L., Henderikx, M., Marsh, H. W., Sweller, J., & Paas, F. (2021). A growth mindset lowers perceived cognitive load and improves learning: Integrating motivation to cognitive load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(6), 1177–1191. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000631