(2022) First Place: Surveying Psychology Students: Analyzing Attachment Theory and How it Impacts Romantic Relationships

by Sawyer Ellis, Yeva Veraksa, Olivia Vargas, Kareli Mata, & Saige Self

Abstract

Childhood development plays a significant role in romantic relationships. The purpose of this study is to explore childhood development and if parent-child attachment predicts insecure behaviors: including impulsive, possessive, and habit formatting tendencies in adult romantic relationships. Even further, the relationship between parental substance uses and offspring adult attachment styles. This study explores if insecure attachment styles can negatively affect romantic relationships and if parents’ alcohol consumption is related to offspring’s insecure attachment style. College students were asked to rate their impulsive behavior along with their partner’s possessive traits. The results concluded further research is needed to determine possessive & impulsive behavior. Specifically, what causes insecure attachment in relationships and if substance dependency is the root cause of partner unsatisfaction.

Keywords: impulsive behavior, possessive behavior, parental substance use, adult attachment, parent-child attachment, anxiously attached, avoidant attachment, secure attachment

Relationships have many factors that play a role in the success that you and your partner will have together. Relationship attachment styles have influenced the satisfaction of each partner. Those with deactivation attachment style, the emotional withdrawal from a partner when under distress, felt unsatisfied in romantic relationships but those with hyperactivation attachment style felt no difference in their relationship (Mondor et al., 2011). In surveys done of married couples, researchers found that after at least two years of marriage, distress appeared in the marriage (Sibley & Liu., 2006). Distress in marriage, especially those with children, can deflect those emotions onto them.

Attachment theories allow us to better understand the behavioral dynamic in romantic relationships and may even predict the relationship length. It is important to understand why some relationships last longer than others, especially when a child is involved (Barbaro et al., 2016). One study found that neglected children avoided their distress in adulthood. Later, these anxious individuals projected distress onto their own children (Julal & Carnelley, 2012). In essence, children are influenced through relationships, parents, friendships, etc. in their life and the big question is to research what causes this.

How a parent raises their child and what they expose them to is a great indicator of the child’s attachment style (Roeofs et al., 2008). Research found that children in later years respond similarly to their parents when given alike situations. A caregiver’s romantic relationship can affect the flow of family day-to-day life. Low levels of anxiety and avoidance in a relationship can lead to a more harmonious family life and higher marital satisfaction (Pedro et al., 2015). In unhappy marriages, parents bring in the child as a third-party buffer which can lead to traumatic childhood experiences. It would be helpful to know if overly exposed children mimic their parents’ insecure traits in their adult relationships. If so, what measures does one take to prevent this from happening?

The general research question asks, “What is the relationship between parenting styles and their children’s adult attachment styles later in life?”

H1: Parent-child attachment is related to impulsive behavior in adulthood.

H2: There is a relationship between parental substance use and offspring adult attachment style.

H3: Partners’ possessive behaviors are predicted by attachment style.

PSYC 101 professors will encourage their students to participate in the survey, and to reward student participation with course credit. The participants of this study will be current College of Western Idaho students enrolled in Psychology 101. The consent form will be attached at the beginning of the survey. The surveys will be conducted online through Google Forms. No names or personal identifiers will be collected. Information will be stored in a password-protected database and data will be destroyed after five years.

Method

Participants

A total of 44 psychology students participated in our research study at The College of Western Idaho fall of 2021. Seven identified as male and 35 identified as female. Only two were identified as nonbinary. The student’s ages ranged from 18 – 42.

Measures

Our survey had a total of 65 questions. Sixteen of these questions were with reference to possessive, impulsive, and addictive behaviors regarding students’ romantic partners, caregivers, or themselves (see Appendix A). The rest of the questions pertained to parenting styles, participants’ relationships with caregivers, and romantic partners. The answers to our survey questions were in the form of a 1-10 satisfaction or dissatisfaction scale, Likert scale 1-5, and free response.

Procedure

PSYC 101 professors encouraged their students to participate in the survey and to reward student participation with course credit. The participants of this study were College of Western Idaho Psychology 101 students. At the beginning of the survey, a consent form was attached verifying the participant was at least 18 years of age. If a student was under the age of 18, they were unable to complete the survey and were given a different assignment to earn extra credit. Each student participating in our research study had 11 days to submit feedback. The survey was conducted online through Google Forms. No names or personal identifiers were collected. Information is stored in a password-protected database and data will be destroyed after five years. Once the student completed the survey, they were instructed to screenshot completion for proof. They were asked to submit the image to the online learning platform Blackboard. Free counseling was offered to participants affected by our survey questions.

Once our research team received survey feedback, we cleaned the data. We made changes to the variables to better understand and identify our questions. This made it easier to run our analysis. Next, we threw out data that was not related to our survey question. For example, a few participants mixed up the free-response questions with questions asking to identify parent one and two. We eliminated one answer that stated, “it’s none of your business”. Our group input zero for participants who were not in a relationship, or the question was not applicable.

Results

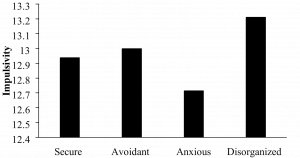

The first hypothesis was parent-child attachment is related to impulsive behavior in adulthood. To test this hypothesis, data were collected from a total of 44 college students.

Participants were divided into four categories of parent-child attachment: anxious (n = 7, M =12.71, SD = 4.19), avoidant (n = 2, M = 13.00, SD = 7.07), secure (n = 16, M = 12.94, SD =2.40), and disorganized (n = 19, M = 13.21, SD = 4.54). On average, the participants scored 13.00 (SD = 3.78) on the impulsive behavior scale (scores ranged from 5 – 19). There was no significant difference found between parent-child attachment and impulsive behavior in adulthood, as indicated by a One Way ANOVA, F(3, 4.32) = 0.02, p = .99 (see Figure 1). The second hypothesis was there is a relationship between parental substance use and offspring adult attachment style. To test this hypothesis, data were collected from 44 college students. Participants were divided into three categories based on their adult attachment style: avoidant (n = 20, M = 4.35, SD = 0.88), secure (n = 16, M = 3.88, SD = 1.36), and anxious (n = 8, M = 3.25, SD = 1.58). On average the participants scored 3.98 (SD = 1.25) on their parents’ alcohol consumption use (scores ranged from 1 – 5). There was no significance found between participants adult attachment style and their parents’ alcohol consumption, as indicated by a One Way ANOVA, F(2, 16.2) = 2.06, p = .16 (see Table 1).

It was hypothesized partners’ possessive behaviors are predicted by attachment style. Data were collected from 44 college students. On average, participants reported partners’ attachment style 3.38 (SD = 0.95) and their possessive behavior (scores ranged 0 – 5) 3.33 (SD = 1.45). To test the relationship between a partners’ possessive behavior and their attachment style, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. There was no significance found, r(35) = -.04, p =.820.

Discussion

Our first hypothesis that parent-child attachment is related to impulsive behavior in adulthood was unfounded. There is little research if impulsive behavior is tied to attachment theory. Impulsivity in most research studies is measured by instant gratification. For instance, the gift task delay experiment. In this observation, children under the age of four were tempted with a beautiful Christmas present (Mittal et al., 2013). The caregiver told their child not to touch the gift and left the room. The study found anxious ambivalent children had no problem resisting the present because they did not rely on their caregivers to parent them. They parented themselves (Mittal et al., 2013). To measure parent-child attachment style, the stranger in the room situation was performed. I used questions regarding the stranger in the room experiment (see Appendix A). It has been found that the way a child reacts to their caregiver leaving the room determines temperament and attachment style (Mittal et al., 2013). Although the results of my study were not significant, it did open the door to further exploration. I found that anxiously attached participants in our study scored the highest on the impulsivity scale. Focusing on anxiously attached children and comparing them to anxious adults may show significance. Our second hypothesis, there is a relationship between parental substance use and offspring adult attachment style, was unfounded. In past research studies, it has been found that attachment theory is a predictor of developing alcohol dependency (Hazarika & Bhagabati, 2018). Specifically, the dynamic between father and son in families of alcohol dependency versus nonalcoholic families. The study concluded that individuals who were securely attached found emotional support while insecurely attached individuals sought other means; In this circumstance alcohol (Hazarika & Bhagabati, 2018). Although my findings were not significant, I found the average of anxiously attached individuals’ parents drank somewhat often. I did not ask questions about the participant’s alcohol consumption, considering some students are under the legal age to drink. Past research studies are mostly tied to father and son relationships (Hazarika & Bhagabati, 2018). Exploring all genders may give researchers more information on how to help support individuals who want to stop or reduce alcohol consumption.

Our last hypothesis found partners’ possessive behavior is predicted by attachment style was unfounded. I was hopeful but not surprised by the output. Research has a difficult time determining what exactly defines a romantic partner to be possessive (Craddock, 1997). Considering attachment styles have a different definition of controlling behaviors. However, one study found in marriages there is an expectation of privacy and respecting the property of your spouse positively impacts marriage satisfaction. On the other hand, the study was conducted in the late 90s and called for further research (Craddock, 1997). Although my findings were contrary to this specific experiment, measuring and understanding what possessive behavior looks like in romantic relationships may give researchers a clue if lack of privacy is a cause for divorce.

Methodological Limitations

My portion of the survey was less reliable and required knowledge of childhood. For example, I asked questions pertaining to how the participant responded to their caregiver after leaving them alone in the room with a stranger. Some individuals have a better memory of their childhood than others. The participants may have felt influenced to answer dishonestly because of social pressure and sociocultural differences. We listed questions related to childhood at the end of the survey, which would give the participant enough knowledge of parent-child attachment. Our survey relied on self-report instead of observations. The demographics were primarily young adults, mostly female.

Statistical Limitations

One statistical limitation of this study is no equal variance between groups, meaning the population variances differed. The skewness of partner possessive behavior and the participants parent-child attachment style were negatively skewed and violated the assumptions of a one-way ANOVA. Normal distribution is important because data near the mean shows the most frequency; in which the population is normally distributed.

Studying impulsivity, possessive, and habit formatting behavior is important to study and needs further research. To illustrate, researching parent-child attachment may innovate specialized support groups for adults on the road to recovery. It may determine an effective way of managing alcohol consumption. Attachment theory may also explain why individuals stay in unsatisfied relationships where possessive behavior is present. Finding answers may give researchers more information about impulsive behavior and if impulsivity is or is not the source of possessive relationships. This information may educate psychology branches such as victims’ advocates on how to give proper guidance and resources to victims who want a way out of a possessive relationship.

Table 1

Attachment Style based on Parents Alcohol Consumption

| Attachment style | n | M | SD |

| Avoidant | 20 | 4.35 | 0.875 |

| Secure | 16 | 3.88 | 1.360 |

| Anxious | 8 | 3.25 | 1.581 |

Note. A Likert scale was used to measure how often participants’ parents would drink (p = .16).

Figure 1

Relationship between Parent-Child Attachment Style and Impulsivity

Appendix A

Survey Questions Analyzing Attachment Theory and How it Impacts Romantic Relationships

1. I often purchase things without thinking

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

2. I engage in risky behavior before considering the consequences

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

3. I interrupt conversations

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

4. I am impatient

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

5. My father drinks alcohol often

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

6. My mother drinks alcohol often

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

7. My parent/caregiver behavior is uncontrollable when drinking

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

8. My father purchase things without thinking

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

9. My Mother purchases things without thinking

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

10. My father says things he regrets

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

11. My mother says things she regrets

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

12. My partner wants to spend time with me even if I don’t want to

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

13. My partner believes my property belongs to him too

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

14. My partner invades my privacy

(Strongly agree somewhat agree neither somewhat disagree strongly disagree)

15. Choose one that best applies to you (Multiple choice)

A. I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.

B. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.

C. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.

16. What is your age?

17. What is your gender?

18. If your parent left you alone with a stranger in the room, how would you react? (Multiple choice)

A. Feel extremely distressed and chase after parent

B. Have no emotion

C. Feel somewhat distressed yet still explore the room

19. When my parent returns to the room I would most likely (Multiple choice)

A. Feel angry at the parent for leaving me with said stranger

B. Ignore parents’ arrival

C. Feel happy upon parent arrival

References

Barbaro, N., Pham, M. N., Shackelford, T. K., & Zeigler, H. V. (2016). Insecure romantic attachment dimensions and frequency of mate retention behaviors. Personal Relationships, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12146

Craddock, A. E. (1997). The measurement of privacy preferences within marital relationships: The relationship privacy preference scale. American Journal of Family Therapy, 25(1),48–54. https://doi-org/10.1080/01926189708251054

Hazarika, M., & Bhagabati, D. (2018). Father and son attachment styles in alcoholic and nonalcoholic families. Open Journal of Psychiatry & Allied Sciences, 9(1), 15–19. https://doi-org/10.5958/2394-2061.2018.00003.4

Julal, F. S., & Carnelley, K. B. (2012). Attachment, perceptions of care and caregiving to romantic partners and friends. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(7).https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1914

Mittal, R., Russell, B. S., Britner, P. A., & Peake, P. K. (2013). Delay of gratification in two- and three-year-olds: Associations with attachment, personality, and temperament. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(4), 479–489. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9600-6

Mondor, J., McDuff, P., Lussier, Y., & Wright, J. (2011). Couples in therapy: Actor-partner analyses of the relationships between adult romantic attachment and marital satisfaction.

American Journal of Family Therapy, 39(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2010.530163

Pedro, M., Ribeiro, T., & Shelton, K. (2015). Romantic attachment and family functioning: The mediating role of marital satisfaction. Journal of Child & Family Studies,24(11).https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0150-6

Roelofs, J., Meesters, C., & Muris, P. (2008). Correlates of self-reported attachment insecurity in children: The role of parental romantic attachment status and rearing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17(4), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-007-9174-x

Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2006). Working models of romantic attachment and the subjective quality of social interactions across relational contexts. Personal Relationships,13(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00116.x