A Beginner’s Guide to Gothic Architecture

This chapter contains:

Beginner’s guide to Gothic Architecture

Sculpture and Portable Objects

Italy, Germany, and the Czech Republic

“Ile-de-France”; “in the French manner”

lux nova

Notre Dame = Our Lady

pointed arch

ribbed vaults

flying buttress

piers and colonettes

lancet windows

rose window

bar tracery

triforium

clerestory

Gallery of Kings

harmonic facade

jamb figures

The style represented giant steps away from the previous, relatively basic building systems that had prevailed. The Gothic grew out of the Romanesque architectural style, when both prosperity and relative peace allowed for several centuries of cultural development and great building schemes. From roughly 1000 to 1400, several significant cathedrals and churches were built, particularly in Britain and France, offering architects and masons a chance to work out ever more complex and daring designs.

The most fundamental element of the Gothic style of architecture is the pointed arch, which was likely borrowed from Islamic architecture that would have been seen in Spain at this time. The pointed arch relieved some of the thrust, and therefore, the stress on other structural elements. It then became possible to reduce the size of the columns or piers that supported the arch.

So, rather than having massive, drum-like columns as in the Romanesque churches, the new columns could be more slender. This slimness was repeated in the upper levels of the nave, so that the gallery and clerestory would not seem to overpower the lower arcade. In fact, the column basically continued all the way to the roof, and became part of the vault.

In the vault, the pointed arch could be seen in three dimensions where the ribbed vaulting met in the center of the ceiling of each bay. This ribbed vaulting is another distinguishing feature of Gothic architecture. However, it should be noted that prototypes for the pointed arches and ribbed vaulting were seen first in late-Romanesque buildings.

The new understanding of architecture and design led to more fantastic examples of vaulting and ornamentation, and the Early Gothic or Lancet style (from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) developed into the Decorated or Rayonnant Gothic (roughly fourteenth century). The ornate stonework that held the windows–called tracery–became more florid, and other stonework even more exuberant.

The ribbed vaulting became more complicated and was crossed with lierne ribs into complex webs, or the addition of cross ribs, called tierceron. As the decoration developed further, the Perpendicular or International Gothic took over (fifteenth century). Fan vaulting decorated half-conoid shapes extending from the tops of the columnar ribs.

The slender columns and lighter systems of thrust allowed for larger windows and more light. The windows, tracery, carvings, and ribs make up a dizzying display of decoration that one encounters in a Gothic church. In late Gothic buildings, almost every surface is decorated. Although such a building as a whole is ordered and coherent, the profusion of shapes and patterns can make a sense of order difficult to discern at first glance.

After the great flowering of Gothic style, tastes again shifted back to the neat, straight lines and rational geometry of the Classical era. It was in the Renaissance that the name Gothic came to be applied to this medieval style that seemed vulgar to Renaissance sensibilities. It is still the term we use today, though hopefully without the implied insult, which negates the amazing leaps of imagination and engineering that were required to build such edifices.

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in Beverley Minster, England, 1190–1420 URL: https://youtu.be/G94jFWH8NSM

Gothic Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Source: Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Valerie Spanswick, “Gothic architecture, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, January 25, 2023, accessed November 4, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/gothic-architecture-an-introduction/.

Ambulatory, Basilica of St. Denis, Paris, 1140-44

Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres, c.1145 and 1194-c.1220, Chartres (France)

URL: https://youtu.be/Jk3VsinLgvc

Chartres Cathedral on Google Maps

Chartres Cathedral on Mapping Gothic France

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres,” in Smarthistory, December 18, 2015, accessed November 18, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/cathedral-of-notre-dame-de-chartres-part-1-of-3/.

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt — and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 BCE). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame … was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.” [1]

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

Additional resources:

The Cathedral’s construction (official website of Notre Dame de Paris)

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris,” in Smarthistory, April 24, 2019, accessed November 11, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/notre-dame-fire/.

Reims Cathedral (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims), begun 1211, Reims, France URL: https://youtu.be/9STNgMoRXHM

See also:

URL:https://youtu.be/xsHYPNYmJCs

With its two soaring towers and three large portals filled with sculpture, Amiens Cathedral crowns the northern French city of Amiens. The cathedral is still one of the tallest structures in the city, its spire climbing nearly 400 feet into the air. You can see the skeletal stone structure on the exterior of the church, where flying buttresses support the upper walls like spider legs or a ribcage. The lace-like façade is made up of slender colonnettes and screen-like openings, heightening the contrast of light and shadow. Deeply set portals topped with tall gables pull the viewer in, an invitation to approach the building and cross the threshold.

Flying buttresses highlighted in red, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Through a series of intertwined images, each portal tells a story important to the Christian Church and the local Christian community through its stately sculpture. Within these portals, there is a whole sculpted universe to discover, with a multitude of figures, creatures, and narrative scenes, large and small. Some art historians have called this façade a sermon wrought in stone. If you visit the right portal, you will see images from the life of the Virgin Mary; in the left portal, you’ll find the story of Saint Firmin, the first bishop of Amiens, and images of local saints. Let’s take a closer look at the central portal.

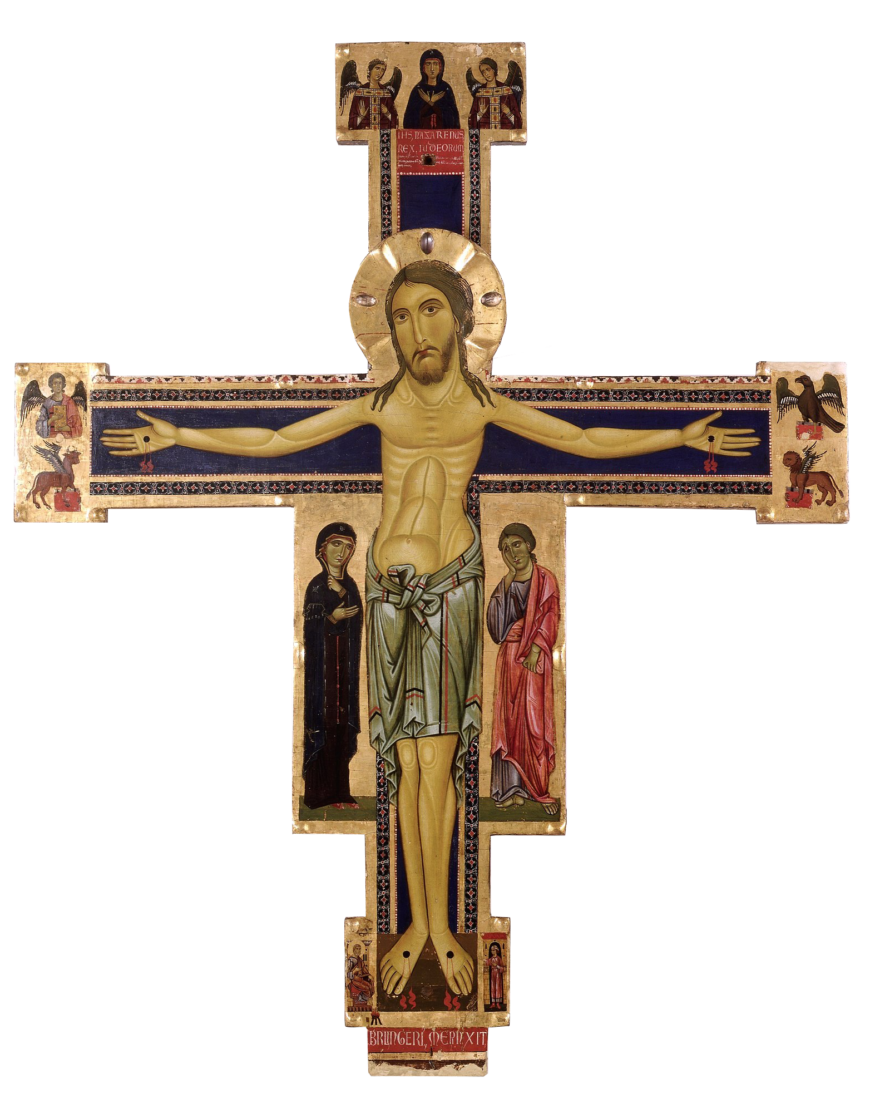

The central portal announces its importance through its emphasized height and width. This is where you will find the trumeau figure of Christ—the Beau Dieu, or beautiful God—surrounded by the twelve apostles. You’ll notice that the figures on the portal at Amiens are sculpted with a high degree of realism, and that their heavy drapery hangs in languid folds on the figures’ bodies.

The Beau Dieu looks out onto visitors to the cathedral with an expression of peace, holding one hand in a gesture of blessing and a book in the other, signifying the importance of the biblical text. Originally, this figure and the rest of the portal sculpture would have been painted in dazzling colors, enhancing their lifelike qualities. Some of this polychromy remains along the hem of the Beau Dieu’s garment and in the outward gaze of the eyes.

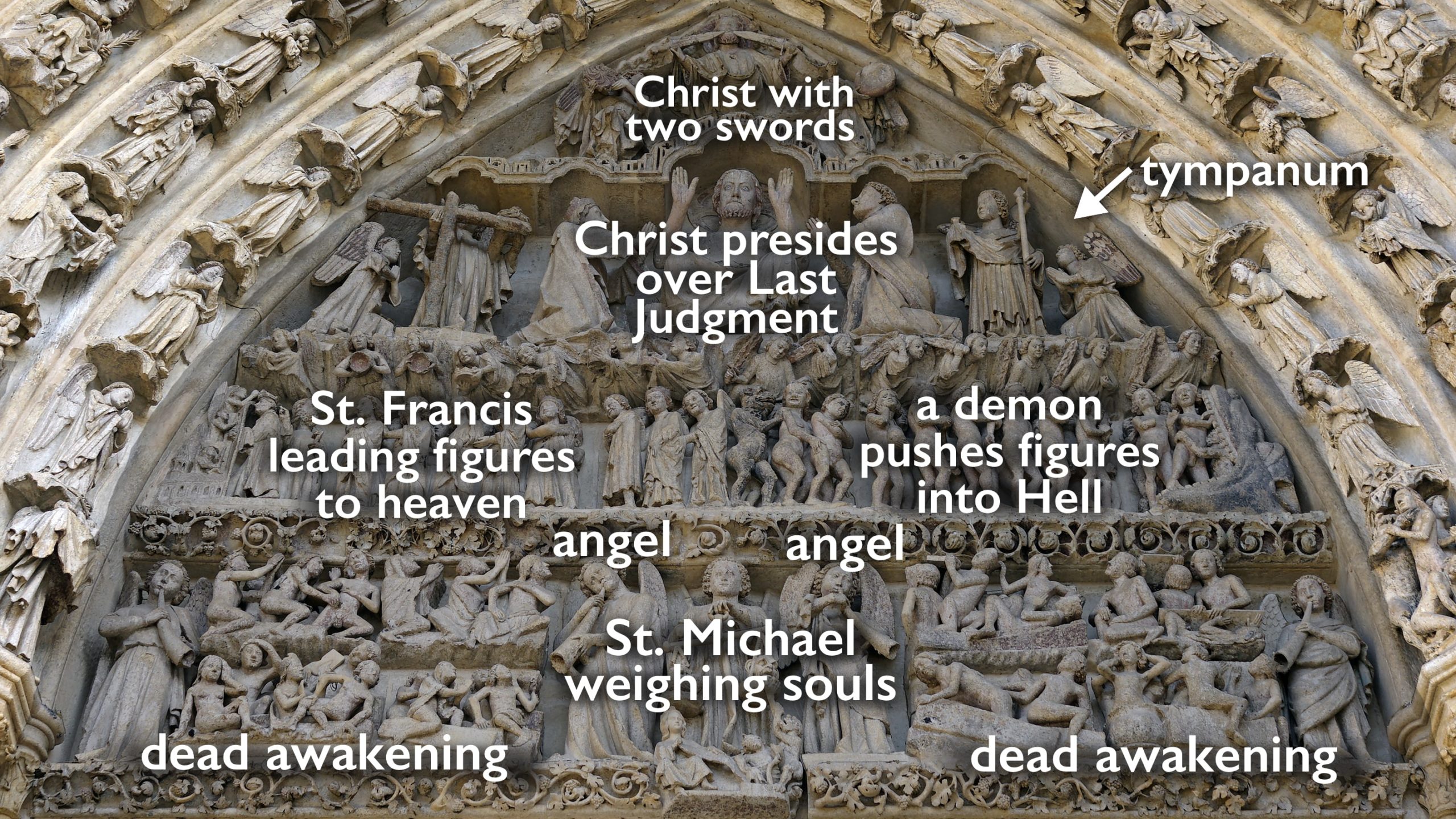

Above the trumeau, the tympanum depicts two more images of Christ. One version of Christ appears seated between kneeling figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. He presides over the Last Judgment, a biblical event described in the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, in which the dead are awakened and sorted into Heaven and Hell.

On the lowest register of the tympanum, we see figures awakening from their tombs while St. Michael, flanked by trumpeting angels, weighs the souls of the dead. Above this register on the left, St. Francis leads a line of figures clothed in long robes into Heaven, where they are welcomed by St. Peter. On the right side of this register, a demon pushes a line of terrified, naked figures into the jaws of Hell. At the very top of the tympanum, a third image of Christ flies above the whole scene with two swords coming out of his mouth, a representation of the Christ of the Apocalypse, described in the Book of Revelation:

Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. “He will rule them with an iron scepter.” He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: king of kings and lord of lords.Revelation 2:15

Courage (virtue) and fear (vice), west façade, Amiens Cathedral (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In addition to the three depictions of Christ, another set of images carved in relief appear at eye level: the Vices and Virtues. These quatrefoils are presented in pairs: Courage and Cowardice, Patience and Anger, Chastity and Lust.

The Virtues are represented by seated female figures holding shields, while narrative scenes depict the Vices. In the example illustrated here, the vice of cowardice is represented on the bottom as a knight so frightened by a small rabbit that he jumps away and drops his sword. Above, is the virtue of courage represented by a seated figure holding a shield with the image of a lion.

These images suggest to the viewer that they, too, can choose to follow a life of virtue, rather than a life of vice. By following this prescription, he or she can work towards an afterlife in the kingdom of Heaven, like St. Francis, and avoid the jaws of Hell.

When you enter the cathedral (the entrance is on the west side), you might notice that the interior space is organized into three main aisles: a tall central aisle, called the nave, flanked by narrower aisles on either side. The church is laid out in a Latin cross plan, with a transept that intersects the nave and defines the choir.

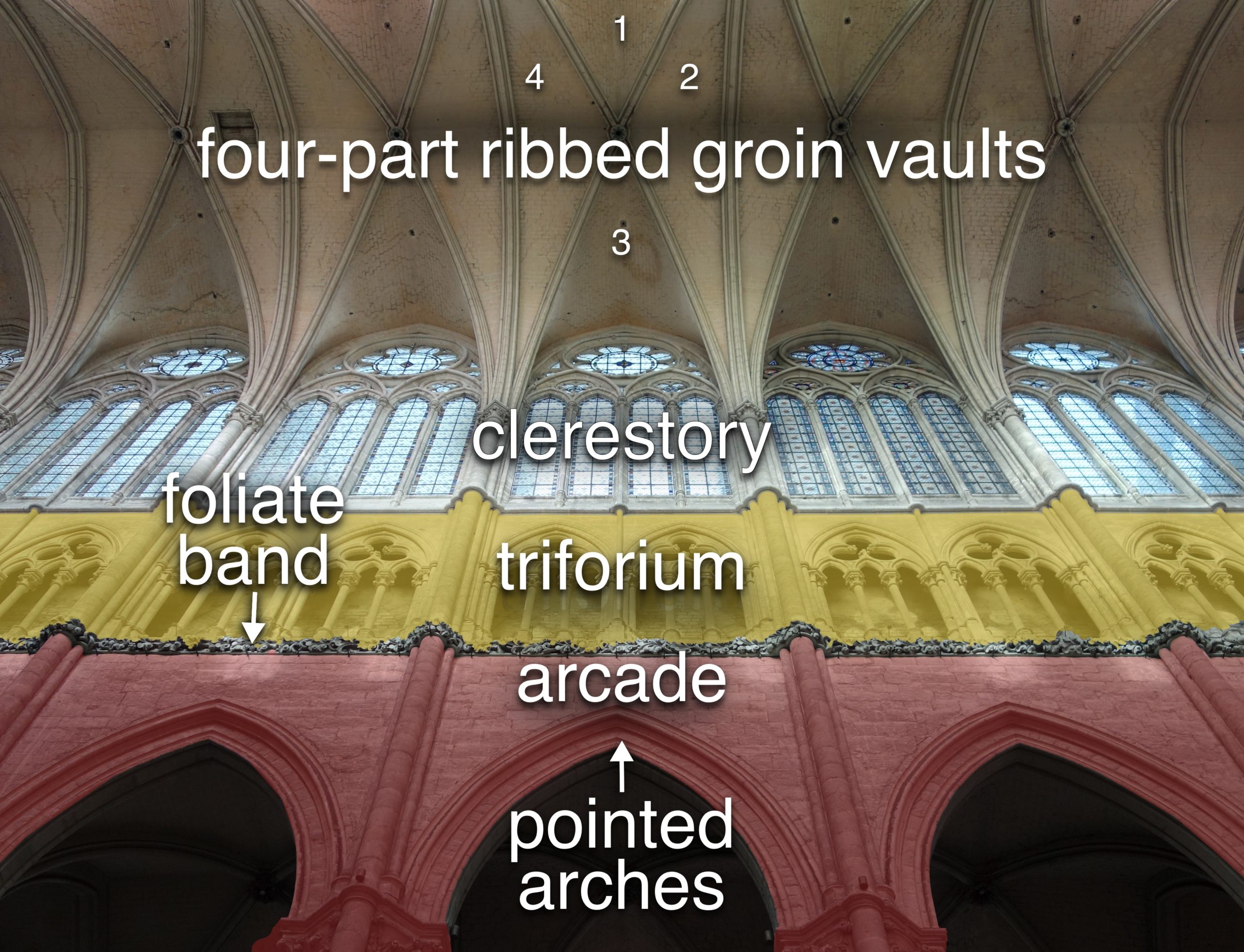

If you look up, you’ll see that the building is made up of three levels: the arcade, the triforium, and the clerestory of tall windows. The large piers that support the main arcade are over six feet in diameter, supporting a series of pointed arches crowned with quadripartite ribbed groin vaults.

Just below the triforium, you might notice the sculpted foliate band that runs the entire length of the cathedral. This feature is unique to Amiens; no other Gothic cathedral from this period has comparable foliate carving as elaborate or monumental in scale. The foliate band is made up of hundreds of individually sculpted blocks that fit together to create a seamless line of foliage—though if you look closely, you’ll see subtle differences throughout the building. The foliate carving in the nave is robust, while the transepts have less emphasis on the fleshy leaves. In the choir, the pattern changes altogether. The three modes of foliate carving correspond roughly to the three phases of construction carried out by three separate architects.

Clerestory in the nave (flying buttresses visible through the windows), Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Little remains of the original stained glass in the clerestory, which has been replaced with clear windows. Originally, light coming into the cathedral would have been filtered through the saturated jewel tones of colored glass. The medieval stained glass was removed before World War I as a precaution, but most of it was destroyed in a fire while in storage. The clear glass was installed later in the 20th century, incorporating fragments of medieval glass that survived. Some of the original panels can be seen in the choir triforium and rose windows.

Center of the Labyrinth, Amiens Cathedral, installed 1288. The original plaque is in the Musée de Picardie.

Amiens Cathedral is not only one of the most important examples of Gothic architecture from the medieval period, it is an experiential work of art signed by its makers. At the center of a large labyrinth, we find a plaque that depicts four men: the bishop Evrard de Foulloy, under whose leadership the cathedral’s construction began, and three architects: Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Thomas’s son, Renaud. It is unusual that we know the names of these medieval master masons, as few building records from this time survive. These architects directed the construction of the cathedral beginning in 1220 until the installation of the labyrinth pavement in 1288 (today’s pavement, a faithful replica of the original, was replaced in the 1880s). Even though work continued after 1288, much of what we see today is the creation of these architects and their teams of sculptors and stonecutters.

Glass behind the triforium in the choir, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

You can notice changes in the building’s design as you compare work in the nave and transepts with the architecture in the choir. The last architect, Renaud de Cormont, made some departures from his father’s design, including installing stained glass behind the triforium instead of opting for a solid wall, changing the decorative sculpture in the capitals, and altering the design of the foliate band.

Unfortunately, some of these changes also led to structural instability in this part of the building. Just before 1500, one of the vaults suffered a partial collapse. The building had to be reinforced by an iron chain (still hidden inside the triforium today), and additional flying buttresses on the exterior.

On the exterior of this part of the building, we also see a difference in the flying buttresses: whereas the flying buttresses in the nave are solid, Renaud chose to use lace-like patterns in the openwork flying buttresses in the choir.

Why did Renaud do this? Art historians don’t have a definitive answer, but it is possible that the architect was responding to trends in Gothic design opting for more light, thinner supports, and more decorative qualities. Whatever the intention, the aesthetic effect is one of extraordinary delicacy.

In the choir, the architecture appears to float, as if the vaults were suspended above with little to support them. The added stained glass in the triforium would have filled this important part of the building—where the canons performed the mass in front of the high altar—with an ethereal light of dazzling color.

Through its architecture, sculpture, and history, Amiens Cathedral provides a window into the practice and culture of religious belief of the Middle Ages, as well as the ingenuity of medieval architects, masons, and artisans. This building stands as an irreplaceable example of the many dynamic forces at work in Gothic architecture.

Amiens Cathedral (official website)

Life of a Cathedral: Notre-Dame of Amiens

Virtual Tour of Amiens Cathedral

Amiens Cathedral Construction Sequence

Source: Dr. Emogene Cataldo, “Amiens Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, March 18, 2021, accessed November 11, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/amiens/.

Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, 1248. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

URL: https://youtu.be/vigjJih8Pn4

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Sainte-Chapelle, Paris,” in Smarthistory, May 24, 2017, accessed November 11, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/sainte-chapelle-paris/.

URL: https://youtu.be/abKtscO6lMU

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Humanizing Mary: the Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux,” in Smarthistory, October 5, 2017, accessed November 11, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/virgin-jeanne-devreux/.

Casket with Scenes of Romances, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

A knight crawls across a sword-shaped bridge while he is pelted with swords and arrows. A maiden cradles a unicorn’s head in her lap while a hunter pierces the unicorn from behind with a spear. Knights attempt to invade a castle yet are pelted with flowers by the castle’s female inhabitants. A man spies on two lovers from his hiding place within a tree.

What do these scenes have in common? They are just a few examples of the images that adorn a lavish ivory box created in late medieval France.

Details, Casket with Scenes of Romances, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

Just as today’s pop culture can be found repeated across a wide variety of visual formats—movies, comic books, clothing, and memes, to name a few—so it was in the Middle Ages. Popular romances such as the legends of King Arthur and the Romance of the Rose were retold in a plethora of visual adaptations: illuminated manuscripts, textiles, architectural ornament, and small-scale sculpture, such as the ivory box currently at the Walters Art Museum whose imagery is described above.

Another casket with scenes from romances, c. 1310–30, French, ivory, 10.9 x 25.3 x 15.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The ivory box discussed in detail here is one of eight surviving ivory composite caskets. It is composite because the scenes that are carved into relief on its sides and lid hail from a variety of medieval stories and traditions. It is a casket, coming from the French term “coffret,” which translated means casket, but more generally means box; here, it has no connection to death. Far from being a macabre object, such ivory boxes are thought to have played a material role in medieval courtship, possibly given as a gift from one lover to another as a token of his or her affection. About the size of a modern-day jewelry box, these caskets could have held valued trinkets, such as love letters, jewelry, locks of hair, or other small objects of personal significance.

Casket with Scenes of Romances, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

That this ivory casket is one of eight with near identical imagery suggests several ideas to art historians. First, the eight caskets were produced in the same time period and place, likely Paris, a major center of ivory production in fourteenth-century France. As an artistic material, ivory was valuable and highly sought after. Imported during the later Middle Ages from eastern Africa, ivory was used by skilled artisans to render a variety of small scale sculptures, from boxes and statuettes to mirror cases and combs. The close similarities in the subject and style of the caskets’ imagery may point to their creation within a single medieval workshop, or among a group of artisans who were influenced by each other’s work. In addition, the repetition of these scenes of daring deeds and romantic love across the eight caskets suggests that such imagery was popular among a courtly medieval audience.

Late medieval household inventories are evidence that carved ivories were owned by members of nobility and royalty, such as Jean, the Duke of Berry and Clémence of Hungary, Queen of France. Such socially elevated, and therefore educated, patrons would certainly have been aware of and able to “read” the multivalent and playful imagery carved into the caskets, thanks to their familiarity with both the literary texts and oral traditions of the romance genre.

Furthermore, whereas today we distinguish between the sacred and the secular, or the religious and the irreligious (think of the separation between Church and State), this was not the case in the Middle Ages. On the contrary, medieval images of Christian devotion could be found alongside images of mortal life, such as romantic love. This intertwining of Christianity and romance underpins the imagery found on the eight composite ivory caskets.

Casket Lid, “Siege of the Castle of Love” and a jousting tournament. Casket with Scenes of Romances, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

The Walters Art Museum casket’s lid is decorated with a very busy scene divided into two parts. The metal fastenings that hold the casket together also divide the lid into sections, allowing for it to be read similar to cartoon panels. On each end of the lid, an image known as the “Siege of the Castle of Love” is depicted. Knights armed with a variety of weapons—bows and arrows, and a trebuchet—attempt to gain access to a castle inhabited solely by women. The women respond playfully, fending off the knights’ advances, but with flowers as ammunition!

Although art historians are unsure of the origin of this image, it is also found within illuminated manuscripts (such as the Luttrell Psalter), suggesting that it was a well-known theme during the later Middle Ages. The lid’s two center panels continue the theme of combat, depicting two knights jousting, observed by a balcony full of maidens. Both scenes focus on male combat and female acquiescence and observation, suggesting that the scenes were intended to serve as an allegory of romantic courtship.

Casket left-end panel depicting Tristan and Isolde’s tryst and the death of a unicorn, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

Moving from the lid to the left-end panel, the theme of romantic courtship is continued, although here it is juxtaposed with an image of Christian significance. On the left side of the panel, forbidden lovers Tristan and Isolde (from the legends of King Arthur) meet for a secret rendezvous. They are foiled, however, by Tristan’s uncle, King Mark, who spies on them from between the branches of the tree. Luckily, Tristan and Isolde see King Mark’s reflection in a pool of water, and so pretend to be “just friends.”

The Unicorn in Captivity (one of seven woven hangings popularly known as the Unicorn Tapestries or the Hunt of the Unicorn), 1495–1505, wool, silk, silver, and gilt (The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

To the right of this scene of unrequited love, a more violent episode occurs. A maiden holds a chaplet in her right hand. With her left hand, she cradles the head of a unicorn. Unfortunately for the unicorn, a hunter has snuck up behind him, and has pierced him through with a spear. It may seem strange to us, as contemporary viewers, that for a medieval viewer, this violent image of the capture of a mythical creature was symbolic of love. However, such was the case. Indeed, the unicorn as a symbol of love appears in a variety of other medieval artistic contexts, such as the late fifteenth-century unicorn tapestry, now at the Met Cloisters, in which the unicorn is similarly depicted as captive, and serves as a visual metaphor of marriage and fertility.

In the Middle Ages, the unicorn was viewed as a semi-mythical and incredibly shy creature. It was said that the only way to catch a unicorn was to bait it with a virgin girl, symbolic of the dangers of feminine wiles. The unicorn was simultaneously viewed as a symbol of Christ, who was sometimes referred to as a “spiritual unicorn,” because he allowed himself to be killed on account of his love for humanity. Read as one, the killing of the defenseless unicorn, paired with its Christian interpretation, results in this image’s complex meaning—symbolic of both Christ’s sacrifice as well as the perils of feminine seduction in the pursuit of romantic love.

Taken together, the scenes of Tristan and Isolde’s romantic tryst and the death of the unicorn present to viewers two opposing versions of love. Whereas Tristan and Isolde exemplify romantic, physical, and forbidden love, the unicorn represents a Christian’s pure love for Christ as Savior, a love meant to last beyond the mortal world.

Casket with Scenes of Romances, c. 1330–50, ivory, modern iron mounts, France, 11.8 x 25.2 x 12.9 cm (The Walters)

Moving to the rear panel of the Walters casket, we come to a further four images from the legends of King Arthur. Like on the casket’s lid, metal fastenings act to divide the rear panel’s imagery into four distinct sections. From left, the first, third, and fourth sections depict the adventures of the gallant Sir Gawain, a true ladies’ man. Neither vicious lion nor hailstorm of swords and arrows will prevent Sir Gawain from rescuing the maidens of the Marvelous Castle, who are depicted in the rightmost section. Meanwhile, in the second from left panel, Sir Lancelot crawls across the infamous Sword Bridge. Like Gawain, he is pelted with weaponry, and the water beneath the bridge churns ominously. Also like Gawain, Lancelot’s chivalrous efforts are for the benefit of a woman—his (forbidden) lover Queen Guinevere, the wife of Lancelot’s friend and lord, King Arthur. These four scenes of knightly daring thus have a more obvious message than the unicorn on the left-end panel. Love, at least in medieval legends, often comes at the price of a grand gesture.

Perhaps for a medieval man or woman, that grand gesture could have been the presentation of this luxury ivory casket to a special someone. The ivory casket would have been an intimate gift— both in terms of its small size, and the close observation required to understand the images. In this way, for their medieval viewers, ivory composite caskets could function as visual surveys of the genre of love, translating into image popular ideas of courtship, chivalry, and romantic and Christian love.

Additional resources:

Middle left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

And the angel thrust in his sharp sickle into the earth, and gathered the vineyard of the earth, and cast it into the great press of the wrath of God (Douay-Rheims translation)

Upper left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

The illustration is a visual interpretation of this text, with some extra details added. A figure on the right harvests grapes from the vines on the right and Christ, with his cruciform (cross-shaped) halo, pours the grapes from the basket on his back into the winepress. God and his angels bless the scene from above.

Left: Commentary (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v); right: Middle left (detail), Scenes from the Apocalypse, Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, France, c. 1225–45 (The British Library, Harley MS 1527 fol. 140v)

And I saw another sign in heaven, great and wonderful: seven angels having the seven last plagues. For in them is filled up the wrath of God.(Douay-Rheims translation)

Top: Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France; and below: Author Dictating to a Scribe, Bible of Saint Louis (Moralized Bible), France, probably Paris, c. 1227–34, 14 3/4 x 10 1/4 inches / 37.5 x 26.2 cm (The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.240, fol. 8)

In 1226 a French king died, leaving his queen to rule his kingdom until their son came of age. The 38-year-old widow, Blanche of Castile, had her work cut out for her. Rebelling barons were eager to win back lands that her husband’s father had seized from them. They rallied troops against her, defamed her character, and even accused her of adultery and murder.

Caught in a perilous web of treachery, insurrections, and open warfare, Blanche persuaded, cajoled, negotiated, and fought would-be enemies after her husband, King Louis VIII, died of dysentery after only a three-year reign. When their son Louis IX took the helm in 1234, he inherited a kingdom that was, for a time anyway, at peace.

Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France (detail), Dedication Page with Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France, Bible of Saint Louis (Moralized Bible), c. 1227–34, ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum (The Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 240, fol. 8).

A dazzling illumination in New York’s Morgan Library could well depict Blanche of Castile and her son Louis, a beardless youth crowned king. A cleric and a scribe are depicted underneath them (see image at the top of the page). Each figure is set against a ground of burnished gold, seated beneath a trefoil arch. Stylized and colorful buildings dance above their heads, suggesting a sophisticated, urban setting—perhaps Paris, the capital city of the Capetian kingdom (the Capetians were one of the oldest royal families in France) and home to a renowned school of theology.

This last page the New York Morgan Library’s manuscript MS M 240 is the last quire (folded page) of a three-volume moralized bible, the majority of which is housed at the Cathedral Treasury in Toledo, Spain. Moralized bibles, made expressely for the French royal house, include lavishly illustrated abbreviated passages from the Old and New Testaments. Explanatory texts that allude to historical events and tales accompany these literary and visual readings, which—woven together—convey a moral.

Assuming historians are correct in identifying the two rulers, we are looking at the four people intensely involved in the production of this manuscript. As patron and ruler, Queen Blanche of Castile would have financed its production. As ruler-to-be, Louis IX’s job was to take its lessons to heart along with those from the other biblical and ancient texts that his tutors read with him.

In the upper register, an enthroned king and queen wear the traditional medieval open crown topped with fleur-de-lys—a stylized iris or lily symbolizing a French monarch’s religious, political, and dynastic right to rule. The blue-eyed queen, left, is veiled in a white widow’s wimple. An ermine-lined blue mantle drapes over her shoulders. Her pink T-shaped tunic spills over a thin blue edge of paint which visually supports these enthroned figures. A slender green column divides the queen’s space from that of her son, King Louis IX, to whom she deliberately gestures across the page, raising her left hand in his direction. Her pose and animated facial expression suggest that she is dedicating this manuscript, with its lessons and morals, to the young king.

Louis IX, wearing an open crown atop his head, returns his mother’s glance. In his right hand he holds a scepter, indicating his kingly status. It is topped by the characteristic fleur-de-lys on which, curiously, a small bird sits. A four-pedaled brooch, dominated by a large square of sapphire blue in the center, secures a pink mantle lined with green that rests on his boyish shoulders.

In his left hand, between his forefinger and thumb, Louis holds a small golden ball or disc. During the mass that followed coronations, French kings and queens would traditionally give the presiding bishop of Reims 13 gold coins (all French kings were crowned in this northern French cathedral town.) This could reference Louis’ 1226 coronation, just three weeks after his father’s death, suggesting a probable date for this bible’s commission. A manuscript this lavish, however, would have taken eight to ten years to complete—perfect timing, because in 1235, the 21-year-old Louis was ready to assume the rule of his Capetian kingdom from his mother.

Coronation of the Virgin, tympanum of central portal, north transept, Chartres Cathedral, c. 1204–10 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Queen Blanche and her son, the young king, echo a gesture and pose that would have been familiar to many Christians: the Virgin Mary and Christ enthroned side-by-side as celestial rulers of heaven, found in the numerous Coronations of the Virgin carved in ivory, wood, and stone. This scene was especially prevalent in tympana, the top sculpted semi-circle over cathedral portals found throughout France. On beholding the Morgan illumination, viewers would have immediately made the connection between this earthly Queen Blanche and her son, anointed by God with the divine right to rule, and that of Mary, Queen of heaven and her son, divine figures who offer salvation.

Cleric (detail), Dedication Page with Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France, Bible of Saint Louis (Moralized Bible), c. 1227–34, ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum (The Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 240, fol. 8).

The illumination’s bottom register depicts a tonsured cleric (churchman with a partly shaved head), left, and an illuminator, right.

The cleric wears a sleeveless cloak appropriate for divine services—this is an educated man—and emphasizes his role as a scholar. He tilts his head forward and points his right forefinger at the artist across from him, as though giving instructions. No clues are given as to this cleric’s religious order, as he probably represents the many Parisian theologians responsible for the manuscript’s visual and literary content—all of whom were undoubtedly told to spare no expense.

Scribe (detail), Dedication Page with Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France, Bible of Saint Louis (Moralized Bible), c. 1227–34, ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum (The Morgan Library and Museum, MS M. 240, fol. 8).

On the right, the artist, donning a blue surcoat and wearing a cap, is seated on cushioned bench.

Knife in his left hand and stylus in his right, he looks down at his work: four vertically-stacked circles in a left column, with part of a fifth visible on the right. We know, from the 4887 medallions that precede this illumination, what’s next on this artist’s agenda: he will apply a thin sheet of gold leaf onto the background, and then paint the medallion’s biblical and explanatory scenes in brilliant hues of lapis lazuli, green, red, yellow, grey, orange and sepia.

Blanche undoubtedly hand-picked the theologians whose job it was to establish this manuscript’s guidelines, select biblical passages, write explanations, hire copyists, and oversee the images that the artists should paint. Art and text, mutually dependent, spelled out advice that its readers, Louis IX and perhaps his siblings, could practice in their enlightened rule. The nobles, church officials, and perhaps even common folk who viewed this page could be reassured that their ruler had been well trained to deal with whatever calamities came his way.

This 13th century illumination, both dazzling and edifying, represents the cutting edge of lavishness in a society that embraced conspicuous consumption. As a pedagogical tool, perhaps it played no small part in helping Louis IX achieve the status of sainthood, awarded by Pope Bonifiace VIII 27 years after the king’s death. This and other images in the bible moralisée explain why Parisian illuminators monopolized manuscript production at this time. Look again at the work. Who else could compete against such a resounding image of character and grace?

Additional resources:

This page at The Morgan Library and Museum

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion, folio 331r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

Deluxe medieval devotional books used images and texts together to produce compelling, spiritual experiences for their readers. One particularly dramatic image confronts the reader from the pages of a book made for a woman, Bonne of Luxembourg, in the French royal family. In the center of the parchment page, on a blue field teeming with scrolling golden vines, the instruments used to torture Christ during the Passion stand arranged for the viewer’s inspection.

In the center, filling the composition from top to bottom, is a gaping, disembodied wound. Framed with an almond-shaped ring of white flesh, the bright orange-red tones of torn flesh deepen in color closer to the irregular, vertical brown gash in the center. This is the spear wound created in Christ’s side after his death on the cross, isolated for the pious reader’s contemplation. Shown at what medieval Christians believed to be actual size (about 2 inches), the wound dominates the composition while the miniature instruments of torture that surround it seem to fade into the background. Along with the text (a prayer describing Christ’s suffering), and the manuscript’s lively margins, this graphic painting worked to engage viewers in emotional contemplation of Jesus’ sacrifice.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion, detail, folio 331r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

In the Middle Ages, this powerful image was meant to orient pious readers’ attention to Christ’s body and the physical suffering he endured to ensure their salvation. This emphasis on Christ’s body is part of a larger trend in late medieval devotion known as affective piety, in which compassion for Christ’s suffering held the key to salvation. With its almond shape, vertical orientation, and confrontational placement, the wound of Christ in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg might remind a modern viewer of the Eye of Sauron (known from J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings). Medieval viewers likely overlaid other associations onto such images of Christ’s wound. The change in the wound’s orientation from a diagonal slit to a vertical opening and the isolation of the wound as an almond-shaped device transform it into an image strongly reminiscent of medieval representations of the vulva and the vaginal opening. Similar imagery persists in modern visual culture, such as Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation The Dinner Party. This association of Christ’s side wound with female reproductive organs has connections with mystical writings that eroticized the body of Christ and that emphasized its nurturing and generative qualities.

Although we often think of paintings today as freestanding, portable objects, paintings in medieval books were not meant to be isolated from their manuscript context. When closed, Bonne’s prayer book measures just over five inches high—smaller than an adult’s hand. This small size distinguishes personal prayer books from books sized for display, like the Winchester Bible. Deluxe prayer books like Bonne’s were status symbols, but they were also intimate, personal objects that facilitated direct communication with God.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, miniature of the Crucifixion with Christ displaying his side wound to Bonne of Luxembourg and John, Duke of Normandy, folio 328r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

The image of Christ’s side wound is one of fifteen miniatures distributed among the 334 folios of the prayer book. Each miniature introduces and illustrates the themes of the manuscript’s most important texts. The miniature of the wound comes in the midst of the final text, focusing on Christ’s experience on the cross.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, miniature of the Crucifixion with Christ displaying his side wound to Bonne of Luxembourg and John, Duke of Normandy, detail, folio 328r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

This text opens with a miniature of the crucified Christ showing his side wound to two kneeling figures: Bonne and her husband, the future French king John the Good. Viewed in sequence, the miniature with the crucified Christ instructed Bonne (personally!) where to focus her devotional attentions, while the miniature of the wound three folios later provided her direct, visual access to it. The wound provides a dramatic climax to the prayer and the book.

Devotion to Christ’s side wound emerges from late medieval Christian mysticism, writings by monastic men and especially women articulating their personal, visionary, and ecstatic experiences of the divine. In mystical writings, Christ’s body often takes on feminine qualities, becoming permeable, generative, and nourishing. Catherine of Siena’s biography records a vision in which Christ nourishes the mystic from his side wound, an encounter that is simultaneously maternal and erotic:

With that, he tenderly placed his right hand on her neck, and drew her towards the wound in his side. ‘Drink, daughter, from my side,’ he said, ‘and by that draught your soul shall become enraptured with such delight that your very body, which for my sake you have denied, shall be inundated with its overflowing goodness.’ Drawn close in this way, … she fastened her lips upon that sacred wound, … and there she slaked her thirst.[1]

Images of the side wound and the mystical tradition from which they emerge have provided fertile material for scholars engaged in “queering” the Middle Ages. Queering means questioning assumptions of heterosexual and cisgender normativity in the past, providing a critique of modern scholarship in the process.

The image of the side wound, like Catherine’s vision, grants feminine bodily attributes to Christ, destabilizing assumptions about his gender. In mystical images and texts, Christ’s capacity to transcend the gender binary, like his capacity to transcend the binary of life and death, underscores his divinity. Christ is not the only figure within medieval culture to transgress the gender binary. Medieval literature—religious and secular alike—is replete with transgender figures, from saints like Marinos the Monk and, perhaps, Joan of Arc, to the fictional protagonists of the thirteenth-century romances Silence and Yde et Olive.

While the voices of actual marginalized people are rarely recorded in medieval documents, Eleanor Rykener is a striking exception. Arrested in late fourteenth-century London for sexual misconduct, and named in court records as John, she identified herself as Eleanor in her testimony. While the gender-ambiguous Christ is a social construction, it can nevertheless call our attention to individuals and groups hidden within or excluded from the historical record and give modern students a means to consider their positions and experiences within their time.

The Fauvel Master, miniature of the Crucifixion, the wound of Christ, and the instruments of the passion, detail, folio 140v, in L’Image du monde of Gossouin of Metz, c. 1320-1325 (Bibliothèque nationale de France ms. fr. 574)

Echoing the eroticism of Catherine’s vision, medieval readers’ interactions with their devotional books could be very intimate, including the touching or kissing of images, and other images of the wound of Christ show paint loss from readers’ pious stroking of the paint. Such devotion to Christ’s side wound further destabilizes presumptions of heterosexuality in medieval and much modern thought. With its focus on touch and penetration, the devotion of men and women alike to Christ’s side wound had the capacity for queer connotations. The ragged, parted lips of Christ’s wound carried many meanings for their medieval viewers, from the pleasures of being enveloped in divine love to protections in childbirth.

Limbourg Brothers, January, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1413-16, ink on vellum (Musée Condé, Chantilly, fol. 1v)

Bonne, who was married at seventeen to the French royal heir and bore nine children before her death of plague at age 34, may have found these associations with pregnancy particularly meaningful. However, the reproductive and the erotic resonances of the image are not mutually exclusive, and, regardless of Bonne’s sexuality, we can see in this imagery a potential model for same-sex desire in the Middle Ages. Such models are crucial for the study of sexualities in a period when homosexual relationships, especially between women, were rarely acknowledged in mainstream texts or conversations. When references to homosexuality do appear in medieval art, it is often framed as a sin, as in the representations of “sodomy” in moralized bibles. Still, more subtle, positive references to homosexual identities may be found. Medieval gossip about Bonne’s son, Jean, Duke of Berry, implies that he may have been attracted to men. Art historian Michael Camille has suggested that Paul de Limbourg devised several well-dressed young men in the feasting miniature of the Très Riches Heures for the duke’s pleasure.

The images and texts of Bonne of Luxembourg’s prayer book contained many layered messages for its royal reader. While the content of images and texts alike would have been planned by a devotional adviser, the paintings are attributed to Parisian illuminator Jean le Noir and his workshop, which by 1358 included his daughter, Bourgot, in a prominent role. The commercial book shops of the late Middle Ages were collaborative, often family enterprises, with men and women of different generations working side-by-side. Three artists’ hands have been identified within the manuscript, though it is not possible to know which belonged to Jean, Bourgot, or other workshop members.

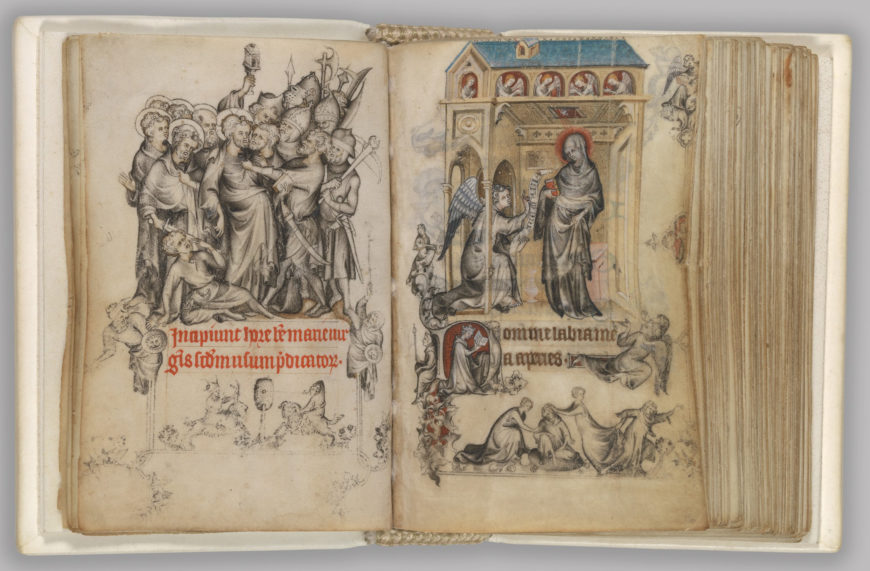

Jean Pucelle, opening pages showing the Arrest of Christ, the Annunciation, Queen Jeanne d’Evreux in prayer, and erotic games in the margins, fols. 15v–16r, in the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, c. 1324-1328 (The Cloisters Collection)

Jean le Noir’s workshop specialized in the grisaille style of painting first popularized among the royal patrons of France during the previous generation by illuminator Jean Pucelle. The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg looks back both in style and in content to the miniature prayer book Pucelle made for an earlier queen of France, Jeanne d’Évreux, between about 1324 and 1328.

While the imagery of Bonne’s prayer book brought her into intimate contact with God, its style connected her with the royal French line. These connections were carried forward by Bonne’s children, particularly Jean de Berry, who around 1371 commissioned a prayer book with the same Passion texts as his mother’s from the now elderly Jean le Noir. These stylistic, thematic, and textual traditions across generations speak to the complex dynamics of transgression and normativity within medieval manuscript patronage at the highest levels.

Read more about Private Devotion in Medieval Christianity on the Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline

Construction of the current church building was begun circa 1108, and was essentially completed around 50 years later. The basic layout for churches at that time was the shape of a cross, with the east end as the top, the transepts making the crossing arm, and the nave as the longer extension at the bottom of the cross. The east end held the altar and choir, or quire, which were used by the clergy during daily masses. The nave was accessible to the lay community. Although medieval British churches are basically oriented east to west, they all vary slightly. When a new church was to be built, the patron saint was selected and the altar location laid out. On the saint’s day, a line would be surveyed from the position of the rising sun through the altar site and extending in a westerly direction. This was the orientation of the new building.

In clerical terms, Southwell Minster is a cathedral; but rather than rummage in ecclesiastical definitions, this essay will look at the architectural styles.

Interior order

On entering Southwell Minster, the sense of space feels logical and follows a well-defined and rhythmic order. The nave is in the Norman, or Romanesque, architectural style. It is delineated by simple rounded – Roman – stone arches springing from heavy round stone columns. The arcade on each side separates the nave from the side aisles, which allow people to move through the church to smaller side chapels. Above the first tier is a second arcade with smaller arches defining the gallery, and above that is another arcade – smaller still – which includes windows and is known as the clerestory. The ceiling of Southwell Minster is a wooden barrel vault.

The arches, column capitals, window surrounds, and portals are decorated with carved patterns that are geometric and straightforward. Although the material is stone, its lack of detailed texture gives it a plastic quality, especially when seen in some lights. The stone, Permian sandstone, has a warm cream color, while the heavy arches and massive walls impart a feeling of strength and permanence. This commanding style represented effective propaganda for William the Conqueror, who had invaded Britain in 1066 and imposed strong organizational systems in both the Church and government.

From Norman to Gothic

The transepts are also in the Norman style, severe and blunt. But as you move further east and enter the quire, the uncomplicated architecture and decoration gives way to pointed arches and curlicue embellishments. The sense of moving to a different building and place are somewhat confusing at first, until you are fully inside the east end and find yourself enveloped in the Gothic style.

The original east end of Southwell, and of many other medieval cathedrals, was found to be too small once the building was completed, so the old east end was pulled down and replaced with a larger extension in the latest fashion. Although the new east end was built within roughly one hundred years of the original building, architecture had moved on quickly. Now the arches were pointed at the top, and the decoration was more and more ornate. Structurally, new techniques allowed for larger windows than were possible in the Romanesque idiom.

Prebendary seats of stone

The Chapter House, begun circa 1300, is accessible from the north transept, and was the meeting hall of the original prebends (a clergy member drawing a stipend from Anglican church revenues) associated with the minster. Each prebend, who would have held certain responsibilities for his area of the diocese, had a stone seat on the wall of the chapter house. Each seat alcove is topped with decorated trefoil arches and a variety of leaves. The “Leaves of Southwell” have been documented as some of the best medieval stone carvings in England, and represent oak, ivy, hawthorn, grape, hops, and other flora.

Because the Southwell Chapter House is relatively small, it does not require a center column to support the roof as a larger area would. The octagonal room is topped by a vault carried not only on ribs that reach to the center, but also on cross ribs that span between the main ribs. These intermediate ribs are known as tiercerons, and signify a further development into the more complex and decorated vaults that are an integral part of the English Decorated and Perpendicular Gothic styles.

As a whole or in its individual parts, Southwell Minster is a brilliant example of medieval architecture in England and its rapid development over 200 years. The building has suffered relatively little damage or major alteration over its thousand-year life. Indeed, part of its appeal is its architectural integrity, as well as the fact that it is a living (i.e., still in use) building.

As the years have passed, new decoration has been added that reflects a functioning parish community – a baptismal font from 1661, stained glass windows from various centuries, a modern sculpture of Christus Rex from the twentieth century. The church is not overrun with tourists, but is still very much a local parish with an active congregation that continues to use the building, ring the bells, and weave the ties of history into twenty-first century life.

Cathedrals of Britain from the BBC

URL: https://youtu.be/H4zXQrBeJU8

There are so many superlatives consorting with the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Salisbury: it has the tallest spire in Britain (404 feet); it houses the best preserved of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta (1215); it has the oldest working clock in Europe (1386); it has the largest cathedral cloisters and cathedral close (grounds) in Britain; the choir (or quire) stalls are the largest and earliest complete set in Britain; the vault is the highest in Britain. Bigger, better, best—and built in a mere 38 years, roughly from 1220 to 1258, which is a pretty short construction schedule for a large stone building made without motorized equipment.

One factor that enabled Salisbury Cathedral to become so extraordinary is that it was the first major cathedral to be built on an unobstructed site. The architect and clerics were able to conceive a design and lay it out exactly as they wanted. Construction was carried out in one campaign, giving the complex a cohesive motif and singular identity. The cloisters were started as a purely decorative feature only five years after the cathedral building was completed, with shapes, patterns, and materials that copy those of the cathedral interior.

Looking west from the choir to the nave, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Nave elevation, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

It was an ideal opportunity in the development of Early English Gothic architecture, and Salisbury Cathedral made full use of the new techniques of this emerging style. Pointed arches and lancet shapes are everywhere, from the prominent west windows to the painted arches of the east end. The narrow piers of the cathedral were made of cut stone rather than rubble-filled drums, as in earlier buildings, which changed the method of distributing the structure’s weight and allowed for more light in the interior.

The piers are decorated with slender columns of dark gray Purbeck marble, which reappear in clusters and as stand-alone supports in the arches of the gallery, clerestory, and cloisters. The gallery and cloisters repeat the same patterns of plate tracery—basically stone cut-out shapes—of quatrefoils, cinquefoils, even hexafoils and octofoils. Proportions are uniform throughout.

One deviation from the typical Gothic style is the way the lower arcade level of the nave is cut off by a string course that runs between it and the gallery. In most churches of this period, the columns or piers stretch upwards in one form or another all the way to the ceiling or vault (see diagram below). Here at Salisbury the arcade is merely an arcade, and the effect is more like a layer cake with the upper tiers sitting on top of rather than extending from the lower level.

Comparison of the nave elevations of Salisbury Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral Nave elevation, photos: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The original design called for a fairly ordinary square crossing tower of modest height. But in the early part of the 14th century, two stories were added to the tower, and then the pointed spire was added in 1330. The spire is the most readily identified feature of the cathedral and is visible for miles. However, the addition of this landmark tower and spire added over 6,000 tons of weight to the supporting structure. Because the building had not been engineered to carry the extra weight, additional buttressing was required internally and externally. The transepts now sport masonry girders, or strainer arches, to support the weight. Not surprisingly, the spire has never been straight and now tilts to the southeast by about 27 inches.

Scissor (strainer) arches in the east transept, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Over the centuries the cathedral has been subject to well-intentioned, but heavy-handed restorations by later architects such as James Wyatt and Sir George Gilbert Scott, who tried to conform the building to contemporary tastes. Therefore, the interior has lost some of its original decoration and furnishings, including stained glass and small chapels, and new things have been added. This is pretty typical, though, of a building that is several centuries old. Fortunately, the regularity and clean lines of the cathedral have not been tampered with. It is still refined, polished, and generally easy on the eye.

Purbeck colonettes at the crossing (transept), and to the left, gallery and clerestory moldings that have been repainted, Salisbury Cathedral, Salisbury, England, begun 1220, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Although it inspires the usual awe felt in such a grand and substantial building, and is as pretty as a wedding cake, it has had some criticism from art historians: Nikolaus Pevsner and Harry Batsford both disliked the west front, with its encrustation of statues and “variegated pettiness” (Batsford). John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic and writer, found the building “profound and gloomy.” Indeed, in gray weather, the monochromatic scheme of Chilmark stone and Purbeck marble is just gray upon gray.

The pictures, however, show the widely changing character of the neutral tones; sunlight transforms the building, and the visitor’s experience of it. This very quality is what made the Gothic style so revolutionary—the ability to get sunlight into a large building with massive stone walls. Windows are everywhere, and when the light streams through the clerestory arches and the enormous west window, the interior turns from drear gray to transcendent gold.

The Cathedral of Britain from the BBC

History of Salisbury Cathedral

Salisbury Cathedral Stained Glass

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows (Smarthistory essay)

Source: Valerie Spanswick, Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Salisbury Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed November 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/salisbury-cathedral/.

Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln, begun 1088, Lincoln, England URL: https://youtu.be/TuA00wpXaYA

Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Lincoln Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, July 19, 2017, accessed November 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/lincoln-cathedral/.

Wells Cathedral, Wells, England, begun c. 1175. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. URL: https://youtu.be/Hc96IQmEOIY

Gothic architecture from the V&A

Source: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Wells Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, July 18, 2017, accessed November 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/wells-cathedral/.

Gloucester Cathedral, begun 1089; speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker URL: https://youtu.be/uerlXNVwmW0

Additional resources

Gloucester Cathedral’s website

360 tour of the cathedral

Ely Cathedral, like nearly all medieval English cathedrals, saw many different phases of construction. Major building projects in the Middle Ages were both expensive and time-consuming, so renovations and additions were made piecemeal rather than all at once.The long period of time means that by looking at Ely, we can get a sense of each of the most important medieval English architectural styles, all in one building: Romanesque (in the nave), Early English (in the presbytery), Decorated (in the tower and Lady Chapel), and Perpendicular (in the eastern chantry chapels). See the plan below.

View of Ely Cathedral looking east from the Galilee to the Lady Chapel along the north side of the structure, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Ely Cathedral, sometimes referred to as “the ship of the Fens,” is a massive building rising up from the flat, marshy fenland of East Anglia. It isvisible from many miles away like a lone ship on a calm sea. Ely’s history began in the seventh century, when an Anglo-Saxon princess named Æthelthryth, or Etheldreda, made a holy vow of virginity. When she was married for political reasons, she fled her husband and founded a nunnery on the Isle of Ely. In Etheldreda’s time, Ely was an island surrounded by marshes (drained later, in the seventeenth century), and the place takes its name from the eels that dwelled in these swampy waters.

Inscribed paving stone marking the original tomb of Saint Etheldreda, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Etheldreda died just seven years after founding her nunnery. When her body was translated (ceremonially moved), from its original location fourteen years later, it was found to be incorrupt and it was put into a “new” sarcophagus—actually a reused one from an old Roman settlement nearby. A cult developed around Etheldreda, who became a saint (the common name for Etheldreda is St. Audrey).

Etheldreda’s nunnery was raided by Danish invaders in 870. Whether the relics of Etheldreda survived the raid is an open question, but the author of the twelfth-century text, the Liber Eliensis (Book of Ely), detailed stories of the continued power of Etheldreda’s relics, possibly intended to suggest that they had not been destroyed. Relics were very important objects in the Middle Ages, lending prestige to the churches where they were held, and drawing pilgrims, who would come seeking miracles. The existence of Etheldreda’s relics was therefore very important for the identity of the church at Ely, where in 970, with royal patronage, the church was refounded as a Benedictine monastery.

Though it had been the site of Christian worship for hundreds of years prior to 1082, little is known about the architecture of Ely before this date, when the first Norman abbot of Ely initiated the construction of a new church for the monastery. The foundations were laid out by a man in his 80s named Abbot Simeon who had previously been prior of the important monastic community of Winchester (in the south of England), where his brother, Walchelin, was bishop. Simeon and his brother had orchestrated a building campaign in Winchester that was still underway when Simeon came to Ely, and that in-progress church served as inspiration for much of the Ely building program.

East elevation (Romanesque), south east transept, after 1082, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Simeon’s building plans at Ely began in the east end with the choir and transepts. This is typical for churches, since their primary liturgical functions commonly take place in the east end of the church, oriented towards Jerusalem. This part of the church exemplifies the Romanesque style brought from Normandy after the Norman Conquest in 1066. It was completed in two different phases, which we can tell from the new decorative forms that appear on some of the capitals of the columns of the transepts, which were built later than the others.

Work on the nave was begun subsequently, and the south side was completed around 1109, when Ely was officially elevated to the status of a cathedral. Ely’s nave and transepts were some of the first spaces in England to display alternating forms of compound piers. This alternation adds visual rhythm, and diffuses the heaviness of these massive stone forms.

Like most Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, Ely’s nave elevation has three stories. The nave arcade with its alternating piers is on the ground floor. Above this is a gallery with double-light openings, or double, windowless arches, each pair set within a larger arch that mirrors the corresponding arch on the lower level. The third level is a clerestory with triplet openings. The tremendous thickness of the walls (a distinguishing feature of the Romanesque) is balanced by the proliferation of openings as one’s eyes travel upward. The viewer gets the sense that the building becomes lighter and brighter as it soars heavenward.

View from the graveyard beside the north east transept to the west tower, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The west towerthat tops the cathedral’s main entrance was built at the end of the twelfth century, towards the end of the Romanesque period in England.

Decorative façade with blind arcades and rounded arches, south west transept, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Experiments in the Gothic style brought over from France had already begun to take hold in England—particularly at Canterbury Cathedral and the northern Cistercianmonasteries. At Ely, though, the tower still exhibits round Romanesque arches instead of the pointed arches that are a hallmark of Gothic architecture.

The exterior is covered almost completely in blind arcading, an English speciality that stands in stark contrast to French medieval architecture, which prefers little extra surface decoration. Below the tower, we see a monumental entrance with blind pointed arches, which was added a bit later in the Early English Gothic style, showing how this new style was rapidly spreading across England during this time.

At the other end of the building, the presbytery was extended eastward in the 1230s and 1240s. In style, it draws from the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, completed just a decade or so earlier. With engaged colonnettes of Purbeck marble and white limestone, as well as complex rib vaults, it reflected the most fashionable architecture of the time. Then, as now, architectural styles came and went quickly, and the wealthiest and most powerful—such as the Bishop and diplomat Hugh of Northwold, who financed the new presbytery—had the means to stay current.

Nave arcade with Purbeck colonnettes, presbytery, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Eastern extensions were popular at this time to provide more room for the shrines of saints, like Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, or, at Ely, the shrine of Etheldreda. The presbytery was large enough to accommodate the many pilgrims who came to Ely to venerate the saint (and brought important income to the church and surrounding area). Having a highly-decorated space made this holy destination even more desirable.

In 1321, a new chapel was begun north of the presbytery, which would eventually become one of the most beautiful and artistically innovative of the English Gothic period. But in the early morning hours of February 13, 1322, just as the monks were finishing their morning prayers, disaster struck. The crossing tower of the cathedral collapsed, crushing parts of the choir, and construction on the chapel had to stop.

Though this collapse was devastating, it made room for one of the most remarkable structures of the English Middle Ages. Alan of Walsingham, sub-prior and sacrist of Ely, quickly initiated the building of a new tower—a tall, octagonal structure (often referred to as “the Octagon”) surmounted by a tower made of timber clad with lead. This type of tower is called a lantern because it is pierced to allow light in. Vaults with tiercerons spring from the base of the Octagon, creating a star-like effect when one looks up.

Lantern with central roof boss that incorporates a sculpture of the Risen Christ, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In the supporting structure below, Etheldreda was commemorated with capitals depicting scenes from her life. These include her marriage to Igfrid, and her rest on the way from Northumberland to Ely. The Octagon, from floor to the central roof boss, is 142 feet tall, the same height as the Pantheon in Rome. This correspondence may have been intentional, since the Octagon is like a Gothic version of the Pantheon’s incredible dome, and the tower above it delivers light throughout, like the opening of the Roman temple.

Lady Chapel, Ely (note fragments of original stained glass, upper left) photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Once the Octagon was completed, attention was turned back to the Lady Chapel. A Lady Chapel is a space dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and this one is especially clear in its depiction of her life and miracles. The chapel, built in the Decorated Style, is rectangular, and its elevation is composed of a dado and clerestory. A series of niches encircle the room, forming the dado.

Niches near altar that form the dado, Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Each niche is protected with a nodding ogee canopy and ornamented with relief sculpture relating to the Virgin. It has been observed that the sculptural niches of the dado have a vulvular shape, perhaps not coincidental given that the chapel celebrates the Virgin Mary, whose chief contribution to Christian history was giving birth to Jesus.

Ogee, Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral (note that the heads of the figures have been broken off), photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Lady Chapel was interrupted by the collapse of the central tower, and its progress may have been troubled again by the Black Death, which struck England in 1348. On the western side of the chapel, the nodding ogees of the dado flatten, and the diaper-work is halted. The vault fits uneasily on the chapel. Scholars suspect that some of the sculptors and masons at Ely may have fallen victim to the plague, leaving the lavish project to be completed by their less adept colleagues.

Although the Ely Lady Chapel is one of the most beautiful interiors of English medieval art, it’s also one of the most heavily destroyed. During the English Reformation, the sculptures were mutilated because religious imagery was thought to be idolatrous. The images were taken from their niches, and the colorful stained glass that would have filled the windows was destroyed. Some sculpture remains in the life of the Virgin series on the dado, but many have been stripped of their heads or more. Traces of polychromy remain, but are but a pale shadow of the formerly brilliant space.

Surviving fragments of stained glass, Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral, photo: Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

After the Black Death, a final style of the English Middle Ages emerges as the primary mode of building. This is called the Perpendicular Style because, unlike the flowing, undulating curves of the Decorated Style that preceded it, it emphasizes straight lines and vertical projections. The Perpendicular Style took hold in the second half of the fourteenth century, and continued through the remainder of the Middle Ages—almost two hundred years!

Souls being led out of Purgatory, from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, folio 107r, c.1440 (The Morgan Library)

Bishop Alcock’s chantry chapel was built in the Perpendicular Style between 1488 and 1500. A chantry chapel is a space devoted to praying for an individual or a family in order to shorten their time in purgatory. Purgatory was understood to be a fiery place where souls went after death, but unlike hell, one could eventually leave purgatory after serving the required amount of time necessary for sins committed during life. A reduction of one’s sentence in purgatory could be achieved, either during life from the acquisition of indulgences, or in death if one’s loved ones or the executors of their wills prayed for them and ensured that masses were said in their honor.

Alcock is likely to have planned the chapel himself—he had been the Controller of the Royal Works and Buildings under King Henry VII. The chapel is cordoned off from the north aisle with a microarchitectural screen with statue niches that are now empty. Though this screen is extremely intricate and beautifully carved, it doesn’t quite fit in the space allotted for it. Prior to becoming bishop of Ely, Alcock had held the same post at Worcester Cathedral. It is thought that the chapel may have been planned for a large space there, but was instead jammed into tighter accommodations at Ely. Within the chapel is Alcock’s tomb, in a niche, and an altar so that Masses could be said for his soul. Alcock’s memory was also made explicit with the use of his rebus with a cock (rooster) atop a globe, and his coat of arms, three cocks.

The “ship of the Fens” is a wonderful example of the evolution of English architectural style in the Middle Ages: from Romanesque to Early English Gothic, Decorated, and Perpendicular. The people who built churches in the Middle Ages wouldn’t have thought of themselves as building in these styles, however—these are names given by historians in the nineteenth century to describe them retrospectively. The builders themselves would have thought of what they were building simply as “current.” Although Etheldreda sought refuge her marriage in the quiet, eel-filled marshes of Ely, the Middle Ages saw this site develop into a far more elaborate space than she could possibly have imagined.

Additional resources:

Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland entry on Ely Cathedral

Illustrations for some definitions borrowed from the Glossary of Medieval Art and Architecture.

John Maddison, Ely Cathedral: Design and Meaning (Ely: Ely Cathedral Publications, 2000).

Source: Meg Bernstein, “Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral,” in Smarthistory, October 26, 2018, accessed November 25, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/ely-cathedral/.

Art Historian Paul Binski believes it is possible to recover the Lady Chapel’s former opulence in the imagination. His talk gives an insight into the psychology behind Ely’s splendour, and the idea that art can be so powerful as to provoke violence—something we still see in headlines today.

Paul Binski – Ely Cathedral’s Lady Chapel: Devotion and Destruction from HENI Talks on YouTube. URL: https://youtu.be/vktMCKXhtSU

York Minster (The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter), begun 1220, consecrated 1472; Chapter House completed by 1296. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. URL: https://youtu.be/iN3sw6luG0o

Additional resources

Explore an interactive map of York Minster

Synagoga and Ecclesia, Strasbourg Cathedral

Depicting Judaism in a medieval Christian ivory

Sarah Brown, “The Chapter House and Its Vestibule,” Stained Glass at York Minster (London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc., 2017), pp. 24–31.

Sarah Brown, York Minster: An Architectural History c. 1220–1500 (Swindon: English Heritage, 2003).

URL: https://youtu.be/YCKzhNQISZo

Ground plan of the Henry VII chapel, adjoining Westminster Abbey, with the details of the fan vault superimposed over the plan; illustration to the Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain, vol II. 1808 (The British Museum)

View on Google Maps

URL: https://youtu.be/Z2Zmmx0u-gE

See also: This painting at The National Gallery

Cite this page as: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “The Wilton Diptych,” in Smarthistory, December 11, 2015, accessed November 25, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/the-wilton-diptych/.

Matthew Paris’s itinerary maps from London to Palestine. Despite having never been to Palestine, the monk and historian Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1260), created an itinerary from London to Palestine.