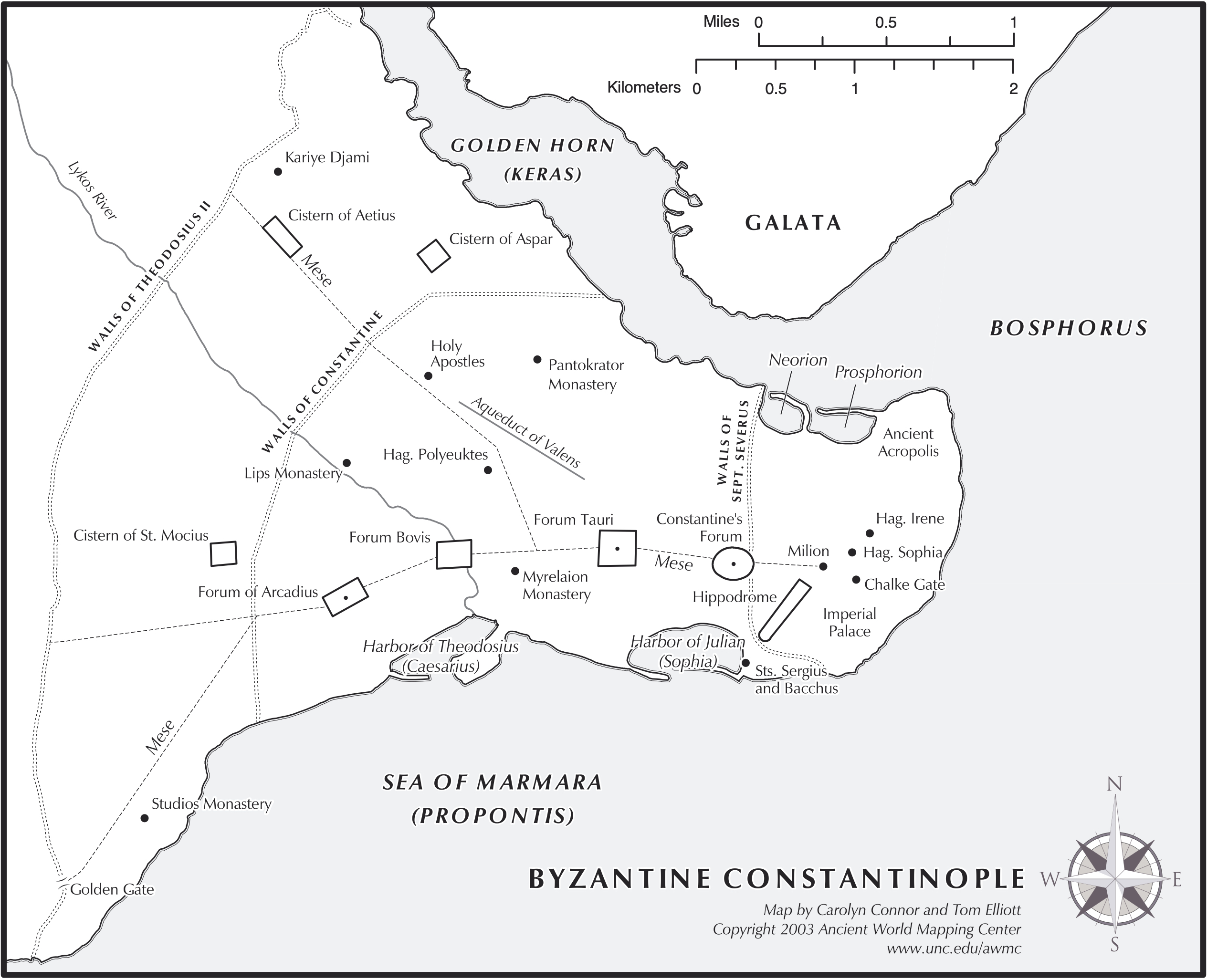

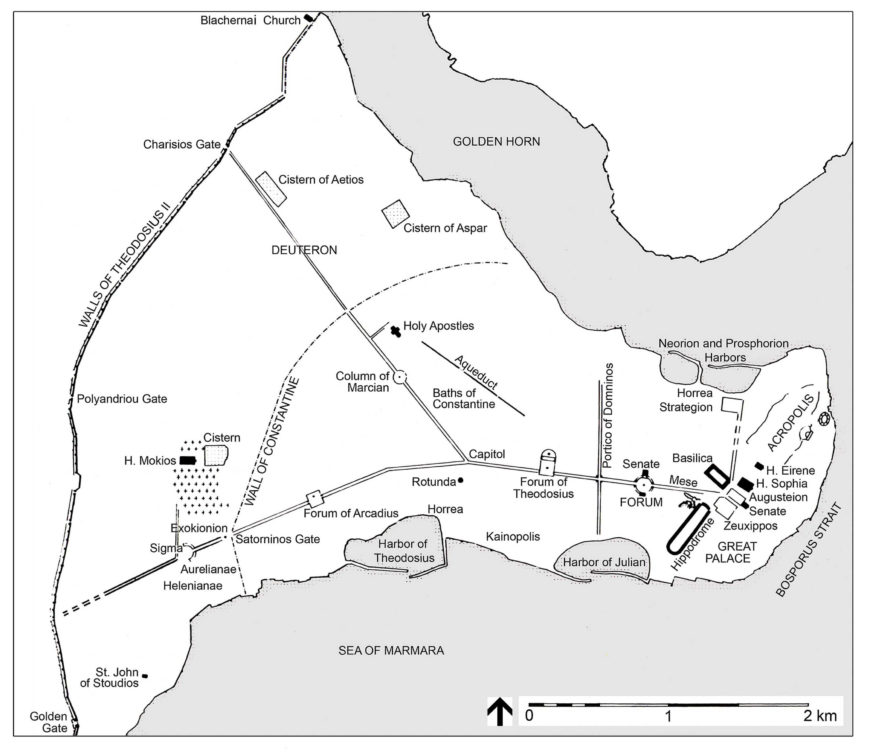

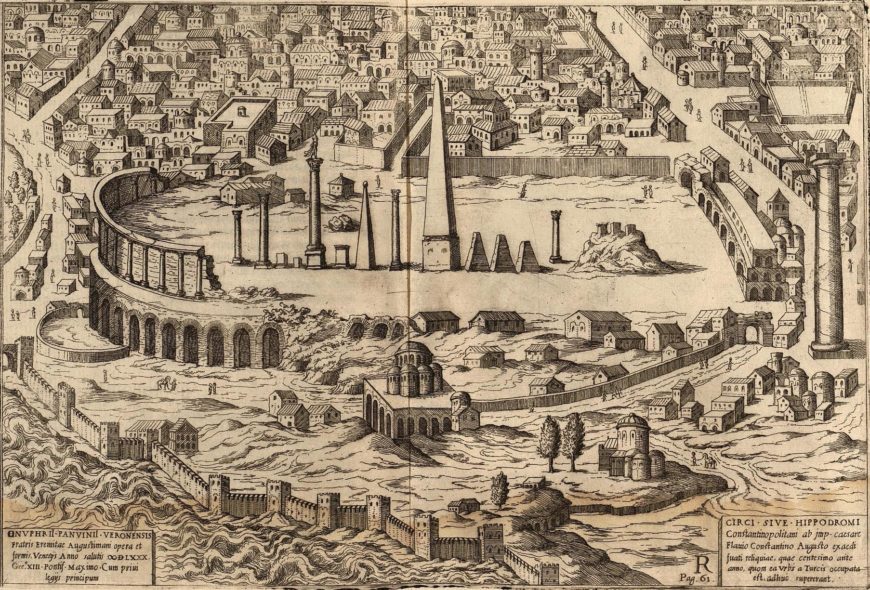

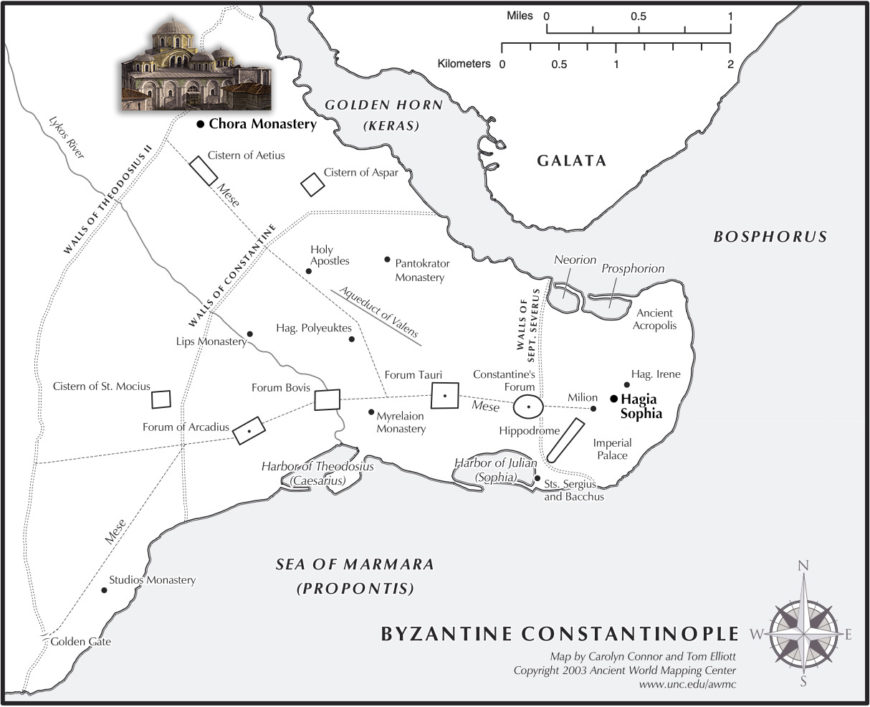

Following the example of Rome, Constantinople featured a number of outdoor public spaces—including major streets, fora, as well as a hippodrome (a course for horse or chariot racing with public seating)—in which emperors and church officials often participated in showy public ceremonies such as processions.

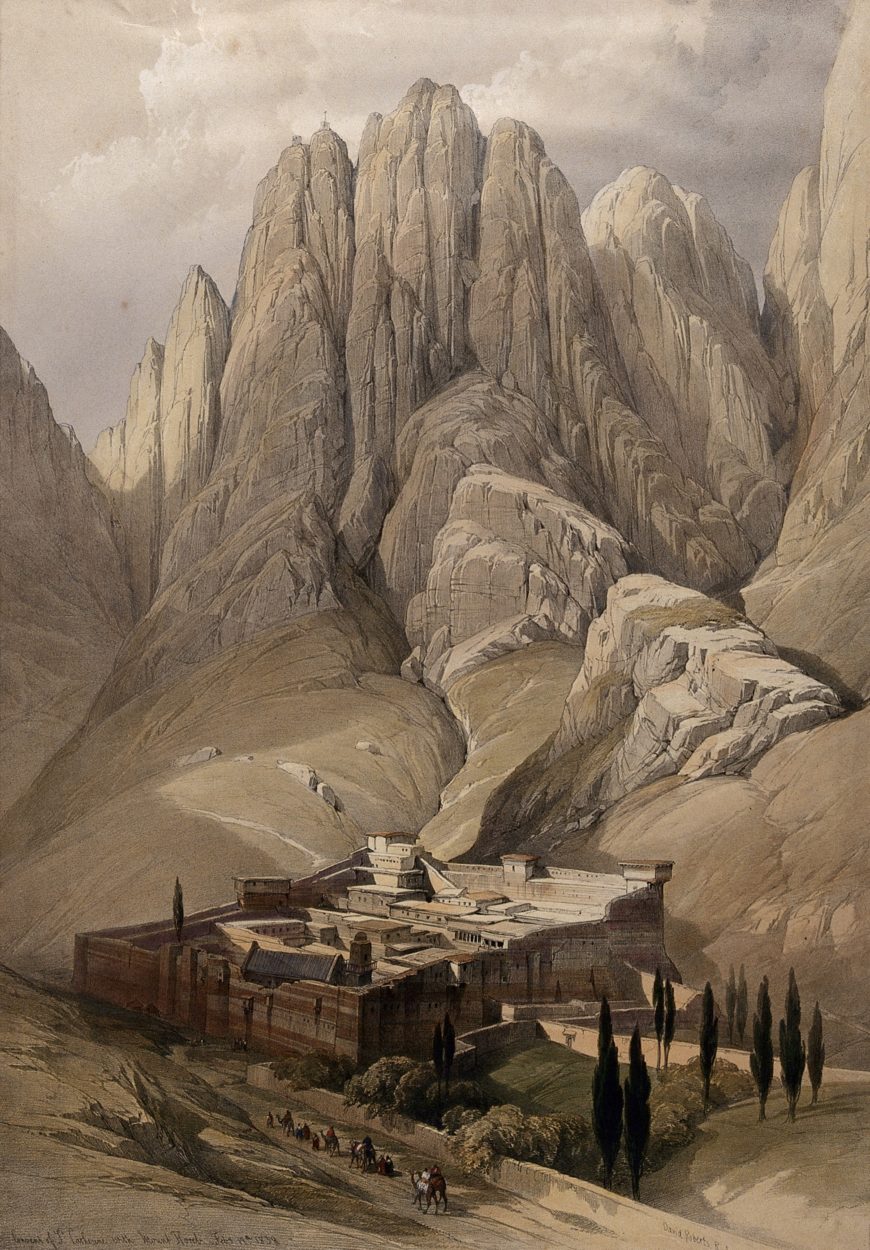

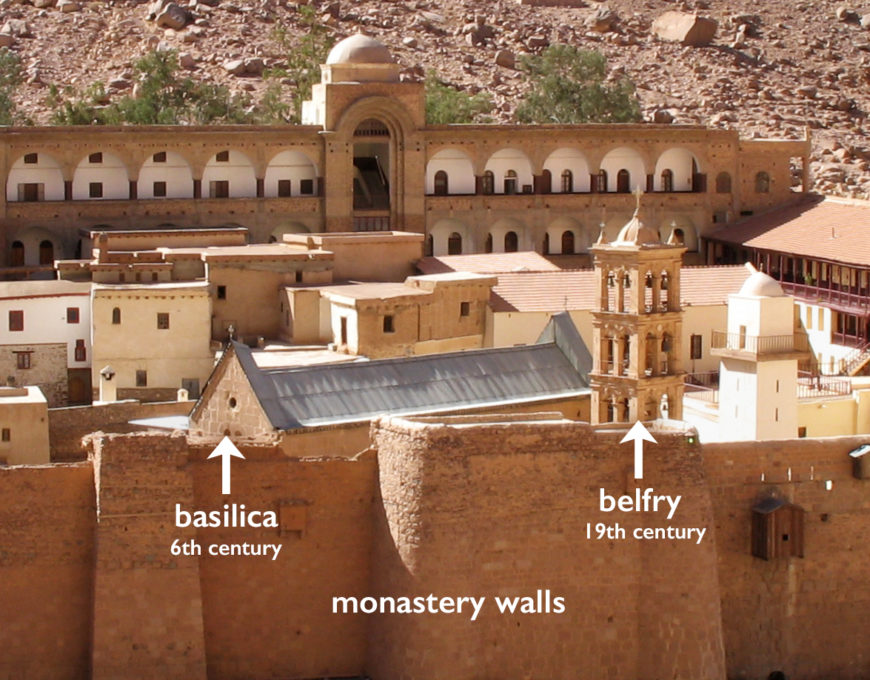

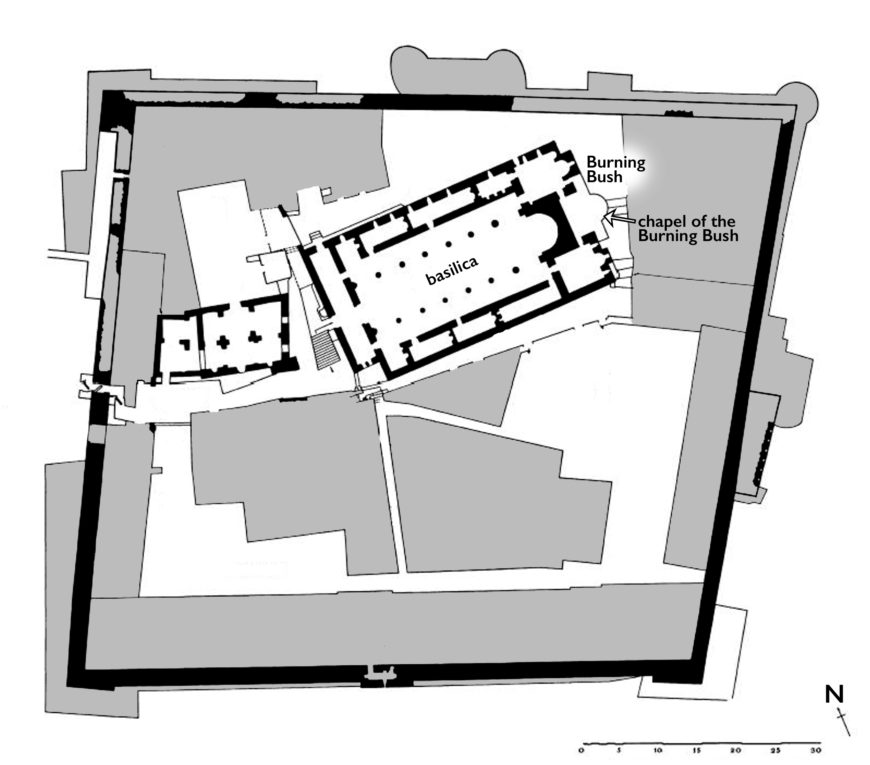

Christian monasticism, which began to thrive in the 4th century, received imperial patronage at sites like Mount Sinai in Egypt.

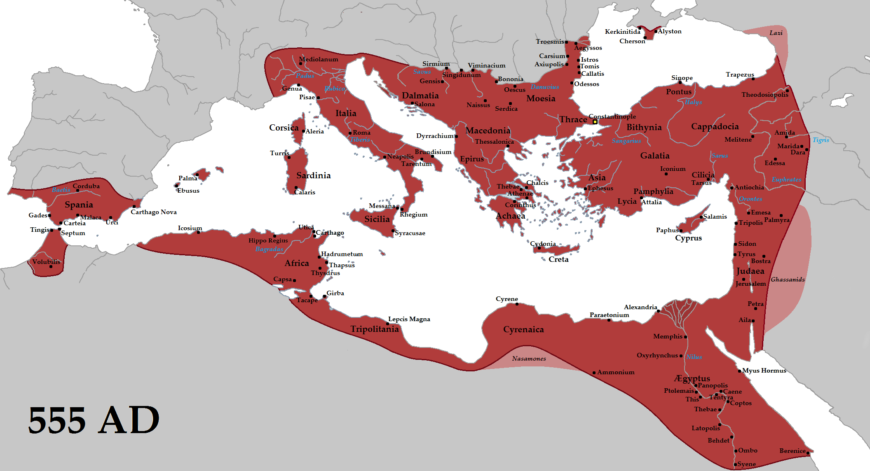

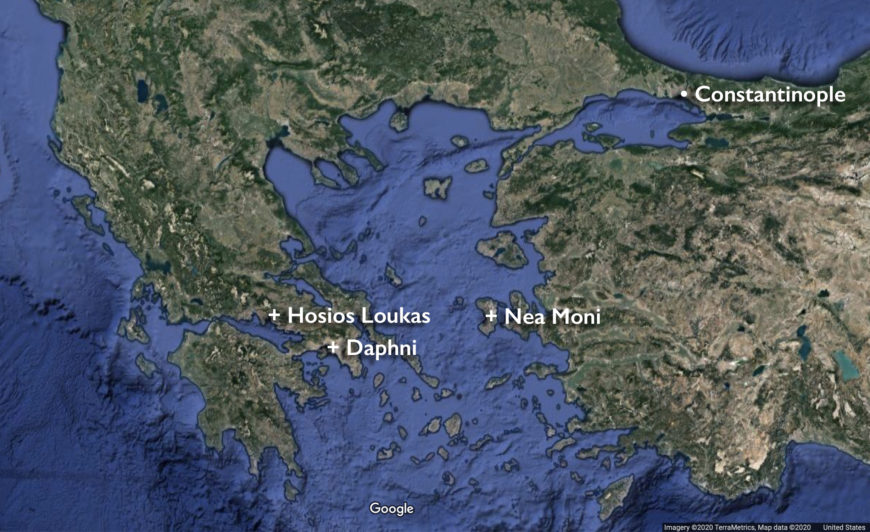

Yet the mid-7th century began what some scholars call the “dark ages” or the “transitional period” in Byzantine history. Following the rise of Islam in Arabia and subsequent attacks by Arab invaders, Byzantium lost substantial territories, including Syria and Egypt, as well as the symbolically important city of Jerusalem with its sacred pilgrimage sites. The empire experienced a decline in trade and an economic downturn.

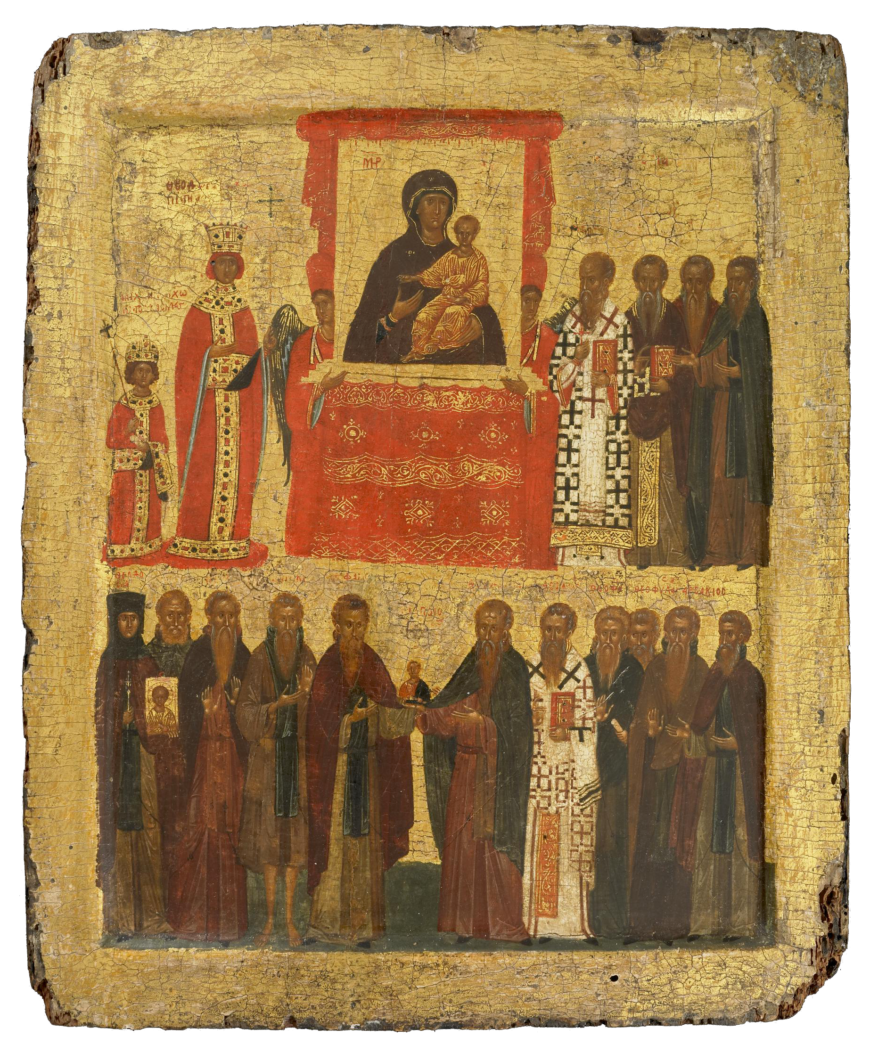

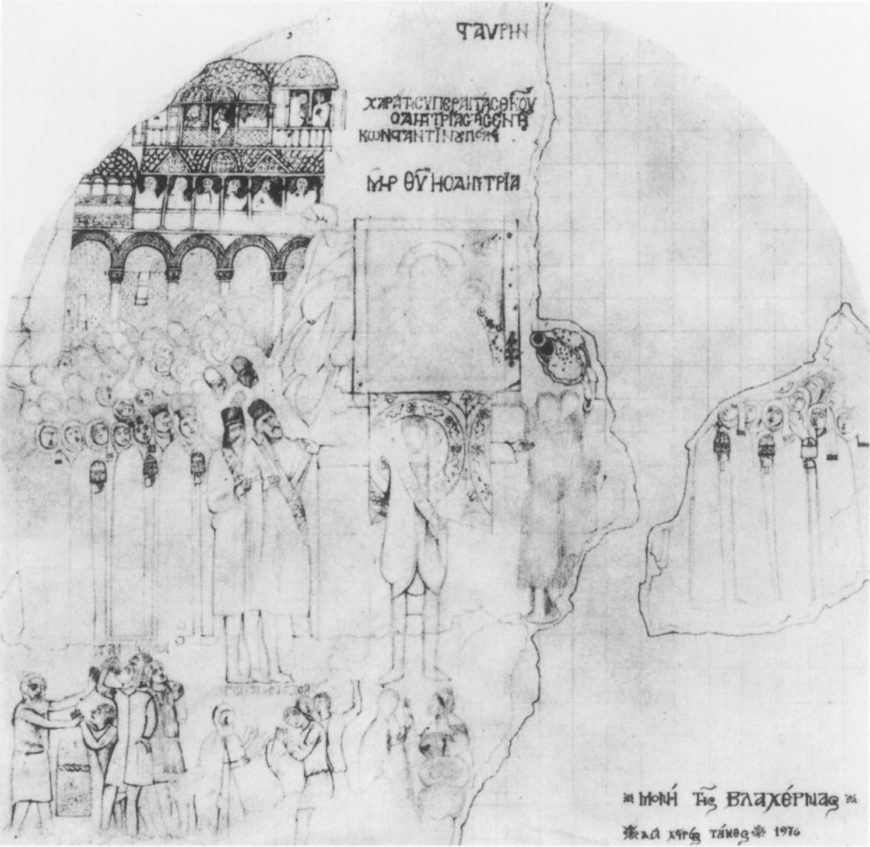

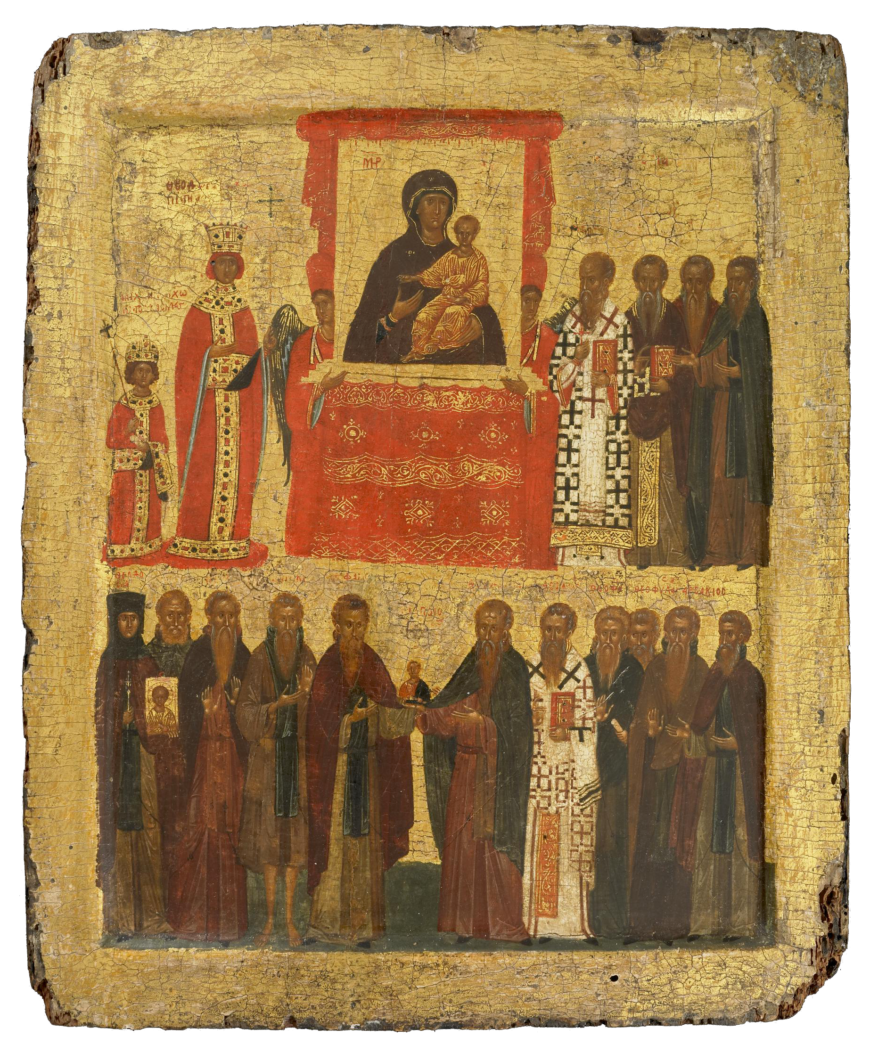

Against this backdrop, and perhaps fueled by anxieties about the fate of the empire, the so-called “Iconoclastic Controversy” erupted in Constantinople in the 8th and 9th centuries. Church leaders and emperors debated the use of religious images that depicted Christ and the saints, some honoring them as holy images, or “icons,” and others condemning them as idols (like the images of deities in ancient Rome) and apparently destroying some. Finally, in 843, Church and imperial authorities definitively affirmed the use of religious images and ended the Iconoclastic Controversy, an event subsequently celebrated by the Byzantines as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

In the period following Iconoclasm, the Byzantine empire enjoyed a growing economy and reclaimed some of the territories it lost earlier. With the affirmation of images in 843, art and architecture once again flourished. But Byzantine culture also underwent several changes.

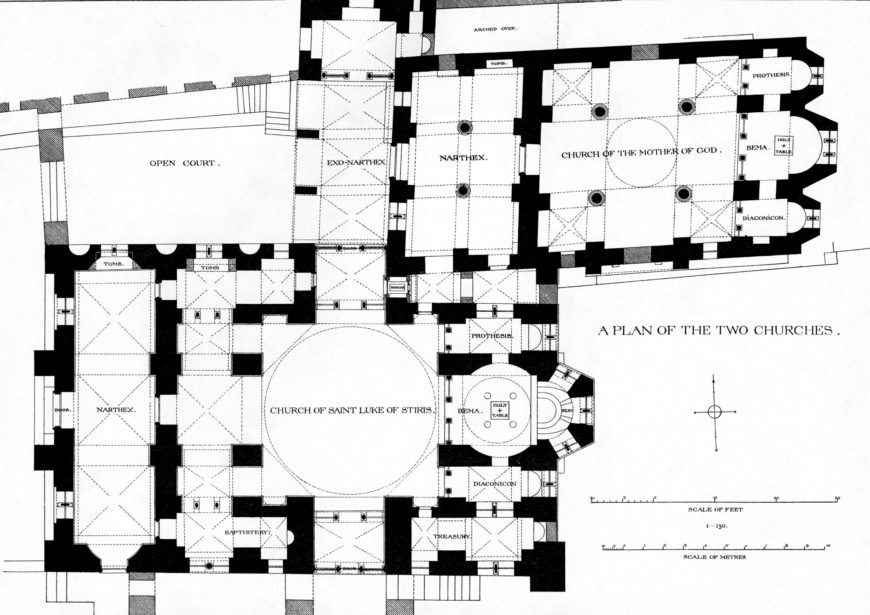

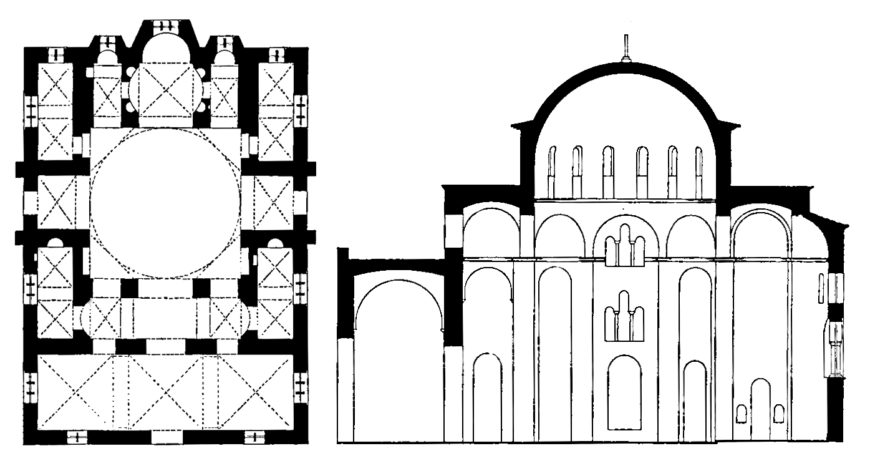

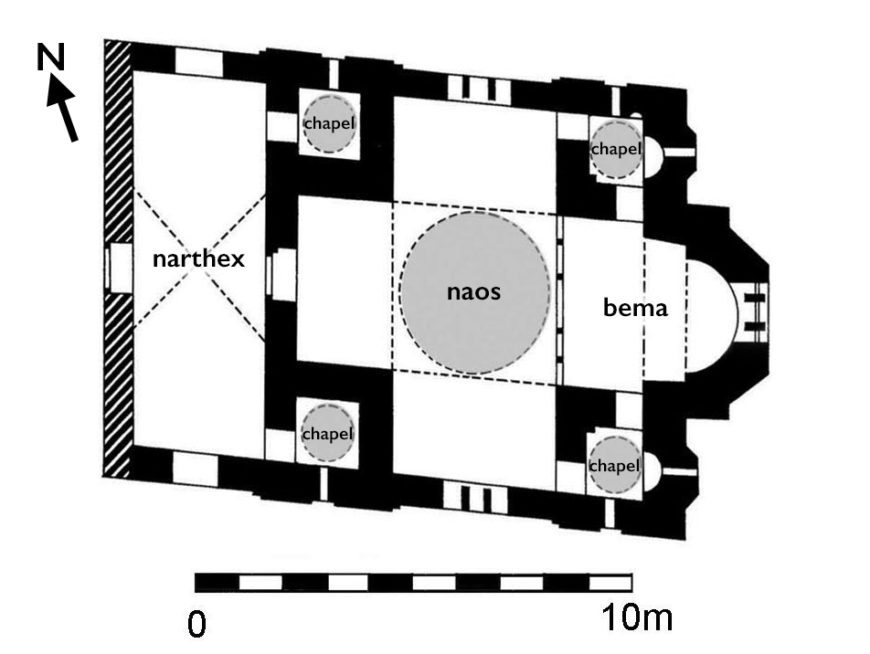

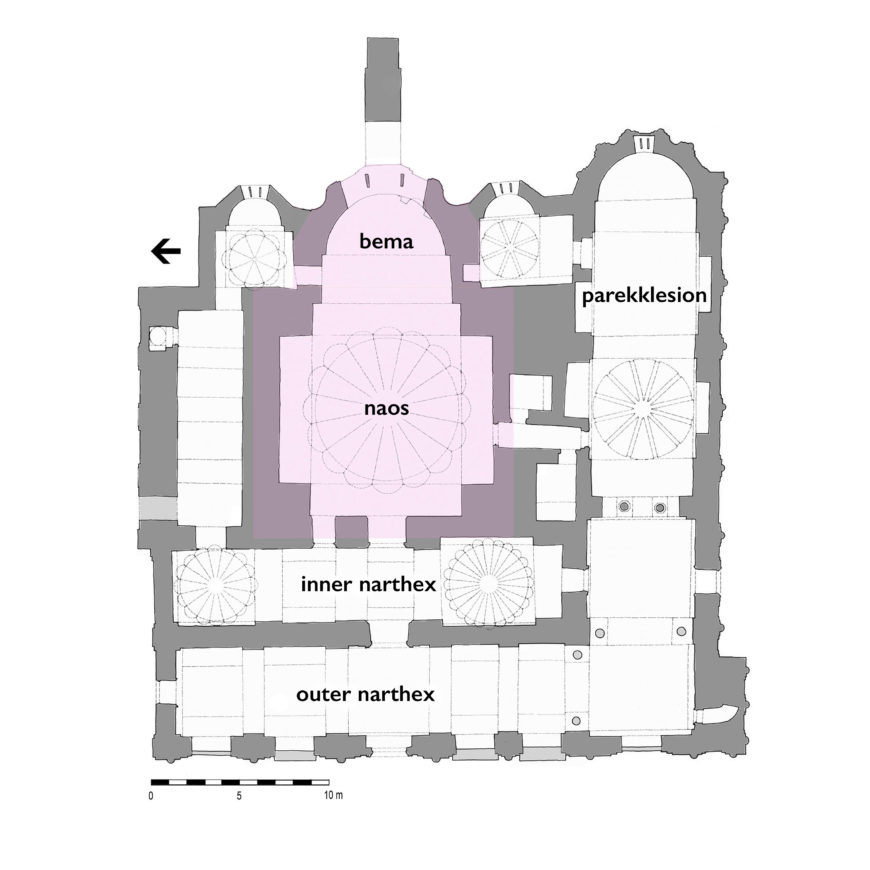

Middle Byzantine churches elaborated on the innovations of Justinian’s reign, but were often constructed by private patrons and tended to be smaller than the large imperial monuments of Early Byzantium. The smaller scale of Middle Byzantine churches also coincided with a reduction of large, public ceremonies.

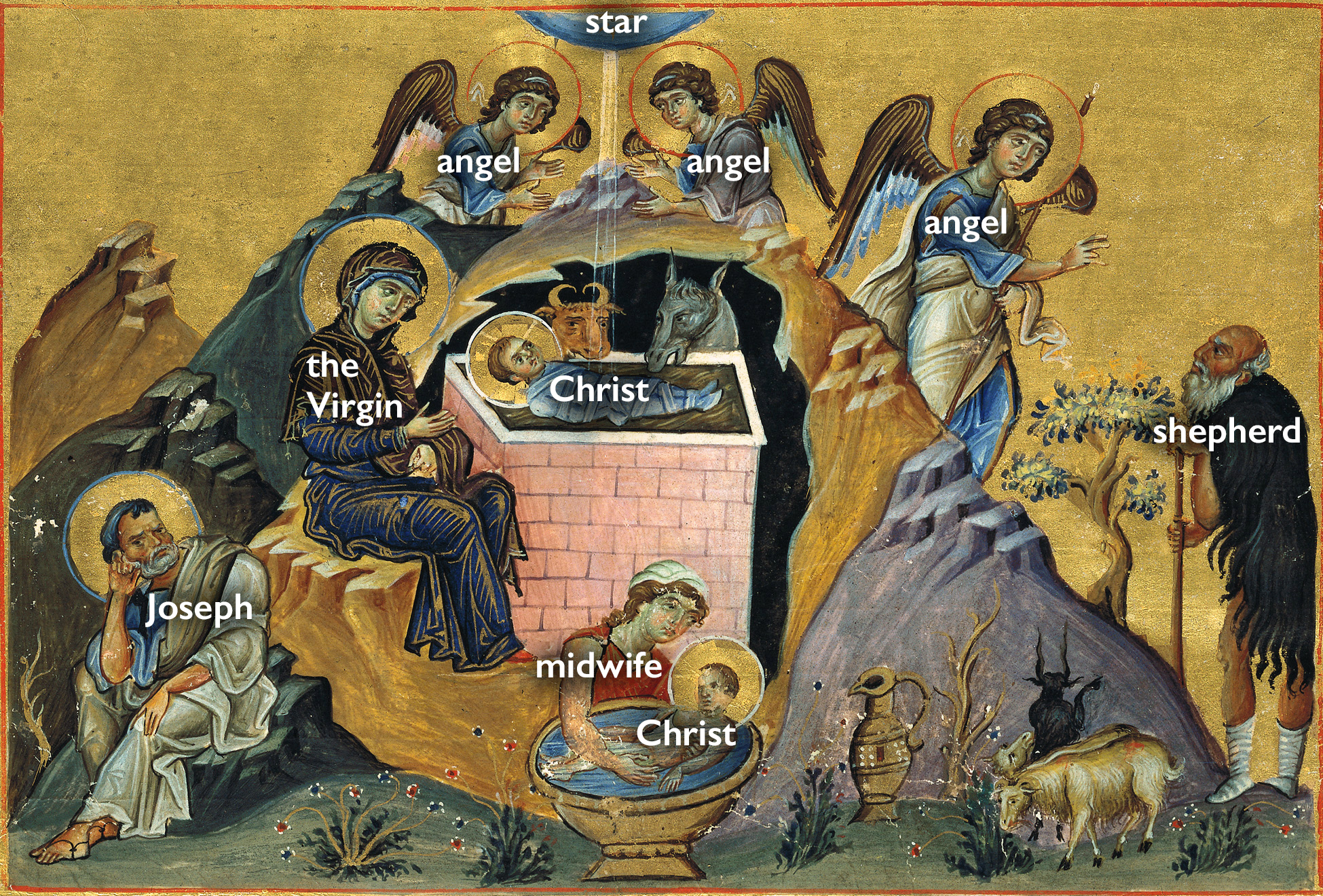

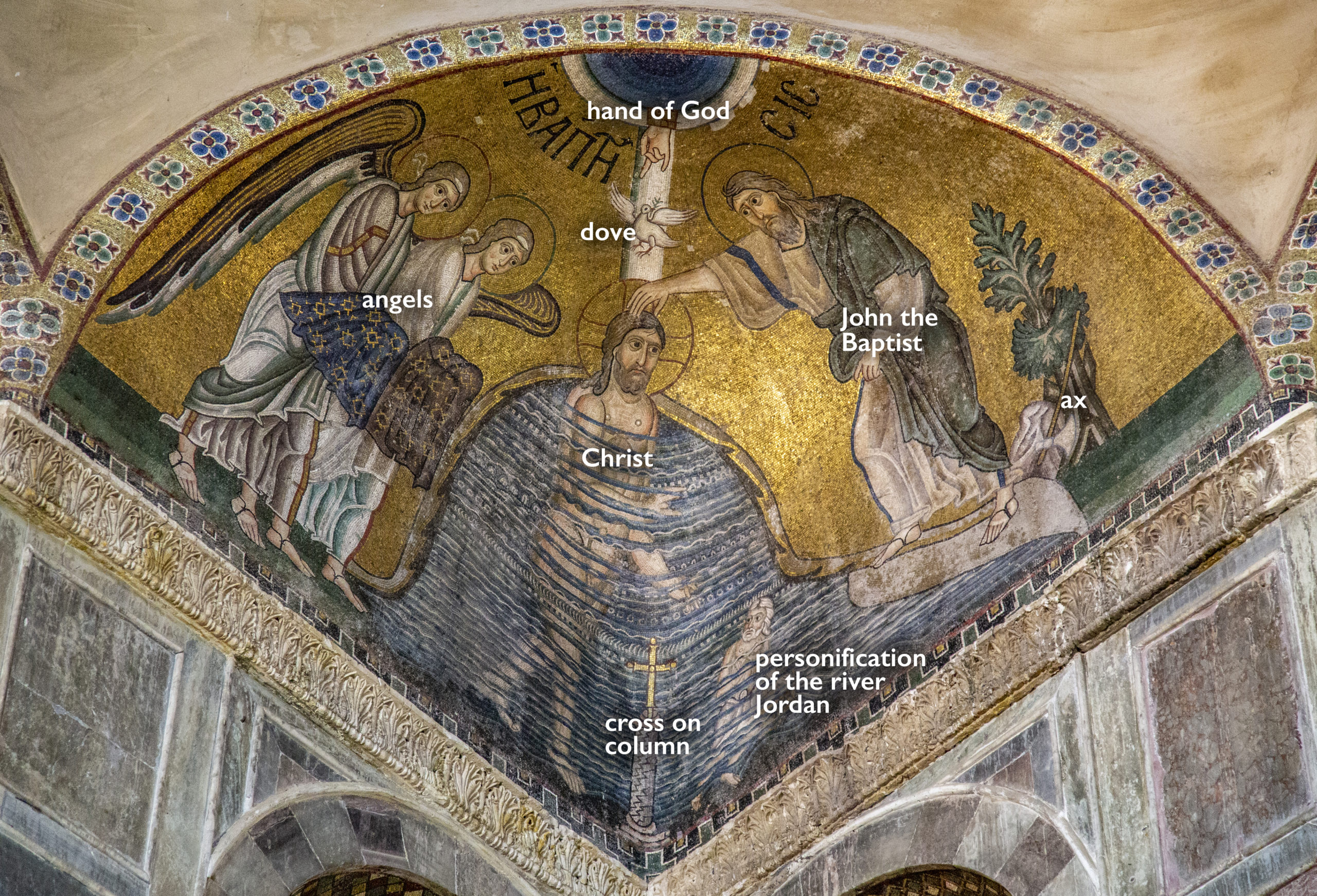

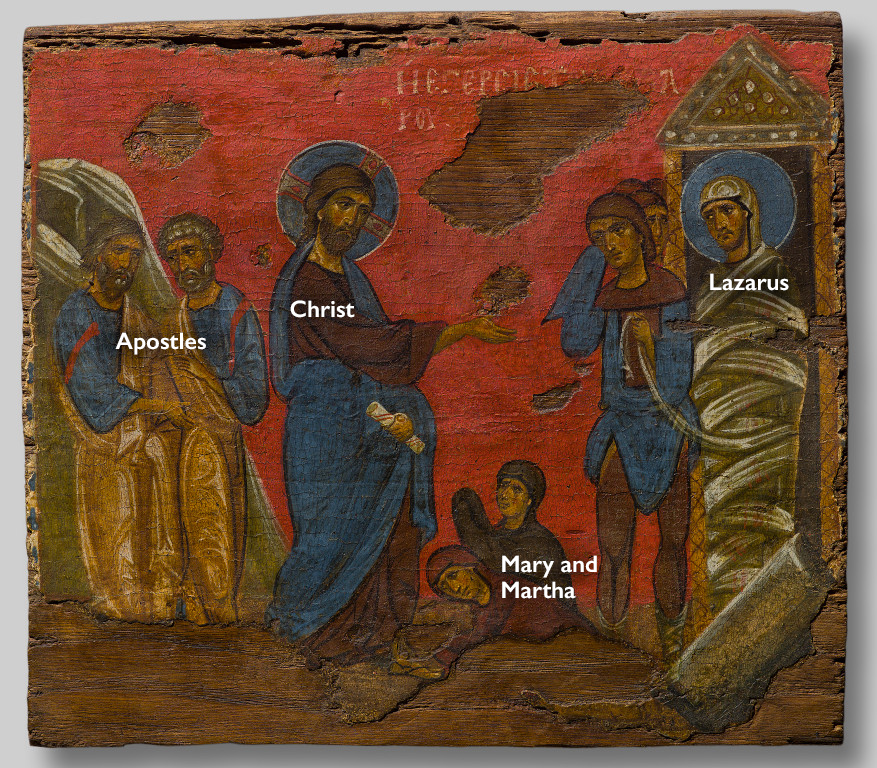

Monumental depictions of Christ and the Virgin, biblical events, and an array of various saints adorned church interiors in both mosaics and frescoes. But Middle Byzantine churches largely exclude depictions of the flora and fauna of the natural world that often appeared in Early Byzantine mosaics, perhaps in response to accusations of idolatry during the Iconoclastic Controversy. In addition to these developments in architecture and monumental art, exquisite examples of manuscripts, cloisonné enamels, stonework, and ivory carving survive from this period as well.

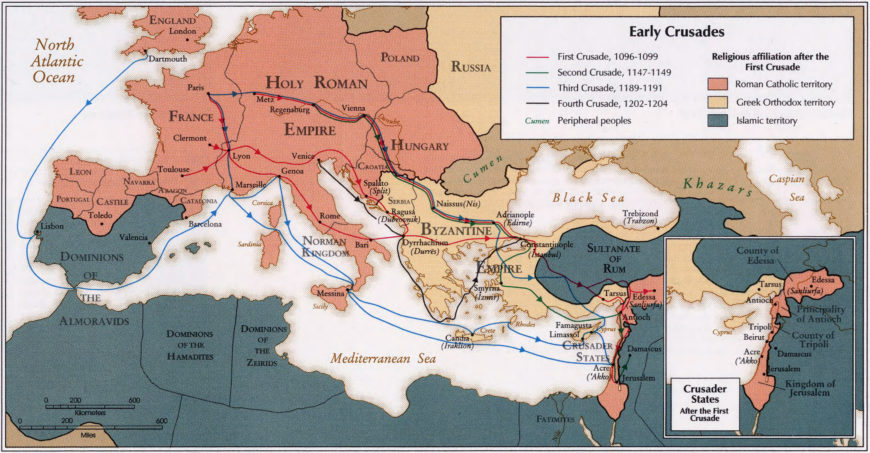

The Middle Byzantine period also saw increased tensions between the Byzantines and western Europeans (whom the Byzantines often referred to as “Latins” or “Franks”). The so-called “Great Schism” of 1054 signaled growing divisions between Orthodox Christians in Byzantium and Roman Catholics in western Europe.

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade—undertaken by western Europeans loyal to the pope in Rome—veered from its path to Jerusalem and sacked the Christian city of Constantinople. Many of Constantinople’s artistic treasures were destroyed or carried back to western Europe as booty. The crusaders occupied Constantinople and established a “Latin Empire” in Byzantine territory. Exiled Byzantine leaders established three successor states: the Empire of Nicaea in northwestern Anatolia, the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia, and the Despotate of Epirus in northwestern Greece and Albania. In 1261, the Empire of Nicaea retook Constantinople and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as emperor, establishing the Palaiologan dynasty that would reign until the end of the Byzantine Empire.

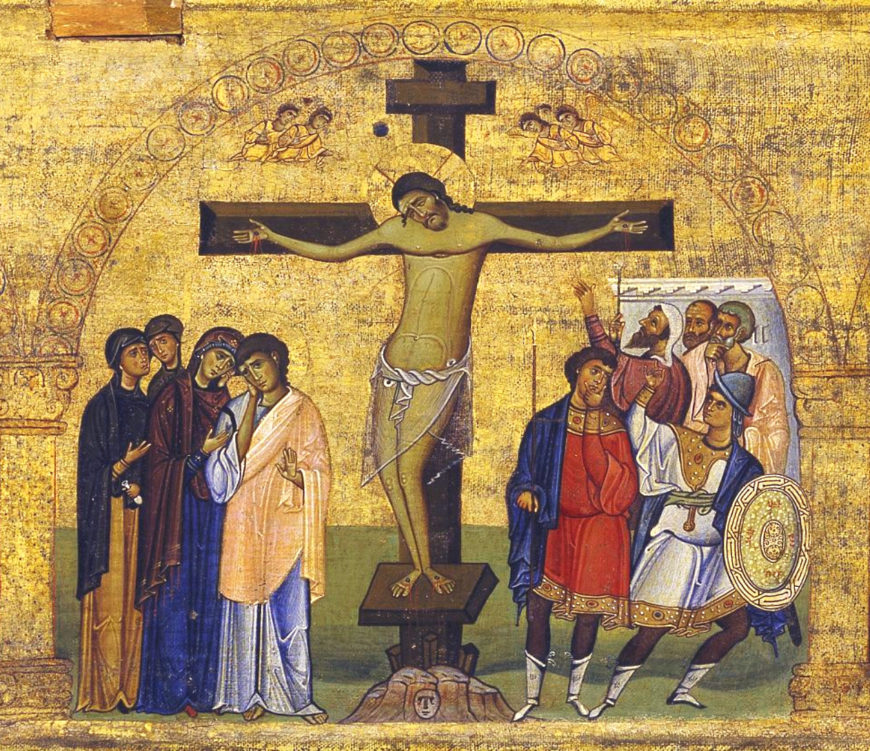

While the Fourth Crusade fueled animosity between eastern and western Christians, the crusades nevertheless encouraged cross-cultural exchange that is apparent in the arts of Byzantium and western Europe, and particularly in Italian paintings of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, exemplified by new depictions of St. Francis painted in the so-called Italo-Byzantine style.

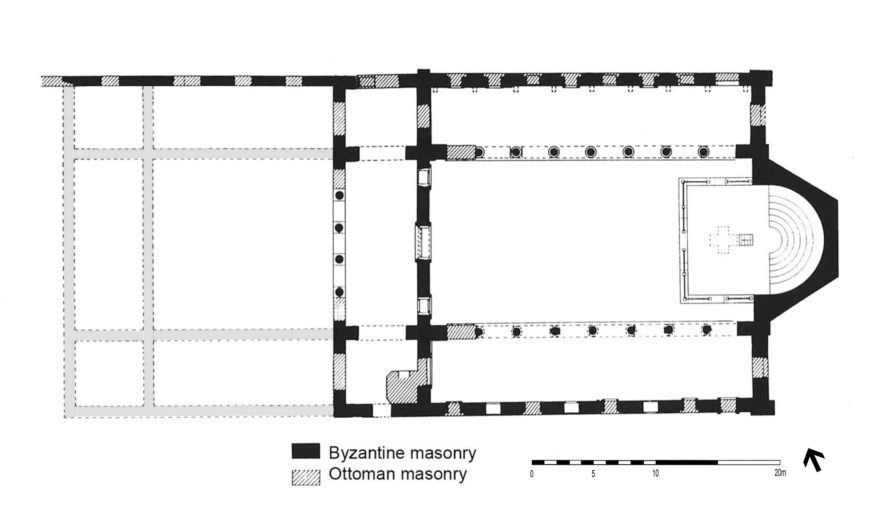

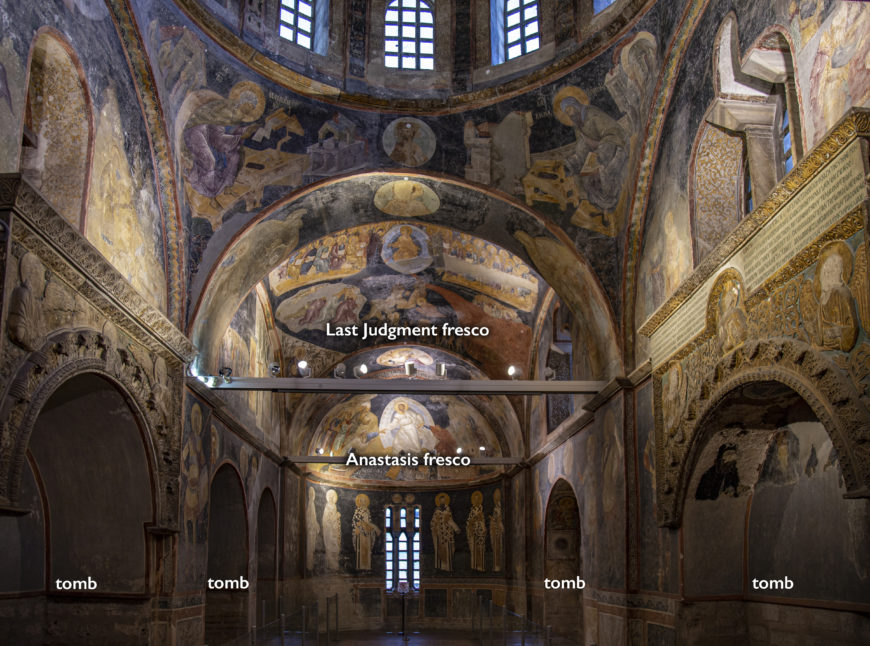

Artistic patronage again flourished after the Byzantines re-established their capital in 1261. Some scholars refer to this cultural flowering as the “Palaiologan Renaissance” (after the ruling Palaiologan dynasty). Several existing churches—such as the Chora Monastery in Constantinople—were renovated, expanded, and lavishly decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Byzantine artists were also active outside Constantinople, both in Byzantine centers such as Thessaloniki, as well as in neighboring lands, such as the Kingdom of Serbia, where the signatures of the painters named Michael Astrapas and Eutychios have been preserved in frescos from the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

Yet the Byzantine Empire never fully recovered from the blow of the Fourth Crusade, and its territory continued to shrink. Byzantium’s calls for military aid from western Europeans in the face of the growing threat of the Ottoman Turks in the east remained unanswered. In 1453, the Ottomans finally conquered Constantinople, converting many of Byzantium’s great churches into mosques, and ending the long history of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Despite the ultimate demise of the Byzantine Empire, the legacy of Byzantium continued. This is evident in formerly Byzantine territories like Crete, where the so-called “Cretan School” of iconography flourished under Venetian rule (a famous product of the Cretan School being Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco).

But Byzantium’s influence also continued to spread beyond its former cultural and geographic boundaries, in the architecture of the Ottomans, the icons of Russia, the paintings of Italy, and elsewhere.

In our time, we often refer to celebrities as cultural icons, pop icons, and fashion icons. Rebels are sometimes labeled iconoclasts. Icons are also the little images that populate the screens of our computers, phones, and tablets, which we click to open files and apps.

The word “icon” comes from the Greek eikо̄n, so, “icon” simply means image. In the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and other lands that shared Byzantium’s Orthodox Christian faith, “holy icons” were images of sacred figures and events.

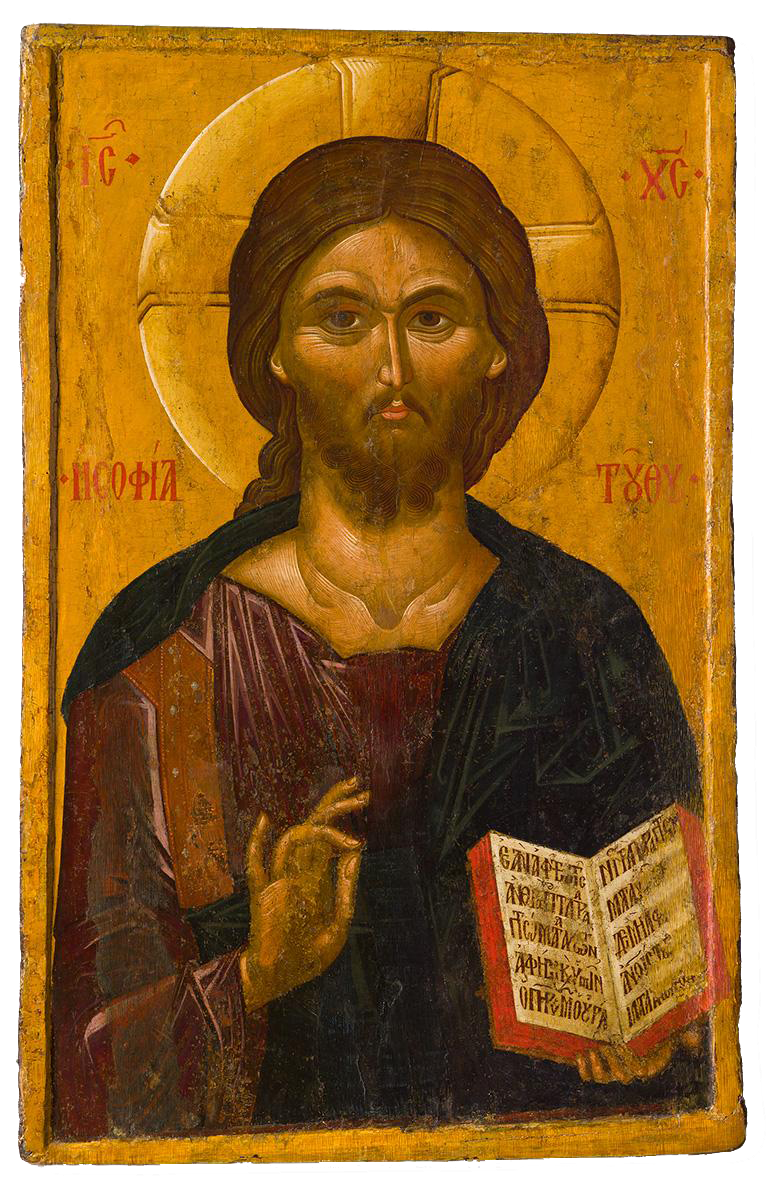

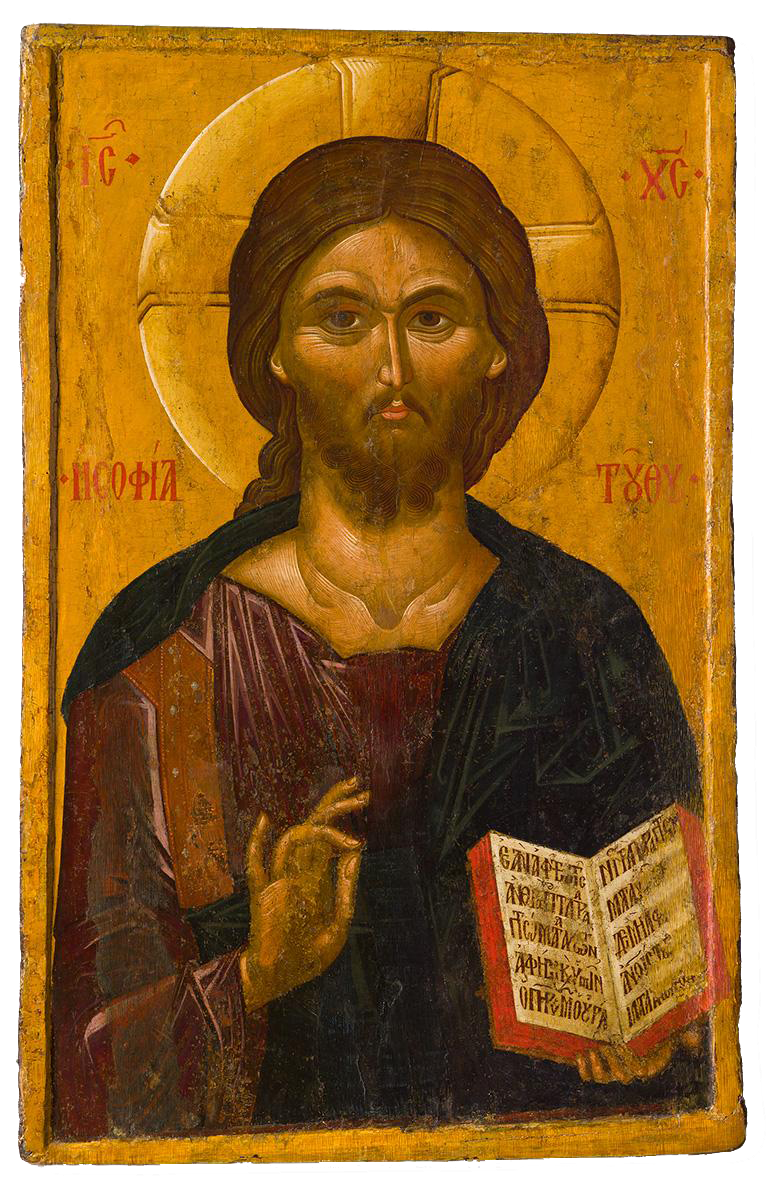

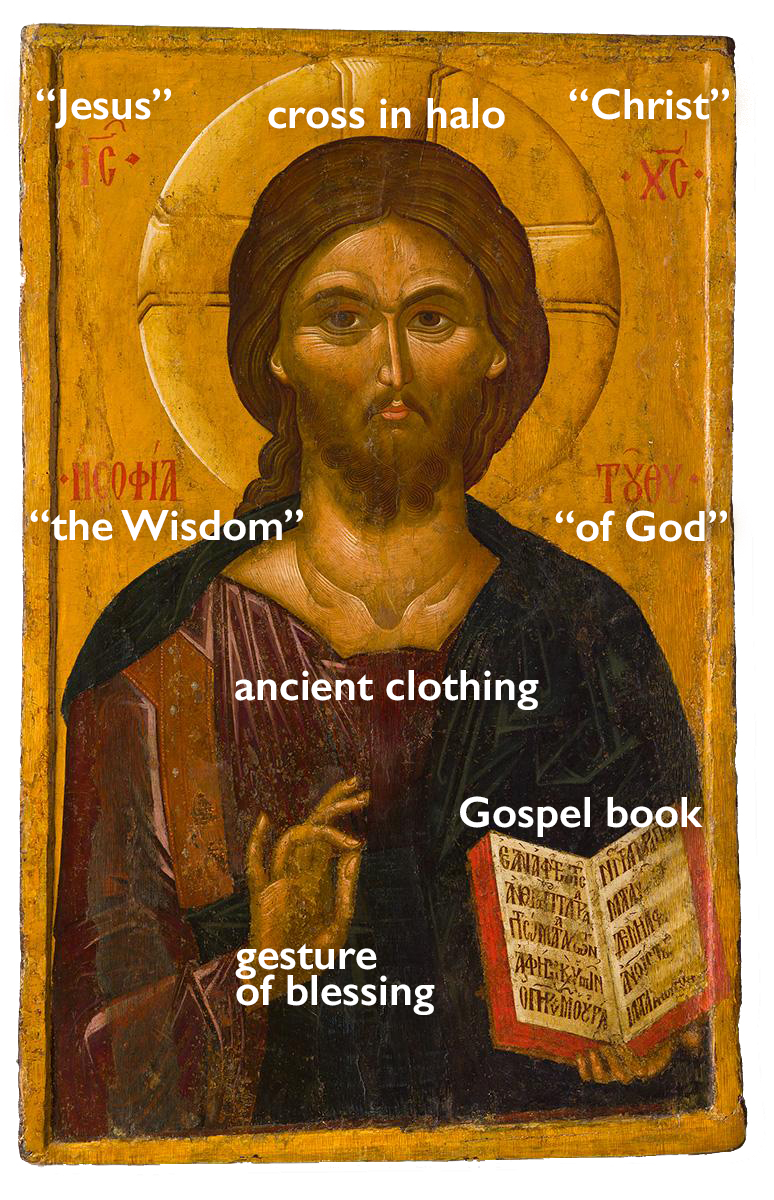

Icon of Christ, late 14th century, Thessaloniki, egg tempera on wood, 157 x 105 x 5 cm (Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki)

When art historians talk about icons today, they often mean portraits of holy figures painted on wood panels with encaustic or egg tempera, like this tempera icon of Christ from fourteenth-century Thessaloniki. But the Byzantines used the term icon more broadly, as this statement made by Church authorities in 787 C.E. shows:

Holy icons—made of colors, pebbles, or any other material that is fit—may be set in the holy churches of God, on holy utensils and vestments, on walls and boards, in houses and in streets. These may be icons of our Lord and God the Savior Jesus Christ, or of our pure Lady the holy Theotokos, or of honorable angels, or of any saint or holy man.(Council of Nicaea II, 787 C.E.)

The Byzantines created icons in virtually every available medium. Left to right: heliotrope (bloodstone) cameo icon of Christ, 10th century, Byzantine (The British Museum); ivory icon with the Koimesis (Dormition of the Virgin), late 10th century, Constantinople (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); miniature mosaic icon of the Virgin and Child, early 14th century, Constantinople (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Chalice decorated with icons of holy figures, 500–650, Attarouthi, Syria (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

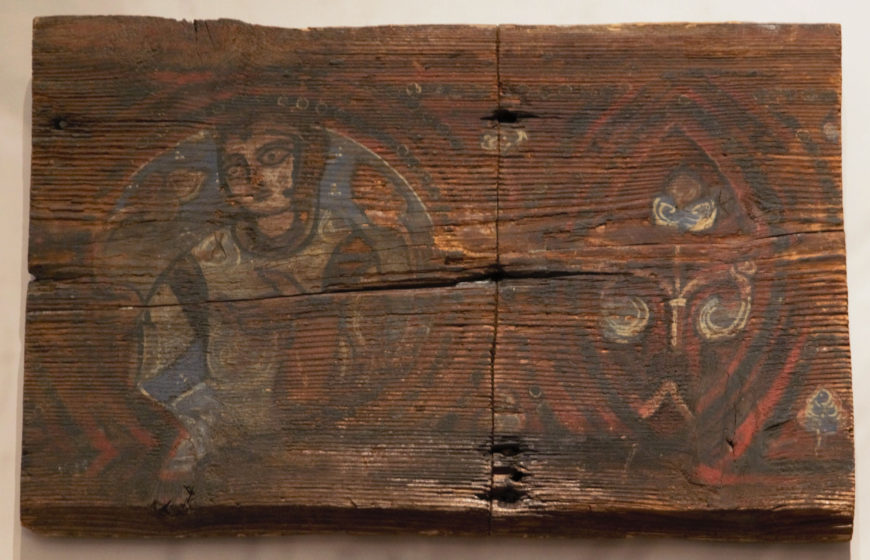

In Byzantium, icons were painted, but they were also carved in stone and ivory and fashioned from mosaics, metals, and enamels—virtually any medium available to artists.

Icons could be monumental or miniature. They were located in a variety of religious and non-religious settings, including as decoration on functional objects like this Eucharistic chalice.

And icons could depict a wide range of sacred subjects, such as Christ, the saints, and events from the Bible or the lives of saints.

Mosaic icon of Christ above the entrance to the 11th-century church at Hosios Loukas Monastery, Boeotia, Greece (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Iconoclasm and the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”

Christians initially disagreed over whether religious images were good or bad. Texts from as early as the second and third century describe some Christians using religious images, which they illuminated and adorned with garlands, but these practices were not universal or standardized. Church authorities often criticized these practices, which reminded them of customs associated with pagan Greece and Rome, where images of gods and emperors were widely venerated.

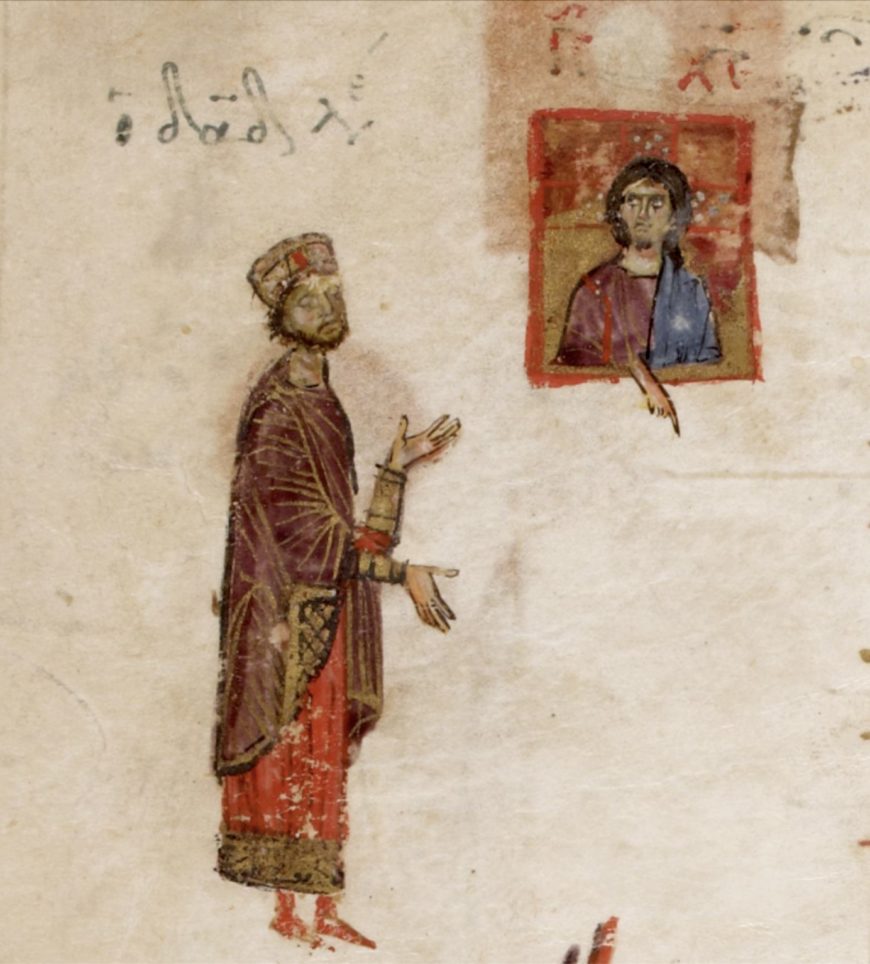

Iconoclasts whitewashing an icon of Christ, miniature in the Theodore Psalter (Add MS 19352, fol. 27v), 1066, Constantinople (The British Library)

By the eighth and ninth centuries, icons were increasingly popular, and arguments about religious images boiled over in what is called the “Iconoclastic Controversy.” The so-called “iconoclasts” (literally, “breakers of images”) opposed icons, arguing that God was transcendent and could not be depicted in art. The iconoclasts feared that Christians praying before icons were worshipping inanimate objects.

On the other hand, the “iconophiles” (literally “lovers of images”), also known as “iconodules” (literally “servants of images”), defended icons, arguing that since Jesus, the Son of God, was born with a visible human body, he could be depicted in images. The iconophiles maintained that rather than worshipping inanimate objects, they honored icons as a means of honoring the holy figures represented in icons.

Imperial and Church authorities in favor of icons gathered at a council in the city of Nicaea in 787 to try to resolve the controversy, but it was not until 843 that the Church definitively affirmed the use of images, ending the Iconoclastic Controversy in what became known as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.” To this day, icons continue to play important roles in the faith and worship of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which is heir to the religious tradition of Byzantium.

Imperial and church authorities affirm the use of images in this Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, c. 1400, Constantinople, tempera on wood, 39 x 31 x 5.3 cm (The British Museum)

In addition to affirming Christian images, the 787 Council of Nicaea II and subsequent 843 Triumph of Orthodoxy also enshrined devotional practices associated with icons. Christians should bow before and kiss icons, light candles and lamps, and burn incense before them. All of these acts of devotion directed at images were intended to pass to the holy figures represented. As a modern analogy, we might consider the ways many people frame and hang photos of loved ones in their homes, sometimes even embracing or kissing such images.

Reading icons

Today, many people identify art with creativity and self-expression. But this was not always the case. Icons were meant to represent historical figures and Christian teaching in a manner that was recognizable and understandable for viewers. Since icons were venerated as a way of showing devotion to the figure represented, understanding who was depicted was particularly important. To achieve this, artists often relied on established artistic conventions.

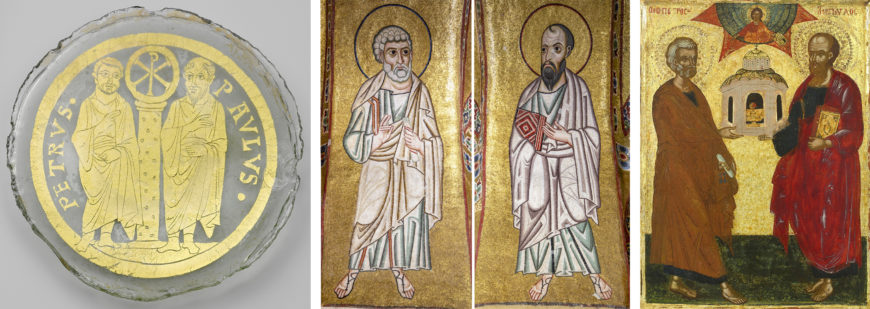

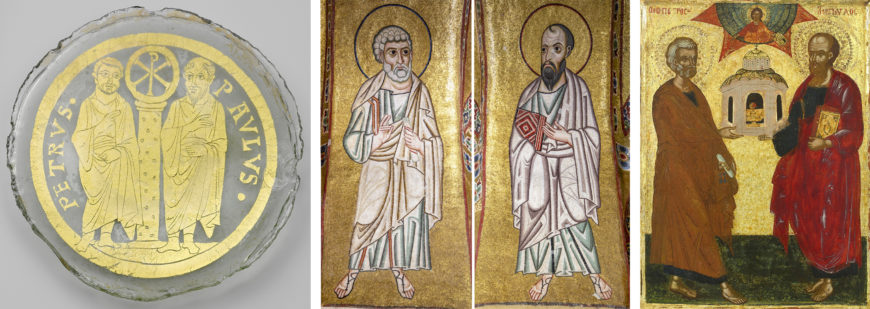

Peter and Paul appear much the same through the centuries. Left: glass bowl base, 4th century, Roman (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); center: mosaics, 11th century, Hosios Loukas Monastery, Greece; right: panel icon, 17th century, Greek (Temple Gallery).

For example, Saints Peter and Paul appear much the same through the centuries: Peter is an old man with white wavy hair and a short beard; Paul has balding, brown hair and a pointy beard. Modern viewers may dismiss such repetition as unoriginal. But for viewers familiar with these conventions, the figures in icons were immediately recognizable, like seeing the faces of old friends.

Saints with their iconographic attributes. Left to right: Evangelist Matthew with Gospel Book (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), the deacon Saint Stephen swinging a censer (The Menil Collection), the healer Saint Panteleimon holding a medicine box (byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), and the martyr Saint Barbara holding a cross (byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). (view annotated image)

Icon with Saint Demetrios, 950–1000, Byzantine, ivory, 19.7 x 12.1 x 1cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Artists also used what art historians call “iconographic attributes” to identify figures. For example, evangelists (authors of the Gospels) often hold Gospel books. Clergy saints wear church vestments and hold liturgical objects, such as censers, which were used by the clergy in church services. Healer saints hold boxes of medicine. Martyrs—saints who had died for their faith—often hold crosses to associate their sacrifice with the death of Christ on the cross.

These attributes helped identify the holy figures represented. But there were no rulebooks governing these conventions, so iconographic attributes were subject to change. It was only in the post-Iconoclastic period, for example, that artists regularly depicted soldier saints in military garb, as seen in this tenth- or eleventh-century ivory icon of Saint Demetrios.

Another way of guaranteeing that viewers recognized the figures in icons was by including texts that labeled the icon’s subjects. Although labels were sporadic before Iconoclasm, they became normative in the post-Iconoclastic era. So, icons of Christ are labeled “IC XC” (the Greek abbreviation for “Jesus Christ”). Icons of the Virgin Mary are labeled “MP ΘY” (the Greek abbreviation for “Mother of God”). And icons of most other holy figures are labeled ὁ ἅγιος (o agios, meaning “saint,” or more literally, “holy”), sometimes abbreviated with as an “Α” within an “Ο” as seen in this this tenth- or eleventh-century ivory icon of Saint Demetrios.

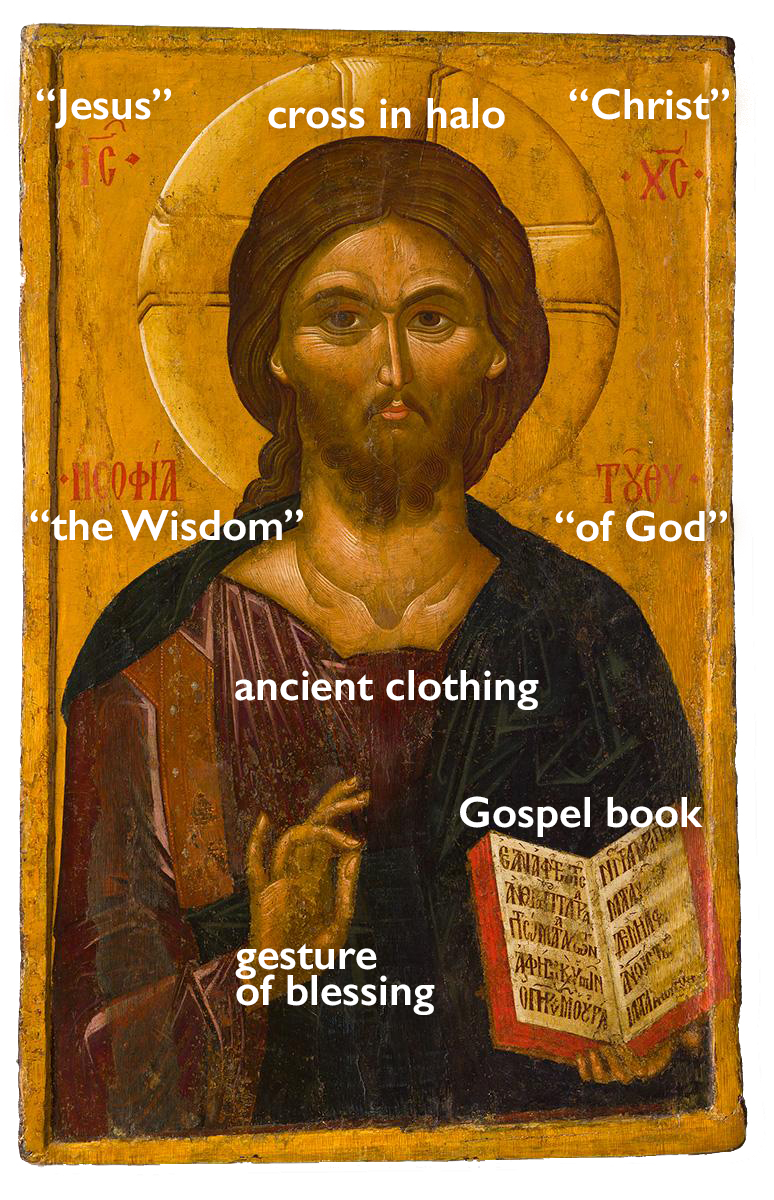

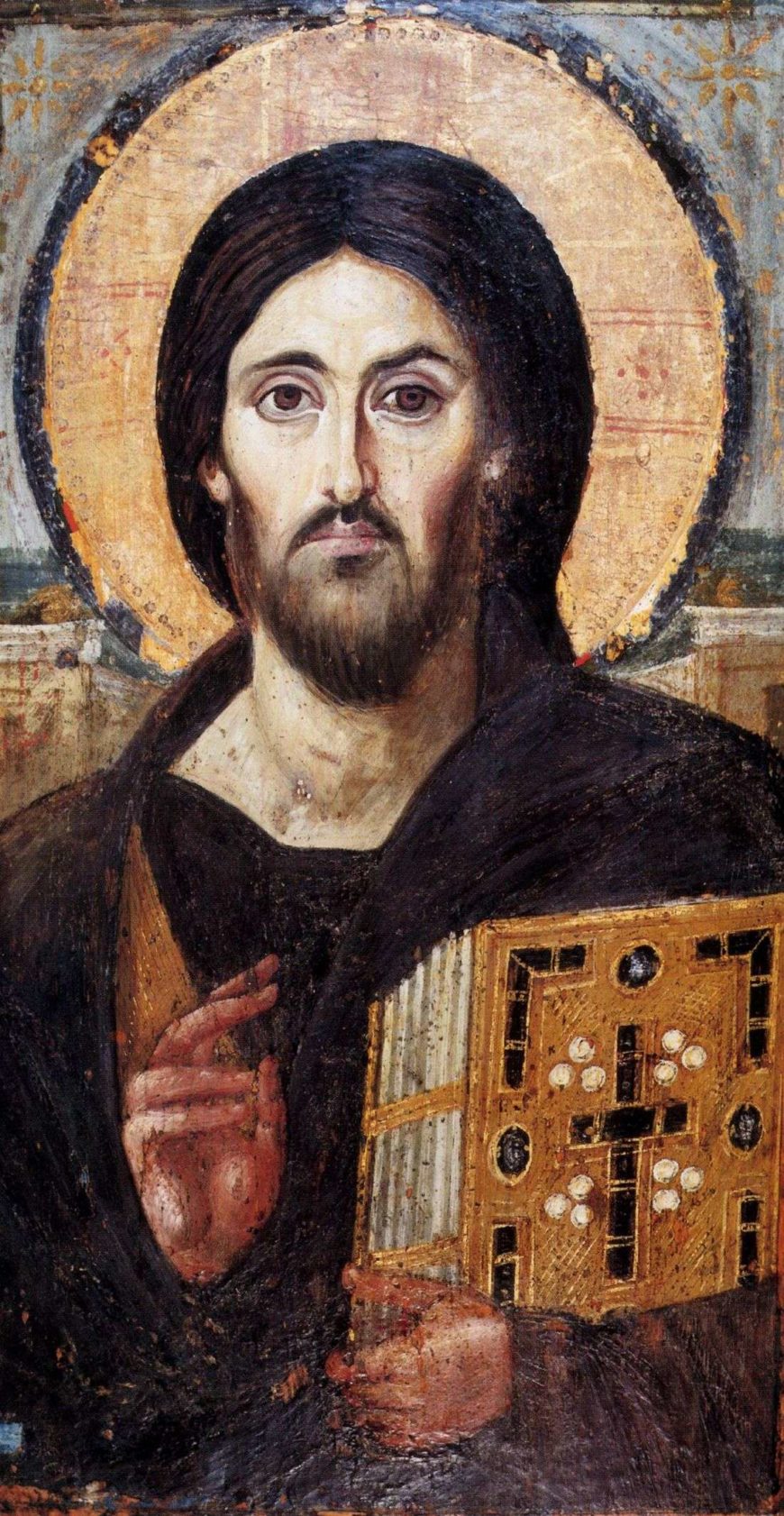

Icon of Christ Pantokrator, late 14th century, Thessaloniki, egg tempera on wood, 157 x 105 x 5 cm (Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki)

Consider how these elements work together in this late-fourteenth-century icon of Christ. Christ appears with his conventional long brown hair and beard. Iconographic attributes describe him further: The artist has sought to portray Christ in clothing from the ancient era in which he lived; Christ holds a Gospel book displaying his own words from Matthew 6:14–15; and there is a cross in Christ’s halo because he was crucified to save the world. Finally, the text identifies this as “Jesus Christ,” and also includes a more particular title: “the Wisdom of God.” Together, all these elements enabled Byzantine viewers to recognize the figure who gazed out and blessed them.

Variety and creativity

But while the use of artistic conventions, attributes, and inscriptions made icons recognizable through the centuries, it would be wrong to suggest that all icons were the same. Icons varied based on the scale and medium in which they were depicted, as well as across periods and regions, where they were often the product of local materials, workshops, and tastes.

Depictions of the Virgin and Child varied widely in icons. Left to right: Enthroned Virgin and Child, 950–1025, Byzantine (The Cleveland Museum of Art); Virgin orans, 13th century, Yaroslavl (byzantologist); Virgin Eleousa, early 14th century, Byzantine (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), Virgin Kykkotissa, 13th–14th century, Cyprus (Byzantine Museum of Saint Ioannis at Kalopanayiotis, Cyprus)

Artists also regularly experimented with new compositions. Depictions of the Virgin and child, among the most popular subjects of Byzantine icons, took numerous forms through the centuries.

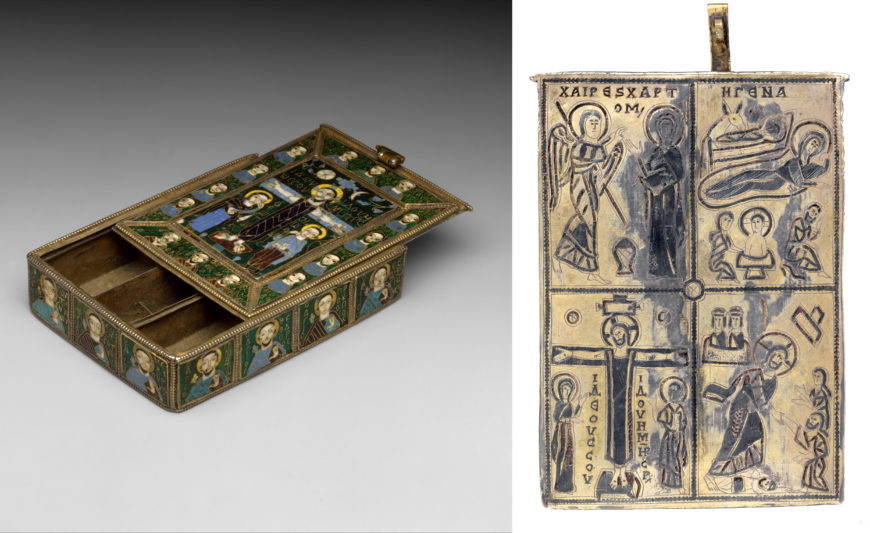

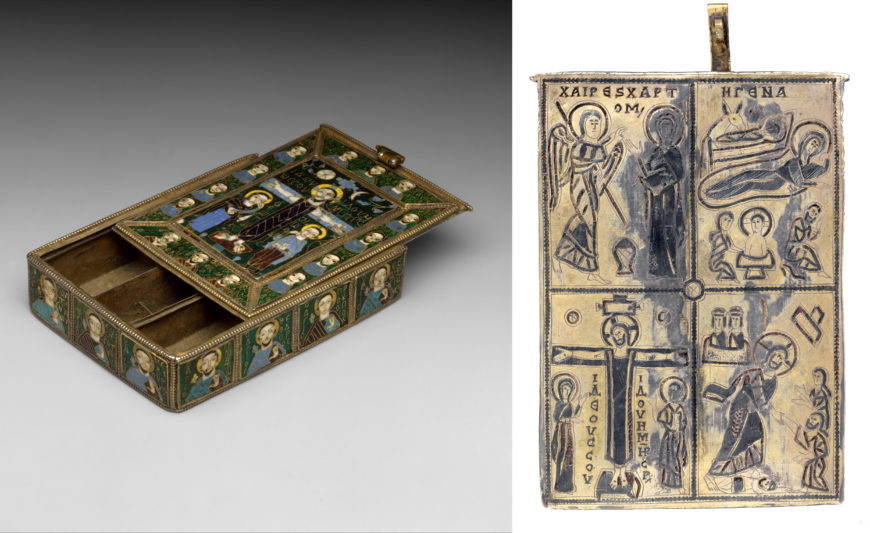

An early example of the Anastasis appears on this reliquary (container for relics) (left), located on the bottom right corner of the inside of the lid (right). The Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke, early 9th century, Constantinople(?), gilded silver, gold, enamel worked in cloisonné, and niello, 2.7 x 10.3 x 7.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). (view annotated image)

Sometimes, artists invented new images that were widely imitated. The Anastasis (Greek for “Resurrection”), which depicted Christ descending into Hades (the underworld) to raise the dead from their tombs, first appeared in the eighth century and has remained a common image in Orthodox churches to this day.

Anastasis fresco, c. 1315–1321, Chora Monastery, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) (view annotated image)

But another example, the unique tenth-century ivory Crucifixion at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which drew imagery from church hymnography to show Christ’s cross impaling a personification of Hades, was apparently one of a kind. No comparable images survive.

Icon with the Crucifixion, mid-10th century, probably made in Constantinople, ivory, 15.1 × 8.9 × 0.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Functions of icons

Icons had a wide range of functions in Byzantium. Their readability enabled them to illustrate Biblical texts, hagiographies, and theological ideas. It was a truism in the middle ages that images functioned as “books for the illiterate.” Before the age of the printing press and inexpensive books, few people owned books, and many could not read. While biblical passages were read aloud in church services, icons offered visual depictions of biblical events that all could see whenever they entered a church.

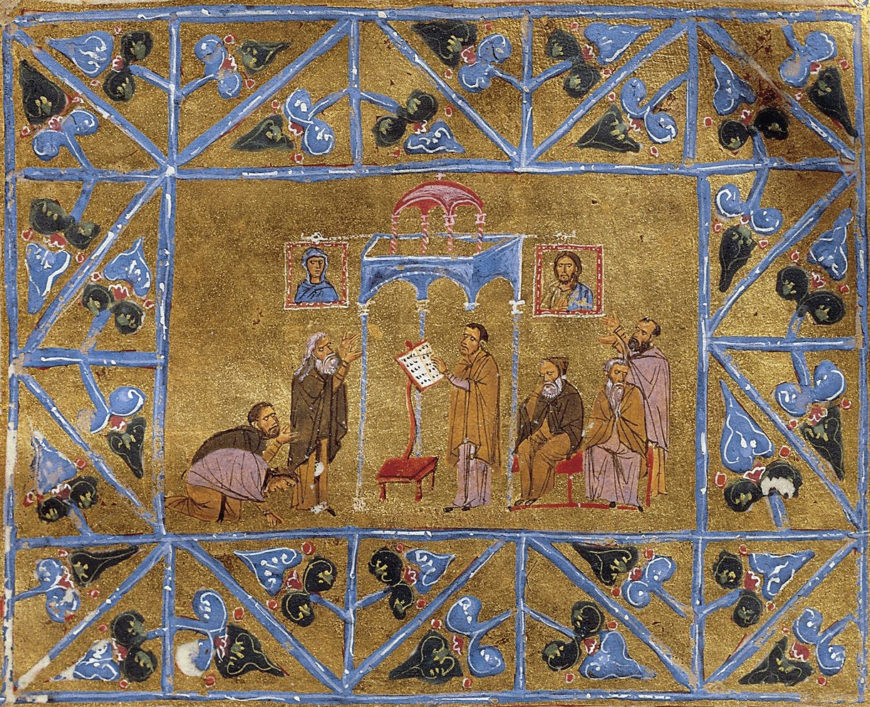

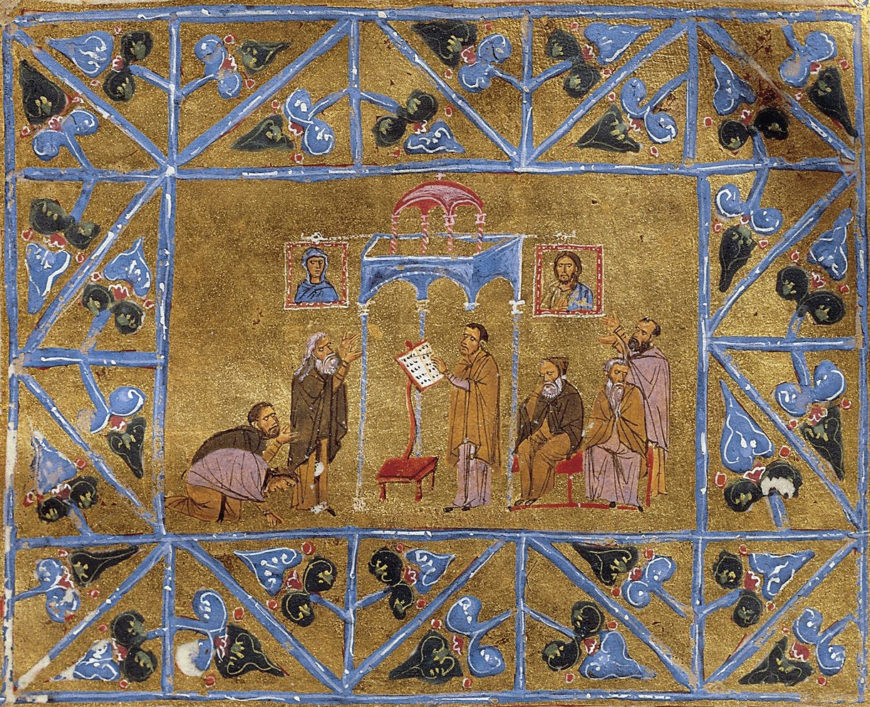

Miniature depicting monks praying with icons in a church, in codex containing the Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus (Sinai cod. 418, fol. 269), 12th century (The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai, Egypt).

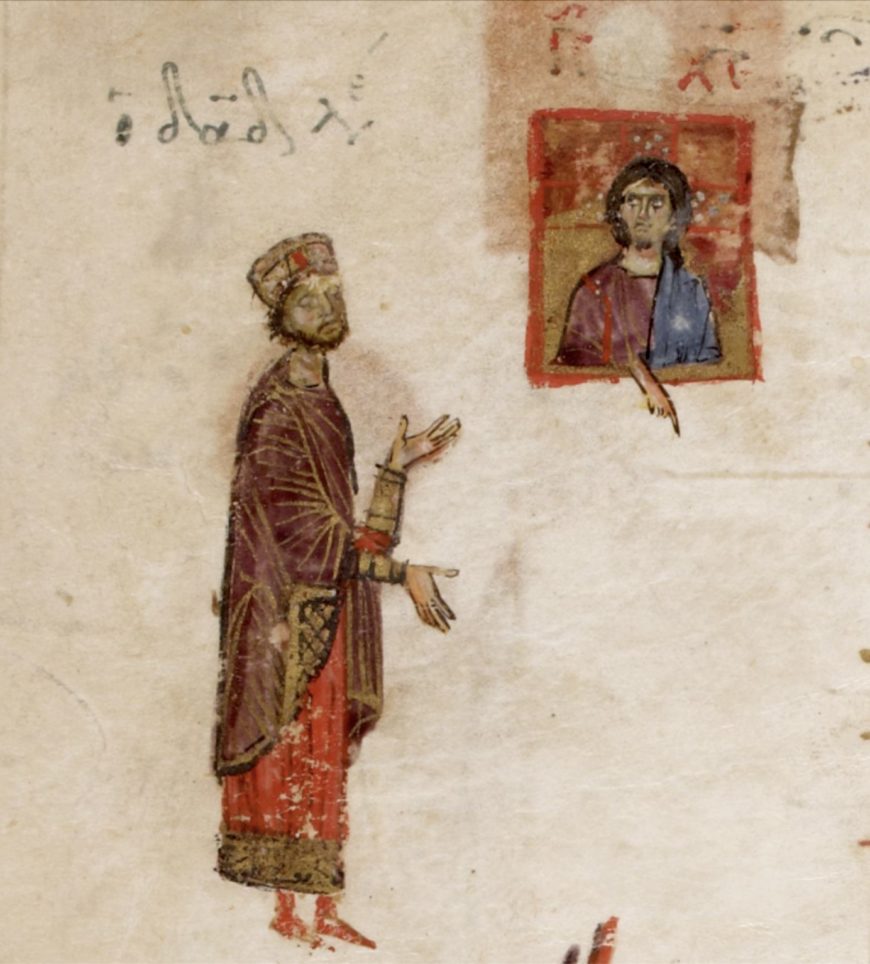

Icons also served as a focus for prayer and devotion, both in church services and in private settings. The frontality of portrait icons facilitated face-to-face encounters between holy figures and worshippers who wished to address the holy figures in prayer. The eleventh-century Theodore Psalter anachronistically imagines such an encounter between King David (from the Hebrew Bible) and a Byzantine icon of Christ.

King David praying before an icon of Christ, miniature in the Theodore Psalter (Add MS 19352, fol. 15v), 1066, Constantinople (The British Library)

In many instances, the saints were believed to work miracles through their icons. Numerous Byzantine texts describe the figures in icons coming alive to defend or heal people. Icons could even be worn as jewelry, and inscriptions suggest that their wearers hoped these wearable icons would protect or heal them.

Fresco depicting the emperor and church officials in a procession with an icon of the Virgin and Child, c. 1380, Markov Manastir, North Macedonia (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Solidus of Justinian II showing Christ on one side (left) and the emperor on the other side (right), 692–95, Constantinople, gold, 4.43 g, 2cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

And in a culture with no notion of separation of church and state, icons frequently blurred the boundaries between religious and political imagery. Icons were carried in public processions, processed around city walls in times of distress, and even carried into battle. A fourteenth-century fresco at Markov Manastir in North Macedonia depicts both the Byzantine emperor and Church officials in procession with an icon of the Virgin and Child. In Hagia Sophia, the great cathedral of the Byzantine capital, mosaics depicted haloed emperors and empresses within the same frame as Christ and the Virgin. Icons of Christ even appeared on Byzantine coins during the reign of Justinian II around the turn of the eighth century, where God and emperor were literally on two sides of the same coin.

Mosaic of Christ (center) with emperor Constantine IX (left) and empress Zoe (right), 1042–1055, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Adorning icons

Increasingly in the Late Byzantine periods, wealthy patrons affixed thin pieces of precious metal, or “revetments,” to icons as a way to honor the holy figures depicted. These metallic adornments often included ornamental motifs, additional icons, and sometimes even images of the patrons and poetic inscriptions known as epigrams, which recorded the donor’s prayers.

Icon of the Virgin and Child, silver revetment: late 13th–early 14th century, Constantinople, tempera painting: 15th century, Moscow (Tretyakov Gallery, photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An icon in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow preserves silver revetment from thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Constantinople, although a later, fifteenth-century painting has replaced the original, which was likely lost or damaged. This revetment covers much of the wooden surface with a swirling filigree pattern, and smaller icons of various saints populate the icon’s frame. Two full-length portraits of the Byzantine donors appear in the lower corners of the frame.

Triptych with the Mandylion, 1637, Moscow, Silver, partly gilt, niello, enamel, sapphires, rubies, spinels, pearls, leather, silk velvet, oil paint, gesso, linen, mica, pig-skin, woods: Tilia cordata (basswood or linden), white oak, 68.6 x 90.8 x 12.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

After the fall of Byzantium to the Ottomans in 1453, the tradition of affixing precious materials to icons endured in places like Russia, where the icon cover was referred to as an oklad or riza. Russian oklads were often elaborate, covering the entire icon except for the face and hands of the holy figures represented, as seen with a seventeenth-century icon depicting the face of Christ at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The modern “discovery” of icons

Use and the passage of time often left icons worn out or damaged. Icon varnish tended to darken with age, obscuring the icon’s image. In an age when modern restoration techniques did not yet exist, artists often painted directly over the darkened images so that an icon could be seen and used once again.

Left: 1904 photograph of Rublev’s Trinity before restorations showing the oklad and later overpainting; right: current state of Rublev’s, Trinity, c. 1410 or 1425–27, tempera on wood 142 x 114 cm (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; photos: Wikipedia)

Detail showing the scarred surface of Andrei Rublev’s Trinity, c. 1410, tempera on wood 142 x 114 cm (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

But at the turn of the twentieth century, new restoration techniques enabled conservators to uncover the original layers of many old, overpainted icons. In Russia, countless icons were stripped of oklads, darkened varnish, and layers of overpainting to reveal their original images. Such was the case with the fifteenth-century icon of the Trinity attributed to Andrew Rublev, restored in 1904 and again in 1918. While the restoration of Rublev’s Trinity revealed the brilliant colors and balanced composition of the original image, it also erased the many acts of devotion and overpainting that occurred through centuries, to which nail holes across the scarred surface of the image still attest. Walking through museums in Russia, one finds that many icons bear similar nail holes that once affixed oklads to the icons’ surfaces.

Many of Russia’s newly-restored icons were transferred from churches and exhibited in museums, which drastically changed the circumstances of their viewing. Such newly cleaned icons offered art historians valuable insights about the past and inspired modern artists in the present. After viewing an exhibition with icons in Russia in 1911, Henri Matisse famously commented: “French artists should come to study in Russia: Italy offers less in this field.”

Viewing icons then and now

Both the restoration of icons and their subsequent interpretation in the twentieth century were strongly influenced by modern tastes and theories of art. Today, the earliest painted image is prized, while the oklad is often dismissed as an ornamental addition that is foreign to the nature of the painted icon. Drawing parallels with modern art, art historians and critics like Clement Greenberg described icons as non-naturalistic, and many art historians have interpreted this aspect of icons as symbolizing spirituality and the figures in icons as distant from viewers.

More recently though, art historians have noted that the Byzantines consistently described the sacred figures in icons as accurate and lifelike.

Apse mosaic depicting the Virgin and Child, dedicated 867, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Preaching in 867 about a new mosaic installed in the apse of Hagia Sophia following the Triumph of Orthodoxy over Iconoclasm, patriarch Photios, the leader of the Byzantine Church, stated:

With such exactitude has the art of painting, which is a reflection of inspiration from above, set up a lifelike imitation…You might think her not incapable of speaking, even if one were to ask her, “How didst thou give birth and remainest a virgin?” To such an extent have the lips been made flesh by the colors…Photios, Homily 17

Such texts remind us that the ways we view artworks are often highly contingent on our own cultural contexts.

Additional resources

Holy Image, Hallowed Ground

Holy Image, Hallowed Ground. URL: https://vimeo.com/9708525

“Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium,” The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Icons,” National Gallery of Art

Cite this page as: Dr. Evan Freeman, “Icons, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, December 3, 2020, accessed October 31, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/icons-introduction/.