87 Plot

The chapter on Characterization defines narrative as the semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause. But what precisely are events? And what constitutes a sequence of events? Does it matter whether the connecting thread that makes up that sequence is time or cause, or perhaps both? These are some of the essential questions that we will try to untangle in this chapter.

To be sure, they are not easy questions to answer. Narratology has struggled with them for some time and has come up with a range of terms and theories that sometimes bring more confusion than clarity. We will not delve here into the complexities of theory or the endless terminological discussions that have plagued the field.[1] But we do need to introduce the key conceptual distinction between story and plot, which has been key to achieve a better understanding of the structure and function of narratives.

The concept of plot dates all the way back to Aristotle (Fig. 1), who defined mythos as the arrangement or “organization of events” and argued that it was the most important element of storytelling.[2] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Russian formalists recovered this concept and established a key distinction between the “story” (fabula) and the “plot” (szujet) of a narrative.[3] In the English language, the translation of these terms has created and continues to create a considerable amount of confusion, derived from the fact that “story” is used at the same time as a generic term for narrative and as a technical term in narratology. For the purpose of this textbook, we will obviate these problems and simply integrate this important distinction into the semiotic model of narrative presented elsewhere.

First, we will discuss more precisely the distinction between story and plot, clarifying what we understand by an “event” and the different ways in which the events of a narrative can be connected. Then we will look at the mechanisms of emplotment, the specific operations that can be applied to a story when arranging it into a plot. By arranging events in a meaningful and coherent structure that has a beginning, a middle, and an end, these mechanisms can result in many kinds of plot. We will look at a few of these, which are quite common in prose fiction. Most of these plots are motivated by a conflict, which can be external or internal, and lead to some form of resolution. We will look at this ‘story as war’ analogy and present a five-stage general structure that can be found in many narrative plots. Finally, we will discuss two important mechanisms of emplotment at the micro level, suspense and surprise, which are often used by writers to engage readers and hook them to the narrative.

The Thread of Narrative

As we pointed out earlier, the story is the message that the narrator communicates to the narratee in a narrative. In this sense, it refers to a set of events happening in an alternative world, which we call the storyworld. We can define narrative events as changes of state occurring in the storyworld.[4] Such a world could be an accurate reflection of the lifeworld of the writer and his readers or an imaginary world that has never actually existed. Whatever the truthfulness of this storyworld, the events of the story are supposed to have happened in it. These events can be actions undertaken by characters, but they can simply be situations, incidents, experiences, or things that happen to them or to their environment.

Let us imagine a simplified story to clarify these ideas. In this story, we only have five events: (1) George rode to the lake, (2) George slew the dragon, (3) George rescued the princess, (4) George and the princess rode away from the lake, and (5) George and the princess got married in the castle. We can display these events as marks in a horizontal arrow representing time (see Fig. 2).

This is an arrangement of the events according to their succession in time. And this is what we call the story. Of course, the events in this story are also implicitly connected by cause (for example, event three is the consequence of event two). But our arrangement does not stress those connections. It simply reflects when the events happened in relation to each other (event two comes after event one, event three after event two, etc.).

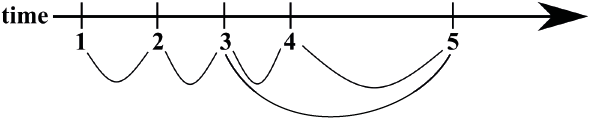

It is unlikely, however, that the narrator will arrange the events of the story in such a simple fashion when telling it to the narratee. One thing the narrator could do, for example, is to stress the causal connections between the events: (1) George rode to the lake looking for the princess, (2) George slew the dragon in order to rescue the princess, (3) After killing the dragon, George rescued the princess, (4) George and the princess rode away from the lake to find safety in her castle, and (5) The princess married George to thank him for rescuing her from the dragon. We can display the causal connections with curved lines (see Fig. 3).

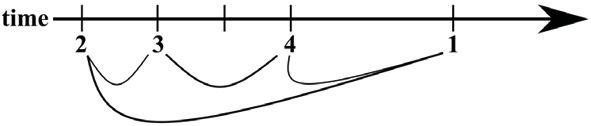

Another thing that the narrator could do is to present the events in a different order, without necessarily following their sequence in time. For example, he could begin by telling the narratee about (1) the wedding between George and the princess, and only then go on to explain why the princess accepted George as her husband by telling how (2) George rode to the lake looking for the princess, (3) slew the dragon, and (4) escaped to safety with the princess. In this case, we would need to alter the representation of the sequence of events in the narrative (see Fig. 4).

We call the actual arrangement of the sequence of events by the narrator of the story the “plot.” Emplotment can involve simple modifications to the story, for example when the narrator tells the story “as it happened.” But plots can also be much more complex and modify substantially the order of events, their duration, or the connections between them. As the novelist E. M. Forster explained,

We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died, and then the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief,’ is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: ‘The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.’ This is a plot with a mystery in it, a form capable of high development. It suspends the time-sequence, it moves as far away from the story as its limitations will allow. Consider the death of the queen. If it is in a story we say, “and then?” If it is in a plot we ask, “why?”[5]

Emplotment

Stories can be arranged into many kinds of plot. And there can never be a story without a plot, even if the plot is simply the presentation of events in their chronological succession, which would make the plot indistinguishable from the story. In fact, the story is only an abstraction, which is never accessed directly as such (either by the reader, the implied reader, or the narratee). What we read in a narrative is always a particular emplotment of the story.

For instance, the story of Saint George and the dragon, which we have simplified as an example in the previous section, has been told in different ways (Fig. 5). The succession of events is not the same in all these retellings. The narrator might begin the tale with the apparition of the plague-bearing dragon that poisons the lake and forces the kingdom to sacrifice their children to appease the beast. But the narrator might also begin with George riding near the lake and hearing the cries of distress from the princess. Some retellings invest much time recreating the conversation between George and the princess at that moment, while others move directly to the fight between George and the dragon. In some retellings of the story, George marries the princess at the end. But in others the marriage, whether it happened or not, is left out of the tale. All these versions stem from different decisions on the part of the authors and result in different plots of the same story. We call emplotment the process of arranging the events of the story into a narrative message communicated by the narrator to the narratee.

Emplotment involves five basic operations:[6]

- Order: The sequence of events in the plot may or may not follow a strict chronological succession. Emplotment can modify the order in which the events are presented by the narrator, for example by beginning at some point in the middle of the story (in medias res) and then jumping back to events that happened earlier (flashback) or later (flashforward).

- Duration: The duration of the events in the plot may or may not reflect the actual duration of those events in the story. Emplotment can modify the duration of the events presented by the narrator, for example by compressing time (e.g. telling fifty years in the life of a character in one paragraph) or expanding time (e.g. describing a kiss that lasted for one second in ten pages).

- Frequency: The number of times that events are repeated in a plot may or may not reflect the number of times that those events occurred in the story. Emplotment can modify the frequency of the events presented by the narrator, for example by repeating the same event several times in the plot (repetition, e.g. telling the same murder from different perspectives) or collapsing several events of similar nature into a single event (iteration, e.g. telling the protagonist’s daily work routine as one exemplary set of events happening on any given day).

- Connection: The connections between the events in the plot may or may not reflect the actual connections between the events in the story. Emplotment can modify the meaning of the events presented by the narrator through the establishment of explicit or implicit causal connections between them. Ultimately, of course, it will depend on the reader’s interpretation to determine which causal connections need to be retained from the narrative beyond the basic chronological succession of events.

- Relevance: Similarly, the information about the events provided in the plot may or may not exhaust the actual information that is relevant about those events in the story. Emplotment can modify the meaning of the events presented by the narrator by providing or withholding information related to those events. Once again, the reader will have to interpret which of the pieces of information presented are relevant and fill in the gaps left by the narrator.

Not every plot applies all these operations to the story. As we have seen, it is even possible to have a plot that does not modify or add causality to the chronological succession of events. These operations are simply theoretical possibilities, which writers may or may not use to arrange the events of the story told by the narrator.

Beginnings, Middles, and Ends

As pointed out by Aristotle in his Poetics, plots are generally arranged to have a beginning, a middle, and an end.[7] But Aristotle was not simply stating the obvious fact that plots start at some point, extend during some time, and finish at another point. What he meant is that plots have an internal coherence that connects beginnings with endings through a meaningful and purposeful development. Unlike events in life, which simply happen, without any coherence or purpose, emplotted events are meaningfully connected to form a coherent whole. In real life, there is no such thing as a ‘beginning’ or an ‘ending,’ unless someone turns those events into a plot. Even a person’s birth or death are unconnected events, without any meaning or significance in the general scheme of things. We need to emplot those two events, together with whatever happens in the middle, into some kind of narrative (e.g. “he was born in 1903, worked as an accountant during most of his life, and died peacefully in his own bed aged 82”) before they become a beginning and an end, the opening and closure of a biographical plot.

Biography, the narrative of a person’s life, is a type of plot that seems quite natural to us, accustomed as we are to see ourselves and other individuals as coherent and meaningful entities. It is not surprising, therefore, that biographical plots have often been used by fiction writers to arrange their stories. For example, Daniel Defoe’s classic novel Robinson Crusoe (Fig. 6) begins with the eponymous character’s birth and goes on to narrate his life adventures, including the time he spent as a castaway on a remote desert island. Although the novel ends somewhere in the middle of Robinson’s life, while promising a second part to the story, the organizing principle of the plot is clearly biographical.

But biography is only one of the many kinds of plot that we find in narrative. Since Aristotle, many typologies of plot (sometimes called masterplots) have been proposed.[8] While the best of these typologies might be able to capture certain recurrent aspects of emplotment, they can never embrace all possible narrative plots. Provided we take these typologies as an orientation, and avoid turning them into rigid and normative taxonomies, they can help us to better understand the various ways in which narrators can arrange the events of the plot.

For example, the following are seven kinds of plot that we often find in popular novels and short stories, described in terms of beginnings, middles, and ends:[9]

- Overcoming the monster: It begins with the protagonist setting out to defeat an evil (or threatening) force; it narrates the fight between the hero and this monster; and it ends with the defeat of the monster. For example, in ‘Hansel and Gretel’ (Fig. 7), a German fairy tale recorded by the Brothers Grimm, two children try to escape from the forest house of a witch who has kidnapped them and intends to eat them.

- From rags to riches: It begins with a poor protagonist; it narrates how she goes on to acquire wealth and power, but then loses everything again (or loses and regains it once more); and it ends with her becoming wiser thanks to the experience. An example of this kind of plot is the Middle Eastern folk tale ‘Aladdin and the Magic Lamp,’ often included in One Thousand and One Nights, which tells the adventures of a young and poor orphan who becomes rich and powerful with the help of a genie.

- The quest: It begins with the protagonist (and maybe some companions) setting out to obtain an important object; it narrates the many obstacles that they must face; and it ends with the successful completion of the quest. J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit is a famous example of this kind of plot, where the hobbit Bilbo and his companions set out on a dangerous quest to recover the treasure guarded by a dragon.

- Voyage and return: It begins with the protagonist departing her home for a strange land; it narrates the threats and adventures that she needs to overcome; and it ends with her return home enriched by the experience. Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where the protagonist suddenly finds herself in a strange underground world, is a well-known example of this kind of plot.

- Comedy: It begins with a light and humorous protagonist; it narrates the various circumstances and problems that she must overcome; and it ends with the happy resolution of these circumstances or problems. An example of a novel with this kind of plot is Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, where the Dashwood sisters end up happily married after all sorts of complications.

- Tragedy: It begins with a protagonist who is affected by some sort of mistake or flaw that is the origin of a certain conflict; it narrates how he tries to overcome this conflict; and it ends with his failure to do so, and perhaps with the recognition of his mistake or flaw. A modern example of this kind of plot is Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel Lolita, where the sexual obsession of an aged literature professor for a twelve-year-old girl leads him to commit successive transgressions until he dies in prison.

- Rebirth: It begins with the protagonist living her normal life; it narrates how certain circumstances (normally adverse ones) force her to change her life; and it ends with her transformation into a new person capable of overcoming those circumstances. A well-known example of this kind of plot is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, where old Scrooge, a miser who is unable to partake in Christmas celebrations, becomes a kinder person after receiving the visit of several ghosts.

Conflict and Resolution

In the masterplots described above, the main characters (or protagonists) are motivated to act by some conflict. Whether this conflict is external (e.g. a monster or a circumstance that poses a threat) or internal (e.g. a mistake or a flaw in one’s character), the kernel of the plot seems to be the need to overcome this conflict and find some form of resolution.

Ancient Greeks referred to conflict as agon. The importance of this concept for narrative can be grasped by the fact that we still call the leading character of a story its ‘protagonist’ (meaning, one who fights for something or someone). We also call the main enemy of this character, whether it is another character or some natural or supernatural force, the ‘antagonist’ (meaning, one who fights against something or someone).

In the Poetics, Aristotle claims that plots can be divided into those where the protagonist succeeds in overcoming the conflict (goes from misfortune to fortune, as in comedy) and those where the protagonist falls victim to the conflict (goes from fortune to misfortune, as in tragedy).[10] In both cases, there is a reversal of fortune (peripeteia) and some form of resolution, which may or may not involve a recognition or gain in knowledge for the protagonist (anagnorisis).[11] For example, in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (Fig. 2.8), King Oedipus faces a devastating plague in his city of Thebes (conflict) and seeks to find the person responsible for spreading the infection. A carefully crafted series of events lead Oedipus to discover (reversal of fortune and recognition) that the culprit is none other than himself, having unknowingly killed his father and married his own mother many years earlier. At the end, after his mother/wife commits suicide, Oedipus blinds himself and is banished from Thebes.

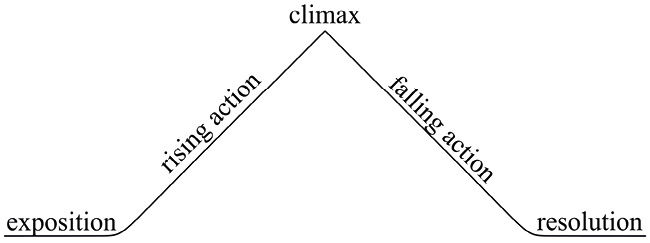

Aristotle’s description of tragic conflict and resolution, as exemplified in Oedipus Rex, has been tremendously influential throughout history and has resulted in the view that all plots are essentially motivated by a conflict and move forward to close or resolve this conflict. This idea has been formalized in the five stages of Freytag’s pyramid (Fig. 9), which was originally conceived to describe the conventional emplotment of dramatic plays in five acts,[12] but is often applied to narrative plots as well:

- Exposition: In this initial stage, the environments and the characters, particularly the protagonist, are introduced. There is no conflict yet, but we might get indications about the conflicting goals of the characters and the motives that will drive the plot.

- Rising action: At some point, the (external or internal) conflict is revealed and provokes a series of events (confrontations, reversals, adventures, etc.) that move the plot forward and always towards a higher degree of intensity. In novels and short stories, this stage tends to be the longest and includes most of the vicissitudes of the plot.

- Climax: This is the point where the rising action achieves its maximum level of intensity and the conflict reaches the decisive confrontation. It is also a turning point, because from here on the conflict can only move towards the final resolution. The climax is not always an external event, such as a battle between the protagonist and the antagonist. It can also be a more subtle reversal of fortune, for example the recognition of one’s own guilt, which decides the outcome of the conflict.

- Falling action: The events that follow the climax might still be motivated by the conflict, but they tend to wane in intensity and progressively lead to some form of resolution. Characters settle their confrontations, solve or abandon their problems, overcome or submit to existing threats and enemies. In one way or another, the climax has already decided the outcome of the conflict and the falling action needs to bring the situation back to an equilibrium. In prose fiction, this stage is often much shorter and does not include as many events as the rising action.

- Resolution: At the end, the conflict has been solved, either because the protagonist or the antagonist have won, or because they have found some way to solve their disagreements, or simply because they have exhausted their capacity to continue fighting. In the resolution stage, we might be shown what the characters do after everything is settled or find answers for the outstanding questions. In prose fiction, this stage often tries to provide a sense of closure.

This model, based on a ‘story as war’ analogy, is often presented as the only way to emplot a story. While it is true that many popular fiction stories follow this pattern in one way or another, there are other plots, particularly in modern and contemporary literature, that depart quite significantly from the dynamic of conflict and resolution that author Ursula K. Le Guin described as the ‘gladiatorial view of fiction’:

People are cross-grained, aggressive, and full of trouble, the storytellers tell us; people fight themselves and one another, and their stories are full of their struggles. But to say that that is the story is to use one aspect of existence, conflict, to subsume all other aspects, many of which it does not include and does not comprehend.[13]

While perhaps not as common, there are alternative models of emplotment that reflect these other aspects of existence. One such model could be ‘story as birth,’ where the plot is motivated, not by conflict, but by the desire and the struggle to arise and grow, as in the experience of many living things.[14] A novel that seems to follow this model of plot is Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. While this story does not lack elements of conflict or tension, its plot is mainly arranged by the emergence of emotions in the subjective experience of the characters, for example through the creative process that Lily Briscoe undergoes before she is able to complete her painting at the end of the novel.

Yet another model, somehow related to the organic analogy of the previous one, but also incorporating Aristotle’s theory of recognition (anagnorisis)[15] and James Joyce’s conception of epiphany,[16] is ‘story as illumination,’ where the protagonist moves from darkness to light, from ignorance to knowledge, without the need to engage in any form of conflict. In Joyce’s collection of short stories, Dubliners, for example, characters experience sudden moments of illumination (epiphany) that give them a new understanding of their world and produce a meaningful change in their lives.

Even when modern prose fiction follows the war analogy and uses conflict to motivate the plot, it often presents these conflicts as fundamentally unresolvable. Many authors see the classic idea of an ending that brings resolution to the conflict as unrealistic and only fit for entertainment. Thus, open and ambiguous endings are quite common in serious modern literature, which tends to avoid providing the reader with an artificial sense of closure (‘and they lived happily ever after’). Even in these narratives, however, there is often some form of ending. While they might leave many questions unanswered at the end, it is precisely this questioning that provides meaning and gives coherence to the whole plot.

Suspense and Surprise

So far, we have been speaking of plots at a macro level. But there are two important mechanisms of emplotment, suspense and surprise, which operate at the micro level, particularly as the events move through the rising action towards the climax of the plot (provided that the plot follows Freytag’s pyramid or a similar structure). These mechanisms cross over in some ways from story to discourse, but we need to discuss them here to complete our presentation of plot.

Suspense is a phenomenon that derives from the arrangement of events in the plot, but which cannot exist without the reader. It arises from the gap between what the reader knows from the previous events in the plot and what she anticipates is going to happen next.[17] In a way, it stems from the curiosity of the reader asking herself ‘and then what?’ as the plot unfolds.

Suspense can be heightened when the reader knows more than the characters, or even the narrator. For example, the reader might know that the killer is hiding in the bedroom of the detective’s girlfriend, as he walks unwittingly back home after leaving her at the door of her apartment.

But suspense can be created simply by arranging the events in the plot in a way that ignites the curiosity of the reader. For example, the reader, as well as the detective and his girlfriend, might know that there is a killer on the loose. Certain events in the plot might indicate that the killer is moving on to murder the detective’s girlfriend (a cigarette butt found in her apartment, a strange midnight call, etc.). The anticipation of future events through hints given earlier in the plot is called foreshadowing. Using foreshadowing is generally enough to create suspense, and it is a common technique in some genres, such as mystery and horror fiction. When the event foreshadowed never actually happens, it is called a red herring, a technique that is sometimes employed to mislead and surprise readers.

While suspense depends on the reader’s knowledge (or suspicion) of events to come, surprise is an effect of the reader’s ignorance.[18] As the plot unfolds, the reader anticipates future events based on what she already knows. If something unexpected happens, that is a surprise. When they affect crucial kernels in the plot or alter the situation of the main characters, surprises are the kind of twists that make readers gasp and experience the thrill of unforeseen revelation. For example, if the reader suddenly discovers that the killer is actually the detective’s girlfriend, who has been preparing her alibi before moving on to murder the detective, the whole plot takes a surprising new direction.

Suspense and surprise can work together in the plot to great effect. By keeping the reader always alert, not knowing whether the next event will be the confirmation of a suspenseful anticipation or an unexpected twist, emplotment can create the kind of narrative tension that hooks readers to the book and compels them to keep turning the pages.

Summary

- Story is the arrangement of events according to their sequence in time, while plot is the arrangement of the events by the narrator when telling them to the narratee. In addition to the temporal connection, events in the plot generally have a causal connection.

- Emplotment is the arrangement of the events of the story by modifying their order, duration, frequency, connection, or relevance, in order to make a plot.

- Plots have an internal coherence that connects beginnings with ends through a meaningful and purposeful development.

- While there are various ways to connect beginnings with ends, emplotment is often motivated by a fundamental conflict or tension that moves the plot through the stages of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

- Emplotment can engage the reader by creating anticipation about future events through suspense and foreshadowing, while at the same time disproving the reader’s expectations through surprise.

References

Aristotle, Poetics, trans. by Malcolm Heath (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1996).

Booker, Christopher, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories (London, UK: Continuum, 2004).

Bridgeman, Teresa, ‘Time and Space,’ in The Cambridge Companion to Narrative, ed. by David Herman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 52–65, https://doi.org/10.1017/ccol0521856965

Burroway, Janet, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226616728.001.0001

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin, Reading Narrative Fiction (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1993).

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

Forster, E. M., Aspects of the Novel (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985).

Freytag, Gustav, Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, trans. by Elias J MacEvan (Charleston, SC: Bibliobazaar, 2009).

Genette, Gérard, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990).

Hendry, Irene, ‘Joyce’s Epiphanies,’ The Sewanee Review, 54:3 (1946), 449–67.

Herman, David, ‘Events and Event-Types,’ in Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, ed. by David Herman, Manfred Jahn, and Marie-Laure Ryan (London, UK: Routledge, 2005), pp. 151–52, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203932896

Hühn, Peter, ed., Handbook of Narratology (New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2009), https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110316469

Sklovskij, Viktor Borisovic, Theory of Prose (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991).

- See Handbook of Narratology, ed. by Peter Hühn (New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2009), https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110316469 ↵

- Aristotle, Poetics, trans. by Malcolm Heath (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1996), p. 11. ↵

- Viktor Borisovic Sklovskij, Theory of Prose (Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1991). ↵

- David Herman, ‘Events and Event-Types’, in Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, ed. by David Herman, Manfred Jahn, and Marie-Laure Ryan (London, UK: Routledge, 2005), pp. 151–52, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203932896 ↵

- E. M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985), p. 86. ↵

- Based on Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990). ↵

- Aristotle, pp. 13–14. ↵

- See Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000). ↵

- Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004). ↵

- Aristotle, pp. 8–9. ↵

- Aristotle, pp. 18–19. ↵

- Gustav Freytag, Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, trans. by Elias J MacEvan (Charleston, SC: Bibliobazaar, 2009). ↵

- Quoted in Janet Burroway, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), p. 133, https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226616728.001.0001 ↵

- Burroway, p. 134. ↵

- Aristotle, pp. 18–19. ↵

- Irene Hendry, ‘Joyce’s Epiphanies,’ The Sewanee Review, 54:3 (1946), 449–67. ↵

- Teresa Bridgeman, ‘Time and Space,’ in The Cambridge Companion to Narrative, ed. by David Herman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 52–65, https://doi.org/10.1017/ccol0521856965 ↵

- Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Reading Narrative Fiction (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1993), p. 21. ↵