70 Mary Rowlandson and Captivity Narratives

Joel Gladd

In 2016, Netflix released a mystery drama series created and produced by Brit Marling, title The OA. The series is about a woman who returns to a community after having been missing for several years. She has mysterious scars and gaps in her memory.

What does this show have to do with early American literature?

Many contemporary shows, movies, and other cultural artifacts are based on abductions. The protagonist usually has trauma and is unable to recall what occurred accurately. In the case of The OA, it’s especially difficult to separate fact from fiction.

These modern narratives–and their explicit blending of fact and fiction–participate in a long tradition that reaches back to the early modern period: the captivity narrative.

Captivity Narratives: Definition and Conventions

In his excellent chapter, “Israel in Babylon: The Archetype of the Captivity Narratives (1682-1700),” Richard Slotkin summarizes what readers can usually expect from these captivity narratives:

As the quote above from Richard Slotkin suggests, the captivity narrative genre mapped the trope of exile and redemption onto New World encounters with native tribes. According to “Early American Captivity Narratives,” the basic pattern is this:

- Separation: attack and capture

- Torment: ordeals of physical & mental suffering

- Transformation

That pattern maps closely to Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey: Departure/Separation, Initiation/Ordeals, Return/Transformation. This crossover between the basic structure of most captivity narratives and the hero’s journey more generally is why Campbell and others refer to the journey as a “monomyth”–it tends to inform many cultural myths, legends, and narratives. It helps tell a story.

What’s distinctive about an early modern captivity narrative, however, is that it tends to also include the following:

- Abruptly brought from state of protected innocence into confrontation with evil.

- Forced existence in alien society.

- Unable to submit or resist.

- Yearns for freedom, yet fears perils of escape.

- Struggle between assimilation and maintaining a separate cultural identity.

- Condition of captive parallels suffering of all lowly and oppressed.

- Growth in moral and spiritual strength.

- Deliverance.

What’s important to recognize from the pattern and basic conventions identified above is that these elements provide structure for the personal narrative. The scaffolding allows the story to have a clear arc–towards deliverance and redemption.

One of the earliest captivity narratives was Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s La relación, an account of his experiences with the Navaez expedition after being wrecked on Galveston Island in November 1528. De Vaca’s narrative is enormously complex, but it helped establish a basic framework for the captivity narrative in the early colonial period.

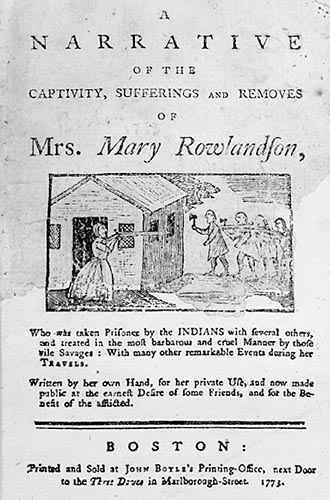

The next influential example was Mary Rowlandson’s The Sovereignty and Goodness of God from 1682[2] which has many similarities with de Vaca (especially being captured by the natives and later being freed), but relies heavily on Puritan typology. Rowlandson’s captivity narrative was not only popular during the 17th-century, as the first publication by a woman from the Americas. It also experienced renewed popularity during the Revolutionary era. Her text (along with one by John Williams) was reprinted “at least nine times between 1770 and 1776.” When Rowlandson was reprinted during the Revolutionary era, the frontispiece was transformed to make her narrative seem more relevant (Fig. 1).

In the reprint edition above, Rowlandson’s captives are represented as British soldiers. By replacing the natives with the British, Revolutionary era publishers (John Boyle) transformed the captivity narrative into an allegory of the colonial-British crown relations, rather than the Puritan-native relations.

Repurposing Rowlandson for Revolution: Greg Sieminski’s “The Puritan Captivity Narrative and the Politics of the American Revolution” explains how this transformation represented a broader trend during the eighteenth century:

It is widely agreed that the captivity narrative underwent a significant change in the eighteenth century. Authors of the earliest narratives, like Rowlandson and Williams, interpreted their captivity as a form of divine testing in which their rejection of Indian culture was equivalent to resisting a satanic temptation in the wilderness. However, in the hundred years following the publication of the first captivity narrative in 1682, as the genre spread beyond New England and as the claims of Puritanism lost their force, the narratives became increasingly secular and eventually gave expression to a potent cultural myth.

The Puritan narratives republished and, more importantly, imitated during the Revolutionary era–were equally important, however, in defining the American character by proclaiming the rejection of British culture. Far from a regression in the evolution of the genre, the resurgent interest in the Puritan narratives represents a crucial development in the emergence of a national culture. During the Revolutionary era, the colonists began to see themselves as captives of a tyrant rather than as subjects of a king.

Repurposing Captivity Narratives for Abolition: The transformation in the significance of Rowlandson’s text shows how the captivity narrative could be repurposed to new ends. During the eighteenth century, another repurposing of the captivity narrative was by North American slaves. Briton Hammon’s Narrative (1760) was the first publication by an African American slave. It’s highly significant that the first publication of this sort was a captivity narrative. Hammon follows Rowlandson (and de Vaca before her) in shaping his experience according to the capture – suffering – deliverance formula, and, like Rowlandson, he’s captured by natives. Adapting the captivity narrative to the slave experience offers problems for a modern reader. Yolanda Pierce poses the following dilemma:

The captivity narrative was a white colonial genre before being picked up by black slaves–and the earliest narratives by black slaves, such as Hammon’s, were written by white amanuenses. These contextual nuances point to the many layers that inform an already complicated genre.

- From Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860, University of Oklahoma Press, 1973, p. 94 ↵

- Also titled A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson and A True History of the Captivity & Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson. ↵

- "Redeeming bondage: the captivity narrative and the spiritual autobiography in the African American slave narrative tradition," from The Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative, Cambridge, CUP, 2007, pp. 85-86. ↵