72 Introduction to the Puritan Imagination

Joel Gladd

The video below offers a rough historical overview of the Puritan settlements. It’s important to place them in comparison with early Spanish, French, and English settlements. Here are some important points:

- The first successful English colony, Jamestown, was founded for primarily economic reasons.

- The first shipment of African slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619.

- Virginia, driven by tobacco plantations, became highly stratified, with wealthy aristocrats at the top and slaves on the bottom.

- In Virginia, men vastly outnumbered women.

- The rate of increase (reproduction rate) in Virginia was relatively low, and the mortality rate was high.

- Massachusetts Bay (later called New England) was settled by Pilgrims and Puritans.

- Puritans were Congregationalists who believed congregations should determine their leaders rather than bishops.

- Pilgrims wanted to separate completely from the Church of England.

- In 1620, the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth, during a harsh winter. Squanto helped them survive.

- Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded in 1629. Unlike other colonies, the board of directors also immigrated to the New World.

- Social unity was more important in Massachusetts than in Virginia.

- John Winthrop’s famous “Model of Christian Charity” (1629/30) proposed that the Massachusetts Bay Colony should serve as a model for the rest of the world, as an ideal Christian community, a “city on a hill.”

- Puritan society emphasized literacy and expected everyone to read the Bible.

- Despite having a more egalitarian political structure than communities in the southern colonies, it was much less tolerant towards beliefs that did not align with the official dogma.

The Puritan Model of Increase

As the video above mentions towards the end, one thing that makes the Massachusett’s Bay Colony unique is that its board members immigrated to the New World, rather than remaining in Europe.

What the video doesn’t get into is how the structure of the colonial plantation also contributed to its uniqueness. Early colonial plantations, especially those belonging to the Spanish and French empires, treated New World plantations as extensions of Old World empires. A Spanish conquistador would be granted certain territories under a charter, which allowed them to travel to, e.g., the area that’s now Central America and claim both the territory and inhabitants as part of the colony. Initially the Spanish conquistadors decimated indigenous populations; but later plantations mostly annexed them into the Spanish empire instead of wiping them out. A conquistador would show up, claim the territory and its people, and then Spain would consider that plantation and its mixture of Spanish and indigenous population as an extension of its empire. Spain viewed the existing indigenous population as now part of itself. The empire could be extended by simply declaring existing peoples as under its domain.

The Puritan plantation model was different in some very crucial ways. Rather than annexing entire territories along with the indigenous populations, the Massachusetts Bay Colony never intended to embrace the indigenous population as part of the British empire. Missionaries did attempt to convert the natives (especially the missionary John Cotton), but, from the outset, the Puritans intended to plant itself in a certain area and then grow based entirely on its own rate of increase–by sheer reproduction. We might term this an “internal model of increase.”

This Puritan model of (internal) increase reduced the incentive to conquer indigenous tribes. On the other hand, it also increased the motivation to “purify” an area of people not belonging to the colony. We might view this Puritan model of increase as somewhat anxious towards outsiders, because they thought growth should be entirely from within. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, it remained wary of both annexation and immigration.

Puritan Typology

This lesson will provide some background on the importance of “typological thinking” in the Puritan imagination. When Puritan historians (who were called “chroniclers”) wrote about the history of settling New England, they made their experience meaningful by drawing analogies with Judeo-Christian sacred texts, especially the Old and New Testament.

American literary scholars refer to these interpretative techniques as “Puritan typology,” a phrase that’s crucial for understanding the Puritan imagination.

In Christian thought, typology is the interpretation of Old Testament events, persons, and ceremonies as signs which prefigured Christ’s fulfillment and new covenant with the apostolic church. The concepts arose from those of the skia (shadow) and typos (type). Typology involves identification both of:

- a type or figura, a figure, concept, ceremony, or event as an Old Testament precursor, and

- an anti-type, a New Testament historical figure or event that follows and fulfills the promise of the type.

The fancy term of this is “typological hermeneutics,” which means an interpretative strategy for reading the Judeo-Christian sacred texts that leans heavily on typology. It began in the early medieval period and was–and is–adopted by most Christian communities. For example, Jonah’s three days in the whale (type from the Old Testament) was read as the precursor to Christ’s three days in the tomb (anti-type from the New Testament), and Job’s patience prefigures, or is a figura, of Christ’s forbearance on the cross.

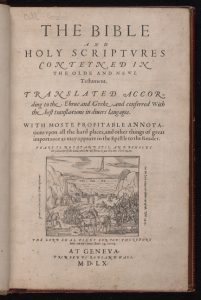

During the medieval period many Saints, theologians, and laypersons extended typology to shed light on current events. It became a way to interpret what was happening in real time, rather than simply in the Judeo-Christian Bible. This practice continued through the early modern period and is highly visible on the frontispiece to the 1560 Geneva Bible (Fig. 1)–the same Bible used by Pilgrims and Puritans.

The Geneva frontispiece depicts the Israelites being chased by Pharoah’s army as they attempt to cross the Red Sea, but the army is dressed in early modern military regalia, complete with chain mail and spears. The Geneva image connects the sixteenth-century persecutions (such as John Knox) with the biblical story. Images such as this suggest any event can potentially become an anti-type to a biblical type.

This biblical interpretive strategy was then applied by Puritans to ongoing events in their “city on a hill” experiment. Puritans repurposed the Exodus story to serve as the type to their own journey across the Atlantic. New England became the anti-type to the promise land of Canaan, as well as New Zion.

This typological approach to history was applied at both the group and individual level. Individual Puritans could make sense of their own spiritual struggles and achievements by identifying themselves with biblical personages like Adam, Noah, or Job. But this broad understanding of typology was not restricted to individual typing; the Puritans also interpreted their group identity as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy, identifying their community as the “New Israel.”

When shifting from the group to the individual level, Puritans were sometimes less confident in whether they were truly a contemporary anti-type to a biblical type. Puritan diaries show that ministers and lay-persons alike agonized over their faith and status. Later in the 17th-century, when Mary Rowlandson wrote about her capture by a native tribe during King Philip’s War, she frequently attempts typology, but her account is a powerful example of its sometimes tentative nature.

Typology is also useful for better understanding how Puritans justified the conquest of native lands and peoples. The logic went like this: since New England was the anti-type to the Old Testament Canaan, the native peoples could be seen as anti-types to the Amalekites or Canaanites. Exodus, Leviticus, and other Old Testament books are full of military exploits that tell a larger story about Israel attempting to settle into its promised land. The Puritans used this model as a framework for thinking about their own conquest–and this typological framework became more entrenched around the King Philip’s War. By the end of the seventeenth-century, Puritans were even more likely to view native peoples as agents of Satan.