74 Phillis Wheatley, Thomas Jefferson, and the debate over poetic genius

Joel Gladd

The following video provides an excellent visual introduction to Phillis Wheatley’s life and art.

Here are some important points from the video:

- She was brought to the colonies after the Great Awakening, which emphasized conversion and personal belief.

- George Whitefield influenced Wheatley and other black Christian authors.

- Wheatley’s first break was in 1770 when she published a poem on George Whitefield.

- Her poetry became a symbol for the anti-slavery movement. It supported arguments for their political equality.

- She gained her freedom in 1773.

- She died prematurely at the age of 31, in 1784.

Phillis Wheatley and Benjamin Franklin

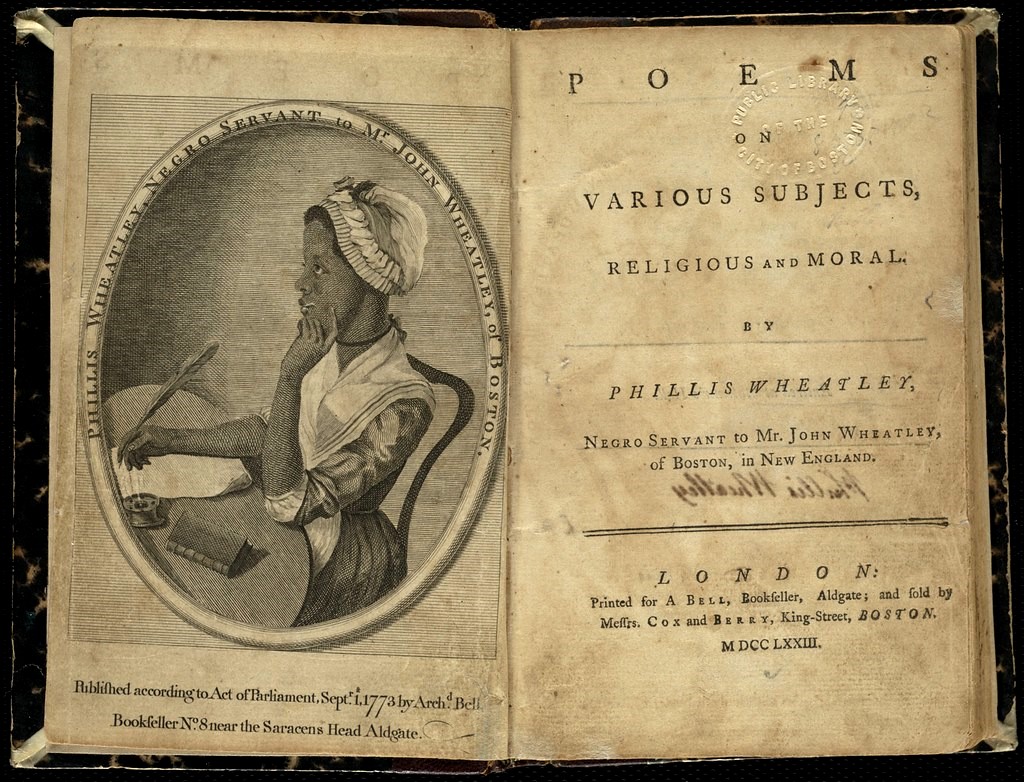

In 1771, Benjamin Franklin sent off a letter to his son William. That letter would eventually become Part 1 of his Autobiography, the first attempt at a modern autobiography in the Americas. Just two years later, in 1773, the first book of poetry by an African American was beginning to circulate, titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, authored by Phillis Wheatley (Fig. 1).

Wheatley remains fascinating in part because she was well-acquainted with so many key historical figures of her time. She was clearly an outsider, but her poetic ambitions also gave access to the most powerful circles in late 18th-century Anglo-American culture.

Wheatley would cross paths with Franklin in the same year after she decamped to London with her master Nathaniel Wheatley. On 7 July 1773, Franklin described this brief meeting:

Upon your Recommendation I went to see the black Poetess and offer’d her any Services I could do her. Before I left the House, I understood her Master was there and had sent her to me but did not come into the Room himself, and I thought was not pleased with the Visit. I should perhaps have enquired first for him, but I had heard nothing of him. And I have heard nothing since of her.

Franklin’s account was rather nonchalant. For other Americans, however, the very fact of Wheatley’s book of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, raised the issue of whether slaves were in fact on par with the white masters.

The most famous debate over Wheatley’s significance was proposed by the author of the Declaration of Independence.

Phillis Wheatley and Thomas Jefferson

In “Query 14” of Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Thomas Jefferson famously critiques Phillis Wheatley’s poetry. In this section of the Notes he addresses views of race and relates his theory of race to both the aesthetic potential of slaves as well as their political futures. He argues that the “sable race” lacks the intellect of the white race. The key differentiator for Jefferson is the ability to “reason” in a pure manner, such that the individual can create something in an original manner. The more original the work of art, Jefferson suggests, the more intellect is displayed. To be fully human, and to be fully capable of reason, means to create original works of art. The highest display of this creative capacity is poetry.

He uses this framework to then treat Wheatley’s poetry. In his view, Wheatley’s poetry is entirely derivative and imitative, completely devoid of originality. This is the highest an African can do, argues Jefferson, and it has nothing to do with the institution of slavery (he points to Roman slaves, such as Epictetus, to suggest white slaves are superior).

Jefferson’s “Query 14” drew the battle lines for future supporters and critics of Wheatley. It should be noted that, from the very beginning, there was no consensus that he was right. In fact many anti-slavery readers responded to Query 14 in order to attack Jefferson’s critique. Rather than being imitative, they argued that Wheatley’s poetry showed true originality and a command of poesy. Wheatley should be seen as a genuine creative genius, they argued. This interpretation was critical to the future of African slaves, because pro-slavery arguments hinged on whether Wheatley and her “race” were capable of true poetry and thus authentic humanity.

In his famous 2002 talk on Wheatley’s legacy, Henry Louis Gates suggests that African American literature is an odd phenomenon because it’s the only global form of literature that exists as a form of political protest. Emerging as it did through this engagement with the Founding Fathers, Black writers in America published their work as evidence of their humanity–as a form of protest against their de- humanization. The pinnacle of this protest was the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, whose unique creative output demonstrated, without refutation, the incredible skill and originality of Black American culture.

Beginning in the late 19th-century, however, Jefferson’s assessment of Wheatley in “Query 14” again reared its head, this time through the mouth of Black Americans who slammed her for being imitative, a disgrace to her race, and having a “white mind,” like Uncle Tom’s mother. Gates calls this the “ideology of authenticity” that reinforces the beliefs of an earlier (Jeffersonian) racist ideology.

The better interpretation of Wheatley, Gates counters, is to recognize the extent to which she step into and developed her own version of classical culture. Culture “can’t be owned,” Wheatley’s poetry suggests.

Gates closes his talk by referring to Frederick Douglass’s support of Thomas Jefferson in 1863, at the height of the Civil War. While Southern slave owners quoted Jefferson’s ideas about race in order to support their pro-slavery positions, Douglass argued that they ignored the much more dominant theme of equality and democracy in his work, demonstrated most clearly by the Declaration of Independence, published in 1776, just a few years after Wheatley attempted her own version of independence.

Gates’s claim that “no one owns culture” is not uncontroversial. Some critics might point out that the classicism of Wheatley’s poetry is based on European civilization, the same people who enslaved Africans and created an ideology of race in order to justify the institution of racism. To ignore the roots of a culture is naive, they suggest.

This debate over Wheatley’s classicism remains pressing. In adopting classical poetics, is Wheatley merely assimilating to white colonial culture, or is something more complex going on?

Binary oppositions in Wheatley’s poetry

Binary oppositions are words and concepts that a community of people generally regards as being opposed to each other. Oppositional thinking represents a black and white view of the world, a tendency to see everything in terms of simple contradictions. These distinctions have consequences for the way power is distributed among groups of people in a society.

For example, in Western society, traditionally the phrase “black and white” has not been a purely descriptive way to view contrasts in the real world. This opposition has been tied to divisive ideas about race, and these ideas about race are linked to other beliefs as well. It’s all packaged together.

Consider how Phillis Wheatley employs the black vs. white dichotomy in her poem, “On Being Brought From Africa to America,” published in 1773:

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

When reading this poem critically, the following oppositions appear (The words in quotes appear in the poem; the words without quotes are the implied opposites.):

“pagan” vs. Christian

lost vs. “redeemed“/”refin’d“

“sable race” vs. European race

“black” vs. white

earthly vs. “angelic“

In writing for a largely white European public, Wheatley reproduces the traditional Christian worldview her readers would recognize. She deftly reads her personal experience–as a captured African in colonial America–through a Christian lens.

For this to work, however, she consistently aligns her pre-captured African identity with the left-hand column (pagan, lost, etc.) and her post-captured colonial identity with the right-hand column (Christian, redeemed, “refin’d”).

The right-hand column above would be considered the “privileged” set of terms. This is typical of how binary oppositions work in a text. Binary oppositions are typically hierarchical, with one half dominating the other. The second term often comes to represent merely the absence of the first. This has the effect of devaluing the second element.

Thus, in traditional Christian thought, “pagan” is a term that refers to a people who don’t yet believe in the “Christian” God. The term “Christian” implies pagan and vice versa, but the former (Christian) is the more desirable identity in early American texts. [The pagan vs. Christian binary, by the way, is not unique to Christianity; it’s analogous to the ancient dichotomy between “barbarian” and Greek citizens, except it’s layered over the theology of the Kingdom of God, good vs. evil, etc. It’s a moralized binary.]

One way to develop your abilities as a critical reader and writer is to not only identify binary oppositions, but also to look for how a primary text (such as Wheatley’s poem above) sets those oppositions in motion. Language is inherently unstable, and it’s impossible for any culture to sustain a perfectly coherent worldview all the time. There are always cracks in culture. It’s constantly in flux.

In individual texts, we can find fissures and gaps where some of the oppositional terms are deployed in unexpected ways, such that the hierarchy of meaning becomes unstable. What we might term “literary” texts tend to play with oppositions more freely. This play can be pushed to the extreme, as in 20th-century postmodern fiction. But a keen reader will be able to spot where any text plays at least a little.

Let’s look again at the final two lines from Wheatley’s poem.

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

The poem’s final couplet seems to argue that the common belief held by many of her European contemporaries (that the “sable race” is less favored the white European race) is nullified by the logic of their own Christian logic of salvation. All must be “refin’d.” It can be argued that this “refining” process would make the logic of binary oppositions that operate throughout the poem mute. This universalizing process is what Frederick Douglass argued for in his reading of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

The reference to Cain is also a pun. Its primary reference is to the biblical story of Cain and Abel, but when read in tandem with the word “refin’d” in the final line, it carries the additional connotation of the eighteenth-century sugarcane refining process, a common reason why the Americas imported so many slaves to the West Indies. This hints rather strongly at the slave labor undergirding much of the colonial economy.

Wheatley’s poetry is often subtle like this. On the surface it’s full of traditional binaries and supports the dominant religion in the colonies. Underneath, and sometimes on the surface, it critiques colonial culture and its slave economy.