68 Hózhó and Navajo Artifacts

Joel Gladd

When considering the complex symbolism and implied narrative of a Mohegan Painted Basket, Stephanie Fitzgerald poses the following question: “What would a history of Native print culture look like if it included three-dimensional texts such as baskets or tipis? How does the inclusion of forms previously not considered texts change conceptions of literacy and communicative practices? How do we begin to read a basket’s narrative?”[1]

Fitzgerald’s questions related to Mohegan Painted Baskets can be applied to many other indigenous artifacts: should we consider these other media as “texts”; and, if so, how do we begin “reading” them? Can a basket be read like a novel or another form of traditional literature? Students taking a literature course often assume that studying literature means reading poems, short stories, and novels. But the issue of indigenous artifacts disrupts these traditional assumptions.

This chapter offers a strategy for interpreting indigenous artifacts–and even rituals–from the Diné (Navajo) culture: by viewing them through the lens of hózhó. Once the key concept of hózhó is understood, it’s possible to begin deciphering the form and purpose of certain artifacts.

Hózhó as a Cultural Lens

When deciphering an indigenous text, it’s often useful to begin with a basic understanding on how it functions within the culture. Many Diné (Navajo) artifacts become much more meaningful to non-native students when a key organizing concept is understood: hózhó. It’s hard to overestimate the significance of hózhó for the Diné.

According to Michelle Kahn-John and Mary Kolthan’s “Living in Health, Harmony, and Beauty: The Diné (Navajo) Hózhó Wellness Philosophy,” hózhó is not just an important word in culture; it’s an entire “complex wellness philosophy” that includes the basic principles of living.

In some accounts, hózhó was given to the Navajo by the female deity Yoołgaii Asdzáá, or White Shell Woman. In Navajo mythology, Yoołgaii Asdzáá becomes Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé, or Changing Woman, a key deity in their religion who was responsible for establishing the first Navajo clans.[2] The deity responsible for establishing the clans also provided them with a guide for living.

When translated into English, hózhó expresses concepts such as “beauty, perfection, harmony, goodness, normality, success, wellbeing, blessedness, order, and ideal.” It’s the “journey by which an individual strives toward and attains this state of wellness.”[3]

Kahn-John and Koithan emphasize the ethical component of hózhó, but it’s important to keep in mind that the term has an aesthetic component to it as well. “Beauty” and “harmony” refer to how one lives in relation to the environment, but these forms of hózhó also apply to the crafts and products that the Navajo make.

This emphasis on the concrete and nearly artisanal nature of hózhó is developed in Donna Haraway’s 2016 book on ecological thinking, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. In her chapter on “Sympoiesis: Symbiogenesis and the Lively Arts of Staying with the Trouble,” Haraway examines Navajo weaving as a form of art activism. She quotes a refrain from the song that Navajo weavers sing when weaving: “‘With me there is beauty (shil hózhó); ‘in me there is beauty’ (shii’ hózhó); ‘from me beauty radiates’ (shits’ aa d oo hózhó).”[4] Haraway considers Navajo weaving a form of activism precisely because hózhó is not just about craft; it’s about “right relations of the world, including human and nonhuman beings, who are of the world as its storied and dynamic substance, not in the world as a container.”[5]

After examining the role of hózhó in their crafts, Haraway shows how this important concept explains the structure of many Navajo legends. The two key mythological figures that relate to hózhó are the Coyote (disorder/chaos) and Spider Woman (order/harmony). In Navajo and other Native American cultures, the Coyote is a trickster figure who is an agent of chaos and disorder. In the Diné Bahane, the Navajo Emergence Story, the night sky begins to take shape through the careful choices of First Man and First Woman (hózhó), but this process is disrupted by the wily Coyote, who snaps a blanket that randomly scatters stars across the sky. The present-day configuration of the sky is a blend of carefully constructed (beautifully-ordered) constellations and chance-driven star clusters.

In order to maintain hózho, present-day Diné must learn to orient themselves according to the carefully ordered constellations. For example, Náhookos Bika’ii (Big Dipper) and Náhookos Bi’áad (Cassiopeia), represent the Male and Female figure and revolve counter-clockwise around Náhookos Biko’ (Polaris), or Central Fire. Thus, the two constellations and Polaris represent the ideal family arrangement: Polaris stands for the fire at the center of the hogan, surrounded by the mother and father. This arrangement suggests what hózhó looks like at the level of the family.

At the personal level, integration happens when individuals learn to maintain hózhó. Paul F. Moulton explains: “If a person does not possess hózhó, he or she is in discord with his or her physical and supernatural surroundings and is in a state of illness.”[6] Thus, various artifacts have been developed by the Diné to help restore balance to those who have fallen out of it, including divination and ceremonial blessings.

Individuals can seek out interventions after having fallen away from balance. More often, however, the Diné life is full of ceremonies and rituals that ceaselessly cultivate hózhó–daily, seasonally, and across generations. These ceremonies and rituals embed hózhó within the Diné life, often by means of material artifacts. The artifacts function as mechanisms for renewing hózhó.

Navajo Ts’aa (Basket) and Hózhó

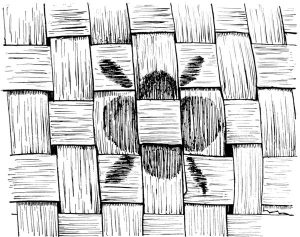

Perhaps the most common example of hózhó in Navajo culture is the traditional Ts’aa, the Diné basket, used in various ceremonies. These baskets are traditionally woven from sumac and include three colors: white, black, and red. In ceremonial wedding baskets, the center includes four or six points, representing the sacred mountains of the Diné. The video below offers an introduction.

While the video above focuses on the wedding basket, similar designs are used for other rites of passage in Navajo culture. They’re critical to key transitional moments because, as Dmitriy Zoxjkie Zeezzhoni suggests, “The ceremonial basket is [a] necessary item for use in Diné ceremonies that are intended to restore balance to a person’s life. … Baskets are used in ceremonies to wash away that ‘bad’, in order to restore harmony and beauty to a person’s life. The Diné traditional basket is the alter to hózhó, it is the universe and it is the Diné world.”

Zeezhoni deciphers the key elements of a traditional basket:

fourth world or “Glittering World.”

2. The white portion of the basket represents dawn and water.

3. The black design in the center symbolizes the sacred mountains of the Diné people. The typical basket contains four or six of these designs. If four appear, they represent the sacred mountains of the east, south, west and north. If the basket has six designs, Huerfano Mountain represents the

doorway and Gobernador Knob the opening of sunlight. There are sacred songs and prayers for these sacred mountains. The prayers protect the Diné from harm, enabling them to give thanks, and direct them in the right direction or path of life.

4. The opening represents the doorway to the thinking and the thoughts of the Diné. It represents the east; Diné prayers and songs are always directed

toward the east.

5. The red bands represent sunshine that help Diné people lead balanced lives that flourish in health and stability, as well as mentally, physically, socially, emotionally, commonly and spiritually. This is also known as hózhó (beauty) in life.

6. The outer black designs represent darkness, black clouds for rain, and snow for folding darkness, which Diné people use to rest their bodies and

minds so that they may continue to grow and develop.

7. The lacing around the edge of the basket represents Diné roots, tying the people to all that are natural in life. It symbolizes the holy circle in which

the Diné sit to say prayers.

8. The weave of the basket represents the complexity and apparentness of life arranged. It is crafted in a careful manner to depict well-being. The

weaving is also never perfect because life is not perfect.

9. The coil starts at the center, representing birth. The mid-red coils symbolize adulthood; the outer black-and-white coils symbolize old age. The coil ends back at the east, or the doorway—life is a continuing cycle

Navajo String Games and Hózhó

A provocative connection that Haraway makes in Staying with the Trouble is between Navajo weaving and their string games, or na’atlo’o’.[7] String games have a cosmic dimension to them–they restore hózhó, by navigating the order found in chaos.

In this video, “Navajo String Games by Grandma Margaret,” we can find a Navajo grandmother reenacting the Coyote scattering the stars across the sky, as well as some of the important constellations.

Creating a “Vortex of Energy” with Hózhó Prayers

The video below offers an introduction to the tradition of praying for hózhó throughout the day, as a way to generate a kind of “vortex of energy”.

Hózhó and Navajo Running

Running plays an important role in Navajo culture, both for men and women. The article “Running Through the Heart of Navajo” explains:

Running is woven into Navajo culture. Their running tradition goes back more than 1,000 years, to the time when they wended their way south from the Northwest Territories to the high desert and buttes of the Four Corners. When a girl undergoes a puberty ceremony, the kinaalda, she sleeps on the dirt floor of a traditional Hogan, which represents a mother’s womb. When the rays of the sun strike the east-facing door, the girl must take a long run.

In Navajo tradition, runners awake in the morning and run toward the sunrise in the East. Similar to the hózhó prayer mentioned above, Navajo runners treat the ritual as a way to maintain hózhó–invoking the sun and running through the sacred territories of their peoples returns order to their lives and nature. A promotional ad produced by Hoka, titled “Time to Hózhó,” offers a glimpse of what this looks like for some.

References

daybreakwarrior. “Navajo String Games by Grandma Margaret.” YouTube, 27 Nov 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qdcG7Ztn3c&feature=youtu.be.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Kahn-John, Michelle and Mary Kolthan. “Living in Health, Harmony, and Beauty: The Diné (Navajo) Hózhó Wellness Philosophy.” Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 2015 May, 4(3): 24-30, 10.7453/gahmj.2015.044.

“Navajo Culture > Role of Women.” PBS, 2017, https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/missnavajo/women.html.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- "The Cultural Work of a Mohegan Painted Basket," from Early Native Literacies in New England, ed. Kristina Bross and Hillary E. Wyss, p. 52. ↵

- https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/missnavajo/women.html ↵

- Kahn-John and Koithan ↵

- 89-90 ↵

- 90. ↵

- "Restoring Identity and Bringing Balance through Navajo Healing Rituals," Music and Arts in Action (Vol 3, Issue 2), p. 81. ↵

- 14 ↵

- daybreakwarrior, "Navajo String Games by Grandma Margaret," https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qdcG7Ztn3c&feature=youtu.be ↵