85 Emily Dickinson’s Private Sublime

Joel Gladd

The following video offers a helpful introduction to reading Emily Dickinson.

Here are some key points from the video:

- She’s considered the poet of paradox

- Dickinson imagines “seeing” as a form of power, playing with the homonym “I” and “eye”

- Many of her poems sound like hymns

- Born in 1830

- Haunted by death

- 1858-1865: wrote 800 poems, but rarely left her room

- Considered an eccentric in Amherst, known for only wearing white outside the home

- For Dickinson, white was the color of passion and intensity; the soul burned white hot

- Poem #465: “I heard a fly buzz”; poem ends with a dash; lines are very iambic, alternating between tetrameter (four feet) and trimeter (three feet); plays with slant rhyme, but ends with strong rhyme that helps with closure

- Dashes = Stronger than a comma, weaker than a period; perhaps expresses the movement of thought

Dickinson’s emblems

One way to think about Dickinson’s poetry is in relation to other mid 19th-century American lyricists, especially those belonging to the Transcendentalist movement. As a contemporary, Walt Whitman often represents the counterpart to Dickinson. Whereas Whitman’s poetry flows forth in an almost libidinal outpouring, overcoming limitations through a spiritual and erotic embrace of all things, Dickinson’s poetry almost seems to contract the world into a deeply private subject/speaker.

Like Eyes that looked on Wastes—

Incredulous of Ought

But Blank–and steady Wilderness—

Just Infinites of Nought—

As far as it could see—

So looked the face I looked upon—

She looked itself–on Me—

The poem above, #458, is typical of Dickinson’s landscape. Rather than cataloguing an epic list of variegated sites, a la Whitman, Dickinson lyrical poetry often interweaves intense emotion, abstract concepts, and just a smattering of concretion curated for effect. Any concrete sensation is, for a Dickinson lyric, highly emblematic of an internal state.

The importance of emblematic framing harkens back to Emerson’s Nature, the foundation of American Transcendentalism. But how to “emblematize” or decode the emblems of nature is precisely what poets such as Whitman and Dickinson work out in distinctive ways. The emblems of Dickinson are inspired by Emerson, but how they operate and what kinds of techniques make them work is very different from Whitman’s hieroglyphics.

Negative emotion into poetry

More recently, Dickinson has attracted attention from disability studies because she had a serious eye problem. It’s assumed she suffered from exotropia; or if not that, she clearly had a condition that impacted her vision. She often complains about trouble with her sight and often uses it as a way to meditate on the relationship between subjectivity and reality, e.g., in poem #258, a “certain Slant of light” “oppresses” her. In other words, there’s a real, literal materiality to some of these meditations. They aren’t just “reflections” on life.

As with her sight disability, Dickinson tends to use disadvantages, limitations, and negative emotions more generally as occasions for glimpsing into something more fundamental about life.

Her poetry reveals a strong connection between biographical fact and its metaphorical equivalent, which is one reason why her poetry was taken up by feminists in the later 20th-century. If Whitman’s sublimity is epic, crossing boundaries to join the immensity of all that is America, Dickinson’s is private and tends to revolve around negative emotions, transforming them into tools of creativity. But she uses this negative emotions to figure creative solutions, alternate assemblages and alliances, as in poem #579:

I had been hungry all the years;

My noon had come, to dine;

I, trembling, drew the table near,

And touched the curious wine.

…

I did not know the ample Bread—

‘T was so unlike the Crumb

The Birds and I, had often shared

In Nature’s–Dining Room—

It’s remarkable how opposite Dickinson feels when reading poems like this. Whereas Whitman imagines overcoming boundaries and enjoying all that life has to offer—in sublime grandeur—Dickinson struggles with her appetites and adopts a stoic minimalism. “A little Bread—a crust—a crumb.”

Another strategy for Dickinson’s coping is to accept suffering rather than flee from it. The speaker of “I cried at Pity—not at Pain” tolerates poverty, starvation, insignificance, and early death.

This insignificance causes her to identify with other creatures: the “Mouse / O’erpowered by the Cat!”, “The Drop, the wrestles in the Sea—” and “a Phebe—nothing more–.”. And yet these lowly beings are often promised release and growth. The mouse claims a heavenly mansion, for example.

One of her most famous poems (from her earlier work) exploits the possibilities of insignificance:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! They’d advertise—you know!

How dreary—to be—Sombedy!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell one’s name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

As critics note, the “Nobody” role may allude to Western mythology’s most memorable exploiter of submerged identity: Ulysses proclaiming himself Noman (sometimes translated as “Nobody”) to evade Polyphemus. Ulysses brought down upon himself the Cyclops’ curse, the wrath of Poseidon, the loss of his men, and ten years of exile after boasting once temporarily safe at sea.

Perhaps appropriately, Dickinson saw literature as a largely affective (emotional) affair, similar to Poe. In a correspondence with Higginson she defined poetry along these lines: “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?”

Dickinson’s poetry might be read as a series of images that attempt to affect the reader in particular ways, like jolts of different energy.

Tension in Dickinson’s lyrics: dashes and enjambment

|

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies [enjambment]

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased [enjambment]

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

|

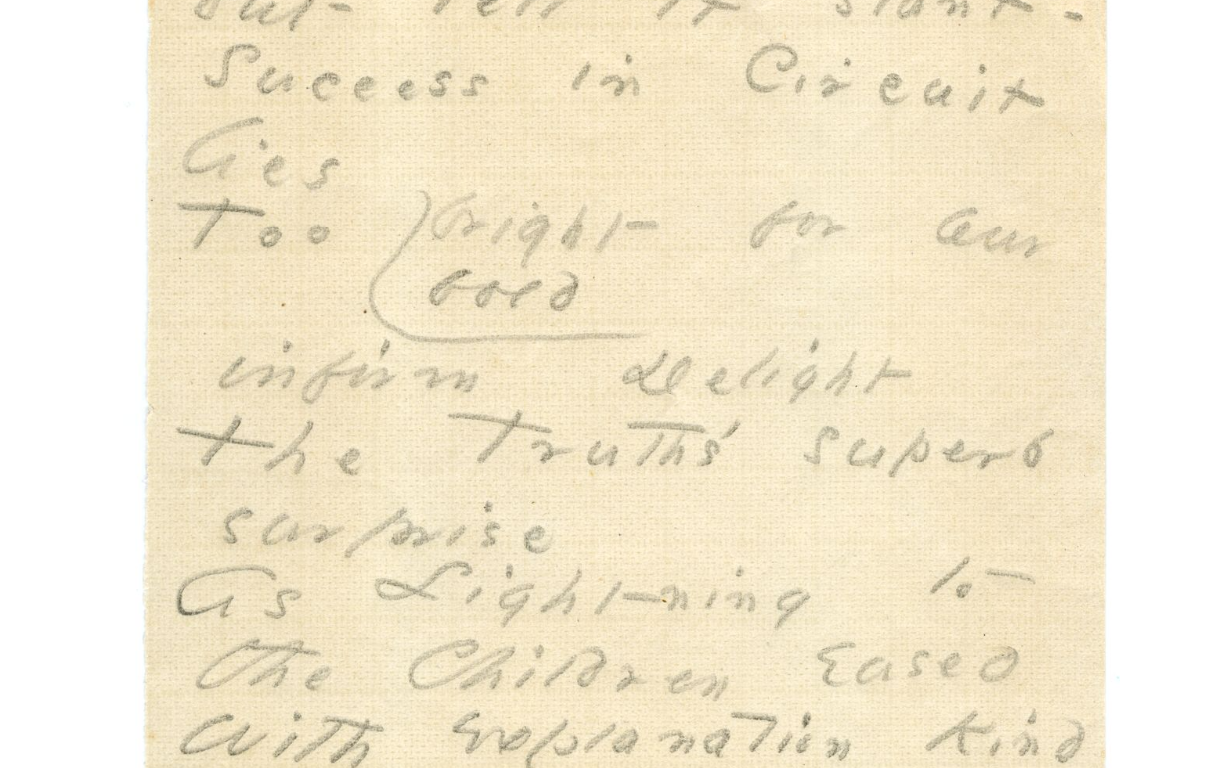

The scan above (Fig. 1) shows Dickinson’s fascicle poem, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” alongside the digitally transcribed modern version. This poem is a typical Dickinson lyric in that it uses two key strategies that tend to make it feel modern: the use of em dashes (lines 1 and 8) and heavy enjambment (especially lines 2 and 5).

Em dashes: Syntactically, the em dash is somewhere between a comma and a period. It feels quicker than a period, but more disruptive than a comma. It can also perform something like the semblance of thought—layering more words and phrases to quickly disrupt or elaborate the previous thought. Dickinson sprinkles them at the ends of beginning, middle, and even final lines in the poem. The latter strategy is illustrated by Fig. 1, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” Ending the poem with a dash creates a sense of tension, despite the fact that lines 6 and 8 rhyme. Dickinson revels in paradox and tension and her heavy use of dashes is a tool she exploits to its fullest potential.

Enjambment: As the Poetry Foundation quickly summarizes, enjambment is “the running-over of a sentence or phrase from one poetic line to the next, without terminal punctuation; the opposite of end-stopped.” This “running-over” technique pervades Dickinson’s poetry, and lends it an aura of modernity.

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics clarifies:

Enjambment can give the reader mixed messages: the closure of the metrical pattern at line end implies a pause, while the incompletion of the phrase says to go on. These conflicting signals can heighten tension or temporarily suggest one meaning only to adjust that meaning when the phrase is completed. To some degree, enjambment has been associated with freedom and transgression since romanticism; such associations are predicated on a norm of end-stopped verse and sparing use of enjambment, in relation to which the enjambment appears liberating. Enjambment ultimately depends on expectation of a pause at line’s end; if verses are enjambed routinely, readers may perceive the text as something like prose.

For example, Dickinson uses enjambment to create ambiguity in the first four lines of “I never hear that one is dead” (#1325):

I never hear that one is dead

Without the chance of Life

Afresh annihilating me

That mightiest Belief,

Too mighty for the Daily mind

That tilling it’s abyss,

Had Madness, had it once or, Twice

The yawning Consciousness,

Beliefs are Bandaged, like the Tongue

When Terror were it told

In any Tone commensurate

Would strike us instant Dead —

I do not know the man so bold

He dare in lonely Place

That awful stranger — Consciousness

Deliberately face —

If the poem is read line by line, the second line clarifies what it means to be dead: when “one is dead,” (1) they no longer have “the chance of Life” (2). However, when the third line is read, it is clear that “Without the chance of Life” is the subject of “annihilating” (meaning: “The thought of someone dying annihilates me”). Despite the syntactic connection between the second and third lines, the connection between the first and second lines is still present in the reader’s mind due to Dickinson’s use of enjambment.

When the fourth line is taken into consideration, the meaning becomes more unstable. If “Without the chance of Life” is the subject of “annihilating” (meaning: “Life’s chance annihilates me”), then what clause does “That mightiest Belief” refer back to? Dickinson’s enjambment complicates how this should be read.

There seem to be two options: either the fourth line is the subject of “annihilating” (“The mightiest belief annihilates me”) or it could indicate that “me” is the mightiest belief (meaning: “The thought of ‘me’ is the mightiest Belief”). Both interpretations are valid.

Thus, the enjambment that unifies the lines into one thought also displaces the meaning of the stanza.

The bigger lesson from closely reading Dickinson is that modern poetry often expresses a tension between sense and the sentence. Poetry such as Dickinson’s assumes the reader is familiar with basic grammatical conventions (such as when to use a comma or period), and the lyrics work by playing and disrupting those expectations. Her use of enjambment and emdashes help explore that fundamental tension.

Since enjambment plays such a large role in modern poetry, in part inspired by Dickinson’s own experiments, it will be helpful to have a firm grasp of what it involves. This introduction by Oregon State University is a helpful supplement to the materials above.

Here are some important points from the video:

- enjambment happens when a line is missing (expected) punctuation at the line break, leading the reader to the next line more quickly

- enjambed lines create tension and pique the reader’s interest; it also speeds up the pacing

- following enjambment, the poem will elaborate or disrupt the previous lines

- the opposite of enjambment is end-stopped: the end of the line completes a phrase and is often capped with a punctuation mark

- modern poems often interweave enjambed and end-stopped lines