73 Benjamin Franklin, Personal Narratives, and the Art of Self-Cultivation

Joel Gladd

The purpose of this chapter is three-fold. First, it shows how Benjamin Franklin built on the legacy of Puritans such as Cotton Mather. Second, it explains how Franklin’s Autobiography fits within the early modern personal narrative. Third, it shows how Franklin’s emphasis on “industry” and “self-cultivation” participates in a genealogy of Western self-examination.

From Cotton Mather’s religious humanitarianism to Benjamin Franklin’s public service projects

A common binary we accept in modernity is between religious orthodoxy (or religion more generally) and science. However, when a smallpox epidemic broke out in 1721, it was Cotton Mather—the leading religious authority in New England—who led the most sophisticated inoculation campaign in that period. Inoculation was an early form of vaccination that was heavily debated when he proposed it. Mather himself reported that he learned about this early form of vaccination from his West African slave Onesiums, who himself claimed it was used in West Africa. Mather read other reports on vaccination and decided it was an effective solution to yet another smallpox outbreak in Boston.

Students who are mainly familiar with Mather through his Wonders of the Invisible World may be surprised by his interest in science, but he was a man of incredible breadth. Mather was the preeminent scientific thinker in Puritan New England, even while he maintained an “apocalyptic imagination.” He also maintained an interest in what we would now call “public service projects.” His publication, Bonafacius: Essays To Do Good (1710), argued forcibly for an investment in one’s local community by doing good works. It had everything to do with the Kingdom of God in his view: servicing the public was one way to bring the Kingdom closer. He viewed his vaccination campaign as part of that project.

Mather joined forces with a practicing physician, Dr. Boylston, and when their vaccination campaign started they were vociferously opposed by another group of doctors who claimed they were murderers.

The feud between pro-vaccination and anti-vaccination doctors made its way into a new magazine, the New England Courant, which became the mouthpiece of the anti-vaccination physicians. This magazine was founded and run by someone called James Franklin, who employed his brother, Benjamin Franklin, as an apprentice. Franklin was an aspiring printer and writer who began sneaking articles into the weekly under the pseudonym Silence Dogwood in order to jumpstart his career. Later, when James discovered the ruse, he became furious at his brother’s machinations.

The vaccination feud accelerated in August of 1721:

When the next smallpox epidemic broke out years later, the anti-vaccination doctors decided to take Mather’s smallpox vaccine, eventually vindicating his strategy.

Like today, the inoculation feud was enormously lucrative for the local media, especially the New England Courant. In 1722, however, James Franklin published a commentary on local events that seemed to attack local officials. This attack got him thrown in jail. As a result, the younger Franklin temporarily took his brother’s place running the weekly. His statement only exacerbated tensions with his brother. In 1723, Franklin still had a few years left as an apprentice, but he decamped to Philadelphia to escape his brother’s overbearing influence.

When Franklin returned to Boston a few years later, he visited Cotton Mather, whom he viewed as a sort of scientific mentor. Mather wrote about North American fossils, the hybridization of plants, and of course led New England public health efforts in the area of inoculation. Mather even referred to Isaac Newton as his own mentor in science.

Franklin’s first major publishing effort after his Silence Dogwood series, Poor Richard’s Almanac, can be seen as part of his efforts to extend the legacy of Mather’s emphasis on science and public health. Whereas Mather viewed his efforts theologically, as an effort to further the Kingdom of God, Poor Richard began to translate the general welfare in ways that sound more similar to the Enlightenment era. In 1753, “Poor Richard Improved” phrased this as a Deist: “Serving God is Doing Good to Man, but Praying is thought an easier Service, and therefore more generally chosen.”[2]. Doing good is the entire point, Franklin suggests, not whether those works can be justified theologically.

Franklin’s increasingly dominant influence in Philadelphia, New England, and the colonial publishing industry more generally demonstrates the shift from Mather’s Puritan religious humanitarianism to a way of thinking that advocated more generally for humanitarian institutions. Franklin founded local hospitals, established the first public library in the colonies, and founded the first fire station. In this way, Franklin retained the ethos of Mather’s Bonafacius: Essays To Do Good, but began the process of bracketing what he saw as the unnecessary theological trappings. As Franklin demonstrates throughout the Autobiography, he’s often more interested in the most pragmatic and moral effects of religion rather than disputes over doctrine.

Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and the Early Modern Personal Narrative

As the brief overview above suggests, Franklin was himself a type of escapee—from his early apprenticeship. He even escaped by ship to his eventual homeland. This pattern is eerily similar to other captivity narratives of his time. In fact scholars have suggested it’s possible to read Franklin’s own account of his life, in his Autobiography, as having a conversation with early modern captivity narratives.

In 1760, the first captivity narrative by a black slave was published in North America, titled A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surpizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man. The narrative begins in a way that has strong echoes of Rowlandson’s Puritan Narrative (1682), the most popular captivity narrative of its time:

The bolded text above shows the kind of typological language we expect in Puritan Christian narratives. It’s a story about an (enslaved) protagonist being captured by the natives, who are typed as “so many Devils.” Hammon’s experience throughout the captivity is framed much like Rowlandson’s, as part of a test, a “Mount of Difficulty” governed by God’s Providence. He eventually becomes delivered—except here, he’s delivered to his master, remaining a slave (modern readers should keep in mind it was written by an amanuensis). What’s important to note is how it uses the extremely influential Puritan typology to interpret the black slave experience.

During this period, the distinction between captivity narratives, religious pamphlets, and modern publications such as biographies and autobiographies hadn’t yet been cleanly separated. It was all fused together in a more general category of “personal narrative.”

Personal narrative is a rather large umbrella term. It refers to first-person accounts such as diaries, journals, letters, or autobiographies. However, it also includes sub-genres, such as captivity narratives, which in turn are related to slave narratives. Stepping back, we can consider these proto-autobiographies as belonging to two ancient traditions.

The first classical influence is Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, from the second century. Plutarch tells the story of famous Greek and Roman figures, pairing them strategically to illustrate a moral lesson. For example, he compares Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. His goal was moral instruction and edification.

The other tradition can be traced back to Augustine’s Confessions (397-400 AD). This personal narrative is a conversion narrative and is largely seen as the first Christian “autobiography.” That term (autobiography) is modern, however, and has more specific connotations that wouldn’t emerge until the eighteenth century (see below). The basic structure of his Confessions follows the typology of Jonah and the “lost and found” parables from the Christian Gospels.

One of the most famous eighteenth-century personal narratives was Jonathan Edwards’s Personal Narrative, a conversion narrative that offers a fairly informal account of his spiritual struggles. His conversion narrative was not meant to be comprehensive; it’s certainly not an “autobiography” in the modern sense. Personal narratives such as Edwards’s were tightly focused on spiritual development and meant for the edification of the reader.

It wasn’t until the late eighteenth-century that personal narratives began to take on a more comprehensive scope. Rather than an account of one’s spiritual development (Augustine, Edwards) or escape from the natives (Rowlandson, Hammon), some late eighteenth-century narratives attempted to capture the author’s entire life, from birth to maturity. The comprehensiveness of this genre practiced the Enlightenment ideals of transparency and comprehensiveness. Modern autobiographies emerged in this era. They did not drop the “edification” trappings of Plutarch and Augustine. However, Enlightenment autobiographies became absorbed with attention to detail. Not everything could be tied to a moral lesson, these accounts suggested, and that was perfectly fine. Preserving and accounting for one’s life was, in its own way, a type of virtue.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions first appeared in 1782, four years after the author’s death, and the remainder in 1789. Rousseau claimed that his narrative was “the only portrait that exists and that will probably ever exist of a man, copied exactly from nature and in all its truth”; he offered it as “a standard of comparison for the study of men, which has yet to be undertaken,” thus linking it to the Enlightenment projects of moral and anthropological inquiry. His decision to depict his sexual experiences, his bodily illnesses, and episodes of shameful behavior in his life set a new standard for self-revelation that continues to influence discussions of psychology down to the present.

In colonial America, Benjamin Franklin began a similar experiment in 1771 and completed it in 1790. At first, he called this work his Memoirs. The label of Autobiography was given to the text (or series of texts) retrospectively, once that genre was firmly established. Franklin’s Memoirs are distinctive because (like Rousseau) he presents his life as emblematic of a larger social experiment. While Rousseau saw himself as performing the Enlightenment through radical self-exposure, Franklin presents himself as a model colonial citizen who works tirelessly to better himself and those around him. He represents himself as the new colonial subject (a free citizen) who practically builds his life out of scratch, through hard work (what he calls “industry”). Franklin’s brand of personal narrative is a distinctive departure from Rowlandson, Edwards, and others in how little recourse he makes to biblical typology. On the contrary: in Part 2 of his Autobiography he attempts to one-up official Church teachings by achieving moral perfection on his own terms.

Yet his frequent concerns with work and service reflect what Max Weber famously termed “the Protestant Work ethic.” Just as Mary Rowlandson’s Narrative took on a more secular hue during the Revolutionary era, Franklin’s Autobiography is a testament to the unique blend of colonial Protestantism and secular Enlightenment values.

Modern Liberalism and Franklin’s attempt at moral perfection

Franklin has often been identified with the most prominent “self-made man” in American culture. His autobiography remains an important touchstone for contemporary entrepreneurs, such as Tim Ferriss, who view his famous tome as the prototype for how to successfully achieve the American Dream, or how to “pull oneself up by your own bootstraps,” as the saying goes. The Autobiography has been treated by Max Weber and other modern scholars as the best illustration of how the Calvinist work ethic–from Cotton Mather and other 17th-century Puritans–fused with the industry of eighteenth-century capitalism. Franklin shows what it takes, we’re told, to embrace life as an emerging homo economicus, the citizen as business person, one who is constantly looking for ways to be industrious and make money.

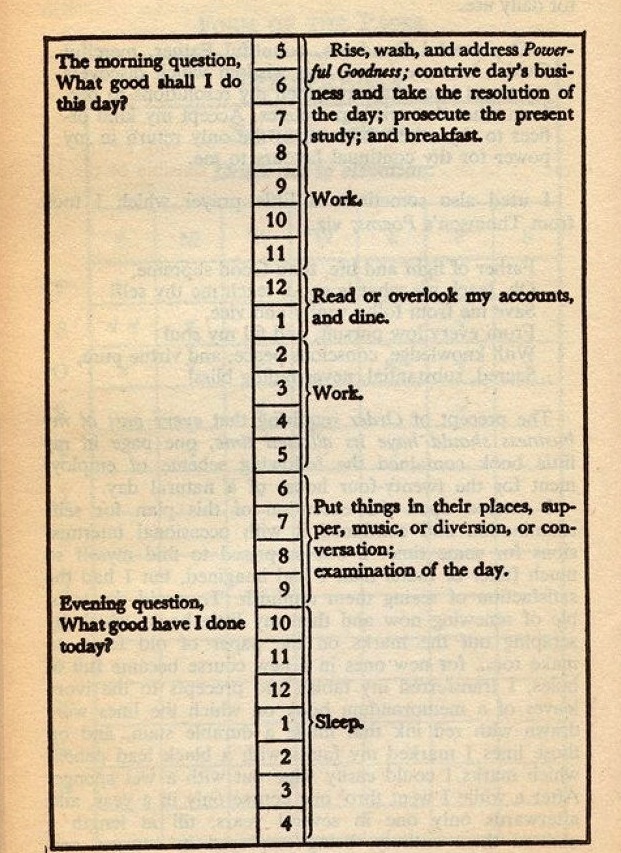

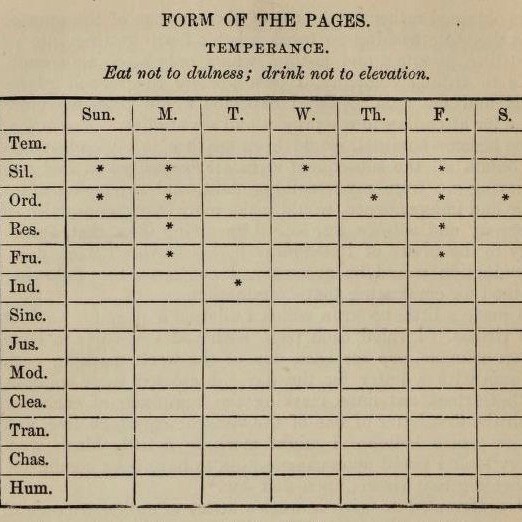

This portrait of Franklin as the preeminent homo economicus is illustrated by his famous attempt, in Part II, to achieve moral perfection. In this section he presents his schedule for the day, along with a detailed account of his attempt to master virtues such as “Temperance.”

|

|

This detailed attempts at moral perfection can be aligned with the “art of self-cultivation” that began to coalesce during the eighteenth century. This shift has been carefully scrutinized by Michel Foucault, whose The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978-79 points to Franklin as a key figure. Increasingly, the Anglo-American form of government began to be articulated as “frugal government,” or “one who governs best is one who governs least.” Foucault considers this an important “epoch” in Western governance.[3]. Foucault’s later lectures, captured by The Hermeneutics of the Subject, focus more intently on the flipside of this emerging form of governance: the self-reliant individual (in some courses or in popular news sources students might see the term “neo-liberalism”–that’s a connected idea). For Foucault and other scholars, the form of frugal government that Franklin advocated (and eventually led to the early colonial framework and U.S. Constitution) expected governance to be taken over by individuals who actively worked on themselves. Instead of authorities disciplining the population in a hierarchical manner, Western governance increasingly looked for ways to foster self-governance, a form of soft power often achieved by non-political institutions such as religion.

Stoic self-examination: Franklin’s autobiography practices this art of self-governance by tapping into an ancient technique: the “self-examination.” The self-examination technique can be traced to something called the “Pythagorean examination of the day,” but it also has parallels in the Socratic dialogues and elsewhere:

- Do only that which will not hurt you, and think carefully about what you are going to do before you do it.

- Never fall asleep after going to bed,

- Till you have carefully considered all your actions of the day:

- Where have I gone amiss? What have I done? What have I omitted that I ought to have done?

- If in this examination you find that you have gone amiss, reprimand yourself severely for it;

- And if you have done any good, rejoice.

- Practice thoroughly all these things; meditate on them well, for you ought to love them with all your heart.

- It is they that will put you on the path of divine virtue.

- I swear it by the one who has transmitted into our souls the Sacred Quaternion, the source of nature, whose cause is eternal.

- But never begin to set your hand to any work, till you have first prayed to the gods to accomplish what you are about to begin. . . . observe justice in your actions and in your words.

- When you have become familiar with this habit,

- You will know the constitution of the Immortal Gods and of humans.[4]

Lines 39-44 above capture the essence of the examination: before going to bed, meditate on the day’s actions, looking for errors and good deeds. If errors are spotted, troubleshoot. This practice was taken up by the Roman stoics. In Seneca’s treatise On Anger, for example, he imitates the habit of Sextius:

Seneca’s self-examination continued the Pythagorean tradition of troubleshooting. The “self” was something to be worked on, and every individual had the means to work on themselves–they did not need to pray to a higher being, for example.

In the medieval period, self-examination was taken up by Christian saints and theologians who now introduced a new idea: the conscience. Instead of focusing on errors and deeds, Christian figures now focused on thoughts and intentions. It wasn’t the deed itself that was problematic. Instead, it was the will or intention behind the deed. And whereas Stoics retreated into a private life to work on themselves, Christianity emphasized the importance of confession. Spiritual literature offered a path for continually analyzing one’s impure thoughts, helping to verbalize them and purify the inner soul of corruption (exomologesis).

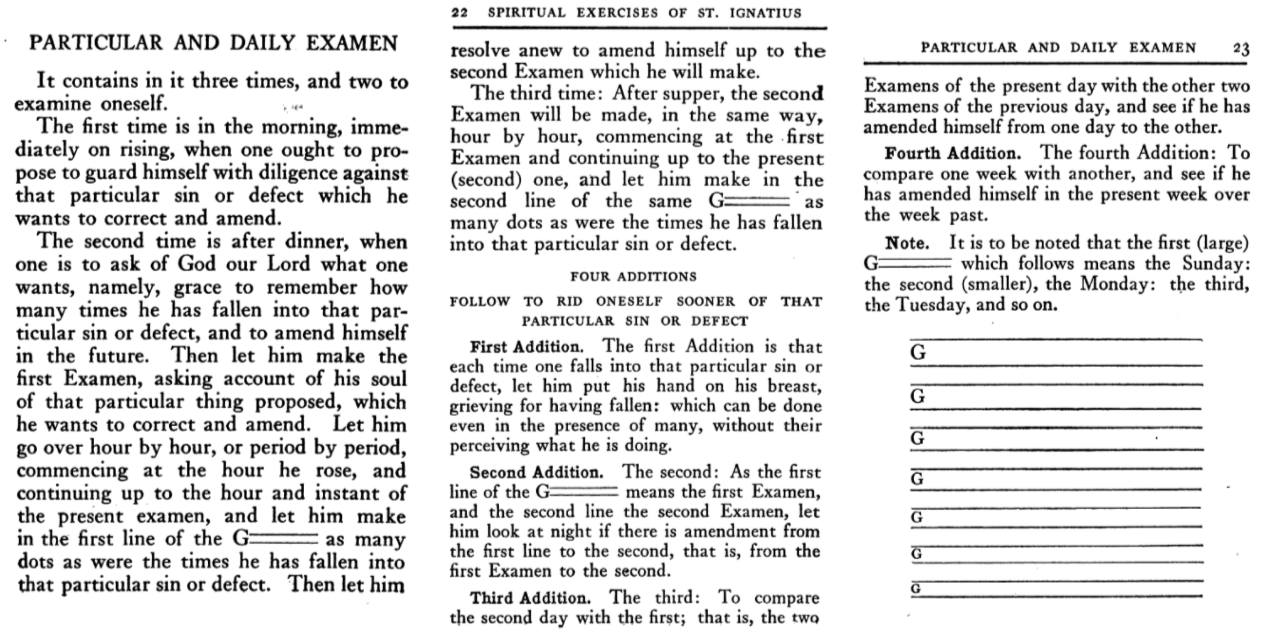

This layering of Christian confession over Stoic self-examination can be seen very clearly in St. Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises (1522-1524):

Notice the basic pattern that follows Seneca’s self-examination. But immediately, with “First Addition,” St. Ignatius offers the Christian framing: “let him put his hand on his breast, grieving for having fallen … .” Seneca, by contrast, explicitly exhorts his reader not to grieve.

This brief genealogy of the self-examination in Western culture demonstrates how the “working on oneself,” or self-governance, became transformed over time by Christianity. When Franklin re-introduces the self-examination in Part II of his Autobiography, he is tapping into an ancient practice–but he’s also selecting parts of that tradition rather than others. Does his daily schedule and attempt at moral perfection seem more similar to Seneca or St. Ignatius?

Key biographical details from Franklin’s Autobiography

If you’re new to Franklin’s Autobiography, it’s a sprawling volume that jumps around in time and in content. The following video is important for getting a basic feel of how it works.

Here are key points from the video not covered by the rest of this chapter:

- It’s written in two parts, the first as a letter to his son, the second part several years later

- Franklin attempted his first public project, a subscription library, in 1730

- Reading was the only amusement Franklin allowed himself, setting aside 1-2 hours a day

- He attempted a project of moral perfection

- At the same time, he remained interested in public projects; in 1743, he started a philosophical society

- He proposed local militias

- In 1746, Franklin began his experiments with electricity

- In 1756, Franklin was sent to protect a territory from natives

- Later, Franklin was sent to England as a delegate to petition the King

- He was part of the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence

- From S.L. Kotar and J.E. Gessler's Smallpox: A History, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC, 2013, p. 37. ↵

- qtd. in Benjamin Franklin in American Thought and Culture: 1790-1990, Waltham, MA, 1994, p. 18 ↵

- See "17 January 1979," ed. Michel Senallart, trans. Graham Burchell, p. 29 ↵

- Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library, Newburyport, MA: Red Wheel Weiser, 1987, p. 163. ↵

- Anger, Mercy, Revenge, trans. Robert A. Master and Martha C. Nussbaum, University of Chicago, 2010, p. 91 ↵