7 Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

Sam Gagnon

Introduction

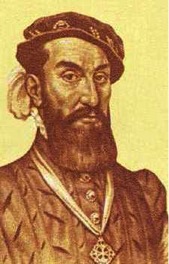

Born anywhere between 1488-1492, Cabeza De vaca was an explorer of Spanish descent. More notably one of the four survivors of the “Narvaez expedition.” While traveling across what is now the southwestern portion of the United States for eight years, he became a trader and healer to various Native American tribes before relocating back to Mexico so that he could join Spanish colonial forces in the area. Returning to his native country in 1537, De Vaca wrote an account that was officially published in 1542 about his Anthropological observations while interacting with indigenous tribes. In 1540, De Vaca was appointed as “adelantado”, which is similar to being a governor, or elected official to oversee a particular region or area. He served as Adelantado of the Rio De La Plata, which fell under a portion of Argentina’s boundaries.

While in Argentina, De Vaca spent a great deal of time increasing the population in Buenos Aires. This is because due to the poorly orchestrated administration at the time, population dwindled. Condequently, De Vaca would be transported to Spain to be put on trial in 1545, though he never received a sentence. He ended up passing away in Seville between 1557-1560.

As an observer of Native American practices and behaviors, De Vaca spent many years with various peoples including the Capoque, Han, Avavare, and Arbadao. Most of which he recorded included details about the inhabitants treatment of offspring, their marriage practices, and their sources of food.

Relating to the texts in class, Cabeza De Vaca departed Spain For the Americas around 1527. In April of 1528, he landed near what is now Tampa Bay with a league of soldiers. Exhausted and distressed by lack of food, De Vaca’s expedition went north, and then west along the southern coast of Florida near the Gulf Of Mexico. While there, De Vaca pressed forth, heading towards Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. In the process, three boats were lost, including a good portion of the men. Cabaza and a few of him men were a few of the remaining survivors after those that did end up surviving the ship wreckage were wiped out by hunger and attacks. They named where they landed “The Island Of Misfortune”, real location somewhere in the proximity of Texas. From 1529 to 1534, De Vaca and his accomplices lived in semi-slavery, where they cooperated with the natives of the region, and as a result, De Vaca improved upon his skills as a medical man. Branching off into east Texas, De Vaca hoped to reach Mexico and find some Spanish settlers along the way. Crossing the Pecos and Colorado River, with the assistance of some Native Americans, De Vaca made in to Mexico and was located by another Spanish party. He returned to Spain in 1537 with notes on his findings.

Works Cited:

- –americanjourneys.org/aj-070/

- Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81lvar_N%C3%BA%C3%B1ez_Cabeza_de_Vaca

Relation of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

Prologue

Sacred Caesarian Catholic Majesty : ‘ Among the many who have held sway, I think no prince can be found whose service has been attended with the ardor and emulation shown for that of your Highness at this time. The inducement is evident and powerful : men do not pursue together the same career without motive, and strangers are observed to strive with those who are equally impelled by religion and loyalty. Although ambition and love of action are common to all, as to the advantages that each may gain, there are great inequalities of fortune, the result not of conduct, but only accident, nor caused by the fault of any one, but coming in the providence of God and solely by His will. Hence to one arises deeds more signal than he thought to achieve ; to another the opposite in every way occurs, so that he can show no higher proof of purpose than his effort, and at times even this is so concealed that it cannot of itself appear. As for me, I can say in undertaking the march I made on the main by the royal authority, I firmly trusted that my conduct and services would be as evident and distinguished as were those of my ancestors, and that I should not have to speak in order to be reckoned among those who for diligence and fidelity in affairs your Majesty honors. Yet, as neither my counsel nor my constancy availed to gain aught for which we set out, agreeably to your interests, for our sins, no one of the many armaments that have gone into those parts has been permitted to find itself in straits great like ours, or come to an end alike forlorn and fatal. To me, one only duty remains, to present a relation of what was seen and heard in the ten years I wandered lost and in privation through many and remote lands.’ Not merely a statement of positions and distances, animals and vegetation, but of the diverse customs of the many and very barbarous people with whom I talked and dwelt, as well as all other matters I could hear of and discern, that in some way I may avail your Highness. My hope of going out from among those nations was always small, still my care and diligence were none the less to keep in particular remembrance everything, that if at any time God our Lord should will to bring me where I now am, it might testify to my exertion in the royal behalf. As the narrative is in my opinion of no trivial value to those who in your name go to subdue those countries and bring them to a know- ledge of the true faith and true Lord, and under the imperial dominion, I have written this with much exactness ; and although in it may be read things very novel and for some persons difficult to believe, nevertheless they may without hesitation credit me as strictly faithful. Better than to exaggerate, I have lessened in all things, and it is sufficient to say the relation is offered to your Majesty for truth. I beg it may be received in the name of homage, since it is the most that one could bring who returned thence naked.

Chapter VII: The Character of the Country (excerpt)

The country where we came on shore to this town and region of Apalachen, is for the most part level, the ground of sand and stiff earth. Throughout are immense trees and open woods, in which are walnut, laurel and another tree called liquid-amber, cedars, savins, evergreen oaks, pines, red-oaks and palmitos like those of Spain. There are many lakes, great and small, over every part of it; some troublesome of fording, on account of depth and the great number of trees lying throughout them. Their beds are sand. The lakes in the country of Apalachen are much larger than those we found before coming there. In this Province are many maize fields ; and the houses are scattered as are those of the Gelves. There are deer of three kinds, rabbits, hares, bears, lions and other wild beasts. Among them we saw an animal with a pocket on its belly, in which it carries its young until they know how to seek food; and if it happen that they should be out feeding and any one come near, the mother will not run until she has gathered them in together. The country is very cold. It has fine pastures for herds. Birds are of various kinds. Geese in great numbers. Ducks, mallards,royal-ducks, fly-catchers, night-herons and partridges abound. We saw many falcons, gerfalcons, sparrow- hawks, merlins, and numerous other fowl.

Two hours after our arrival at Apalachen, the Indians who had fled from there came in peace to us, asking for their women and children, whom we re- leased ; but the detention of a cacique by the Governor produced great excitement, in consequence of which they returned for battle early the next day, and attacked us with such promptness and alacrity that they succeeded in setting tire to the houses in which we were. As we sallied they fled to the lakes near by, because of which and the large maize fields, we could do them no injury, save in the single instance of one Indian, whom we killed. The day following,t others came against us from a town on the opposite side of the lake, and attacked us as the first had done, escaping in the same way, except one who was also slain. We were in the town twenty-five days,J in which time we made three incursions, and found the country very thinly peopled and difficult to travel for the bad passages, the woods and lakes. We inquired of the cacique we kept and the natives we brought with us, who were the neighbors and enemies of these Indians, as to the nature of the country, the character and condition of the inhabitants, of the food and all other matters concerning it. Each answered apart from the rest, that the largest town in all that region was Apalachen; the people beyond were less numerous and poorer, the land little occupied, and the inhabitants much scattered ; that thenceforward were great lakes, dense forests, immense deserts and solitudes. We then asked touching the region towards the south, as to the towns and subsistence in it. They said that in keeping such a direction, journeying nine days, there was a town called Ante, the inhabitants whereof had much maize, beans and pumpkins, and being near the sea, they had fish, and that those people were their friends. In view of the poverty of the land, the unfavorable accounts of the population and of everjrthing else we heard, the Indians making continual war upon us, wounding our people and horses at the places where they went to drink, shooting from the lakes with such safety to themselves that we could not retaliate, killing a lord of Tescuco,^ named Don Pedro, whom the Com- missary brought with him, we determined to leave that place and go in quest of the sea, and the town of Ante of which we were told.

At the termination of the twenty-five days after our arrival we departed,* and on the first day got through those lakes and passages without seeing any one, and on the second day we came to a lake difiicult of cross- ing, the water reaching to the paps, and in it were numerous logs. On reaching the middle of it we were attacked by many Indians from behind trees, who thus covered themselves that we might not get sight of them, and others were on the fallen timbers. They drove their arrows with such eiFect that they wounded many men and horses, and before we got through the lake they took our guide. They now followed, en- deavoring to contest the passage ; but our coming out afforded no relief, nor gave us any better position ; for when we wished to fight them they retired immedi- ately into the lake, whence they continued to wound our men and beasts. The Governor, seeing this, com- manded the cavalry to dismount and charge the In- dians on foot. Accordingly the Comptroller alighting with the rest, attacked them, when they all turned and ran into the lake at hand, and thus the passage was gained.

Some of our men were wounded in this conflict, for whom the good armor they wore did not avail. There were those this day who swore that they had seen two red oaks, each the thickness of the lower part of the leg, pierced through from side to side by arrows ; and this is not so much to be wondered at, considering the power and skill with which the Indians are able to project them. I myself saw an arrow that had entered the butt of an elm to the depth of a span. The Indians we had so far seen in Florida are all archers. They go naked, are large of body, and ap- pear at a distance Uke giants. They are of admirable proportions, very spare and of great activity and strength. The bows they use are as thick as the arm, of eleven or twelve palms in length, which theywill discharge at two hundred paces with so great pre- cision that they miss nothing.

Chapter VIII: We Go from Aute (excerpt)

The next morning we left Aute,* and traveled all day before coming to the place I had visited. The journey was extremely arduous. There were not horses enough to carry the sick, who went on increas- ing in numhers day hy day, and we knew of no cure. It was piteous and painful to witness our perplexity and distress. “We saw on our arrival how small were the means for advancing farther. There was not any where to go ; and if there had been, the people were unable to move forward, the greater part being ill, and those were few who could be on duty. I cease here to relate more of this, because any one may suppose what would occur in a country so remote and malign, so destitute of all resource, whereby either to live in it or go out of it ; but most certain assistance is in Grod, our Lord, on whom we never failed to place reliance. One thing occurred, more afflicting to us than all the rest, which was, that of the persons mounted, the greater part commenced secretly to plot, hoping to secure a better fate for themselves by abandoning the Governor and the sick, who were in a state of weak-ness and prostration. But, as among them were many hidalgos and persons of gentle condition, they would not permit this to go on, without informing the Governor and the officers of your Majesty; and as we showed them the deformity of their purpose, and placed before them the moment when they should desert their captain, and those who were ill and feeble, and above all the disobedience to the orders of your Majesty, they determined to remain, and that whatever might happen to one should be the lot of all, without any forsaking the rest.

After the accomplishment of this, the Governor called them all to him, and of each apart he asked advice as to what he should do to get out of a country so miserable, and seek that assistance elsewhere which could not here be found, a third part of the people being very sick, and the number increasing every hour; for we regarded it as certain that we should all become so, and could pass out of it only through death, which from its coming in such a place was to us all the more terrible. These, with many other embarrassments being considered, and entertain- ing many plans, we coincided in one great project, extremely difficult to put in operation, and that was to build vessels in which we might go away. This ap- peared impossible to every one : we knew not how to construct, nor were there tools, nor iron, nor forge, nor tow, nor resin, nor rigging; finally, no one thing of so many that are necessary, nor any man who had a knowledge of their manufacture; and, above all,there -was nothing to eat, while building, for those who should labor…

Before we embarked there died more than forty men of disease and hunger, without enumerating those destroyed by the Indians. By the twenty-second of the month of September,* the horses had been con- sumed, one only remaining ; and on that day we em- barked in the following order : In the boat of the Governor went forty-nine men ; in another, which he gave to the Comptroller and the Commissary, went as many others ; the third, he gave to Captain Alonzo del Castillo and Andres Dorantes, with forty-eight men; and another he gave to two captains, Tellez and Pena^ losa, with forty-seven men. The last was given to the Assessor and myself, with forty-nine men. After the provisions and clothes had been taken in, not over a span of the gunwales remained above water ; and more than this, the boats were so crowded that we could not move : so much can necessity do, which drove us to hazard our hves in this manner, running into a turbu- lent sea, not a single one who went, having a know- ledge of navigation.

Chapter X: The Assault from the Indians (excerpt)

The morning having come,* many natives arrived in canoes who asked us for the two that had remained in the boat. The Governor replied that he would give up the hostages when they should bring the Christians they had taken. “With the Indians had come five or six chiefs, who appeared to us to be the most comely per- sons, and of more authority and condition than any we had hitherto seen, although not so large as some others of whom we have spoken. They wore the hair loose and very long, and were covered with robes of marten such as we had before taken. Some of the robes were made up after a strange fashion, with wrought ties of lion skin, making a brave show. They entreated us to go with them, and said they would give us the Christ- ians, water, and many other things. They continued to collect about us in canoes, attempting in them to take possession of the mouth of that entrance ; in con- sequence, and because it was hazardous to stay near the land, we went to sea, where they remained by us until about mid-day. As they would not dehver our people, we would not give up theirs ; so they beganto turl clubs at us and to throw stones with slings, making threats of shooting arrows, although we had not seen among them all more than three or four bows. “While thus engaged, the wind beginning to freshen, they left us and went back…

When day came, the boats had lost sight of each other. I found myself in thirty fathoms. Keeping my course until the hour of vespers, I observed two boats, and drawing near I found that the first I ap- proached was that of the G-overnor. He asked me what I thought we should do. I told him we ought to join the boat which went in advance, and by no means to leave her ; and, the three being together, we must keep on our way to where Grod should be pleased to lead. He answered saying that could not be done, because the boat was far to sea and he wished to reach the shore ; that if I wished to follow him, I should order the persons of my boat to take the oars and work, as it was only by strength of arm that the land could be gained. He was advised to this course by a captain with him named Pantoja, who said that if he did not fetch land that day, in six days more they would not reach it, and in that time they must inevit- ably famish. Discovering his will I took my oar, and so did every one his, in my boat, to obey it. We rowed until near sunset ; but the Governor having in his boat the healthiest of all the men, we could not by any means hold with or follow her. Seeing this, Iasked Mm to give me a rope from his boat, that I might be enabled to keep up with him ; but he an- swered me that he would do no little, if they, as they were, should be able to reach the land that night. I said to him, that since he saw the feeble strength we had to follow him, and do what he ordered, he must tell me how he would that I should act. He answered that it was no longer a time in which one should com- mand another] but that each should do what he thought best to save his own life ; that he so intended to act; and saying this, he departed with his boat…

Near the dawn of day, it seemed to me I heard the tumbhng of the sea ; for as the coast was low, it roared loudly. Surprised at this, I called to the master, who answered me that he beheved we were near the land. We sounded and found ourselves in seven fathoms. He advised that we should keep to sea until sunrise ; accordingly I took an oar and pulled on the land side, until we were a league distant, when we gave her stern to the sea. Near the shore a wave took us, that knocked the boat out of water the distance of the throw of a crowbar,* and from the violence with which she struck, nearly all the people who were in her like dead, were roused to consciousness. Finding them- selves near the shore, they began to move on hands and feet, crawling to land into some ravines. There we made fire, parched some of the maize we brought, and found rain water.

Chapter XII: The Indians Bring Us Food (excerpt)

At sunset, the Indians thinking that we had not gone, came to seek us and bring us food; but when they saw us thus, in a plight so different from what it was before, and so extraordinary, they were alarmed and turned back. I went toward them and called, when they returned much frightened. I gave them to understand by signs that our boat had sunk and three of our number had been drowned. There, before them, they saw two of the departed, and we who re- mained were near joining them. The Indians, at sight of what had befallen us, and our state of suffering and melancholy destitution, sat down among us, and from the sorrow and pity they felt, they all began to lament so earnestly that they might have been heard at a dis- tance, and continued so doing more than half an hour. It was strange to see these men, wild and untaught, howling like brutes over our misfortunes. It caused in me as in others, an increase of feeling and a livelier sense of our calamity.

Chapter XII: Our Cure of Some of the Afflicted

That same night of our arrival, some Indians came to Castillo and told him that they had great pain in the head, begging him to cure them. After he made over them the sign of the cross, and commended them to God, they instantly said that all the pain had left, and went to their houses bringing us prickly pears, with a piece of venison, a thing to us little known. As the report of Castillo’s performances spread, many came to us that night sick, that we should heal them, each bringing a piece of venison, until the quantity became so great we knew not where to dispose of it. We gave many thanks to God, for every day went on increasing his compassion and his gifts. After the sick were attended to, they began to dance and sing, making themselves festive, until sunrise ; and because of our arrival, the rejoicing was continued for three days. When these were ended, we asked the Indians about the country farther on, the people we should find in it, and of the subsistence there. They answered us, that throughout all the region prickly pear plants abounded ; but the fruit was now gathered and all the people had gone back to their houses. They said the country was very cold, and there were few skins. Reflecting on this, and that it was already winter, we resolved to pass the season with these Indians. Five days after our arrival, all the Indians went off, taking us with them to gather more prickly pears, where there were other peoples speaking different tongues. After walking five days in great hunger, since on the way was no manner of fruit, we came to a river and put up our houses. We then went to seek the product of certain trees, whjch is like peas. As there are no paths in the country, I was detained some time. The others returned, and coming to look for them in the dark, I got lost. Thank God I found a burning tree, and in the warmth of it passed the cold of that night. In the morning, loading myself with sticks, and taking two brands with me, I returned to seek them. In this manner I wandered five days, ever with my fire and load ; for if the wood had failed me where none could be found, as many parts are with- out any, though I might have sought sticks elsewhere, there would have been no fire to Idndle them. This was all the protection I had against cold, while walking naked as I was born. Going to the low woods near the rivers, I prepared myself for the night, stopping in them before sunset. I made a hole in the ground and threw in fuel which the trees abundantly afforded, col- lected in good quantity from those that were fallen and dry. About the whole I made four fires, in the form of a cross, which I watched and made up from time to time. I also gathered some bundles of the coarse straw that there abounds, with which I covered myself in the hole. In this way I was sheltered at night from cold. On one occasion while I slept, the fire fell upon the straw, when it began to blaze so rapidly that not-withstanding the haste I made to get out of it, I carried some marks on my hair of the danger to which I was exposed. All this while I tasted not a mouthful, nor did I find anything I could eat. My feet were bare and bled a good deal. Through the mercy of God, the wind did not blow from the north in all this time, otherwise I should have died. At the end of the fifth day I arrived on the margin of a river, where I found the Indians, who with the Christians, had considered me dead, supposing that I had been stung by a viper. All were rejoiced to see me, and most so were my companions. They said that up to that time they had struggled with great hunger, which was the cause of their not having sought me. At night, all gave me of their prickly pears, and the next morning we set out for a place where they were in large quantity, with which we satisfied our great craving, the Christ- ians rendering thanks to our Lord that he had ever given us his aid.

Chapter XXIV: Customs of the Indians of That Country (excerpt)

Trom the Island of Malhado to this land, all the Indians whom we saw have the custom from the time in which their wives and themselves pregnant, of not sleeping with them until two years after they have given birth. The children are suckled until the age of twelve years, when they are old enough to get sup- port for themselves. “We asked why they reared them in this manner ; and they said because of the great poverty of the land, it happened many times, as we witnessed, that they were two or three days without eating, sometimes four, and consequently, in seasons of scarcity, the children were allowed to suckle, that they might not famish ; otherwise those who lived would be delicate having httle strength. If any one chance to fall sick in the desert, and cannot keep up with the rest, the Indians leave him to perish, unless it be a son or a brother; him they will assist, even to carrying on their back. It is com- mon among them all to leave their wives when there is no conformity, and directly they connect themselves with whom they please. This is the course of the men who are childless ; those who have children, re- main with their wives and never abandon them.

When they dispute and quarrel in their towns, they strike each other with the fists, fighting until ex- hausted, and then separate. Sometimes they are parted hy the women going between them ; the men never interfere. For no disafljection that arises do they resort to bows and arrows. After they have fought, or had out their dispute, they take their dwell- ings and go into the woods, living apart from each other until their heat has subsided. “When no longer offended and their anger is gone, they return. From that time they are friends as if nothing had happened ; nor is it necessary that any one should mend their friendships, as they in this way again unite them. K those that quarrel are single, they go to some neigh- boring people, and although these should be enemies, they receive them well and welcome them warmly, giving them so largely of what they have, that when their animosity cools, and they return to their town, they go rich. They are all warlike, and have as much strategy for protecting themselves against enemies as they could have were they reared in Italy in continual feuds. When they are in a part of the country where their enemies may attack them, they place their houses on the skirt of a wood, the thickest and most tangled they can find, and near it make a ditch in which they sleep.

Chapter XXXII: The Indians Give Us the Hearts of Deer (except)

In the town where the emeralds were presented to us, the people gave Dorantes over six hundred open hearts of deer.’ They ever keep a good supply of them for food, and we called the place Pueblo de los Corazones. It is the entrance into many provinces on the South sea.^ They who go to look for them and do not enter there, will be lost. On the coast is no maize : the inhabitants eat the powder of rush and of straw, and fish that is caught in the sea from rafts not having canoes. “With grass and straw the women cover their nudity. They are a timid and dejected people…

We were in this town three days. A day’s journey farther was another town, at which the rain fell heavily while we were there, and the river became so swollen we could not cross it, which detained us fifteen days. In this time Castillo saw the buckle of a sword-belt on the neck of an Indian and stitched to it the nail of a horse shoe. He took them, and we asked the native what they were : he answered that they came from heaven. “We questioned him further, as to who had brought them thence : they all responded, that certain men who wore beards like us, had come from heaven and arrived at that river; bringing horses, lances, and swords, and that they had lanced two Indians. In a manner of the utmost indifference we could feign, we asked them what had become of those men : they answered us that they had gone to sea, putting their lances beneath the water, and going themselves also under the water; afterwards that they were seen on the surface going towards the sunset.

For this we gave many thanks to God our Lord. We had before despaired of ever hearing more of Christians. Even yet we were left in great doubt and anxiety, thinking those people were merely persons who had come by sea on discoveries. However, as we had now such exact information, we made greater speed, and as we advanced on our way, the news of the Christians continually grew. We told the natives that we were going in search of that people, to order them not to kill nor make slaves of them, nor take them from their lands, nor do other injustice. Of this the Indians were very glad.

We passed through many territories and found them all vacant : their inhabitants wandered fleeing among the mountains, without daring to have houses or till the earth for fear of Christians. The sight was one of infinite pain to us, a land very fertile and beautiful, abounding in springs and streams, the hamlets deserted and burned, the people thin and weak, all fleeing or in concealment.

As they did not plant, they appeased their keen hunger by eating roots, and the bark of trees. We bore a share in the famine along the whole way ; for poorly could these unfortunates provide for us, themselves being so reduced they looked as though they would willingly die. They brought shawls of those they had concealed because of the Christians, present- ing them to us ; and they related how the Christians, at other times had come through the land destroying and burning the towns, carrying away half the men, and all the women and the boys, while those who had been able to escape were wandering about fugitives. We found them so alarmed they dared not remain any- where. They would not, nor could they till the earth ; but preferred to die rather than live in dread of such cruel usage as they received. Although these showed themselves greatly delighted with us, we feared that on our arrival among those who held the frontier and fought against the Christians, they would treat us badly, and revenge upon us the conduct of their ene- mies ; but when God our Lord was pleased to bring us tbere, they began to dread and respect us as the others had done, and even somewhat more, at which we no httle wondered. Thence it may at once be seen, that to bring all these people to be Christians and to the obedience of the Imperial Majesty, they must be won by kindness, which is a way certain, and no other is.

Chapter XXXIII: We See Traces of Christians (excerpt)

…The day after I overtook four [Christians] on horseback, who were astonished at the sight of me, so strangely habited as I was, and in company with Indians.* They stood staring at me a length of time, so confounded that they neither hailed me nor drew near to make an inquiry…

Chapter XXXIV: Of Sending for the Christians (excerpt)

Five days having elapsed, Andres Dorantes and Alonzo del Castillo arrived with those who had been sent after them. They brought more than six hundred persons of that community, whom the Christians had driven into the forests, and who had wandered in con- cealment over the land. Those who accompanied us so far, had drawn them out, and given them to the Christians, who thereupon dismissed all the others they had brought with them. Upon their coming to where I was, Alcaraz begged that we would summon the people of the towns on the margin of the river, who straggled about under cover of the woods, and order them to fetch us something to eat. This last was unnecessary, the Indians being ever diligent to bring us all they could. Directly we sent our messen- gers to call them, when there came six hundred souls, bringing us all the maize in their possession. They fetched it in certain pots, closed with clay, which they had concealed in the earth. They brought us what- ever else they had ; but we, wishing only to have the provision, gave the rest to the Christians, that they might divide among themselves. After this we had many high words with, them ; for they wished to make slaves of the Indians we brought…

[G]oing with us, [the Indians] feared neither Christians nor lances. Our countrymen became jealous at this, and caused their interpreter to tell the Indians that we were of them, and for a long time we had been lost; that they were the lords of the land who must be obeyed and served, while we were persons of mean condition and small force. The Indians cared little or nothing for what was told them; and conversing among themselves said the Christians lied : that we had come whence the sun rises, and they whence it goes down : we healed the sick, they killed the sound ; that we had come naked and barefooted, while they had arrived in clothing and on horses with lances; that we were not covetous of anything, but all that was given to us, we directly turned to give, remaining with nothing; that the others had theonly purpose to rob whomsoever they found, bestow- ing nothing on any one…

Even to the last, I could not convince the Indians that we were of the Christians…