75 Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland, and Gothic Fiction

Joel Gladd

Figures such as Benjamin Franklin and Phillis Wheatley represent the height of the revolutionary period. Wheatley’s poetry made a powerful argument for the legitimacy of black citizens in the emerging nation. Franklin’s Autobiography offered a program that any citizen should follow in order to make their way in the thirteen colonies.

Charles Brockden Brown belonged to a slightly younger generation. He was born to a Quaker family in Philadelphia and admired Franklin, even publishing a poem dedicated to him in 1789. Franklin died just a few months later and was honored as a scientist, man of letters, and statesman. Wheatley died early, in 1784. Brown began his literary career in the 1790s, just as the newly formed United States was entering a somewhat awkward stage. And Brown wanted to be seen primarily as a literary writer, a novelist even. This was something new entirely. Up to that point in the North American colonies, it wasn’t conceivable to make a living as a poet or novelist.

In the next few weeks we’ll slow down and read Brown’s somewhat bizarre gothic novel Wieland, published in 1798. To make sense of what’s going on, it will help to understand a few contextual elements.

- the novel belongs to the 18th-century “sentimental fiction” tradition;

- inspired in part by Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, it involves intense emotion and a suicide;

- it’s also written in the gothic mode;

- political and religious disruption from the 1790s is part of the plot.

The following lesson will briefly explore each of these areas.

18th-Century Sentimental Fiction

The evolution of the novel is intertwined with a fascinating historical phenomenon that emerged in the 18th-century, known as “sentimentality.” As Ann Weirda Rowland explains in “Sentimental Fiction,” the term “sentimental” belongs to a group of words, including sentimental, sense, sensibility, sensitivity, and sympathy. Many works of literature in the late eighteenth century attempted to cultivate the reader’s “sentiments,” including verse, anthologies, travel narratives, histories, and especially “sentimental novels.”

18th-century sensibility was part of the Enlightenment’s devotion to education, the belief that readers could be shaped and trained by the right kind of reading. This training hinged on the capacity of authors to cultivate a refined and emotional response to specific moral or aesthetic situations. The reader in turn should be able to respond to apply these novelistic/fictional situations to their own life, now with a more refined sensibility.

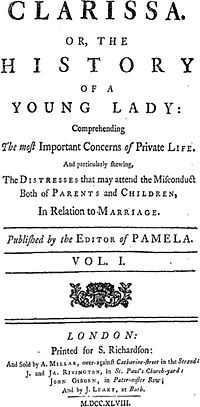

By many accounts, the earliest novel to attempt this form of sentimental education was Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1748), followed later by other British novels such as Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling (1771). In these novels, characters often experience suffering, tears, and tender emotion, verging on melodrama (exaggerated feeling).

In sentimental novels, familial relationships are often a focus. The marriage plot is also common.

Sentimentality didn’t just inform the evolution of the novel, however. Romantic poetry, especially Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads, can be seen as an extension of this sentimental literary tradition.

In poems such as his incredibly moving “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,” Wordsworth portrays deep emotion as the speaker witnesses a scene from earlier in life:

Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.—Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

…

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought,

With many recognitions dim and faint,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity,

The picture of the mind revives again:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years. …

Romantic poetry is largely about deep emotion, as is much of modern poetry, which is heavily inspired by the Romantic tradition.

Extreme Sentiment: Goethe’s Werther and copycat suicide in the late 18th-Century

One of the key characters in Brown’s Wieland commits suicide. This may feel shocking to a contemporary reader who associates early American literature with Puritanism, the founding fathers, etc., but the late 18th-century was not tame.

Sentimental novels often portrayed extreme emotion, showing its limits and the need for restraint (according to the precepts of reason/prudence). We often stumble across fits of insanity in these novels, where madness becomes a means of exposing error and disposing of sinful/irrational characters.

Extreme emotion–even leading to suicide–became a popular staple in sentimental fiction following the far-reaching influence of Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, first published in Germany in 1774. Richard Bell’s chapter, “The Sorrows of Young Readers,” traces the impact of Goethe on North American readers in his book, We Shall Be No More: Suicide and Self-Government in the Newly United States.

Goethe’s sentimental novel was first translated into English in 1779. The narrator was intensely melancholic and infamous for promoting unrestrained self-regard, especially for intense emotion. Written as a series of letters from a 23-year-old artist to a faraway friend, it chronicles his emotional life over a year and a half as he falls hopelessly in love with Charlotte. Charlotte can’t reciprocate Werther’s feelings, but he refuses to move on, and his passion turns into obsession. Over time, he begins to meditate on death to relieve the suffering. Finally, he pens a suicide note to Charlotte, borrows two pistols, and shoots himself.

It was fabulously popular in Europe. The novel was heavily imitated and even led to the production of Werther collectibles: gloves, perfume, etc.[1]

Bell states that it was one of the best-selling novels printed in the U.S. before the War of 1812. British editions often circulated in American cities, and local booksellers produced their own editions based on them. It was printed more than any other novel, except Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple (1794), the first American novel before Brown’s Wieland (1798).

Poets during the Early Republic even adopted the pseudonym “Werter.”

Beginning in the early 1790s, reports of suicides began proliferating, and many accounts noted that Goethe’s novel was found in the person’s room, or that it was inspired by Werther. Local authorities in Europe even began banning the book because they believed it was causing so many copycat suicides.

Example of suicide in contemporary popular culture: 13 Reasons Why

When the Netflix released its immensely popular TV series, 13 Reasons Why, it set off a public debate among parents and public health professions about whether it was appropriate to watch a series that revolved around a protagonist who committed suicide. Shortly after its release, teen suicides spiked in the U.S. The “copycat” nature of the incident suggests eerie parallels with Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther and the late 18th-century copycat suicides.

13 Reasons Why also involves intense emotion and a first-person narration that are hallmarks of the sentimental mode.

Bell summarizes the far-reaching impact on American literature: “No less than fifteen (one-third) of the first forty-five novels written by Americans, all of them published before 1810, depict a character dying by his or her own hand.”[2]

Gothic Fiction

The gothic genre, or gothic mode more generally, is also bound up with the sentimental tradition. In some critical interpretations it can even be seen as an outgrowth of it. Like the sentimental legacy, it is concerned with deep emotion. But gothic fiction was and is obsessed with “dark emotions,” such as agony and suffering.

To stimulate sensibility, authors include stock characters from the sentimental tradition, such as poor and friendless orphans or widows, who are pitted against libertines and the power-obsessed.

Layered over this focus on strong emotion, however, is something distinctly gothic: a preoccupation with a primitive past that spills over into the “enlightened” present. In “Gothic Fiction,” Deidre Shauna Lynch outlines this aspect of the gothic very clearly. In this world, the dead keep speaking, and certain characters hear those voices or are haunted by them.

Readers of gothic fiction (and now, viewers of gothic film) can expect ruins, abandoned houses, haunted castles, and ghosts. The ruins are often acquainted with the aristocratic or clerical aspects of European history. In fact we can read the gothic as partly an attempt to wrestle with the impact and legacy of the aristocratic/clerical/patriarchal past on the present in Western Civilization. More generally, the gothic also focuses on the continued “presence” of the past in the present.

Because the gothic mode is comfortable with slippages in time, it tends to play more freely with its sources as well. Rather than remaining fixated on contemporary events and other literary currents, Lynch’s article explains that gothic authors often turned to unexpected sources of inspiration, such as Cervantes’ Don Quixote. In this sense, the gothic is one of the most “fictional” of all fictional genres–the mode demonstrates the ability of fiction to play with reality and the past in endless ways.

Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland

Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland (1798) is considered America’s first gothic novel. For students of American literary history, it’s important to recognize that it was published during the first chapter of the U.S. republic, often termed the New Republic. Furthermore, beginning around 1795, the Second Great Awakening began to reconfigure American religion and society more generally.

Just as the 18th-century sentimental tradition toyed with the tension between reason and emotion, much of Brown’s novel uses that dynamic to propel the plot forward. But that dynamic is informed by unique forces emerging in the New Republic. The “reason” vs. “emotion” lens that informs much of sentimental fiction in the 18th-century becomes interpreted by Brown in the following manner:

Reason: In Brown’s view, the American founding fathers appealed to “reason” and Enlightenment principles when forging the foundations of the U.S. Enlightenment “reason” sometimes means the classical past, such as Cicero. But a key enlightenment principle was the belief that all knowledge should be derived from one’s individual sense impressions. In Wieland, this “empiricist” aspect of the Enlightenment becomes interrogated.

Religious Enthusiasm/Fanaticism: The novel is also concerned with religious emotion. Brown himself accused some of the founding fathers of mobilizing the “crowds” (the citizens of the Republic) through religious imagery, such as labeling Britain and King George as the “Whore of Babylon,” or referring to the British as devil (Mary Rowlandson’s Narrative was republished with the natives depicted as British solders!). In Brown’s view, the Second Great Awakening fueled this form of religious enthusiasm. In the 1790s, the erosion of social hierarchies in both society and its various religious (largely Protestant) sects led to an eruption of evangelical fervor. In contrast to the Puritan-inspired First Great Awakening (from the early 18th-century), the Second encouraged spontaneous prayer and singing, lay leadership by women and men, and social reforms. Women also became more active participants.

In Brown’s view, the second element does not sit comfortably with the classical Greco-Roman tradition of Cicero, et al, or liberal political thinkers such as John Locke.

But Brown was also skeptical that Enlightenment principles could automatically guarantee truth and virtue. Much of Wieland is about the veracity of sense impressions and the ability of people to be deceived about what they think they perceive. A critical reader will not look for whether “reason” (classicism, enlightenment principles) or “emotion” (religious enthusiasm) win, but rather how Brown uses the gothic-sentimental novel to explore these tensions in the New Republic.

Wieland does, however, belong to the emerging “secular age” of American history, partly inaugurated by Franklin’s Autobiography. In this novel, religious interpretations of ongoing events can no longer be taken for granted. Characters suspect divine influences, but they also consider natural causes and explanations. The mere fact that a character is unsure whether an impression is religiously inspired or derived from actual experience is a secular experience.