37 What Is Psychological Criticism?

Psychological criticism is a critical approach to literature that employs psychological theories to examine aspects of a literary work as a way to better understand both the author’s mind and the characters, themes, and other elements of the text. Thus, the mind is at the center of our target as we learn more about psychological criticism. This approach draws on theories and concepts from psychology, such as psychoanalysis and behavioral psychology, to analyze literary works. It often focuses on the motivations, desires, and conflicts of the characters, and how they are reflected in the structure and themes of the work.

Psychological criticism is a critical approach to literature that employs psychological theories to examine aspects of a literary work as a way to better understand both the author’s mind and the characters, themes, and other elements of the text. Thus, the mind is at the center of our target as we learn more about psychological criticism. This approach draws on theories and concepts from psychology, such as psychoanalysis and behavioral psychology, to analyze literary works. It often focuses on the motivations, desires, and conflicts of the characters, and how they are reflected in the structure and themes of the work.

One of the key principles of psychological criticism is the idea that literature can be used to explore and understand the human psyche, including unconscious and repressed desires and fears. For example, psychoanalytic criticism might explore how the characters in a work of literature are shaped by their early childhood experiences or their relationships with their parents.

Psychological criticism can be applied to any genre of literature, from poetry to novels to plays, and can be used to analyze a wide range of literary works, from classic literature to contemporary bestsellers. It is often used in conjunction with other critical approaches, such as feminist or postcolonial criticism, to explore the ways in which psychological factors intersect with social and cultural factors in the creation and interpretation of literary works.

Learning Objectives

- Deliberate on what approach best suits particular texts and purposes (CLO 1.4)

- Using a literary theory, choose appropriate elements of literature (formal, content, or context) to focus on in support of an interpretation (CLO 2.3)

- Be exposed to a variety of critical strategies through literary theory lenses, such as formalism/New Criticism, reader-response, structuralism, deconstruction, historical and cultural approaches (New Historicism, postcolonial, Marxism), psychological approaches, feminism, and queer theory. (CLO 4.2)

- Learn to make effective choices about applying critical strategies to texts that demonstrate awareness of the strategy’s assumptions and expectations, the text’s literary maneuvers, and the stance one takes in literary interpretation (CLO 4.4)

- Be exposed to the diversity of human experience, thought, politics, and conditions through the application of critical theory (CLO 6.4)

Excerpts from Psychological Criticism Scholarship

I have a confession to make that is likely rooted in my unconscious (or perhaps I am repressing something): I don’t much care for Sigmund Freud. But his psychoanalytic approach underpins psychological criticism in literary studies, so it’s important to be aware of psychoanalytic concepts and how they can be used in literary analysis. We will read a few examples of psychological criticism below, starting with a primary text, a theoretical explanation of psychoanalytic theory, Freud’s “First Lecture” (1920). In this reading, Freud gives a broad outline of the two main tenets of his theories: 1) that our behaviors are often indicators of psychic processes that are unconscious; and 2) that sexual impulses are at the root of mental disorders as well as cultural achievements. In the second and third readings, I share two example of literary criticism, one written by a medical doctor in 1910 that use Freud’s Oedipus complex theories to explicate William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, and the second, a modern example of psychological theory applied to the same play. To appreciate how influential Freud’s theories have been on the study of Hamlet, try a simple JSTOR search with “Freud” and “Hamlet” as your key terms. When I tried this in October 2023, the search yielded 7,420 results.

From “First Lecture” in A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud (1920)

With two of its assertions, psychoanalysis offends the whole world and draws aversion upon itself. One of these assertions offends an intellectual prejudice, the other an aesthetic-moral one. Let us not think too lightly of these prejudices; they are powerful things, remnants of useful, even necessary, developments of mankind. They are retained through powerful affects, and the battle against them is a hard one.

The first of these displeasing assertions of psychoanalysis is this, that the psychic processes are in themselves unconscious, and that those which are conscious are merely isolated acts and parts of the total psychic life. Recollect that we are, on the contrary, accustomed to identify the psychic with the conscious. Consciousness actually means for us the distinguishing characteristic of the psychic life, and psychology is the science of the content of consciousness. Indeed, so obvious does this identification seem to us that we consider its slightest contradiction obvious nonsense, and yet psychoanalysis cannot avoid raising this contradiction; it cannot accept the identity of the conscious with the psychic. Its definition of the psychic affirms that they are processes of the nature of feeling, thinking, willing; and it must assert that there is such a thing as unconscious thinking and unconscious willing. But with this assertion psychoanalysis has alienated, to start with, the sympathy of all friends of sober science, and has laid itself open to the suspicion of being a fantastic mystery study which would build in darkness and fish in murky waters. You, however, ladies and gentlemen, naturally cannot as yet understand what justification I have for stigmatizing as a prejudice so abstract a phrase as this one, that “the psychic is consciousness.” You cannot know what evaluation can have led to the denial of the unconscious, if such a thing really exists, and what advantage may have resulted from this denial. It sounds like a mere argument over words whether one shall say that the psychic coincides with the conscious or whether one shall extend it beyond that, and yet I can assure you that by the acceptance of unconscious processes you have paved the way for a decisively new orientation in the world and in science.

Just as little can you guess how intimate a connection this initial boldness of psychoanalysis has with the one which follows. The next assertion which psychoanalysis proclaims as one of its discoveries, affirms that those instinctive impulses which one can only call sexual in the narrower as well as in the wider sense, play an uncommonly large role in the causation of nervous and mental diseases, and that those impulses are a causation which has never been adequately appreciated. Nay, indeed, psychoanalysis claims that these same sexual impulses have made contributions whose value cannot be overestimated to the highest cultural, artistic and social achievements of the human mind.

According to my experience, the aversion to this conclusion of psychoanalysis is the most significant source of the opposition which it encounters. Would you like to know how we explain this fact? We believe that civilization was forged by the driving force of vital necessity, at the cost of instinct-satisfaction, and that the process is to a large extent constantly repeated anew, since each individual who newly enters the human community repeats the sacrifices of his instinct-satisfaction for the sake of the common good. Among the instinctive forces thus utilized, the sexual impulses play a significant role. They are thereby sublimated, i.e., they are diverted from their sexual goals and directed to ends socially higher and no longer sexual. But this result is unstable. The sexual instincts are poorly tamed. Each individual who wishes to ally himself with the achievements of civilization is exposed to the danger of having his sexual instincts rebel against this sublimation. Society can conceive of no more serious menace to its civilization than would arise through the satisfying of the sexual instincts by their redirection toward their original goals. Society, therefore, does not relish being reminded of this ticklish spot in its origin; it has no interest in having the strength of the sexual instincts recognized and the meaning of the sexual life to the individual clearly delineated. On the contrary, society has taken the course of diverting attention from this whole field. This is the reason why society will not tolerate the above-mentioned results of psychoanalytic research, and would prefer to brand it as aesthetically offensive and morally objectionable or dangerous. Since, however, one cannot attack an ostensibly objective result of scientific inquiry with such objections, the criticism must be translated to an intellectual level if it is to be voiced. But it is a predisposition of human nature to consider an unpleasant idea untrue, and then it is easy to find arguments against it. Society thus brands what is unpleasant as untrue, denying the conclusions of psychoanalysis with logical and pertinent arguments. These arguments originate from affective sources, however, and society holds to these prejudices against all attempts at refutation.

Excerpts from “The Œdipus-Complex as an Explanation of Hamlet’s Mystery: A Study in Motive” by Ernest Jones (1910)

The particular problem of Hamlet, with which this paper is concerned, is intimately related to some of the most frequently recurring problems that are presented in the course of psycho-analysis [sic], and it has thus seemed possible to secure a new point of view from which an answer might be offered to questions that have baffled attempts made along less technical routes. Some of the most competent literary authorities have freely acknowledged the inadequacy of all the solutions of the problem that have up to the present been offered, and from a psychological point of view this inadequacy is still more evident. The aim of the present paper is to expound an hypothesis which Freud some nine years ago suggested in one of the footnotes to his Traumdeutung,·so far as I am aware it has not been critically discussed since its publication. Before attempting this it will be necessary to make a few general remarks about the nature of the problem and the previous solutions that have been offered.

The problem presented by the tragedy of Hamlet is one of peculiar interest in at least two respects. In the first place the play is almost universally considered to be the chief masterpiece of one of the greatest minds the world has known. It probably expresses the core of Shakspere’s [sic] philosophy and outlook on life as no other work of his does, and so far excels all his other writings that many competent critics would place it on an entirely separate level from them. It may be expected, therefore, that anything which will give us the key to the inner meaning of the play will necessarily give us the clue to much of the deeper workings of Shakspere’s mind. In the second place the intrinsic interest of the play is exceedingly great. The central mystery in it, namely the cause of Hamlet’s hesitancy in seeking to obtain revenge for the murder of his father, has well been called the Sphinx of modern Literature. It has given rise to a regiment of hypotheses, and to a large library of critical and controversial literature; this is mainly German and for the most part has grown up in the past fifty years. No review of the literature will here be attempted….

The most important hypotheses that have been put forward are sub-varieties of three main points of view. The first of these sees the difficulty in the performance of the task in Hamlet’s temperament, which is not suited to effective action of any kind; the second sees it in the nature of the task, which is such as to be almost impossible of performance by any one; and the third in some special feature in the nature of the task which renders it peculiarly difficult or repugnant to Hamlet….

No disconnected and meaningless drama could have produced the effects on its audiences that Hamlet has continuously done for the past three centuries. The underlying meaning of the drama may be totally obscure, but that there is one, and one which touches on problems of vital interest to the human heart, is empirically demonstrated by the uniform success with which the drama appeals to the most diverse audiences. To hold the contrary is to deny all the canons of dramatic art accepted since the time of Aristotle. Hamlet as a masterpiece stands or falls by these canons. We are compelled then to take the position that there is some cause for Hamlet’s vacillation which has not yet been fathomed. If this lies neither in his incapacity for action in general, nor in the inordinate difficulty of the task in question, then it must of necessity lie in the third possibility, namely in some special feature of the task that renders it repugnant to him. This conclusion, that Hamlet at heart does not want to carry out the task, seems so obvious that it is hard to see how any critical reader of the play could avoid making it….

It may be asked: why has the poet not put in a clearer light the mental trend we are trying to discover? Strange as it may appear, the answer is the same as in the case of Hamlet himself, namely, he could not, because he was unaware of its nature. We shall later deal with this matter in connection with the relation of the poet to the play. But, if the motive of the play is so obscure, to what can we attribute its powerful effect on the audience? This can only be because the hero’s conflict finds its echo in a similar inner conflict in the mind of the hearer, and the more intense is this already present conflict the greater is the effect of the drama. Again, the hearer himself does not know the inner cause of the conflict in his mind, but experiences only the outer manifestations of it. We thus reach the apparent paradox that the hero, the poet, and the audience are all profoundly moved by feelings due to a conflict of the source of which they are unaware [emphasis added].

The extensive experience of the psycho-analytic researches carried out by Freud and his school during the past twenty years has amply demonstrated that certain kinds of mental processes shew a greater tendency to be “repressed” ( verdrangt) than others. In other words, it is harder for a person to own to himself the existence in his mind of some mental trends than it is of others. In order to gain a correct perspective it is therefore desirable briefly to enquire into the relative frequency with which various sets of mental processes are “repressed.” One might in this connection venture the generalisation that those processes are most likely to be “repressed” by the individual which are most disapproved of by the particular circle of society to whose influence he bas chiefly been subjected. Biologically stated, this law would run: ”That which is inacceptable to the herd becomes inacceptable to the individual unit,” it being understood that the term herd is intended in the sense of the particular circle above defined, which is by no means necessarily the community at large. It is for this reason that moral, social, ethical or religious influences are hardly ever ”repressed,” for as the individual originally received them from his herd, they can never come into conflict with the dicta of the latter. This merely says that a man cannot be ashamed of that which he respects; the apparent exceptions to this need not here be explained. The contrary is equally true, namely that mental trends “repressed” by the individual are those least acceptable to his herd; they are, therefore, those which are, curiously enough, distinguished as “natural” instincts, as contrasted with secondarily acquired mental trends.

It only remains to add the obvious corollary that, as the herd unquestionably selects from the “natural” instincts the sexual ones on which to lay its heaviest ban, so is it the various psycho-sexual trends that most often are “repressed” by the individual. We have here an explanation of the clinical experience that the more intense and the more obscure is a given case of deep mental conflict the more certainly will it be found, on adequate analysis, to centre about a sexual problem. On the surface, of course, this does not appear so, for, by means of various psychological defensive mechanisms, the depression, doubt, and other manifestations of the conflict are transferred on to more acceptable subjects, such as the problems of immortality, future of the world, salvation of the soul, and so on.

Bearing these considerations in mind, let us return to Hamlet. It should now be evident that the conflict hypotheses above mentioned, which see Hamlet’s “natural” instinct for revenge inhibited by an unconscious misgiving of a highly ethical kind, are based on ignorance of what actually happens in real life, for misgivings of this kind are in fact readily accessible to introspection. Hamlet’s self-study would speedily have made him conscious of any such ethical misgivings, and although he might subsequently have ignored them, it would almost certainly have been by the aid of a process of rationalization which would have enabled him to deceive himself into believing that such misgivings were really ill founded; he would in any case have remained conscious of the nature of them. We must therefore invert these hypotheses, and realise that the positive striving for revenge was to him the moral and social one, and that the suppressed negative striving against revenge arose in some hidden source connected with his more personal, “natural” instincts. The former striving has already been considered, and indeed is manifest in every speech in which Hamlet debates the matter; the second is, from its nature, more obscure and has next to be investigated.

This is perhaps most easily done by inquiring more intently into Hamlet’s precise attitude towards the object of his vengeance, Claudius, and towards the crimes that have to be avenged. These are two, Claudius’ incest with the Queen, and his murder of his brother. It is of great importance to note the fundamental difference in Hamlet’s attitude towards these two crimes. Intellectually of course he abhors both, but there can be no question as to which arouses in him the deeper loathing. Whereas the murder of his father evokes in him indignation, and a plain recognition of his obvious duty to avenge it, his mother’s guilty conduct awakes in him the intensest horror. Now, in trying to define Hamlet’s attitude towards his uncle we have to guard against assuming offhand that this is a simple one of mere execration, for there is a possibility of complexity arising in the following way: The uncle has not merely committed each crime, he has committed both crimes, a distinction of considerable importance, for the combination of crimes allows the admittance of a new factor, produced by the possible inter-relation of the two, which prevents the result from being simply one of summation. In addition it has to be borne in mind that the perpetrator of the crimes is a relative, and an exceedingly near relative. The possible inter-relation of the crimes, and the fact that the author of them is an actual member of the family on which they were perpetrated, gives scope for a confusion in their influence on Hamlet’s mind that may be the cause of the very obscurity we are seeking to clarify.

Introduction to “Ophelia’s Desire” by James Marino (2017)

Every great theory is founded on a problem it cannot solve. For psychoanalytic criticism, that problem is Ophelia. Sigmund Freud’s Oedipal reading of Hamlet, mutually constitutive with his reading of Oedipus Rex, initiates the project of Freudian literary interpretation. But that reading must, by its most basic logic, displace Ophelia and render her an anomaly. If the Queen is Hamlet’s primary erotic object, why does he have another love interest? Why such a specific and unusual love interest? The answer that Freud and his disciples offer is that Hamlet’s expressions of love or rage toward Ophelia are displace-ments of his cathexis on the queen. That argument is tautological—one might as easily say that Hamlet displaces his cathected frustration with Ophelia onto the Queen—and requires that some evidence from the text be ignored—“No, good mother,” Hamlet tells the Queen, “here’s metal more attractive”—but the idea of the Queen as Hamlet’s primary affective object remains a standard orthodoxy, common even in feminist Freudians’ readings of Hamlet. Janet Adelman’s Suffocating Mothers, for example, takes the mother-son dyad as central, while Julia Reinhard Lupton and Kenneth Reinhard highlight the symbolic condensation of Ophelia with the Queen. The argument for Ophelia as substitute object may reach its apotheosis in Jacques Lacan’s famous essay on Hamlet, which begins with “that piece of bait named Ophelia” only to use her as an example of Hamlet’s estrangement from his own desire.

Margreta de Grazia’s “Hamlet” without Hamlet has illuminated how the romantic tradition of Hamlet criticism, from which Freud’s own Hamlet criticism derives, focuses on Hamlet’s psychology at the expense of the play’s other characters, who are reduced to figures in the Prince’s individual psychomachia. While psychoanalytic reading objectifies all of Hamlet’s supporting characters, Ophelia is not even allowed to be an object in her own right. Insistently demoted to a secondary or surrogate object, Ophelia becomes mysteriously super-fluous, like a symptom unconnected from its cause. Ophelia is the foundational problem, the nagging flaw in psychoanalytic criticism’s cornerstone. The play becomes very different if Ophelia is decoupled from the Queen and read as an independent and structurally central character, as a primary object of desire, and even as a desiring subject in her own right.

I do not mean to describe the character as a real person, with a fully human psychology; Ophelia is a fiction, constructed from intersecting and contradicting generic expectations. But in those generic terms Ophelia is startlingly unusual, indeed unique, in ways that psychoanalytic criticism has been reluctant to recognize. If stage characters become individuated to the extent that they deviate from established convention, acting against type, then Ophelia is one of William Shakespeare’s most richly individual heroines. And if Shakespeare creates the illusion of interiority, or invites his audience to collaborate in that illusion, by withholding easy explanations of motive, Ophelia’s inner life is rich with mystery. Attention to the elements of Ophelia’s character that psychoanalytic readings resist or repress illuminates the deeper fantasies shaping psychoanalytic discourse. The literary dreams underpinning psychoanalysis are neither simply to be debunked nor to be reconstituted, but to be analyzed. If, as the debates over psychoanalysis over the last three decades have shown, much of Freudian thinking is not science, then it is fantasy; and fantasy, as Freud himself teaches, rewards strict attention. Ophelia, rightly attended, may tell us something about Hamlet, and about Hamlet, that critics have not always wished to know. To see Ophelia clearly would also make it clear how closely Hamlet resembles her and how faithfully his tragic arc follows hers.

Beyond Freud: Applying Psychological Theories to Literary Texts

Fortunately, we are not limited to Freud when we engage in psychological criticism. We can choose any psychological theory. Here are just a few you might consider:

- Carl Jung’s archetypes: humans have a collective unconscious that includes universal archetypes such as the shadow, the persona, and the anima/us.

- B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism: all behaviors are learned through conditioning.

- Jacques Lacan’s conception of the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic.

- Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development: describes the effects of social development across a person’s lifespan.

- Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development: explains how people develop moral reasoning.

- Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: people’s basic needs need to be met before they can pursue more advanced emotional and intellectual needs.

- Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief: a framework for understanding loss.

- Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth Bancroft Clark’s work on internalized racism.

- Derald Wing Sue and David Sue’s work with Indigenous spiritual frameworks and mental health.

It’s important to differentiate this type of criticism from looking at “mental health” or considering how the poem affects our emotions. When we are exploring how a poem makes us feel, this is subjective reader response, not psychological criticism. Psychological criticism involves analyzing a literary work through the lens of a psychological theory, exploring characters’ motivations, behaviors, and the author’s psychological influences. Here are a few approaches you might take to apply psychological criticism to a text:

- Psychological Theories: Familiarize yourself with the basics of key psychological theories, such as Freudian psychoanalysis, Jungian archetypes, or cognitive psychology. This knowledge provides a foundation for interpreting characters and their actions. It’s best to choose one particular theory to use in your analysis.

- Author’s Background: Research the author’s life and background. Explore how their personal experiences, relationships, and psychological state might have influenced the creation of characters or the overall themes of the text. Also consider what unconscious desires or fears might be present in the text. How can the text serve as a window to the author’s mind? The fictional novel Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell uses the text of Hamlet along with the few facts that are known about Shakespeare’s life to consider how the play could be read as an expression of the author’s grief at losing his 11-year-old son.

- Character Analysis: Examine characters’ personalities, motivations, and conflicts. Consider how their experiences, desires, and fears influence their actions within the narrative. Look for signs of psychological trauma, defense mechanisms, or unconscious desires. You can see an example of this in the two literary articles above, where the authors consider Hamlet’s and Ophelia’s motivations and conflicts.

- Symbolism and Imagery: Analyze symbols and imagery in the text. Understand how these elements may represent psychological concepts or emotions. For example, a recurring symbol might represent a character’s repressed desires or fears.

- Themes and Motifs: Identify recurring themes and motifs. Explore how these elements reflect psychological concepts or theories. For instance, a theme of isolation might be analyzed in terms of its impact on characters’ mental states. An example of a motif in Hamlet would be the recurring ghost.

- Archetypal Analysis: Jungian analysis is one of my personal favorite approaches to take to texts. You can apply archetypal psychology to identify universal symbols or patterns in characters. Carl Jung’s archetypes, such as the persona, shadow, or anima/animus, can provide insights into the deeper layers of character development.

- Psychological Trajectories: Trace the psychological development of characters throughout the narrative. Identify key moments or events that shape their personalities and behaviors. Consider how these trajectories contribute to the overall psychological impact of the text.

- Psychoanalytic Concepts: If relevant, apply psychoanalytic concepts such as id, ego, and superego. Explore how characters navigate internal conflicts or succumb to unconscious desires. Freudian analysis can uncover hidden motivations and tensions.

Because psychological criticism involves interpretation, there may be multiple valid perspectives on a single text. When using this critical method, I recommend focusing on a single psychological approach (e.g. choose Freud or Jung; don’t try to do both).

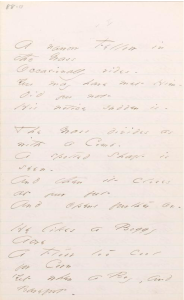

Let’s practice with Emily Dickinson’s poem “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass,” using Freud’s psychoanalytic theories as our psychological approach. Read the poem first, then use the questions below to guide your interpretation of the poem.

A Narrow Fellow in the Grass* (1865)

A narrow fellow in the grass

Occasionally rides:

You may have met him, —did you not,

His notice sudden is.

The grass divides as with a comb,

A spotted shaft is seen;

And then it closes at your feet

And opens further on.

He likes a boggy acre.

A floor too cool for corn.

Yet when a child, and barefoot,

I more than once, at morn,

Have passed, I thought, a whip-lash

Unbraiding in the Sun.—

When, stooping to secure it,

It wrinkled, and was gone.

Several of nature’s people

I know, and they know me;

I feel for them a transport

Of cordiality;

But never met this fellow,

Attended or alone,

Without a tighter breathing,

And zero at the bone.

*I’ve used the “corrected” version published in 1865. Here is a link to the transcribed version from the original manuscript.

Here are a few questions to consider as you apply Freudian psychoanalysis to the poem.

- Imagery and Motifs: This poem is one of just 10 Emily Dickinson poems published during her lifetime. The editor chose a different title for the poem: “The Snake”. How does adding this title change the reader’s experience with the poem? Which words in the poem seem odd in the context of this title? In a Freudian reading of the poem, what would the snake (if it is a snake) represent?

- Repression and Symbolism: How might the “narrow Fellow in the Grass” symbolize repressed desires or memories in the speaker’s subconscious? What elements in the poem suggest a hidden, perhaps uncomfortable, aspect of the speaker’s psyche?

- Penis Envy: In Freudian theory, penis envy refers to a girl’s desire for male genitalia. How does this concept apply to the poem? Dickinson’s handwritten version of the poem says “boy” instead of “child” in line 11. How does this change impact how we read the poem?

- Unconscious Fears and Anxiety (Zero at the Bone): The closing lines mention a “tighter Breathing” and feeling “Zero at the Bone.” How can Freud’s ideas about the unconscious and anxiety be applied here? What might the encounter with the Fellow reveal about the speaker’s hidden fears or anxieties, and how does it impact the speaker on a deep, unconscious level?

- Punctuation: The manuscript versions of this poem do not use normal punctuation conventions. Instead, the author uses a dash. How does this change our reading of the poem? What does her use of dashes imply about her psychological state?

As with New Historicism, you’ll need to do some research and cite a source for the psychological theory you apply. Introduce the psychological theory, then use it to analyze the poem. Make sure to support your analysis with specific textual evidence from the poem. Use line numbers to refer to specific parts of the text.

You’ll want to come up with a thesis statement that you can support with the evidence you’ve found.

Freudian Analysis Thesis Statement: In Emily Dickinson’s poem “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass,” the encounter with a snake serves as a symbolic manifestation of repressed desires, unconscious fears, and penis envy, offering a Freudian exploration of the complex interplay between the conscious and unconscious mind.

How would this thesis statement be different if you had chosen a different approach–for example, Erik Erikson’s theory of child development? How does this analysis differ from a New Criticism approach? Do you think that a Freudian approach is useful in helping readers to appreciate this poem?

The Limitations of Psychological Criticism

While psychological criticism provides valuable insights into the human psyche and enriches our understanding of literary works, it also has its limitations. Here are a few:

- Subjectivity: Psychological interpretations often rely on subjective analysis, as different readers may perceive and interpret psychological elements in a text differently. The lack of objective criteria can make it challenging to establish a universally accepted interpretation. However, using an established psychological theory can help to address this concern.

- Authorial Intent: Inferring an author’s psychological state or intentions based on their work can be speculative. Without direct evidence from the author about their psychological motivations, interpretations may be subjective and open to debate.

- Overemphasis on Individual Psychology: Psychological criticism may focus heavily on individual psychology and neglect broader social, cultural, or historical contexts that also influence literature. This narrow focus may oversimplify the complexity of human experience.

- Stereotyping Characters: Applying psychological theories to characters may lead to oversimplified or stereotypical portrayals. Characters might be reduced to representing specific psychological concepts, overlooking their multifaceted nature. Consider the scholarly readings above and how Ophelia has traditionally been read as an accessory to Hamlet rather than as a fully developed character in her own right.

- Neglect of Formal Elements: Psychological criticism may sometimes neglect formal elements of a text, such as structure, style, and language, in favor of exploring psychological aspects. This oversight can limit a comprehensive understanding of the literary work.

- Inconsistency in Psychoanalytic Theories: Different psychoanalytic theories exist, and scholars may apply competing frameworks, leading to inconsistent interpretations. For example, a Freudian interpretation may differ significantly from a Jungian analysis.

- Exclusion of Reader Response: While psychological criticism often explores the author’s psyche, it may not give sufficient attention to the diverse psychological responses of readers. The reader’s own psychology and experiences contribute to the meaning derived from a text. In formal literary criticism, as we noted above, this type of approach is considered to be subjective reader response, but it might be an interesting area of inquiry that is traditionally excluded from psychological criticism approaches.

- Neglect of Positive Aspects: Psychological criticism may sometimes focus too much on negative or pathological aspects of characters, overlooking positive psychological dimensions and the potential for growth and redemption within the narrative (we care a lot more about what’s wrong with Hamlet than what’s right with him).

Acknowledging these limitations helps balance the use of psychological criticism with other literary approaches, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of a literary work.

Psychological Criticism Scholars

There is considerable overlap in psychological criticism scholarship. With this type of approach, some psychologists/psychiatrists use literary texts to demonstrate or explicate psychological theories, while some literary scholars use psychological theories to interpret works. Here are a few better-known literary scholars who practice this type of criticism:

- Sigmund Freud, who used Greek literature to develop his theories about the psyche

- Carl Jung, whose ideas of the archetypes are fascinating

- Alfred Adler, a student of Freud’s who particularly focused on literature and psychoanalysis

- Jacques Lacan, a French psychoanalyst whose ideas of the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic provide interesting insights into literary texts.

Further Reading

- Adler, Alfred. The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler. Ed. Heinz and Rowena R. Ansbacher. New York: Anchor Books, 1978. Print.

- Çakırtaş, Önder, ed. Literature and Psychology: Writing, Trauma and the Self. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018.

- Eagleton, Terry. “Psychoanalysis.” Literary Theory: An Introduction. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1983. 151-193. Print

- Freud. Sigmund. The Ego and the Id. https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_SE_Ego_Id_complete.pdf Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

–A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Project Gutenberg eBook #38219. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/38219/pg38219.txt

–The Interpretation of Dreams. 1900. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Freud/Dreams/dreams.pdf - Hart, F. Elizabeth (Faith Elizabeth). “The Epistemology of Cognitive Literary Studies.” Philosophy and Literature, vol. 25 no. 2, 2001, p. 314-334. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/phl.2001.0031.

- Ingarden, Roman, and John Fizer. “Psychologism and Psychology in Literary Scholarship.” New Literary History, vol. 5, no. 2, 1974, pp. 213–23. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/468392. Accessed 26 Oct. 2023.

- Jones, Ernest. “The Œdipus-Complex as an Explanation of Hamlet’s Mystery: A Study in Motive.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 21, no. 1, 1910, pp. 72–113. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1412950. Accessed 26 Oct. 2023.

-

Knapp, John V. “New Psychologies in Literary Criticism.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2006, pp. 102–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41209945. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

- Marino, James J. “Ophelia’s Desire.” ELH, vol. 84, no. 4, 2017, pp. 817–39. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26797511. Accessed 26 Oct. 2023.

- Willburn, David. “Reading After Freud.” Contemporary Literary Theory. Ed. G. Douglas Atkins and Laura Morrow. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1989. 158-179.

-

Shupe, Donald R. “Representation versus Detection as a Model for Psychological Criticism.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 34, no. 4, 1976, pp. 431–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/430577. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

- Zizek, Slavoj. How to Read Lacan. New York: Norton, 2007.