6 Time Management Strategies

How to Manage Time

In this next section you will learn about managing time and prioritizing tasks. This is not only a valuable skill for pursuing an education, but it can become an ability that follows you through the rest of your life, especially if your career takes you into a leadership role.

Figure. An online calendar is a very useful tool for keeping track of classes, meetings, and other events. Most learning management systems contain these features, or you can use a calendar application.

Analysis Question

Read each statement in the brief self-evaluation tool below, and check the answer that best applies to you. There are no right or wrong answers.

| Always | Usually | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | |

| I like to be given strict deadlines for each task. It helps me stay organized and on track. | |||||

| I would rather be 15 minutes early than 1 minute late. | |||||

| I like to improvise instead of planning everything out ahead of time. | |||||

| I prefer to be able to manage when and how I do each task. | |||||

| I have a difficult time estimating how long a task will take. | |||||

| I have more motivation when there is an upcoming deadline. It helps me focus. | |||||

| I have difficulty keeping priorities in the most beneficial order. |

Table 3.3

This exercise is intended to help you recognize some things about your own time management style. The important part is for you to identify any areas where you might be able to improve and to find solutions for them. This chapter will provide some solutions, but there are many others that can be found by researching time management strategies.

After you have decided your best response to each statement, think about what they may mean in regard to potential strengths and/or challenges for you when it comes to time management in college. If you are a person that likes strict deadlines, what would you do if you took a course that only had one large paper due at the end? Would you set yourself a series of mini deadlines that made you more comfortable and that kept things moving along for you? Or, if you have difficulty prioritizing tasks, would it help you to make a list of the tasks to do and order them, so you know which ones must be finished first?

Strategies for Managing Time

The simplest way to manage your time is to accurately plan for how much time it will take to do each task, and then set aside that amount of time. How you divide the time is up to you. If it is going to take you five hours to study for a final exam, you can plan to spread it over five days, with an hour each night, or you can plan on two hours one night and three hours the next. What you would not want to do is plan on studying only a few hours the night before the exam and find that you fell very short on the time you estimated you would need. If that were to happen, you would have run out of time before finishing, with no way to go back and change your decision. In this kind of situation, you might even be tempted to “pull an all-nighter,” which is a phrase that has been used among college students for decades. In essence it means going without sleep for the entire night and using that time to finish an assignment. While this method of trying to make up for poor planning is common enough to have a name, rarely does it produce the best work.

Activity

Many people are not truly aware of how they actually spend their time. They make assumptions about how much time it takes to do certain things, but they never really take an accurate account.

In this activity, write down all the things you think you will do tomorrow, and estimate the time you will spend doing each. Then track each thing you have written down to see how accurate your estimates were.

Obviously, you will not want to get caught up in too much tedious detail, but you will want to cover the main activities of your day—for example, working, eating, driving, shopping, gaming, being engaged in entertainment, etc.

After you have completed this activity for a single day, you may consider doing it for an entire week so that you are certain to include all of your activities.

Many people that take this sort of personal assessment of their time are often surprised by the results. Some even make lifestyle changes based on it.

| Activity | Estimated Time | Actual Time |

| Practice Quiz | 5 minutes | 15 minutes |

| Lab Conclusions | 20 minutes | 35 minutes |

| Food shopping | 45 minutes | 30 minutes |

| Drive to work | 20 minutes | 20 minutes |

| Physical Therapy | 1 hour | 50 minutes |

Table 3.4 Sample Time Estimate Table

Of all the parts of time management, accurately predicting how long a task will take is usually the most difficult—and the most elusive. Part of the problem comes from the fact that most of us are not very accurate timekeepers, especially when we are busy applying ourselves to a task. The other issue that makes it so difficult to accurately estimate time on task is that our estimations must also account for things like interruptions or unforeseen problems that cause delays.?

When it comes to academic activities, many tasks can be dependent upon the completion of other things first, or the time a task takes can vary from one instance to another, both of which add to the complexity and difficulty of estimating how much time and effort are required.

For example, if an instructor assigned three chapters of reading, you would not really have any idea how long each chapter might take to read until you looked at them. The first chapter might be 30 pages long while the second is 45. The third chapter could be only 20 pages but made up mostly of charts and graphs for you to compare. By page count, it might seem that the third chapter would take the least amount of time, but actually studying charts and graphs to gather information can take longer than regular reading.?

To make matters even more difficult, when it comes to estimating time on task for something as common as reading, not all reading takes the same amount of time. Fiction, for example, is usually a faster read than a technical manual. But something like the novel Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce is considered so difficult that most readers never finish it.

Knowing Yourself

While you can find all sorts of estimates online as to how long a certain task may take, it is important to know these are only averages. People read at different speeds, people write at different speeds, and those numbers even change for each individual depending on the environment.

If you are trying to read in surroundings that have distractions (e.g., conversations, phone calls, etc.), reading 10 pages can take you a lot longer than if you are reading in a quiet area. By the same token, you may be reading in a quiet environment (e.g., in bed after everyone in the house has gone to sleep), but if you are tired, your attention and retention may not be what it would be if you were refreshed.

In essence, the only way you are going to be able to manage your time accurately is to know yourself and to know how long it takes you to do each task. But where to begin?

Below, you will find a table of common college academic activities. This list has been compiled from a large number of different sources, including colleges, publishers, and professional educators, to help students estimate their own time on tasks. The purpose of this table is to both give you a place to begin in your estimates and to illustrate how different factors can impact the actual time spent.

You will notice that beside each task there is a column for the unit, followed by the average time on task, and a column for notes. The unit is whatever is being measured (e.g., pages read, pages written, etc.), and the time on task is an average time it takes students to do these tasks. It is important to pay attention to the notes column, because there you will find factors that influence the time on task. These factors can dramatically change the amount of time the activity takes.

| Time on Task | |||

| Activity | Unit | Time on task | Notes |

| General academic reading (textbook, professional journals) | 1 page | 5–7 minutes | Be aware that your personal reading speed may differ and may change over time. |

| Technical reading (math, charts and data) | 1 page | 10–15 minutes | Be aware that your personal reading speed may differ and may change over time. |

| Simple Quiz or homework question: short answer—oriented toward recall or identification type answers | Per question | 1–2 minutes | Complexity of question will greatly influence the time required. |

| Complex Quiz or homework question: short answer—oriented toward application, evaluation, or synthesis of knowledge | Per question | 2–3 minutes | Complexity of question will greatly influence the time required. |

| Math problem sets, complex | Per question | 15 minutes | For example, algebra, complex equations, financial calculations |

| Writing: short, no research | Per page | 60 minutes | Short essays, single-topic writing assignments, summaries, freewriting assignments, journaling—includes drafting, writing, proofing, and finalizing |

| Writing: research paper | Per page | 105 minutes | Includes research time, drafting, editing, proofing, and finalizing (built into per-page calculation) |

| Study for quiz | Per chapter | 60 minutes | 45–90 minutes per chapter, depending upon complexity of material |

| Study for exam | Per exam | 90 minutes | 1–2 hours, depending upon complexity of material |

Table 3.5 Time on task for common college activities.

Again, these are averages, and it does not mean anything if your times are a little slower or a little faster. There is no “right amount of time,” only the time that it takes you to do something so you can accurately plan and manage your time.

There is also another element to look for in the table. These are differentiations in the similar activities that will also affect the time you spend. A good example of this can be found in the first four rows. Each of these activities involves reading, but you can see that depending on the material being read and its complexity, the time spent can vary greatly. Not only do these differences in time account for the different types of materials you might read (as you found in the comparative reading exercise earlier in this chapter), but also they also take into consideration the time needed to think about what you are reading to truly understand and comprehend what it is saying.

Enhanced Strategies

Over the years, people have developed a number of different strategies to manage time and tasks. Some of the strategies have proven to be effective and helpful, while others have been deemed not as useful.

The good news is that the approaches that do not work very well or do not really help in managing time do not get passed along very often. But others, those which people find of value, do. What follows here are three unique strategies that have become staples of time management. While not everyone will find that all three work for them in every situation, enough people have found them beneficial to pass them along with high recommendations.

Daily Top Three

The idea behind the daily top three approach is that you determine which three things are the most important to finish that day, and these become the tasks that you complete. It is a very simple technique that is effective because each day you are finishing tasks and removing them from your list. Even if you took one day off a week and completed no tasks on that particular day, a daily top three strategy would have you finishing 18 tasks in the course of a single week.

Pomodoro Technique

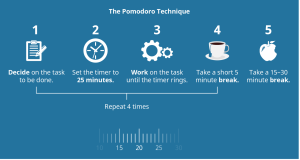

Figure 3.14 The Pomodoro Technique is named after a type of kitchen timer, but you can use any clock or countdown timer. (Marco Verch /Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0))

The Pomodoro Technique was developed by Francesco Cirillo. The basic concept is to use a timer to set work intervals that are followed by a short break. The intervals are usually about 25 minutes long and are called pomodoros, which comes from the Italian word for tomato because Cirillo used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer to keep track of the intervals.

In the original technique there are six steps:

- Decide on the task to be done.

- Set the timer to the desired interval.

- Work on the task.

- When the timer goes off, put a check mark on a piece of paper.

- If you have fewer than four check marks, take a short break (3–5 minutes), then go to Step 1 or 2 (whichever is appropriate).

- After four pomodoros, take a longer break (15–30 minutes), reset your check mark count to zero, and then go to Step 1 or 2.

Figure 3.15 The Pomodoro Technique contains five defined steps.

There are several reasons this technique is deemed effective for many people. One is the benefit that is derived from quick cycles of work and short breaks. This helps reduce mental fatigue and the lack of productivity caused by it. Another is that it tends to encourage practitioners to break tasks down to things that can be completed in about 25 minutes, which is something that is usually manageable from the perspective of time available. It is much easier to squeeze in three 25-minute sessions of work time during the day than it is to set aside a 75- minute block of time.

Eat the Frog

Of our three quick strategies, eat the frog probably has the strangest name and may not sound the most inviting. The name comes from a famous quote, attributed to Mark Twain: “Eat a live frog first thing in the morning and nothing worse will happen to you the rest of the day.” Eat the Frog is also the title of a best-selling book by Brian Tracy that deals with time management and avoiding procrastination.

How this applies to time and task management is based on the concept that if a person takes care of the biggest or most unpleasant task first, everything else will be easier after that.

Although stated in a humorous way, there is a good deal of truth in this. First, we greatly underestimate how much worry can impact our performance. If you are continually distracted by anxiety over a task you are dreading, it can affect the task you are working on at the time. Second, not only will you have a sense of accomplishment and relief when the task you are concerned with is finished and out of the way, but other tasks will seem lighter and not as difficult.

Breaking Down the Steps and Spreading Them over Shorter Work Periods

Above, you read about several different tried-and-tested strategies for effective time management—approaches that have become staples in the professional world. In this section you will read about two more creative techniques that combine elements from these other methods to handle tasks when time is scarce and long periods of time are a luxury you just do not have.

The concept behind this strategy is to break tasks into smaller, more manageable units that do not require as much time to complete. As an illustration of how this might work, imagine that you are assigned a two-page paper that is to include references. You estimate that to complete the paper—start to finish—would take you between four and a half and five hours. You look at your calendar over the next week and see that there simply are no open five-hour blocks (unless you decided to only get three hours of sleep one night). Rightly so, you decide that going without sleep is not a good option. While looking at your calendar, you do see that you can squeeze in an hour or so every night. Instead of trying to write the entire paper in one sitting, you break it up into much smaller components as shown in the table below:

Breaking Down Projects into Manageable-Sized Tasks

| Day/Time | Task | Time |

| Monday, 6:00 p.m. | Write outline; look for references. | 60 minutes |

| Tuesday, 6:00 p.m. | Research references to support outline; look for good quotes. | 60 minutes |

| Wednesday, 7:00 p.m. | Write paper introduction and first page draft. | 60 minutes |

| Thursday, 6:00 p.m. | Write second page and closing draft. | 60 minutes |

| Friday, 5:00 p.m. | Rewrite and polish final draft. | 60 minutes |

| Saturday, 10:00 a.m. | Only if needed—finish or polish final draft. | 60 minutes? |

Table 3.8

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| 8:00–10:00 | Work | Work | |||||

| 10:00–12:00 | Algebra | Work | Algebra | Work | Algebra | 10 a.m.–11 a.m. Only if needed | Work |

| 12:00–2:00 | Lunch/study | 1 p.m. English Comp | Lunch/study | 1 p.m. English Comp | Lunch/study | Family picnic | Work |

| 2:00–4:00 | History | English Comp | History | English Comp | History | Family picnic | |

| 4:00–6:00 | Study for Algebra quiz. | Grocery | Study for History exam. | Study for History exam. | 5 p.m.–6 p.m. Rewrite and polish final draft. | Family picnic | Laundry |

| 6:00–7:00 | Write outline; look for references. | Research references to support outline; look for good quotes. | Research presentation project. | Write second page and closing draft | Create presentation. | Meet with Darcy. | Prepare school stuff for next week. |

| 7:00–8:00 | Free time | Free time | Write paper introduction and first page draft. | Research presentation project. | Create presentation. | Free time |

Table 3.9

While this is a simple example, you can see how it would redistribute tasks to fit your available time in a way that would make completing the paper possible. In fact, if your time constraints were even more rigid, it would be possible to break these divided tasks down even further. You could use a variation of the Pomodoro Technique and write for three 20-minute segments each day at different times. The key is to look for ways to break down the entire task into smaller steps and spread them out to fit your schedule.

Analyzing Your Schedule and Creating Time to Work

Of all the strategies covered in this chapter, this one may require the most discipline, but it can also be the most beneficial in time management. The fact is most of us waste time throughout the day. Some of it is due to a lack of awareness, but it can also be caused by the constraints of our current schedules. An example of this is when we have 15 to 20 minutes before we must leave to go somewhere. We don’t do anything with that time because we are focused on leaving or where we are going, and we might not be organized enough to accomplish something in that short of a time period. In fact, a good deal of our 24- hour days are spent a few minutes at a time waiting for the next thing scheduled to occur. These small units of time add up to a fair amount each day.

The intent of this strategy is to recapture those lost moments and use them to your advantage. This may take careful observation and consideration on your part, but the results of using this as a method of time management are more than worth it.

The first step is to look for those periods of time that are wasted or that can be repurposed. In order to identify them, you will need to pay attention to what you do throughout the day and how much time you spend doing it. The example of waiting for the next thing in your schedule has already been given, but there are many others. How much time do you spend in activities after you have really finished doing them but are still lingering because you have not begun to do something else (e.g., letting the next episode play while binge-watching, reading social media posts or waiting for someone to reply, surfing the Internet, etc.)? You might be surprised to learn how much time you use up each day by just adding a few unproductive minutes here and there.

If you set a limit on how much time you spend on each activity, you might find that you can recapture time to do other things. An example of this would be limiting yourself to reading news for 30 minutes. Instead of reading the main things that interest you and then spending an additional amount of time just looking at things that you are only casually interested in because that is what you are doing at the moment, you could stop after a certain allotted period and use the extra time you have gained on something else.

After you identify periods of lost time, the next step will be to envision how you might restructure your activities to bring those extra minutes together into useful blocks of time. Using the following scenario as an illustration, we will see how this could be accomplished.

Figure 3.16 Sarah has to balance a lot of obligations.

On Tuesday nights, Sarah has a routine: After work, she does her shopping for the week (2 hours driving and shopping) and then prepares and eats dinner (1 hour). After dinner, she spends time on homework (1 hour) and catching up with friends, reading the news, and other Internet activities (1 hour), and then she watches television or reads before going to bed (1 hour). While it may seem that there is very little room for improvement in her schedule without cutting out something she enjoys, limiting the amount of time she spends on each activity and rethinking how she goes about each task can make a significant difference.

In this story, Sarah’s Tuesday-night routine includes coming home from work, taking stock of which items in her home she might need to purchase, and then driving to the store. While at the store, she spends time picking out and selecting groceries as she plans for meals she will eat during the rest of the week. Then, after making her purchases, she drives home. Instead, if she took the time to make a list and plan for what she needed at the store before she arrived, she would not spend as much time looking for inspiration in each aisle. Also, if she had a prepared list, not only could she quickly pick up each item, but she could stop at the store on the way home from work, thus cutting out the extra travel time. If purchasing what she needed took 30 minutes less because she was more organized and she cut out an additional 20 minutes of travel time by saving the extra trip to the store from her house, she could recapture a significant amount of her Tuesday evening. If she then limited the time she spent catching up with friends and such to 30 minutes or maybe did some of that while she prepared dinner, she would find that she had added almost an extra hour and a half to the time available to her on that evening, without cutting out anything she needed to do or enjoys. If she decided to spend her time on study or homework, this would more than double the time she previously had available in her schedule for homework.

This chapter is from College Success, “How to Manage Time” and “Enhanced Strategies for Time and Task Management.” CC-BY 4.0.