17 Mircea Eliade: Sacred Spaces

Reading: “Introduction” and “Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred” from The Sacred and the Profane.

“The hearer of myth, regardless of his level of culture, when he is listening to a myth, forgets, as it were, his particular situation and is projected into another world, into another universe which is no longer his poor little universe of every day. . . . The myths are true because they are sacred, because they tell him about sacred beings and events. Consequently, in reciting or listening to a myth, one resumes contact with the sacred and with reality, and in so doing one transcends the profane condition, the “historical situation.” In other words one goes beyond the temporal condition and the dull self-sufficiency which is the lot of every human being simply because every human being is “ignorant” — in the sense that he is identifying himself, and Reality, with his own particular situation. And ignorance is, first of all, this false identification of Reality with what each one of us appears to be or to possess.” (Mircea Eliade, Images and Symbols, 1952, 59).

Vocabulary

- Sacred: Eliade p. 10 “the opposite of the profane,” a higher spiritual reality

- profane: in Eliade, belonging to the ordinary world

- hierophany: “The act of manifestation of the sacred” p. 11

- axis mundi: center of the world (mountain, tree, temple)

Background

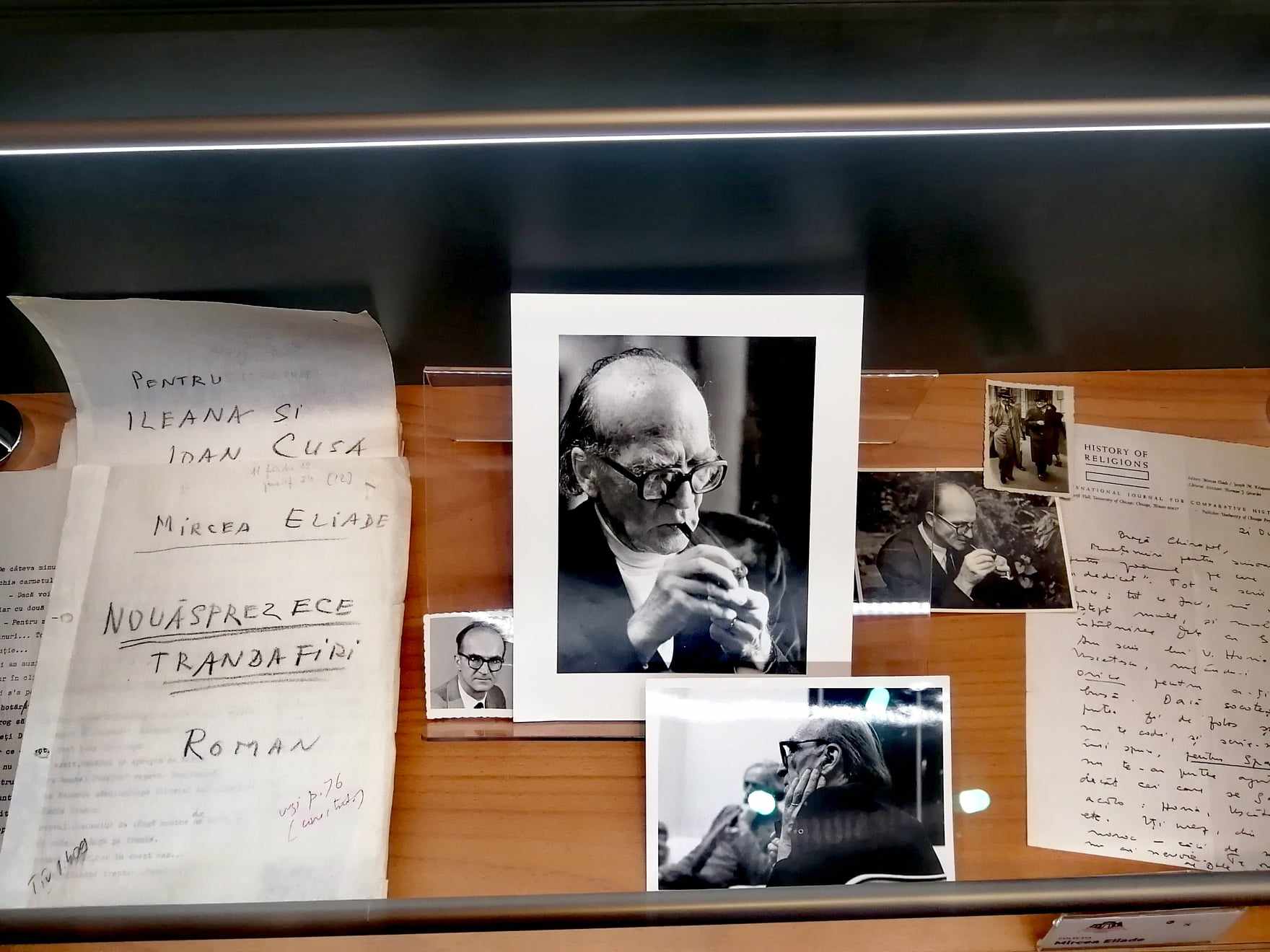

Mircea Eliade was a Romanian religious historian and prolific author who wrote novels in his native Romanian and scholarly works in French. His belief that religion at its heart could not be deconstructed or reduced to anything less than something he called “the sacred” was controversial but influential. Like Jung, Eliade believed in universal archetypal symbols across world cultures. According to Eliade, myths both recall a primordial time and help modern humans to deal with existential crises. His critics often attacked him, both for his political views during the second World War and for his “unscientific” approach to myth as a scholar.

Summary

In the Sacred and the Profane, Eliade outlines his approach to myth as an expression of what he terms “the sacred,” which exists in opposition to the ordinary or “profane” world. He writes, sacred and profane are two modes of being in the world, two existential situations assumed by man in the course of his history. These modes of being in the world are not of concern only to the history of religions or to sociology; they are not the object only of historical, sociological, or ethnological study. In the last analysis, the sacred and profane modes of being depend upon the different positions that man has conquered in the cosmos; hence they are of concern both to the philosopher and to anyone seeking to discover the possible dimensions of human existence” (15).

Myths rely on symbols that include sacred spaces. Eliade explores a variety of spaces that also discussed in Leeming, including the axis mundi, or center, the City, places of sacrifice, and places of worship. While different cultures experience the sacred in different ways, Eliade argues that the experience itself is universal: “we could say that the experience of sacred space makes possible the “founding of the world”: where the sacred manifests itself in space, the real unveils itself, the world comes into existence” (63).