16 Exploring Hindu Culture: Ancient Wisdom and Living Traditions

“If I were asked to define the Hindu creed, I should simply say: Search after truth through non-violent means. A man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu. Hinduism is a relentless pursuit after truth… Hinduism is the religion of truth. Truth is God. Denial of God we have known. Denial of truth we have not known.” — Mahatma Gandhi, Young India

Introduction: India in Global and Cultural Context

In the sacred waters of the Ganges River, millions of pilgrims gather each year to participate in rituals that stretch back over four millennia, making Hinduism one of humanity’s oldest continuous religious traditions. Unlike many world religions with clearly defined founders and central doctrines, Hinduism represents a rich tapestry of beliefs, practices, and philosophical traditions that have evolved organically across the Indian subcontinent. This ancient tradition—more accurately understood as a family of related religions—encompasses everything from elaborate temple rituals to profound philosophical inquiries about the nature of reality itself.

What makes Hinduism particularly remarkable is its extraordinary capacity for diversity and synthesis. While geographically rooted in the Indian subcontinent and culturally connected to Sanskrit traditions, Hinduism has demonstrated remarkable adaptability, incorporating local customs and beliefs while maintaining core spiritual insights. This flexibility reflects both the distinctive features of Hindu civilization and the complex ways religious traditions evolve through contact with diverse cultures and changing historical circumstances.

As Gandhi’s quote suggests, Hinduism has always prioritized the search for truth over rigid orthodoxy, creating space for atheists and polytheists, ascetics and householders, all under the same vast spiritual umbrella. This inclusivity has allowed Hindu thought to survive and flourish through millennia of political upheaval, foreign invasion, and cultural transformation while contributing fundamental concepts—dharma, karma, yoga, meditation—that continue to shape global spirituality today.

Historical Foundations and Cultural Development

Indus Valley Civilization (3300-1300 BCE): The roots of Hindu civilization stretch back to one of humanity’s earliest urban societies. Archaeological evidence from cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro reveals sophisticated urban planning, advanced drainage systems, and artifacts suggesting early religious practices—including proto-Shiva figures and ritual bathing facilities—that may have influenced later Hindu traditions. Though we cannot decipher their script, these Bronze Age peoples established patterns of spiritual and social organization that would echo through subsequent Indian history.

Vedic Age (1500-500 BCE): The tradition truly began to take recognizable form when Indo-European peoples brought with them a collection of sacred hymns, prayers, and rituals that would become the Vedas—Hinduism’s oldest and most authoritative scriptures. During this foundational period, the development of Sanskrit as a sacred language, the establishment of Vedic ritual traditions, and the emergence of early philosophical concepts laid the groundwork for what would become classical Hinduism.

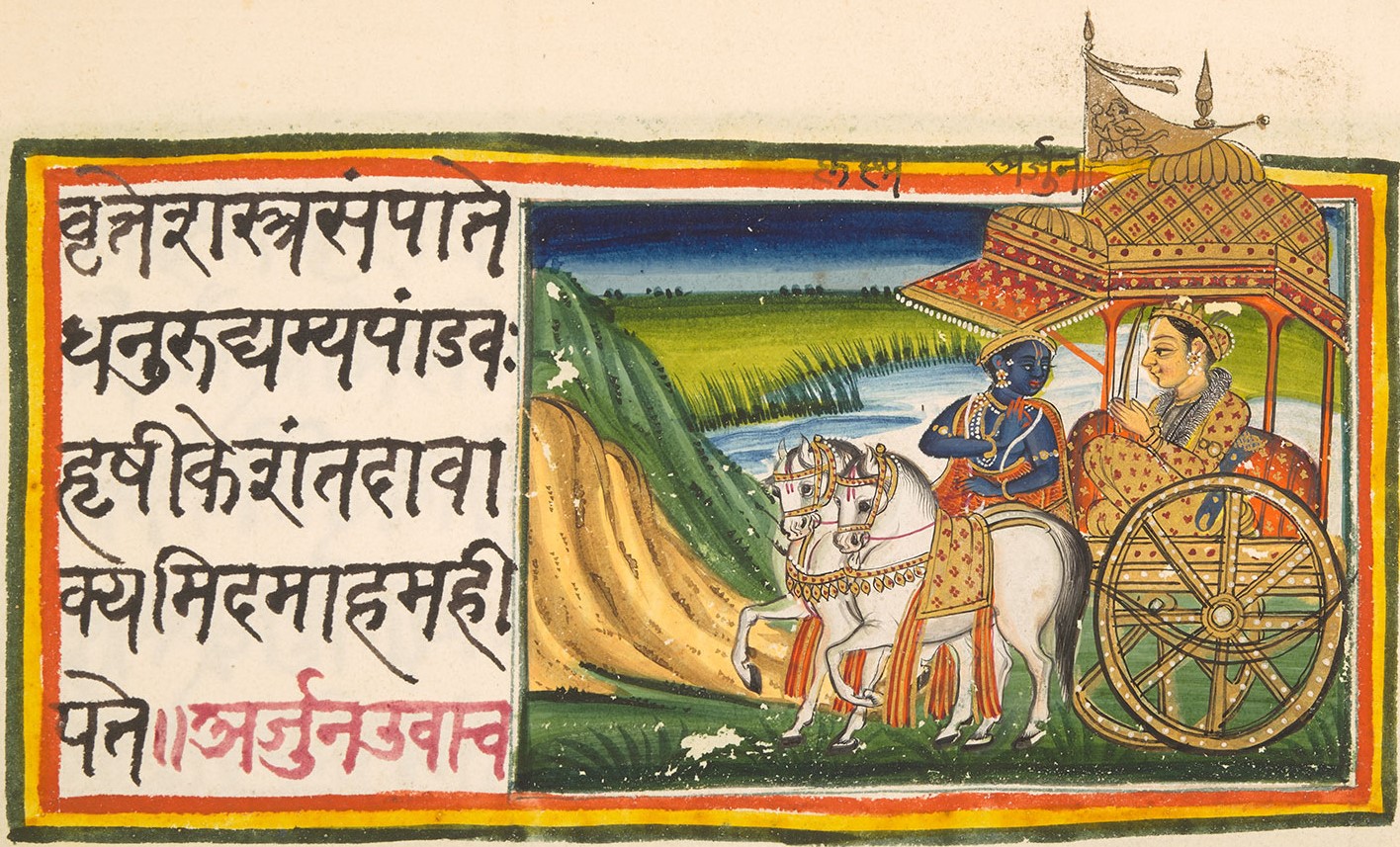

Classical Period (200 BCE-600 CE): Following periods of political fragmentation, the Gupta dynasty reunified much of the subcontinent and presided over a remarkable flowering of Hindu culture. This era witnessed the composition of the great epics—the Mahabharata (including the beloved Bhagavad Gita) and the Ramayana—as well as the systematization of diverse philosophical schools and the construction of the first great Hindu temples. Many elements we associate with modern Hinduism, from devotional practices to temple architecture, crystallized during this golden age.

Mughal Period (1526-1857 CE): Under Muslim rule, Hindu traditions demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability. While some rulers imposed restrictions, others like Akbar promoted religious dialogue and cultural synthesis. This period saw the emergence of devotional movements that emphasized direct spiritual experience over ritual complexity, making Hindu spirituality more accessible to ordinary practitioners.

Modern Era: Following British colonial rule and Indian independence in 1947, Hinduism has grappled with modernization while maintaining traditional wisdom. Contemporary Hindu thought seeks to balance ancient spiritual insights with modern values of equality and social justice, addressing historical practices like the caste system while preserving core philosophical and spiritual teachings.

Core Beliefs and Philosophical Framework

Hindu thought encompasses several fundamental concepts that provide coherent framework despite the tradition’s remarkable diversity:

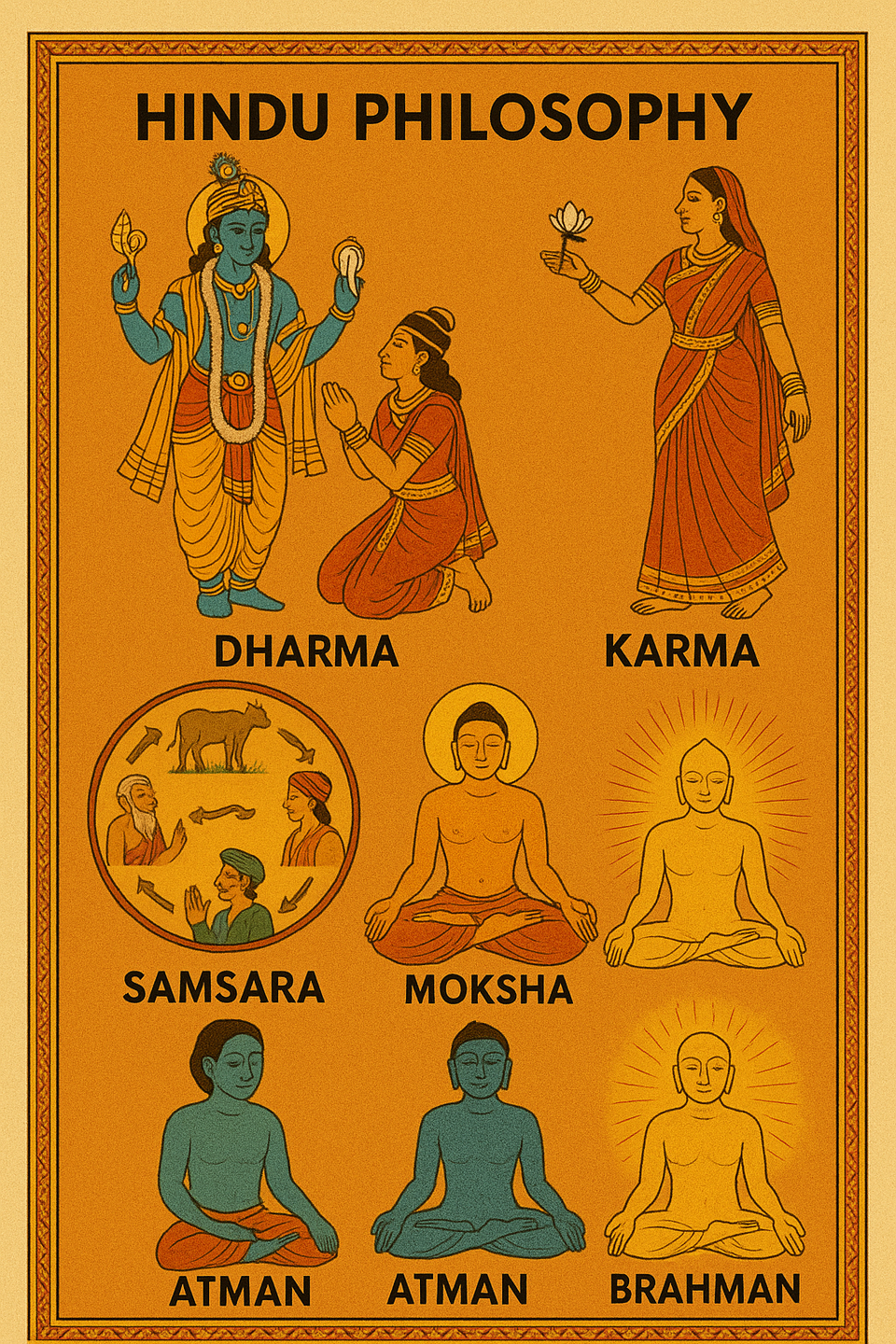

Dharma represents the cosmic law and moral order that governs both individual conduct and universal harmony. For individuals, dharma means fulfilling one’s duties according to their stage of life and social position, but it extends beyond mere social obligation to encompass righteous living that maintains cosmic balance. This concept recognizes that ethical behavior varies with circumstances while maintaining universal principles of truth, non-violence, and compassion.

Karma describes the law of cause and effect governing all intentional actions. Every act—whether physical, mental, or verbal—creates consequences that shape future experiences, both in this life and in subsequent rebirths. This understanding fundamentally links ethical behavior with spiritual progress, suggesting that individuals create their own destinies through conscious choices.

Samsara (Sanskrit “wandering”) refers to the continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth that all souls experience. Unlike linear concepts of existence, Hindu thought envisions consciousness as eternal, taking various forms across countless lifetimes as it learns and evolves. This perspective encourages long-term thinking about spiritual development while explaining apparent inequalities as products of past actions rather than divine favoritism.

Moksha represents the ultimate spiritual goal: liberation from the cycle of samsara through the realization of one’s true nature as identical with Brahman, the universal consciousness underlying all existence. This liberation is not mere escape but rather enlightened recognition of the fundamental unity behind apparent diversity.

Ahimsa, or non-violence, extends beyond physical harm to encompass respect for all living beings. This principle influences dietary practices, lifestyle choices, and broader ethical considerations about humanity’s relationship with the natural world, reflecting Hinduism’s recognition of consciousness in all life forms.

This Khan Academy video provides an overview of these concepts.

Reflection Question

How do these concepts compare with other religious principles we have covered in this textbook? How do they compare with your own religious/spiritual tradition (if you have one)?

Sacred Literature and Intellectual Traditions

Rather than a single authoritative text, Hinduism draws from a vast library of sacred literature spanning thousands of years:

The four Vedas—Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda—contain hymns, prayers, and ritual instructions considered eternal truths revealed to ancient sages during deep meditation. These texts preserve not only religious content but also early developments in astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy.

The Upanishads, philosophical texts exploring the nature of ultimate reality, established sophisticated metaphysical frameworks that influenced both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions. These works introduced concepts like Brahman (universal consciousness) and Atman (individual soul) that remain central to Hindu thought.

The great epics provide narrative frameworks for exploring dharma in complex social situations. The Mahabharata, eight times longer than the Iliad and Odyssey combined, contains the Bhagavad Gita—perhaps Hinduism’s most influential philosophical dialogue, which addresses fundamental questions about duty, action, and spiritual realization in the context of moral conflict.

Art, Architecture, and Cultural Expression

Hindu artistic traditions reflect deep spiritual concepts through visual and performing arts. Temple architecture creates sacred spaces designed to facilitate divine encounter through careful geometric proportions, symbolic sculptural programs, and orientation to cosmic forces. The famous Khajuraho temples demonstrate sophisticated understanding of engineering and aesthetics while expressing Hindu concepts of divine energy and cosmic harmony.

Sculptural traditions portray deities in forms that convey spiritual attributes rather than mere physical likeness. The choice to represent gods with multiple arms, divine implements, and symbolic animals reflects theological concepts about divine powers and cosmic functions rather than limitations of artistic skill.

Hindu artistic traditions influenced other cultures throughout South and Southeast Asia, demonstrating cultural connections that scholarly traditions sometimes overlook. The artistic exchange between Hindu kingdoms and neighboring societies reveals the dynamic, interconnected nature of ancient cultural development.

Hindu Traditions of Science and Mathematics

The Indian subcontinent has contributed some of humanity’s most significant mathematical and scientific innovations, particularly during the Classical period (200 B.C.E. to 600 C.E.) and the centuries that followed. These achievements emerged within Hindu cultural contexts that integrated empirical observation with philosophical and spiritual frameworks.

The Decimal System and the Concept of Zero

Perhaps the most revolutionary contribution of Indian mathematics was the development of the decimal system, including the concept of zero. During and after the Gupta dynasty (320-550 C.E.), Indian mathematicians formalized a place-value system based on powers of ten that fundamentally transformed mathematics worldwide. The mathematician Aryabhata (476-550 C.E.) used sophisticated decimal notation, while Brahmagupta formally defined zero as a number with explicit arithmetic rules in 628 C.E.

The concept of zero represented both a philosophical and practical breakthrough. The Sanskrit word shunya (empty or void) was used for zero and shared linguistic roots with the Buddhist philosophical concept of shunyata (emptiness). While this connection is linguistically clear, the extent to which Buddhist or Hindu philosophy directly influenced the mathematical development of zero remains debated among scholars. What is certain is that Indian culture’s comfort with concepts of emptiness provided a context in which zero could be conceptualized as both a placeholder and a number in its own right—a development that eluded other ancient civilizations. The numerals we use today are actually Hindu-Arabic numerals, having been transmitted from India through the Islamic world to medieval Europe.

Astronomy and Mathematics in Practice

Indian astronomers made sophisticated observations of celestial bodies and developed complex calendrical systems. Building on Vedic traditions, Classical Indian astronomers calculated planetary movements, eclipse predictions, and the length of the solar year with remarkable accuracy. Aryabhata calculated the sidereal year with an error of only about 3 minutes, while later astronomers like Bhaskara II (1114-1185 C.E.) achieved even greater precision. These astronomical calculations were often embedded in religious contexts—the timing of festivals and ritual observances all depended on precise astronomical knowledge.

Indian mathematical knowledge also found practical application in temple architecture. The Shulba Sutras, ancient texts from the late Vedic period (approximately 800-200 B.C.E.), contain geometric formulas for constructing fire altars, demonstrating knowledge equivalent to what would later be called the Pythagorean theorem—predating Pythagoras by several centuries. This integration of mathematical precision with religious purpose illustrates a key feature of Hindu scientific traditions: systematic knowledge served both practical and spiritual ends.

Indian mathematical and astronomical knowledge spread through multiple channels during the Islamic Golden Age. A crucial role was played by the Barmakids—former Buddhist monastery leaders who served as viziers in Baghdad and facilitated the transmission of Indian scientific texts. The Persian scholar Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780-850 C.E.), whose name gives us the word “algorithm,” explicitly acknowledged his debt to Indian mathematical sources in works titled “Book of Indian Computation.” These ideas eventually reached medieval Europe through scholars like Leonardo Fibonacci, fundamentally reshaping European mathematics and contributing to the scientific revolution.

Yet the Indian origins of these contributions are often overlooked in standard historical narratives. Every time we use zero, employ decimal notation, or rely on algorithms, we draw on intellectual traditions developed in ancient and classical India—a legacy that deserves recognition alongside the better-known scientific achievements of ancient Greece, China, and the Islamic world.

Hindu Traditions Beyond India

Hinduism’s adaptability becomes particularly evident in its regional variations outside the Indian subcontinent, where local cultures have created distinctive expressions of Hindu spirituality while maintaining core philosophical principles.

Balinese Hinduism represents perhaps the most striking example of cultural synthesis. Known locally as Agama Hindu Dharma, Balinese practice integrates Hindu concepts with indigenous Austronesian beliefs, creating a unique tradition that emphasizes harmony between humans, nature, and the divine. Balinese temples serve multiple village functions beyond worship, and ritual practices incorporate elaborate artistic expressions—dance, music, and offerings—that reflect local aesthetic sensibilities while honoring Hindu deities. The Balinese concept of Tri Hita Karana (three sources of well-being) demonstrates how Hindu philosophical principles adapt to local cultural priorities emphasizing community harmony and environmental balance.

Southeast Asian Hindu Kingdoms historically developed sophisticated court cultures that blended Hindu cosmology with local political and religious traditions. The great temple complexes of Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Prambanan in Java demonstrate how Hindu architectural principles adapted to local materials, climate, and artistic traditions while maintaining essential spiritual functions. These kingdoms created literary traditions that retold classical Hindu epics through local cultural lenses, making ancient stories relevant to contemporary social circumstances.

Contemporary Diaspora Communities continue this pattern of adaptation, maintaining Hindu spiritual practices while engaging with diverse cultural contexts. From Trinidad’s vibrant Hindu festivals to Fiji’s temple traditions to Western yoga and meditation movements, Hindu concepts continue to evolve through cultural contact while preserving essential insights about consciousness, ethics, and spiritual development.

Reflection Question

Questions about cultural preservation and adaptation affect how Hindu traditions engage with globalization, technological change, and cultural exchange. How do these discussions reflect broader issues about maintaining authentic spiritual traditions while remaining relevant to contemporary spiritual seekers? Can you connect this to your own spiritual tradition if you have one?

The Caste System and Contemporary Challenges

Modern Hinduism faces complex challenges in balancing traditional wisdom with contemporary values. The caste system, historically organizing society into hierarchical groups based on occupation and birth, represents one of Hinduism’s most problematic legacies. While rooted in ancient ideas about spiritual development and social organization, rigid caste distinctions have created profound inequalities that conflict with modern principles of human dignity and equal opportunity.

The caste system divides people into four groups:

- Brahmins: teachers and scholars (the head)

- Kshatriyas: warriors and rulers (the arms)

- Vaishyas: traders and merchants (the legs)

- Shudras: anyone who performs menial labor (the feet).

The dalits, or “untouchables” are the lowest subcaste in the system, which separates people into 25,000 different categories based on their occupations. Throughout most of Indian history, the four main castes were segregated from each other, though many scholars believe that the rigidity of the caste system was not enforced until British Colonial rule.

The Hindu belief in reincarnation meant that a person could go through many lifetimes before achieving the highest caste. Today, the Indian government uses affirmative action to try to end the caste system. Although discrimination is against the law, it remains a problem in Indian society.

Contemporary Hindu movements emphasize the tradition’s core spiritual teachings while challenging social practices that contradict universal values of compassion and justice. Reform efforts focus on recovering Hinduism’s essential insights about the unity of all existence while addressing historical injustices and exclusions.

Hinduism in Global Context

Hindu concepts have profoundly influenced contemporary global spirituality, often in ways that extend far beyond their original cultural contexts. Practices like yoga and meditation, philosophical concepts like karma and dharma, and therapeutic approaches derived from Ayurvedic medicine have become integral to worldwide wellness and spiritual movements.

This global influence reflects Hinduism’s fundamental insight that spiritual truth transcends cultural boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in specific traditions and practices. The challenge lies in maintaining the depth and authenticity of these practices while making them accessible to diverse cultural contexts, as demonstrated by the creative adaptations found in places like Bali.

The global distribution of Hindu communities—from ancient Southeast Asian kingdoms to modern diaspora populations—demonstrates both Hinduism’s cultural adaptability and its capacity to maintain essential spiritual insights across diverse circumstances.

Reflection Question

How do ancient Hindu concepts like dharma, karma, and ahimsa offer relevant guidance for contemporary global challenges such as environmental destruction, social inequality, and cultural conflict? Consider both the potential contributions and limitations of applying traditional spiritual wisdom to modern problems.

Conclusion: Understanding Hindu Achievement

Hinduism’s enduring contribution to human civilization lies not in any single doctrine or practice but in its demonstration that spiritual traditions can maintain essential insights while adapting to changing circumstances. Through millennia of political upheaval, cultural contact, and intellectual development, Hindu traditions have preserved sophisticated understandings of consciousness, ethics, and the relationship between individual and cosmic harmony.

The tradition’s emphasis on diverse paths to truth, its recognition of the sacred in everyday life, and its integration of philosophy with practical wisdom continue to offer valuable resources for contemporary seekers navigating questions of meaning, purpose, and connection in an increasingly complex world. As one of humanity’s oldest continuous spiritual traditions, Hinduism provides both historical perspective on religious development and ongoing insights into the perennial human quest for understanding and transcendence.

Putting It All Together

How does Hinduism’s ability to adapt across cultures while maintaining core beliefs offer lessons for how ancient wisdom traditions can remain relevant in our globalized world? You may want to consider Nina Paley’s film Sita Sings the Blues as you think about this question. The film demonstrates both the creative potential and the pitfalls of cross-cultural adaptation of Hindu traditions.

Resources for Further Study

- Encyclopedia Britannica delivers comprehensive foundational knowledge of Hinduism

- Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies provides cutting-edge academic insights

- Harvard’s free Hindu scripture course unlocks textual traditions

- The British Museum showcases living cultural traditions in India

- The Smithsonian offers American institutional perspective with global reach