18 Exploring Buddhism and Shinto: Spiritual Traditions and Cultural Synthesis

“The Buddha was not interested in theology or cosmology. He didn’t speak on these subjects and in fact would not answer questions on them. His primary concerns were psychological, moral, and highly practical ones.”

— Steve Hagen, founder and head teacher of the Dharma Field Zen Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Introduction: Two Spiritual Paths, One Cultural Landscape

Buddhism and Shinto represent two of the world’s most influential spiritual traditions, each offering distinct approaches to understanding existence, morality, and the sacred. While Buddhism emerged from the Indian subcontinent over 2,500 years ago as a revolutionary approach to human suffering and enlightenment, Shinto developed as Japan’s indigenous religion, rooted in reverence for nature spirits and ancestral wisdom.

The fascinating intersection of these traditions in Japan created one of history’s most successful examples of religious synthesis, shinbutsu shūgō. Rather than competing, Buddhism and Shinto developed a complementary relationship that enabled Japanese people to draw from both traditions simultaneously—turning to Shinto for births, harvests, and connection with ancestral spirits, while embracing Buddhist teachings for funeral rites, philosophical inquiry, and the quest for enlightenment.

Understanding these traditions requires recognizing both their individual characteristics and their remarkable ability to adapt and coexist. Buddhism’s emphasis on personal liberation through ethical conduct and mental discipline found harmony with Shinto’s focus on ritual purity and harmonious relationships with natural and spiritual forces. This synthesis demonstrates how spiritual traditions can maintain their essential characteristics while enriching each other through cultural exchange.

The Origins and Development of Buddhism

Buddhism began in the misty foothills of northeastern India around the 6th century BCE when Siddhartha Gautama achieved enlightenment beneath a Bodhi tree, earning the title “Buddha” or “Awakened One.” This transformative moment sparked one of the world’s oldest continuously practiced spiritual traditions, one that has adapted to diverse cultures while maintaining its core emphasis on alleviating human suffering.

Born Prince Siddhartha Gautama in what is now Nepal, the future Buddha abandoned royal privilege to embark on a spiritual quest after encountering the realities of aging, sickness, and death. He studied with the foremost religious teachers of his time, practicing extreme asceticism and meditation techniques, but this was not enough to achieve liberation from sufferingIn response, the Buddha developed the “Middle Way”—a balanced approach to spiritual practice that avoided extremes. After six years of searching, he achieved enlightenment while meditating under a Bodhi tree, gaining insights into the nature of suffering, impermanence, and the path to liberation.

Following his enlightenment, the Buddha spent 45 years as a wandering teacher, gathering disciples and establishing a monastic community (sangha) that welcomed people from all social backgrounds, which was a radical innovation in India’s rigid caste society. His teaching method emphasized practical guidance over theological speculation, focusing on psychological and ethical transformation rather than metaphysical doctrine.

Reflection Question

Core Buddhist Teachings and Philosophy

Buddhism centers on the Four Noble Truths, which diagnose the human condition and prescribe a path to liberation:

- The First Truth (Dukkha): Life inherently contains suffering, dissatisfaction, and impermanence. This suffering arises not only from obvious sources like illness and death but from the fundamental instability of all conditioned existence.

- The Second Truth (Samudaya): Suffering originates from craving and attachment. Our desires for pleasure, existence, and non-existence create cycles of dissatisfaction that perpetuate suffering.

- The Third Truth (Nirodha): Suffering can be ended through the elimination of craving and attachment. Liberation (nirvana) is possible for all beings through dedicated practice.

- The Fourth Truth (Magga): The Eightfold Path provides practical guidance for achieving liberation through right understanding, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration.

Buddhism also emphasizes the Three Jewels: the Buddha (teacher), Dharma (teachings), and Sangha (community). Additional fundamental concepts include karma (the law of cause and effect), rebirth (continuation of consciousness after death), and the ultimate goal of nirvana (liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth).

Buddhism’s Global Spread and Cultural Adaptation

Buddhism’s expansion beyond India demonstrates remarkable adaptability, as the religion encountered different cultures and philosophical traditions, evolving into distinct branches while maintaining core teachings. This spread occurred along trade routes and through cultural exchange, creating diverse Buddhist traditions across Asia and, eventually, globally.

Major Schools and Regional Developments

Theravada Buddhism (“Way of the Elders”): Predominant in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia, Theravada emphasizes individual liberation through meditation and ethical conduct, closely following early Buddhist texts and monastic discipline. This tradition preserves teachings in the Pali language and emphasizes the arhat ideal—individual enlightenment through personal effort.

Mahayana Buddhism (“Great Vehicle”): Dominant in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, Mahayana developed the bodhisattva ideal—beings who postpone their own final liberation to help all sentient beings achieve enlightenment. This tradition emphasizes universal compassion and includes diverse schools like Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren Buddhism. Mayahana Buddhism is the largest school.

Vajrayana Buddhism (“Diamond Vehicle”): Practiced primarily in Tibet, Mongolia, and some regions of the Himalayas, Vajrayana incorporates tantric practices, elaborate rituals, and esoteric techniques for accelerated spiritual development. This tradition includes extensive use of mantras, mandalas, and visualization practices.

Buddhism’s Journey to East Asia

Buddhism’s transmission to China beginning in the 1st century CE created one of history’s most significant cultural exchanges. Chinese Buddhism developed distinctive characteristics through interaction with Confucian ethics and Daoist philosophy, producing schools like Chan (Zen) Buddhism that emphasized direct experience over textual study.

From China, Buddhism spread to Korea and then to Japan, where it encountered Shinto and created the unique synthesis that characterizes Japanese spirituality. Vietnamese Buddhism developed its own characteristics through interaction with local traditions and Confucian social organization.

Shinto: Japan’s Indigenous Spiritual Tradition

Shinto, literally meaning “the way of the kami,” represents Japan’s indigenous spiritual tradition, developing from prehistoric times as a complex system of beliefs and practices centered on reverence for natural forces, ancestral spirits, and the sacred dimensions of daily life. Unlike many world religions, Shinto has no single founder, canonical scripture, or systematic theology, instead emphasizing ritual practice, communal celebration, and harmonious relationships with spiritual forces.

Core Concepts and Worldview

Shinto’s core concepts reinforce connection to nature and living in harmony with the natural world.

- Kami: Central to Shinto are the kami—spiritual beings or forces that inhabit natural elements like mountains, rivers, trees, and rocks, as well as ancestral spirits and deified humans. Unlike gods in many religious traditions, kami are not omnipotent or morally perfect but represent sacred power and presence in the world. Major kami include Amaterasu (sun goddess), Susanoo (storm god), and countless local and regional spirits.

- Purity and Purification: Shinto places enormous emphasis on ritual cleanliness and purification. Impurity (kegare) can result from death, blood, disease, or moral transgressions and must be removed through ritual washing (misogi), offerings, and ceremonial purification. This concern with purity extends to physical, spiritual, and moral dimensions of life.

- Harmony with Nature: Shinto worldview sees the natural world as inherently sacred, filled with kami that must be respected and honored. Rather than seeking to transcend or control nature, Shinto emphasizes living in harmony with natural forces and cycles. This perspective influences Japanese attitudes toward seasons, agriculture, and environmental stewardship.

- Ancestor Veneration: Shinto maintains strong connections with ancestral spirits, honoring deceased family members and community leaders through regular rituals and offerings. Family altars (kamidana) in homes and elaborate funeral and memorial ceremonies preserve relationships between living and dead.

Ritual Practices and Sacred Spaces

Shinto shrines (jinja) serve as dwelling places for kami and centers for community ritual life. These sacred spaces, marked by distinctive torii gates, provide locations for prayers, offerings, and ceremonies that maintain relationships between human communities and spiritual forces.

Festivals (matsuri) represent the vibrant communal dimension of Shinto practice, featuring processions, music, dance, and food that honor specific kami while strengthening community bonds. These celebrations often coincide with agricultural cycles, seasonal changes, and important community events.

Personal Shinto practices include regular shrine visits for prayers and offerings, participation in life-cycle ceremonies (especially births and marriages), and maintenance of household shrines. The tradition emphasizes gratitude, respect, and proper relationship with kami rather than abstract theological understanding.

The Synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto in Japan

When Buddhism arrived in Japan from Korea in the 6th century CE, it encountered the well-established Shinto tradition. Rather than replacing indigenous beliefs, Buddhism and Shinto developed a remarkable synthesis that enabled Japanese people to practice both traditions simultaneously, creating one of history’s most successful examples of religious coexistence, called shinbutsu shūgō.

Historical Development and Integration

The initial introduction of Buddhism to Japan involved political and cultural negotiations between Japanese rulers and Buddhist monks from Korea and China. Prince Shotoku (574-622 CE) played a crucial role in promoting Buddhist teachings while maintaining respect for Shinto traditions, establishing a pattern of religious pluralism that would characterize Japanese spirituality.

During the Nara (710-794) and Heian (794-1185) periods, Buddhism gained increasing influence among the aristocracy and educated classes while Shinto maintained its importance in rural communities and popular religion. Rather than competing, the traditions began complementing each other in various aspects of Japanese life.

The development of “Dual Shinto” (Ryobu Shinto) created explicit theological connections between Buddhist and Shinto deities, with kami understood as manifestations of Buddhist bodhisattvas and buddhas. This synthesis enabled practitioners to honor both traditions without experiencing religious conflict.

Practical Religious Synthesis

The practical integration of Buddhism and Shinto created a division of religious labor that addressed different aspects of human experience:

Shinto Domains: Birth ceremonies, coming-of-age rituals, marriage celebrations, agricultural festivals, and community celebrations typically involved Shinto practices. These occasions emphasized joy, life force, fertility, and harmonious relationships with natural and ancestral spirits.

Buddhist Domains: Funeral rites, memorial services, philosophical education, and personal spiritual development primarily used Buddhist frameworks. Buddhism’s sophisticated approaches to death, karma, and liberation complemented Shinto’s life-affirming celebrations.

Shared Spaces: Many religious sites incorporated both Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, enabling practitioners to honor both traditions in single locations. Religious festivals often combined elements from both traditions, creating rich ceremonial expressions.

This synthesis enabled Japanese people to approach different life situations with appropriate spiritual resources while maintaining cultural coherence. Most Japanese people practiced both traditions without experiencing contradiction or conflict between them.

Reflection Question

Art, Architecture, and Cultural Expression

Buddhist and Shinto traditions profoundly influenced Japanese artistic development, creating distinctive forms of architecture, sculpture, painting, and decorative arts that reflect both religious values and aesthetic principles. These artistic traditions demonstrate how spiritual beliefs translate into material culture while adapting to local preferences and available materials.

Buddhist Artistic Traditions

Buddhist art in Japan adapted continental Asian models to create distinctively Japanese expressions of Buddhist themes and values. Early Buddhist temples followed Chinese and Korean architectural styles but gradually developed Japanese characteristics that reflected local aesthetic preferences and building techniques.

Buddhist sculpture, particularly statues of buddhas and bodhisattvas, combined spiritual symbolism with artistic excellence. The Great Buddha of Nara, cast in bronze during the 8th century, demonstrates both the technical capabilities of Japanese artisans and the religious devotion that motivated such monumental projects.

Buddhist painting traditions include mandala art, portrait paintings of Buddhist masters, and narrative scrolls depicting Buddhist stories and teachings. These works served both devotional and educational functions, making Buddhist concepts accessible to various audiences while demonstrating sophisticated artistic techniques.

Shinto Architectural and Artistic Forms

Shinto architecture emphasizes simplicity, natural materials, and harmony with surrounding landscapes. Shrine buildings typically use unpainted wood, thatched roofs, and clean geometric lines that reflect Shinto values of purity and natural beauty. The periodic rebuilding of major shrines, exemplified by Ise Shrine’s 20-year renewal cycle, maintains traditional building techniques while symbolizing spiritual renewal.

Torii gates, the distinctive entrance markers to Shinto shrines, create sacred boundaries between ordinary and sacred space. These structures, ranging from simple wooden posts to elaborate vermillion constructions, demonstrate how Shinto marks sacred geography while maintaining architectural elegance.

Shinto artistic objects include mirrors, swords, and jewels that serve as sacred symbols (shintai) housing kami presence. These objects, often hidden from public view, represent spiritual power through material form while maintaining the mysterious character of kami.

Synthesis in Artistic Expression

The integration of Buddhist and Shinto artistic traditions created hybrid forms that reflect Japan’s religious synthesis. Temple-shrine complexes combined both architectural styles, while artistic programs incorporated imagery from both traditions. Garden design, influenced by both Buddhist concepts of contemplation and Shinto reverence for natural beauty, created distinctive Japanese aesthetic approaches that influenced global garden art.

The Chinese-influenced tradition of wen ren (scholar-artists) who combined poetry, painting, and calligraphy found Japanese expression through artists who drew inspiration from both Buddhist philosophy and Shinto nature appreciation.

Cultural Connections

- The Asian Art Museum’s collections of Buddhist and Shinto art

- Traditional Japanese garden design and its spiritual influences

- The preservation of traditional craft techniques in temple and shrine construction

Science, Mathematics, and Technology in Buddhist and Shinto Cultures

The spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road carried more than spiritual teachings—it also facilitated one of history’s great exchanges of scientific and mathematical knowledge. Chinese innovations in astronomy, mathematics, and technology profoundly shaped East Asian civilizations and eventually the entire world. Chinese astronomers were charting celestial movements as early as the Shang Dynasty (1339 BCE), and by 1039 BCE had determined that the sun and moon were spherical. The development of the armillary sphere in the first century BCE—an intricate device for mapping the heavens—demonstrated China’s sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics. Perhaps most famously, the “Four Great Inventions” of China—paper, gunpowder, printing, and the compass—transformed not only East Asian society but eventually revolutionized global civilization.

When Buddhism traveled to Japan, it brought with it Chinese learning and catalyzed distinctive Japanese innovations. During the Edo period (1603-1868), Japanese mathematics (wasan) flourished independently of Western influence. Mathematicians like Seki Takakazu developed algebraic methods and determinants that paralleled—and sometimes preceded—similar European discoveries. What makes wasan particularly fascinating is its connection to spiritual practice: mathematicians created sangaku, ornate wooden tablets displaying geometric puzzles and elegant proofs, which were hung as offerings in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. These mathematical dedications to the kami represent a unique fusion of intellectual achievement and religious devotion.

Japanese metallurgy achieved legendary status through sword-making techniques that remain unmatched in sophistication. Creating a traditional katana involved folding steel thousands of times to produce layered structures that were simultaneously flexible and razor-sharp—a process requiring profound understanding of material properties, heat treatment, and craftsmanship. This same obsessive attention to precision and quality would later characterize Japanese approaches to modern manufacturing and technology.

The Buddhist concept of impermanence (anicca) paradoxically coexists with an intense cultural focus on perfection and longevity, while Shinto’s reverence for kami has inspired a distinctive relationship with technology. Unlike Western cultures that often frame artificial intelligence in terms of “playing God,” many Japanese engineers view creating intelligent machines as a natural extension of their animistic worldview, where spirits can inhabit objects. This spiritual-technological synthesis has made Japan a global leader in robotics while maintaining deep connections to ancient traditions—a perfect example of how Buddhism and Shinto continue to influence even cutting-edge scientific endeavors.

Buddhism in the Western Imagination

Buddhism’s encounter with Western culture represents one of the most significant spiritual and cultural exchanges of modern times. Since the mid-20th century, Buddhism has experienced unprecedented popularity in North America and Europe, though this adoption has often involved selective appropriation rather than comprehensive understanding of Buddhist traditions.

Western interest in Buddhism has often focused on meditation techniques, philosophical concepts, and aesthetic elements while minimizing or ignoring the cultural contexts, institutional structures, and comprehensive worldviews that characterize traditional Buddhist societies. This selective adoption has created “Buddhist-inspired” practices that may differ significantly from historical Buddhist traditions.

Popular Western Buddhism often emphasizes individual spiritual development, stress reduction, and personal happiness rather than traditional Buddhist concerns with liberation from rebirth cycles, extensive ethical training, and community responsibility. While these adaptations may provide genuine benefits, they represent significant departures from traditional Buddhist priorities.

The commercialization of Buddhist symbols, meditation techniques, and aesthetic elements in Western consumer culture has created “Buddhist” products and services that may have little connection to authentic Buddhist practice while potentially trivializing profound spiritual traditions.

Serious Western engagement with Buddhism has also produced genuine scholarly understanding, authentic practice communities, and meaningful cultural exchange. Western practitioners who commit to traditional training, language study, and cultural understanding have contributed to global Buddhist dialogue while adapting practices appropriately to Western contexts.

The dialogue between Buddhism and Western psychology, medicine, and neuroscience has created new areas of research and practical application that benefit both traditions. Scientific studies of meditation, Buddhist approaches to mental health, and contemplative practices have enriched both Western understanding and Buddhist teaching methods.

Reflection Question

Contemporary Practice and Global Influence

Buddhism and Shinto continue evolving in contemporary contexts while maintaining connections to traditional teachings and practices. These traditions face challenges from modernization, globalization, and changing social conditions while demonstrating remarkable adaptability and continued relevance.

Buddhism in the Modern World

Contemporary Buddhism encompasses traditional monastic communities, lay practice groups, engaged Buddhism movements addressing social issues, and innovative teaching methods that use modern technology and communication. Buddhist teachers work to preserve authentic teachings while making them accessible to contemporary practitioners facing modern challenges.

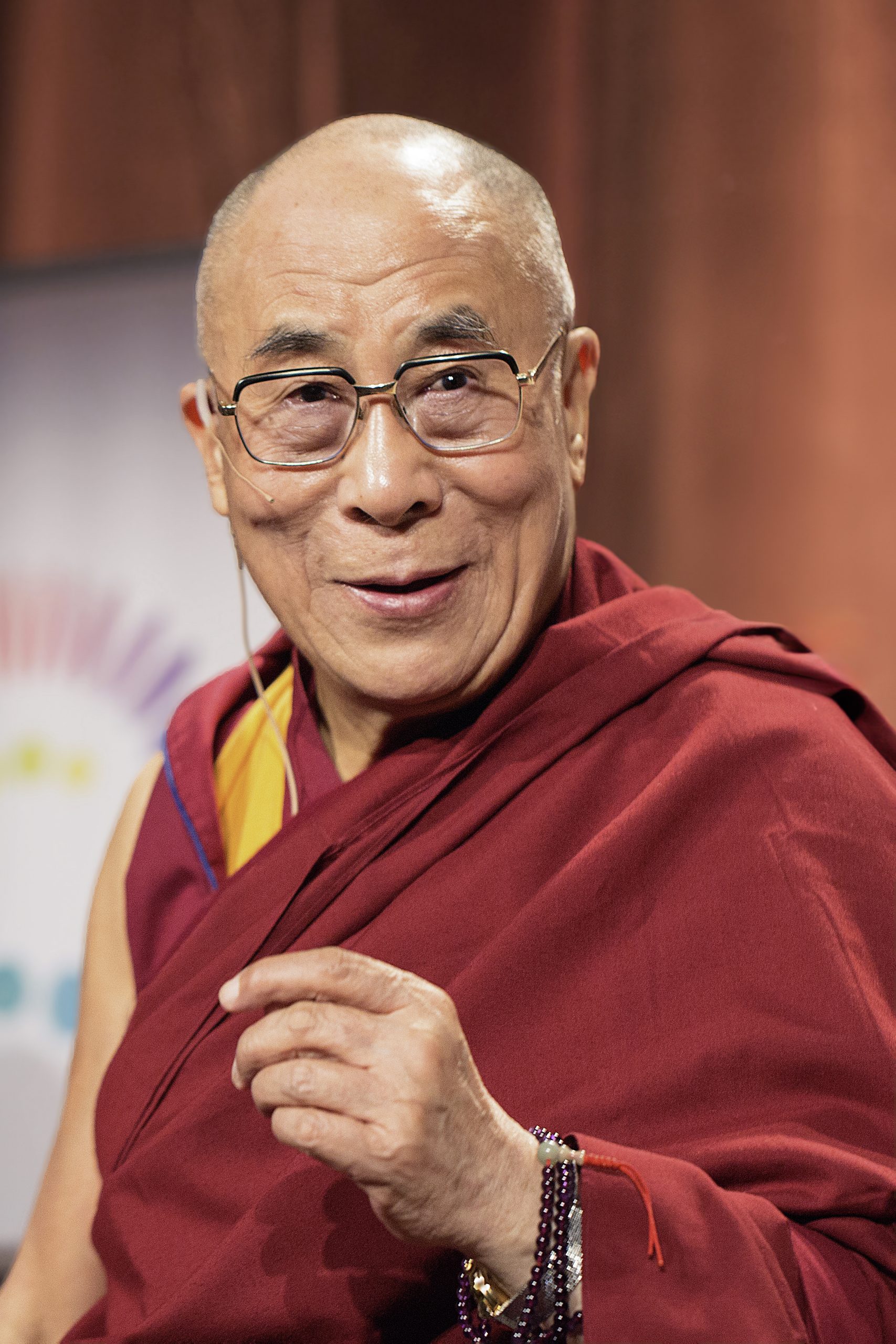

Engaged Buddhism, exemplified by leaders like Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama, applies Buddhist principles to social justice, environmental protection, and conflict resolution. This movement demonstrates how traditional spiritual wisdom can address contemporary global challenges while maintaining Buddhist ethical foundations.

Buddhist meditation and mindfulness practices have influenced Western psychology, education, and healthcare, creating secular applications of traditional techniques while raising questions about the relationship between spiritual practice and therapeutic intervention.

Shinto in Contemporary Japan

Contemporary Shinto maintains its importance in Japanese cultural life through shrine visits, seasonal festivals, and life-cycle ceremonies, though explicit religious belief may be less emphasized than cultural participation. Many Japanese people participate in Shinto practices as expressions of cultural identity and community belonging rather than doctrinal commitment.

Modern challenges for Shinto include urbanization that disrupts traditional community structures, changing family patterns that affect ancestor veneration practices, and questions about the relationship between Shinto and Japanese nationalism following World War II experiences.

Environmental movements in Japan increasingly draw on Shinto concepts of nature reverence and harmony with natural forces, demonstrating how traditional spiritual values can inform contemporary ecological consciousness.

Global Influence and Cultural Exchange

Both Buddhism and Shinto continue influencing global culture through art, philosophy, environmental thinking, and approaches to mental health and spiritual development. Japanese concepts like “forest bathing” (shinrin-yoku) and mindfulness practices derived from Buddhist meditation demonstrate how traditional wisdom adapts to contemporary needs. The films of Hiyao Miyuzaki, including Oscar-winning Spirited Away, introduced younger Western audiences to Shinto concepts.

The global interest in Japanese culture, from martial arts to garden design to minimalist aesthetics, often reflects underlying Buddhist and Shinto values about simplicity, harmony, and mindful attention to present experience.

Conclusion: Wisdom Traditions for a Connected World

Buddhism and Shinto offer profound insights into human nature, spiritual development, and harmonious living that remain relevant for contemporary global challenges. These traditions demonstrate how spiritual wisdom can adapt to different cultural contexts while maintaining essential teachings about compassion, mindfulness, and respectful relationship with the natural world.

The successful synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto in Japan provides a model for how different spiritual traditions can coexist and enrich each other without losing their distinctive characteristics. This religious pluralism offers alternatives to conflict-based approaches to religious difference while demonstrating the creative potential of cultural exchange.

Perhaps most importantly, both traditions emphasize practical wisdom over abstract theorizing, encouraging practitioners to test spiritual teachings through direct experience rather than accepting them as dogma. This empirical approach to spiritual development offers valuable perspectives for contemporary seekers while respecting the depth and sophistication of traditional wisdom.

As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, the Buddhist emphasis on universal compassion and the Shinto focus on harmonious relationships with all forms of life provide essential guidance for building sustainable and peaceful global communities. These traditions remind us that spiritual development and ethical responsibility are inseparable, and that true wisdom manifests through beneficial action in the world.

Understanding Buddhism and Shinto encourages us to approach spiritual traditions with both respect and critical thinking, appreciating their contributions while avoiding superficial appropriation. These ancient wisdom traditions continue evolving while offering timeless insights into the human quest for meaning, peace, and enlightened living.

Putting It All Together