10 Exploring Native North American Cultures: Sovereignty, Resilience, and Living Traditions

“Honor the sacred. Honor the Earth, our Mother. Honor the Elders. Honor all with whom we share the Earth: Four-leggeds, two-leggeds, winged ones, swimmers, crawlers, plant and rock people. Walk in balance and beauty.” — Lakota Elder

Introduction: Understanding Indigenous Diversity and Sovereignty

Native North American cultures represent extraordinary diversity, encompassing hundreds of distinct nations, languages, and cultural traditions that have thrived on this continent for tens of thousands of years. When European colonizers arrived, they encountered sophisticated societies with complex political systems, advanced agricultural practices, rich artistic traditions, and profound spiritual relationships with the natural world.

As Wilma Mankiller, former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, observes: “Though many non-Native Americans have learned very little about us, over time we have had to learn everything about them. We watch their films, read their literature, worship in their churches, and attend their schools. Every third-grade student in the United States is presented with the concept of Europeans discovering America as a ‘New World’ with fertile soil, abundant gifts of nature, and glorious mountains and rivers. Only the most enlightened teachers will explain that this world certainly wasn’t new to the millions of indigenous people who already lived here when Columbus arrived.”

Understanding Native American cultures requires recognizing both their incredible diversity and their shared experiences of colonization, resistance, and cultural persistence. The term “Native American” itself is contested—many Indigenous people prefer to be identified by their specific tribal nations, while others embrace pan-Indigenous identity. This complexity reflects the ongoing vitality of Indigenous cultures that continue evolving while maintaining connections to ancestral traditions. According to the National Museum of the American Indian, “American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native are acceptable and often used interchangeably in the United States; however, Native Peoples often have individual preferences on how they would like to be addressed.”

Reflection Question

Pre-Contact Diversity and Achievements

Before European contact, North America was home to an estimated 10 million people representing hundreds of distinct cultures, languages, and political systems. These societies developed sophisticated adaptations to diverse environments, from Arctic tundra to southwestern deserts, from Pacific coastlines to Great Plains grasslands.

Regional Cultural Areas

Northeast Woodlands: The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy created one of the world’s oldest participatory democracies, with sophisticated concepts of federalism, women’s political power, and environmental stewardship that influenced early American political thought. Algonquian-speaking peoples like the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) developed complex seasonal migration patterns and sustainable resource management practices.

Southeast: The Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations (later called the “Five Civilized Tribes” by Europeans) developed complex agricultural systems, urban centers, and written constitutions. The Cherokee syllabary, created by Sequoyah in the early 19th century, enabled widespread literacy and newspaper publication.

Great Plains: Contrary to popular stereotypes, Plains cultures included both nomadic buffalo hunters and sedentary agricultural peoples. The Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota nations (collectively referred to as Sioux by Europeans) developed sophisticated horse-based cultures, while the Mandan and Hidatsa built permanent earth lodge villages and maintained extensive trade networks.

Southwest: Ancestral Pueblo peoples (formerly called Anasazi) created architectural marvels like Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace, demonstrating advanced engineering and astronomical knowledge. Contemporary Pueblo nations continue these traditions, while the Navajo (Diné) and Apache peoples developed distinct cultural adaptations to southwestern environments.

Pacific Northwest: Coastal peoples like the Tlingit, Haida, and Pacific Northwest Coast Salish developed some of the world’s most complex hunter-gatherer societies, with sophisticated art traditions, potlatch ceremonies, and sustainable salmon fishing practices that supported large permanent settlements.

Intermountain/Columbia Plateau: Idaho’s Nimíipuu (Nez Perce) developed sophisticated horse breeding programs that produced the renowned Appaloosa, while their 1877 resistance under Chief Joseph demonstrated strategic military leadership against forced removal. The region’s Shoshone, Bannock, and Paiute peoples mastered high desert survival through complex seasonal migrations and extensive trade networks that connected Pacific Northwest, Plains, and Southwest communities.

California: California housed the continent’s greatest linguistic diversity, with over 100 distinct languages. Peoples like the Chumash developed ocean-going vessels and complex island societies, while interior groups like the Miwok created sustainable acorn-based economies.

Cultural Connections

Environmental Management and Agriculture

The “pristine wilderness” that Europeans claimed to discover was actually the result of thousands of years of careful Indigenous land management. Native peoples used controlled burning to maintain grasslands and prevent destructive wildfires, practiced sustainable hunting that maintained animal populations, and developed agricultural systems that enriched rather than depleted soil.

Indigenous agriculture contributed fundamental crops to global food systems: maize (corn), beans, squash, potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, and many others. The “Three Sisters” agriculture of corn, beans, and squash provided sustainable nutrition while improving soil fertility through nitrogen fixation and companion planting.

These agricultural innovations supported large populations and complex societies. Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis, housed 10,000-20,000 people at its peak around 1100 CE, making it larger than London at the time. The city featured massive earthen pyramids, sophisticated urban planning, and trade networks extending across the continent.

Reflection Question:

Spiritual Traditions and Worldviews

Native American spiritual traditions encompass extraordinary diversity while sharing common themes that reflect deep relationships with land, community, and the sacred dimensions of existence. These traditions are not historical artifacts but living practices that continue guiding Indigenous communities today.

Common Elements and Diversity

Many Indigenous traditions recognize the sacred nature of all existence, seeing spiritual power in animals, plants, geographical features, and natural phenomena. The concept of the “Great Spirit” or “Great Mystery” appears across many cultures, though understood differently by each tradition. Most emphasize reciprocal relationships between humans and other beings, requiring proper ceremony and ethical behavior to maintain cosmic balance.

However, this diversity cannot be oversimplified. As scholar Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz explains: “For American Indians, spirituality is part of a broader cultural context where religion is not separate from culture. As part of the continuum of culture, an Indigenous nation’s spirituality is a reflection of the circumstances of life connected to specific places over vast expanses of time and in the context of particular worldviews and language.”

These “original instructions” are oriented toward community survival and cultural perpetuation rather than individual salvation or universal applicability. Each tradition emerges from specific landscapes, historical experiences, and cultural contexts that cannot be separated from their spiritual meaning.

Ceremonial Practices and Sacred Knowledge

Native ceremonial practices maintain relationships between human communities and the broader web of existence. Seasonal ceremonies mark agricultural cycles, life transitions, and spiritual renewals. Vision quests, sweat lodge ceremonies, pow-wows, and sacred pipe ceremonies serve different functions in different traditions while sharing emphasis on community connection and spiritual renewal.

Many ceremonies require specialized knowledge passed down through generations of training and practice. This sacred knowledge often includes healing practices, astronomical observations, agricultural timing, and ethical guidance that integrate practical and spiritual wisdom.

Contemporary Challenges: Cultural Appropriation

One significant challenge facing Indigenous communities today is the appropriation of sacred practices by non-Indigenous people. This appropriation often strips ceremonies of their cultural context, commercializes sacred knowledge, and disrespects the communities that have preserved these traditions despite centuries of suppression.

As Dunbar-Ortiz notes, the frame of reference non-Native people bring to Indigenous spiritual practices is “wholly different—and arguably inconsistent with—those of Indian people.” Understanding this difference is crucial for respectful engagement with Indigenous cultures.

Cultural Connections

- Native American spiritual practices and cultural appropriation: Quartz Article

- Indigenous actors on harmful stereotypes of Native Americans from SAG-AFTRA

- Various Native American myths and legends: Native Languages Resources

Languages and Oral Traditions

Native North American languages represent extraordinary diversity, with at least 26 language families encompassing hundreds of distinct languages. This linguistic richness reflects thousands of years of cultural development and adaptation to diverse environments across the continent.

Linguistic Diversity and Current Status

Of the approximately 350 languages spoken in the United States today, about 150 are Indigenous languages. However, this represents a dramatic decline from pre-contact diversity, when over 300 Indigenous languages were spoken. Without active conservation efforts, linguists predict only 20 Indigenous languages may survive to 2050—a catastrophic loss of human cultural diversity.

The Navajo language, with 170,000 speakers, remains the most widely spoken Indigenous language, though even it faces challenges as younger generations increasingly use English as their primary language. Other languages have much smaller speaker populations, with some reduced to a handful of elderly fluent speakers.

According to 2021 date from the U.S. Census Community Survey, Native North American languages were among the most spoken languages in nine states:

- Alaska (Central Yupik, Inupiaq, and Central Siberian Yupik).

- Arizona (Navajo and Western Apache).

- Mississippi (Choctaw).

- Montana (Crow, Siksika, Kalispel-Pend d’Oreille, Cheyenne).

- New Mexico (Navajo, Eastern Keres, Zuni, Tewa, Jemez, Southern Tiwa).

- Oklahoma (Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw).

- South Dakota (Lakota and Dakota).

- Utah (Navajo).

- Wyoming (Arapaho, Shoshoni, Navajo).

Roughly half (47%) of U.S. residents who spoke a Native North American language spoke Navajo.

Writing Systems and Literacy

Most Indigenous cultures traditionally relied on oral transmission for preserving cultural knowledge, stories, and historical information. However, several nations developed writing systems to preserve their languages. The previously mentioned Cherokee syllabary, created by Sequoyah in the early 19th century, enabled widespread Cherokee literacy and the publication of the Cherokee Phoenix, one of the first Indigenous newspapers.

Today, most Indigenous languages use the Roman alphabet for writing, though some preserve traditional syllabaries. Language preservation efforts include immersion schools, digital archives, and community-based programs that connect elders with younger learners.

Cultural Connections

- Lakota Language Consortium: Language Preservation Efforts

- Nimiipuu Language Program (Nez Perce): Video Lessons

- Native language resources and preservation: Native Languages Website

Oral Literature and Cultural Transmission

Indigenous oral traditions encompass creation stories, historical narratives, moral teachings, and practical knowledge passed down through generations. These traditions use sophisticated literary techniques including symbolism, repetition, and performance elements that engage memory and transmit cultural values.

Coyote stories from the Southwest, Raven tales from the Pacific Northwest, and Turtle Island creation narratives from the Northeast represent different regional traditions while sharing common themes about the relationships between humans, animals, and the natural world. These stories serve educational functions, providing guidance for ethical behavior, environmental knowledge, and cultural identity.

The oral tradition remains vital in contemporary Indigenous communities, though it faces challenges from English-language dominance and changing social patterns. Many communities are developing innovative approaches to maintain oral traditions while adapting to contemporary circumstances.

You can watch a member of the Nez Perce tribe in Idaho share their creation story here.

Code Talkers and Military Service

During World Wars I and II, Native American servicemen used their Indigenous languages to create unbreakable military codes. Navajo Code Talkers in the Pacific Theater and other Indigenous code talkers in different theaters of war used their languages’ complexity and limited number of speakers to protect crucial military communications.

This service represents both Indigenous patriotism and the irony that languages targeted for destruction by government boarding schools became crucial for national defense. The Code Talkers’ contributions remained classified for decades, reflecting the complex relationship between Indigenous peoples and the American government.

Arts, Crafts, and Material Culture

Indigenous artistic traditions encompass diverse media, techniques, and cultural meanings that reflect both aesthetic values and spiritual beliefs. From petroglyphs carved into stone thousands of years ago to contemporary Indigenous artists working in modern media, Native American arts demonstrate both cultural continuity and creative innovation.

Traditional Art Forms and Techniques

Indigenous artists worked with materials available in their environments, creating sophisticated techniques for working with clay, wood, stone, metals, textiles, and organic materials. Pueblo pottery traditions from the Southwest demonstrate technical mastery and aesthetic sophistication developed over centuries. Kwakwaka’wakw carvers from the Pacific Northwest created complex ceremonial masks that combine artistic achievement with spiritual function.

Basket making traditions, represented by artists like Dat so la lee (Louisa Keyser) of the Washoe people, achieved extraordinary technical and artistic sophistication. These baskets served practical functions while demonstrating cultural knowledge about plant materials, seasonal harvesting, and design traditions passed down through families.

Beadwork, quillwork, and textile traditions combine artistic expression with cultural identity, with specific patterns and colors often carrying tribal significance. The development of these traditions demonstrates Indigenous innovation and adaptation, particularly as artists incorporated new materials like glass beads obtained through trade.

Contemporary Indigenous Arts

Contemporary Native American artists work in all media, from traditional forms to digital art, film, and installation work. These artists often address themes of cultural identity, historical trauma, environmental justice, and Indigenous resilience while maintaining connections to traditional artistic values and techniques.

The Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, and other venues provide platforms for Indigenous artists to share their work while maintaining cultural authenticity and economic independence. These events demonstrate the vitality of contemporary Indigenous arts and their connections to traditional cultural practices.

Colonization, Resistance, and Survival

The European colonization of North America represents one of history’s most dramatic cultural disruptions, involving disease epidemics, warfare, forced displacement, and systematic efforts to destroy Indigenous cultures. However, the history of colonization is also a history of Indigenous resistance, adaptation, and cultural survival against overwhelming odds.

Disease, Warfare, and Population Decline

Epidemic diseases introduced by Europeans caused catastrophic population decline among Indigenous peoples, with mortality rates reaching 90% in some areas. Smallpox, measles, typhus, and other diseases spread rapidly through populations with no previous exposure, devastating communities and disrupting cultural transmission.

This demographic catastrophe facilitated European colonization by reducing Indigenous populations’ ability to resist territorial encroachment. However, disease impact varied significantly across regions and communities, with some groups maintaining larger populations and political autonomy longer than others.

Military conflicts between Indigenous nations and European colonizers involved complex alliances and shifting political relationships. Indigenous nations used diplomatic and military strategies to maintain autonomy, often playing European powers against each other to preserve their interests.

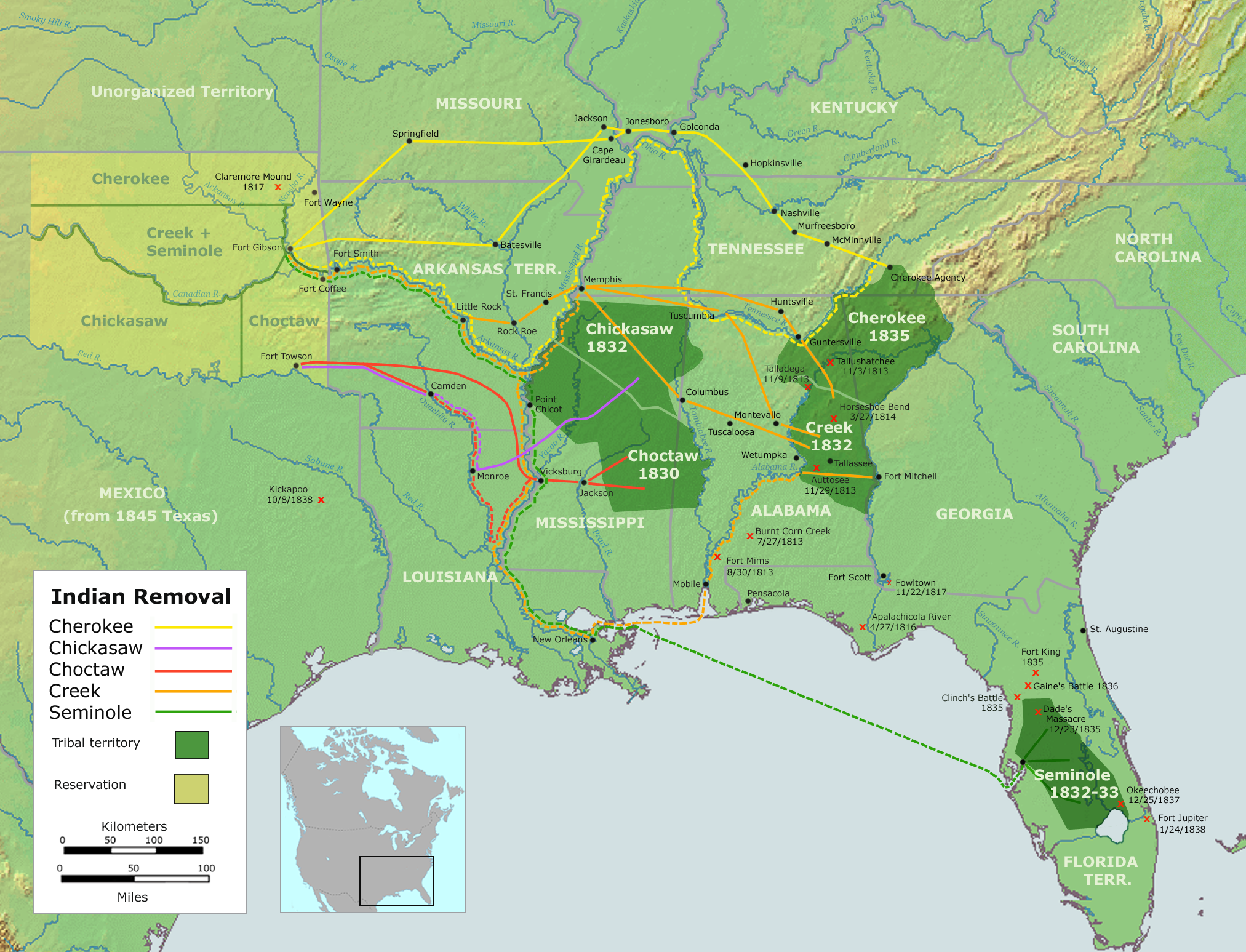

Forced Removal and the Trail of Tears

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 formalized the U.S. government’s policy of forcing Indigenous nations from their ancestral lands to territories west of the Mississippi River. This policy culminated in events like the Cherokee Trail of Tears (1838-1839), when federal troops forced approximately 16,000 Cherokee people to march over 1,000 miles to “Indian Territory” in present-day Oklahoma.

The Cherokee removal exemplifies the broader pattern of forced displacement that affected dozens of Indigenous nations. Despite legal victories like Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which recognized Cherokee sovereignty, President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the Supreme Court decision, stating “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.”

An estimated 4,000 Cherokee people died during the removal, earning the name “Trail of Tears.” Similar forced removals affected other Southeastern nations (Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole) and later extended to Plains and Western tribes. Private John Burnett, who participated in Cherokee removal, later wrote: “I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades… I witnessed the execution of the most brutal order in the History of American Warfare.”

Boarding Schools and Cultural Suppression

Children learning a song, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Photograph by F. Johnston, courtesy of the Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, JO-01-04

Beginning in the late 19th century, the U.S. government implemented a boarding school system designed to “kill the Indian, save the Man.” Children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, forbidden to speak their languages, practice their religions, or maintain cultural connections.

The Carlisle Industrial School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879, served as the model for over 350 boarding schools across the country. These institutions used military-style discipline, manual labor, and Christian indoctrination to eliminate Indigenous cultural identity and prepare students for assimilation into Euro-American society. The boarding school system inflicted severe trauma on multiple generations of Indigenous families, disrupting cultural transmission and creating lasting psychological wounds. However, many students also found ways to maintain cultural connections and used their education to advocate for Indigenous rights.

Indigenous Resistance and Adaptation

Throughout the colonial period and beyond, Indigenous peoples demonstrated remarkable resilience in maintaining cultural traditions while adapting to new circumstances. Leaders like Tecumseh built pan-Indigenous alliances to resist American expansion, while others like Cherokee leader John Ross used legal and diplomatic strategies to protect tribal sovereignty.

The Ghost Dance movement of the late 19th century represented a spiritual response to cultural crisis, offering hope for cultural renewal and the return of traditional ways of life. Although suppressed by the U.S. military, culminating in the Wounded Knee Massacre (1890), the movement demonstrated Indigenous spiritual resilience and resistance to cultural destruction.

Women leaders like Sarah Winnemucca (Northern Paiute) and Susette La Flesche (Omaha) became advocates for Indigenous rights, using their education and language skills to challenge government policies and educate non-Indigenous audiences about Indigenous experiences.

Modern Indigenous Movements and Sovereignty

Contemporary Indigenous movements focus on asserting tribal sovereignty, protecting cultural traditions, and addressing ongoing challenges including poverty, environmental threats, and cultural preservation. These movements draw on both traditional governance concepts and modern political strategies to protect Indigenous rights and promote cultural revitalization.

Red Power and the American Indian Movement

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the emergence of militant Indigenous activism that challenged government policies and demanded recognition of treaty rights. The American Indian Movement (AIM) organized protests including the occupation of Alcatraz Island (1969-1971) and the Trail of Broken Treaties march to Washington, D.C. (1972).

The 71-day standoff at Wounded Knee (1973) brought international attention to Indigenous issues while highlighting tensions between traditional and modern approaches to Indigenous politics. These movements achieved significant policy changes, including the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975) and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978).

Tribal Sovereignty and Self-Determination

Contemporary Indigenous nations exercise varying degrees of sovereignty over their territories, maintaining their own governments, legal systems, and economic development strategies. Gaming revenues have provided some tribes with economic resources for cultural preservation, education, and healthcare, though this development remains controversial within Indigenous communities.

The doctrine of tribal sovereignty recognizes Indigenous nations as “domestic dependent nations” with inherent rights to self-governance. However, this sovereignty exists within complex legal and political relationships with federal and state governments that continue evolving through legislation, court decisions, and political negotiations.

Environmental Justice and Cultural Protection

Many contemporary Indigenous movements focus on environmental protection, recognizing the connection between land preservation and cultural survival. The Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock (2016-2017) brought international attention to Indigenous environmental activism and the relationship between energy development and tribal sovereignty.

Indigenous communities often face disproportionate environmental impacts from extractive industries, nuclear waste storage, and climate change. Traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous environmental ethics provide alternative approaches to environmental management that emphasize sustainability and intergenerational responsibility.

Contemporary Indigenous Life and Cultural Revitalization

Indigenous communities today are experiencing a cultural renaissance while navigating ongoing challenges including poverty, health disparities, and the need to preserve traditional knowledge. Young Indigenous people are finding innovative ways to blend ancestral wisdom with contemporary life, using digital technology and social media to revitalize languages, share cultural practices, and raise awareness about Indigenous issues.

Educational initiatives like tribal colleges and immersion schools combine traditional knowledge with modern academic skills, while language revitalization programs work urgently to preserve Indigenous languages before they disappear. Economic development efforts focus on cultural tourism, sustainable agriculture, and traditional arts while balancing market opportunities with cultural integrity and avoiding exploitation of sacred traditions.

Indigenous contributions to global civilization extend far beyond commonly known agricultural innovations to include political concepts that influenced American democracy, environmental management practices now essential for addressing climate change, and medical knowledge that provided numerous pharmaceuticals to modern medicine. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s political structure influenced early American federalism, while Indigenous concepts of consensus decision-making, gender equality, and environmental responsibility offer valuable alternatives to contemporary governance challenges.

Despite facing significant challenges including political underrepresentation and environmental threats to traditional territories, Indigenous communities demonstrate remarkable resilience through strong family networks, cultural preservation efforts, and growing political influence that continues to shape discussions about sustainability, governance, and social justice.

Conclusion: Honoring Indigenous Resilience and Ongoing Sovereignty

Native North American cultures demonstrate extraordinary resilience, having survived genocide and forced assimilation while maintaining distinct identities and contributing to global civilization. Contemporary Indigenous communities are dynamic societies that continue evolving while honoring ancestral traditions, with young Indigenous people creating innovative expressions of cultural identity that address modern challenges.

Indigenous concepts of sustainability, community responsibility, and spiritual relationship with the natural world provide essential wisdom for contemporary environmental and social crises. Their experiences demonstrate the human capacity for cultural resilience and the importance of maintaining diverse approaches to organizing societies.

As we study Indigenous cultures, we must remember these are living traditions maintained by contemporary communities with ongoing needs, rights, and aspirations. Learning about Indigenous cultures requires approaching them with respect and commitment to supporting Indigenous peoples’ efforts to preserve their traditions while building prosperous futures for their communities.

Putting It All Together

After exploring Native North American cultures, how do you understand the relationship between historical trauma and cultural resilience? What responsibilities do non-Indigenous people have for supporting Indigenous sovereignty and cultural revitalization efforts?

Resources for Further Study:

- National Museum of the American Indian – Comprehensive resources on Indigenous cultures and contemporary issues

- NK360° Educational Resources – Modern Indigenous experiences and cultural education

- Native Languages of the Americas – Language preservation and cultural resources

- Tribal nation websites (linked in the introduction) – Direct sources for contemporary Indigenous perspectives

- Local Indigenous communities and cultural centers – Opportunities for respectful learning and engagement