4 Exploring Maya Culture: Masters of Time, Science, and Sacred Knowledge

“The Maya today—we are the direct descendants of our ancient culture made up of expert builders, excellent astronomers, precise calendar keepers, and experienced artists. We give continuity to our traditions, our ways of thinking and our language, and we are worthy heirs of our origins. Weyano’one—we are here.” — José Huchim Herrera, Yucatec Maya Archaeologist and Architect

Introduction: A Living Civilization

The Maya civilization represents one of humanity’s most sophisticated achievements in astronomy, mathematics, architecture, and written communication. Far from being a “lost” civilization, Maya culture continues to thrive today across Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador, where millions of Maya people maintain their languages, agricultural practices, and spiritual traditions while adapting to contemporary realities.

When we study Maya culture, we encounter a civilization that developed concepts like mathematical zero, created incredibly accurate calendars, built monumental architecture aligned with celestial events, and maintained detailed written records spanning over a millennium. Perhaps most remarkably, Maya communities have preserved essential elements of their culture through centuries of change, offering us insights into both ancient achievements and contemporary resilience.

Cultural Connection

Historical Periods and Development

Maya Chronology

- Archaic (before 2000 BCE): foraging societies

- Preclassic Period (2000 BCE – 250 CE): Agricultural development, permanent settlements, early temple construction

- Classic Period (250 – 900 CE): Golden Age of architecture, astronomy, mathematics, and writing

- Postclassic Period (950 – 1539 CE): Political transformation, continued cultural innovation

- Colonial Period (1511 – 1821 CE): Spanish contact, resistance, and cultural adaptation

- Contemporary Period (1821 – present): Modern nation-state integration while maintaining cultural identity

Understanding Maya history requires recognizing that the Maya were never a single, unified empire but rather a collection of city-states sharing language, religious beliefs, and cultural practices. This decentralized structure enabled remarkable cultural continuity even when individual cities rose and fell.

The Preclassic Foundation (2000 BCE – 250 CE)

During the early Preclassic period, Maya communities developed sophisticated agricultural techniques centered on maize cultivation, along with cacao, fruits, and other crops. These agricultural innovations supported population growth and enabled the development of permanent settlements. By the late Preclassic period, communities were constructing temples and public buildings that demonstrated both architectural sophistication and complex social organization.

The emergence of patrilineal leadership structures during this period established political patterns that would continue throughout Maya history, though these were often more flexible and adaptable than European monarchical systems.

The Classic Period Flowering (250 – 900 CE)

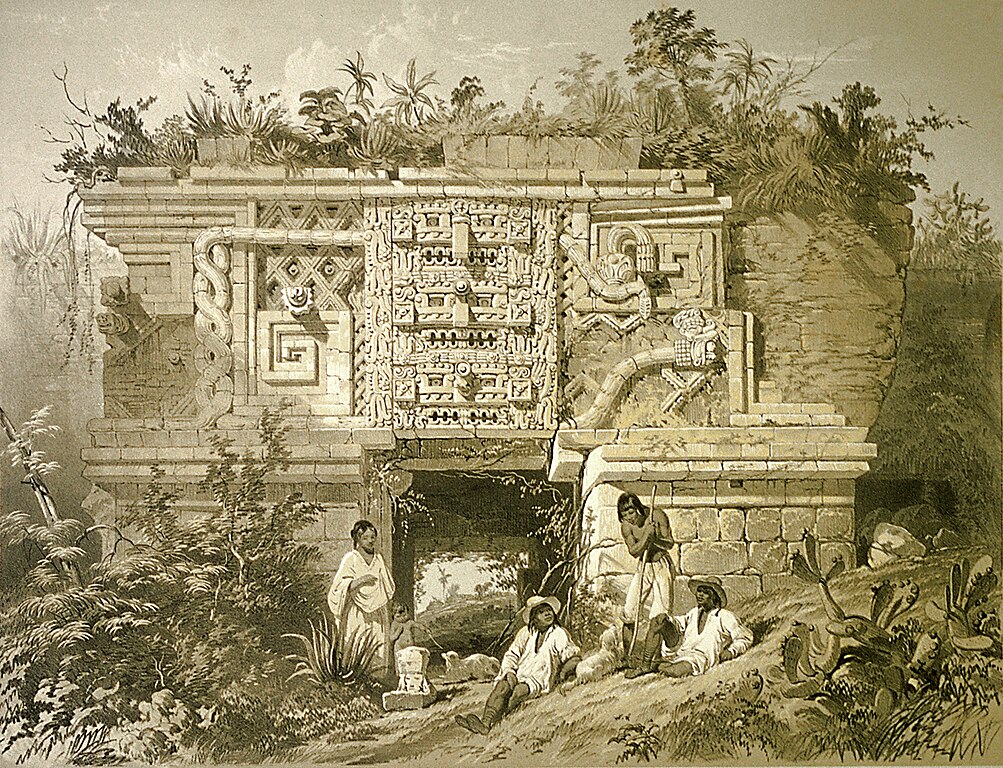

The Classic period witnessed extraordinary Maya achievements across multiple fields. More than 40 major cities housed populations ranging from 5,000 to 50,000 people, creating urban centers that rivaled contemporary European cities in size and sophistication. These cities featured monumental architecture, complex water management systems, and urban planning that integrated astronomical observations with practical needs.

Despite shared cultural elements, Maya city-states maintained political independence, engaging in alliances, trade relationships, and occasional conflicts that created a dynamic political landscape similar to ancient Greece or Renaissance Italy.

Postclassic Adaptation and Spanish Contact (950 – 1539 CE)

The transition to the Postclassic period involved significant political and demographic changes, including the abandonment of some major cities. However, this wasn’t a “collapse” but rather a transformation that saw Maya communities adapting to new challenges while maintaining core cultural practices.

Spanish contact beginning in 1511 initiated dramatic changes, but Maya communities demonstrated remarkable resilience, preserving essential cultural elements while adapting to colonial pressures. The final independent Maya city didn’t fall until 1697, demonstrating sustained resistance and cultural autonomy. To learn more about the Maya and their homelands, explore this interactive map of the Maya world from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Reflection Question

Religious Beliefs and Cosmology

Maya religion centered on maintaining harmony between the human world and the complex cosmos inhabited by over 250 deities. These gods were known by different names across regions but shared fundamental characteristics and roles in maintaining cosmic balance.

This video shows the descent of the serpent god Kukulkan on the spring and winter solstices. The Temple of Kukulkan in the Chichen Itza complex in the Yucatan, Mexico, is one of the UNESCO Seven Wonders of the Modern World. This temple displays the Maya’s sophisticated understanding of mathematics and astronomy.

The Maya Pantheon and Sacred Narratives

Maya deities governed natural forces, agricultural cycles, and human activities. The complexity of the pantheon reflected the Maya understanding that divine forces operated at multiple levels—from cosmic creation to daily agricultural work. Gods could appear in different forms and aspects, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the forces they represented.

Cultural Connection

Creation Story: The Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’ Maya, contains one of the world’s most sophisticated creation narratives. Unlike linear creation stories, it describes multiple creation attempts, reflecting Maya cyclical understanding of time and cosmic renewal.

Learn more about the Maya creation story: Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

The Sacred Ball Game

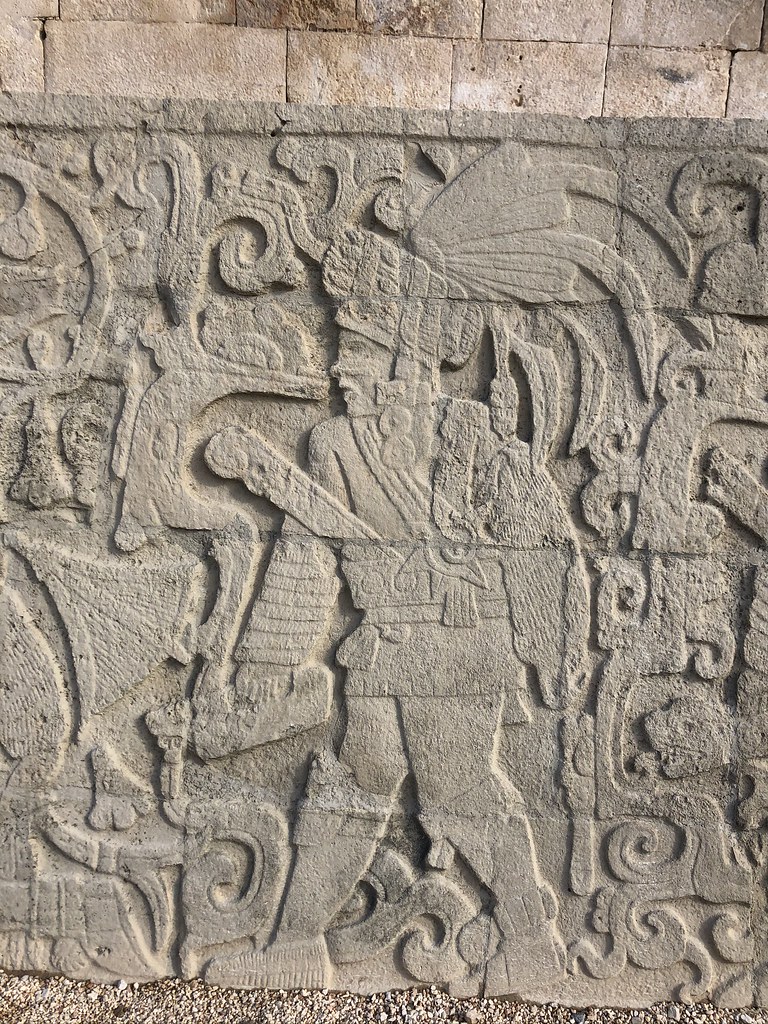

The Maya ball game served crucial religious and social functions throughout Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence from ball courts, frescoes, and burial sites provides insights into this complex ritual activity, though exact rules remain debated among scholars.

The game involved propelling an 8-pound rubber ball through elevated stone hoops using hips, elbows, and knees—no hands or feet allowed. The Popol Vuh describes a cosmic ball game between the Hero Twins and the Lords of Death in Xibalba (the underworld), linking earthly games to cosmic battles between life and death forces.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, evidence suggests that outcomes varied—sometimes winners were honored, sometimes losers were sacrificed, depending on the specific ritual context and regional practices. The game represented cosmic struggle and renewal rather than simple competition. For more information about the ball game, read this short article. This brief video from the Xcaret park shows a modern recreation of what the ball game might have looked like.

Reflection Question

Maya Writing and Literature

The Maya developed the only fully functional writing system in pre-Columbian America, creating a complex script that combined logographic and syllabic elements similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs but independently invented. This writing system enabled the preservation of historical records, astronomical observations, religious texts, and literary works spanning over a millennium.

The Hieroglyphic Script

Maya hieroglyphs could represent whole words (logograms) or syllable sounds (syllabograms), allowing scribes to write their language with remarkable precision and flexibility. This system enabled the recording of exact dates, specific historical events, individual names, and complex philosophical concepts.

Maya scribes held high social status, often coming from noble families or serving in royal courts. Their training required mastering hundreds of symbols and their combinations, along with astronomy, mathematics, and religious knowledge necessary for creating accurate calendrical and astronomical texts.

The Destruction and Survival of Maya Books

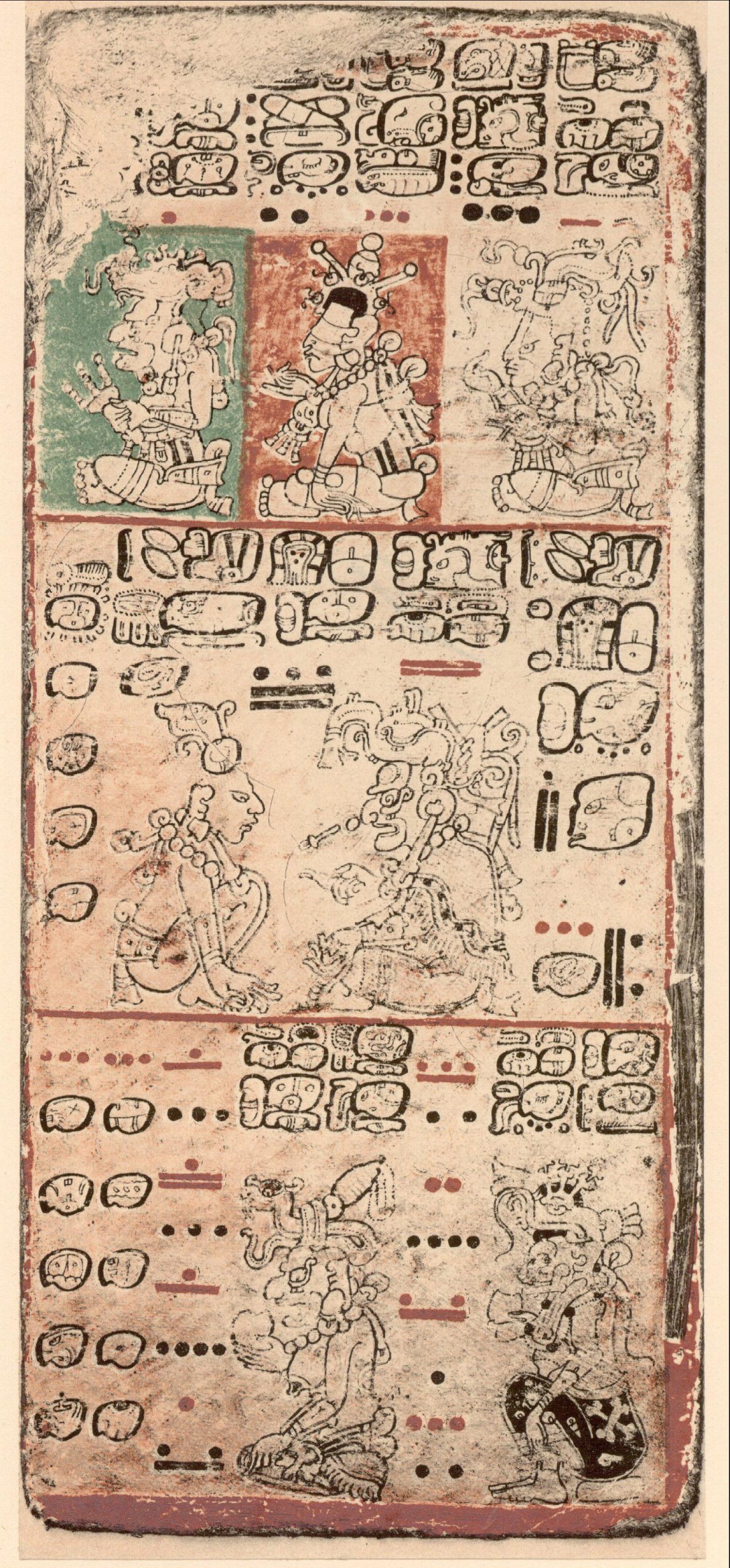

Maya books, called codices, were created from bark paper and contained astronomical tables, ritual calendars, mathematical calculations, and religious ceremonies. Thousands of these books existed throughout the Maya region, representing one of the world’s great literary traditions.

In 1562, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered the burning of Maya books in an auto-da-fé at Maní, Yucatan, describing the event: “We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all.” This cultural destruction eliminated most Maya written literature, representing one of history’s great losses of human knowledge.

Only four Maya codices survive today: the Dresden, Paris, Madrid, and possibly authentic Grolier codices. These precious documents preserve fragments of Maya scientific and religious knowledge, demonstrating the sophistication of Maya intellectual traditions. The Dresden Codex contains detailed astronomical tables and eclipse prediction charts that demonstrate Maya mathematical and observational sophistication. These calculations remain accurate today, testifying to Maya scientific achievements.

Mathematics and Astronomy

Maya mathematics and astronomy achieved remarkable sophistication, enabling precise calendar keeping, architectural planning, and prediction of celestial events. These achievements emerged from practical needs—agricultural timing, religious ceremonies, and architectural orientation—but developed into abstract mathematical concepts that paralleled developments in other world civilizations.

Mathematical Innovation

The Maya developed a vigesimal (base-20) mathematical system that included one of humanity’s few independent inventions of the concept of zero. This mathematical sophistication enabled complex calculations necessary for their astronomical and calendrical work.

Maya mathematicians could perform calculations involving large numbers and developed positional notation that enabled efficient recording of mathematical operations. Their mathematical concepts supported both practical applications (construction, trade, taxation) and abstract astronomical calculations spanning thousands of years.

The video below illustrates how Maya mathematicians performed complex calculations using their vigesimal system.

Astronomical Achievements

Maya astronomers made detailed observations of planetary movements, lunar cycles, and stellar positions that enabled remarkably accurate calendar keeping and prediction of celestial events. They tracked Venus cycles with extraordinary precision, predicting its appearances as morning and evening star over centuries.

Maya architectural achievements demonstrate the integration of astronomical knowledge with religious and social needs. Buildings were oriented to capture specific celestial events—solstices, equinoxes, and planetary alignments—creating structures that functioned simultaneously as temples, observatories, and calendrical markers.

Cultural Connection

The Maya Calendar System

The Maya calendar system represents one of humanity’s most sophisticated achievements in timekeeping, integrating multiple cycles that tracked celestial movements, agricultural seasons, and religious ceremonies with remarkable accuracy. Understanding this system provides insights into Maya science, religion, and worldview.

The Haab Calendar (Solar Year)

The Haab calendar tracked the solar year with 365 days, divided into 18 months of 20 days each, plus a final period of 5 days called Wayeb. This calendar governed agricultural activities and seasonal ceremonies.

Maya farmers continue using the Haab calendar today, conducting offerings and ceremonies (Sac Ha’, Cha’a Chac, and Wajikol) that align agricultural work with cosmic cycles. These ceremonies demonstrate the calendar’s practical importance in maintaining harmony between human activities and natural rhythms.

The Tzolk’in Calendar (Sacred Count)

The Tzolk’in combined 20 named days with 13 numbers, creating a 260-day cycle used for religious ceremonies, divination, and personal identity. Each person received a calendar name based on their birth date in this cycle.

The 260-day period corresponds to human gestation, nine lunar cycles, and the agricultural cycle of corn, linking personal identity with cosmic and natural rhythms. Contemporary Maya communities continue using the Tzolk’in for ceremonial purposes and personal guidance.

The Calendar Round

The Calendar Round combined Haab and Tzolk’in calendars, creating a 52-year cycle (18,980 days) before date combinations repeated. This cycle marked major life transitions, as reaching 52 years signified attaining elder wisdom in Maya society.

Calendar Round dates could uniquely identify any day within a 52-year period, sufficient for most historical and personal record-keeping needs in Maya communities.

The Long Count

For longer historical periods, the Maya developed the Long Count calendar, which tracked days from a mythical creation date (August 11, 3114 BCE in our calendar). This system enabled dating events across millennia and linked historical events to cosmic cycles.

The Long Count measures time in cycles of increasing magnitude: days (k’in), 20-day periods (winal), 360-day years (tun), 20-year periods (katun), and 400-year periods (baktun). A complete cycle of 13 baktuns equals approximately 5,125 years.

Reflection Question

Contemporary Maya Culture

Understanding historical Maya achievements requires recognizing that Maya culture continues evolving today. Contemporary Maya communities maintain languages, agricultural practices, religious traditions, and worldviews that connect directly to ancient traditions while adapting to modern circumstances.

Modern Maya communities demonstrate remarkable cultural resilience. Traditional astronomical knowledge continues to guide agricultural cycles, while ancient calendar systems maintain relevance for ceremonial and personal purposes. Day Keepers (calendar specialists) preserve and transmit calendrical knowledge across generations.

Contemporary Maya artists, writers, and intellectuals contribute to global culture while maintaining distinctive Maya perspectives. This cultural vitality challenges simplistic narratives about “lost” civilizations and demonstrates the ongoing relevance of indigenous knowledge systems.

Cultural Connection

Challenges and Achievements

Contemporary Maya communities face challenges including economic marginalization, land rights disputes, and pressure to abandon traditional practices. However, they also achieve remarkable successes in education, political representation, and cultural preservation. Maya scholars, archaeologists, and community leaders increasingly control research about their own cultures, ensuring that Maya voices shape understanding of both historical achievements and contemporary realities.

Maya culture demonstrates how societies can maintain cultural coherence while adapting to changing circumstances. Their emphasis on cyclical time, community responsibility, and harmony with natural cycles offers alternative perspectives on progress and development that resonate with contemporary environmental and social concerns.

The Maya understanding of time as both linear and cyclical—enabling both historical record-keeping and ritual renewal—provides models for balancing innovation with tradition that remain relevant today.

Reflection Question

Conclusion: Understanding Maya Legacy

Maya civilization represents one of humanity’s great achievements in science, art, literature, and social organization. Their innovations in mathematics, astronomy, writing, and architecture paralleled and sometimes exceeded contemporary developments elsewhere in the world, while their cultural continuity demonstrates remarkable adaptability and resilience.

Perhaps most importantly, Maya culture challenges us to think beyond linear narratives of progress and decline. The continued vitality of Maya communities today demonstrates that cultural achievement involves not just creating innovations but maintaining and adapting traditions across generations of change.

Resources for Further Study

- Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian – Maya

- The Mesoamerica Center

- Mesoamerican Research Center

Video lecture from Nikki Gorrell, a Maya expert at the College of Western Idaho

Final Reflection Question