9 Exploring Norse Culture: Raiders, Explorers, and Storytellers

“The Norse myths are the myths of a chilly place, with long, long winter nights and endless summer days, myths of a people who did not entirely trust or even like their gods, although they respected and feared them.”— Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology

Introduction: Understanding the Norse Legacy

When we think of the Norse, many of us immediately picture fierce Viking warriors with horned helmets (though historically inaccurate!) raiding coastal villages. While this image captures one dramatic aspect of Norse culture, it represents only a small part of a rich and complex civilization that profoundly influenced European history, literature, and culture. The Norse were sophisticated seafarers, skilled craftspeople, innovative storytellers, and explorers who reached North America centuries before Columbus.

The Norse legacy extends far beyond popular culture representations. From J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth to Marvel’s cinematic universe, Norse mythology continues to captivate modern audiences. But to truly understand this influence, we need to explore the historical reality behind the myths and examine how Norse culture developed in the harsh but beautiful landscapes of Scandinavia.

Historical Context and Timeline

Key Periods in Norse History

- Pre-Viking Era (before 793 CE): Agricultural settlements, early trade networks, development of distinctive Scandinavian culture

- Viking Age (793-1066 CE): Period of expansion, raids, exploration, and settlement

- Christianization (1000-1200 CE): Gradual conversion to Christianity, preservation of myths in literary form

The term “Norse” likely derives from “Norseman,” meaning “Northmen,” describing the peoples of northern Scandinavia (present-day Norway, Sweden, and Denmark). During the Viking Age (793-1066 CE), these communities developed one of medieval Europe’s most dynamic cultures, characterized by remarkable mobility, technological innovation, and cultural adaptability.

It’s crucial to understand that not all Norse people were Vikings. The term “Viking” specifically referred to those who participated in overseas raids and expeditions. The majority of Norse society consisted of farmers, craftspeople, traders, and fishermen who lived in settled communities. However, the Viking expeditions were deeply embedded in Norse social structure and values, serving as a way for younger sons to gain wealth and status in a society where land inheritance typically went to the eldest male heir.

Norse Religion and Cosmology

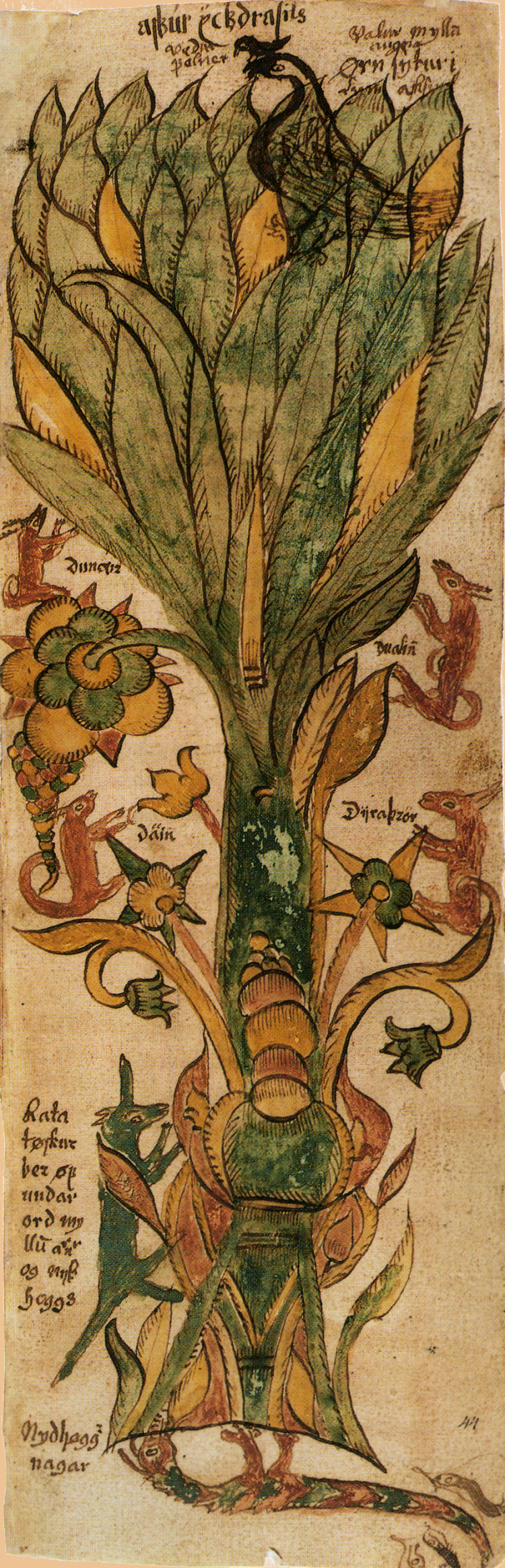

Norse religious beliefs reflected the challenging northern environment and the realities of a warrior culture, yet they were far more complex than simple “might makes right” philosophy. The Norse cosmos was organized around multiple realms connected by Yggdrasil, the World Tree, and populated by two primary groups of deities.

The Two Pantheons: Aesir and Vanir

The Aesir were the more warlike gods, dwelling in Asgard and led by Odin, the one-eyed seeker of wisdom. This pantheon included Thor (thunder and protection), Frigg (marriage and motherhood), and the complex trickster figure Loki. These deities embodied the harsh realities of survival in a challenging environment—they were powerful but not omnipotent, wise but not all-knowing, and ultimately subject to fate.

The Vanir represented fertility, prosperity, and wisdom, dwelling in Vanaheim and led by Njörðr and his children Freyr and Freyja. These gods governed agriculture, fertility, and the cycles of nature that were essential for survival. The integration of both pantheons through the Aesir-Vanir War (described in the Völuspá) reflected the historical merging of different Scandinavian cultural groups.

Ragnarök and Norse Worldview

Central to Norse religion was the concept of Ragnarök—literally “Fate of the Gods”—a prophesied series of events culminating in the destruction and renewal of the cosmos. This wasn’t simply an apocalyptic vision but reflected a cyclical understanding of time where endings enabled new beginnings. The ship Naglfar, built from the fingernails of the dead, would carry forces of chaos to the final battle.

This cosmic perspective profoundly influenced Norse culture. Knowing that even the gods were subject to fate encouraged a philosophy of living fully in the present moment while accepting the inevitability of change and loss. This worldview fostered both the courage that enabled Viking expeditions and the sophisticated emotional complexity found in Norse literature.

Reflection Question:

Social Structure and Gender Relations

Norse society was notably more egalitarian in gender relations than many contemporary medieval cultures. Women could own property, request divorces, serve as priestesses, and occasionally participate in trade expeditions. Archaeological evidence from graves suggests some women held high status, possibly including the legendary shield-maidens, though the historical reality of female warriors remains debated among scholars.

The relative gender equality in Norse culture reflected practical necessities. With men frequently away on trading voyages or raids, women managed households, farms, and local communities. This economic responsibility translated into social authority that was recognized legally and culturally.

Language, Literature, and Intellectual Traditions

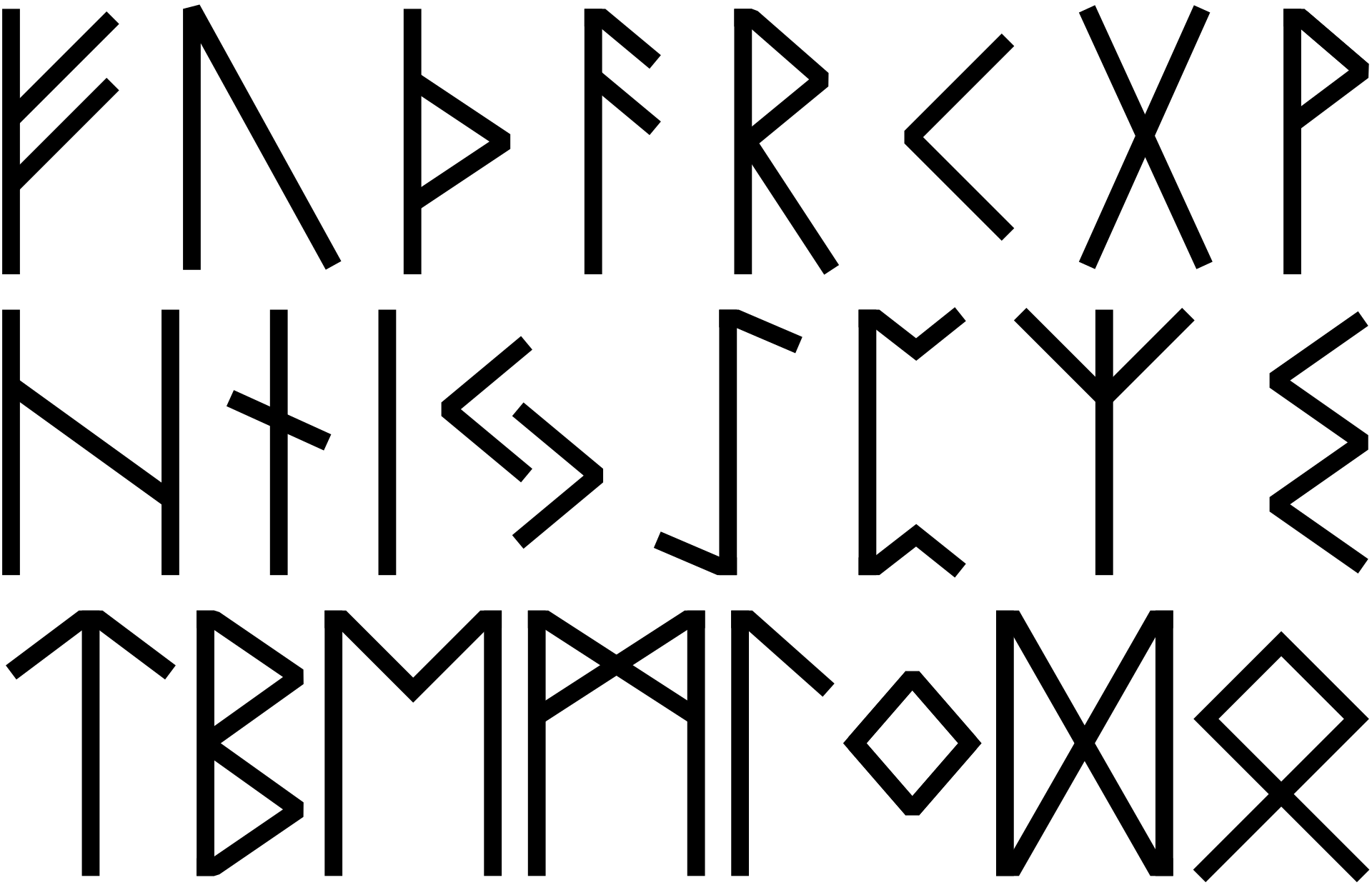

The Runic Writing System

The Norse developed the Elder Futhark, a runic alphabet of 24 characters that served both practical and magical purposes. Each rune represented not only a phonetic sound but also embodied specific concepts or powers. For example, the rune ᚠ (fehu) meant “cattle” or “wealth,” while ᚦ (thurisaz) represented “giant” or “thorn.” This dual nature meant that runic inscriptions could function simultaneously as text and as powerful symbols.

Runes appeared on everything from memorial stones to everyday objects, serving purposes ranging from identification marks to protective charms. The association of writing with magic reflects the Norse understanding that knowledge itself was a form of power—a theme reflected in myths about Odin’s sacrifice to gain wisdom.

Literary Heritage: The Eddas

Our primary sources for Norse mythology come from two medieval Icelandic works:

The Prose Edda (c. 1220 CE) by Snorri Sturluson provides a systematic presentation of Norse mythology, written partly as a guide for poets and partly to preserve cultural knowledge as Iceland Christianized. Sturluson wrote with remarkable literary sophistication, creating a work that functions simultaneously as mythology, poetry manual, and cultural history.

The Poetic Edda (compiled c. 1270 CE, though containing much older material) preserves ancient poems about gods and heroes in their original verse forms. These poems capture the distinctive voice of Norse literature—spare, dramatic, and psychologically complex.

Both Eddas were written after Scandinavia’s conversion to Christianity, yet they preserve pre-Christian traditions with remarkable fidelity. This preservation occurred partly because the myths had become literary rather than strictly religious material, and partly because of Iceland’s unique cultural position as a repository of Scandinavian tradition.

Norse as Explorers and Innovators

Maritime Technology and Navigation

The Norse longship represents one of medieval Europe’s greatest technological achievements. These vessels combined shallow draft (allowing navigation of both open seas and rivers) with remarkable speed and maneuverability. The clinker-built construction—overlapping planks secured with iron rivets—created ships that were both flexible enough to handle ocean swells and strong enough for long voyages. Here is a video from The History Channel that recreates a Viking longship experience. https://youtu.be/yB4s3nQtZqE?si=sVFTGpPY0de2GScE

The Sutton Hoo burial site (though Anglo-Saxon rather than Norse) demonstrates the cultural importance of ships in early medieval Scandinavia. This archaeological site reveals the sophisticated metalwork, social organization, and beliefs surrounding maritime culture.

Exploration and Settlement

Norse explorers achieved remarkable geographical reach. They established settlements in Iceland (870 CE), Greenland (985 CE), and briefly in North America (c. 1000 CE). These expeditions required not only navigational skill but also the social organization to establish sustainable communities in challenging environments.

The Norse expansion wasn’t simply random raiding but followed systematic patterns. They targeted regions that offered specific resources or strategic advantages: Ireland and England for monasteries containing wealth, the North Atlantic islands for land and fishing grounds, and the river systems of Eastern Europe for access to Byzantine and Islamic trade networks.

Art, Architecture, and Material Culture

Norse artistic traditions reflected both their maritime orientation and their complex religious beliefs. The intricate metalwork found at Anglo Saxon sites like Sutton Hoo demonstrates sophisticated techniques in gold and silver working. Norse artisans created elaborate brooches, arm rings, and weapons that served both practical and symbolic functions.

Architecture focused on functionality in harsh climates. The longhouse design maximized warmth efficiency while accommodating extended families and their livestock during winter months. These buildings reflected social relationships, with spatial arrangements indicating status and family connections.

Cultural Connection

Additional Resource: For detailed information about Norse architecture, including longhouses and boathouses, see:

Legacy and Modern Influence

Norse cultural influence extends far beyond historical interest. The democratic assemblies (things) that governed Norse communities contributed to later Scandinavian political traditions. Norse legal concepts, including trial by jury and individual rights, influenced medieval European law development.

In literature, Norse narrative techniques—psychological complexity, tragic heroism, and acceptance of fate—continue to influence modern storytelling. The Norse exploration of themes like loyalty versus personal desire, the relationship between fate and free will, and the nobility found in facing inevitable defeat resonate across cultures and centuries.

Contemporary Cultural Impact

Modern popular culture continues drawing from Norse sources, but often simplifies complex mythological concepts. While Marvel’s Thor films introduce Norse mythology to new audiences, they transform Asgard from a complex cosmos governed by fate into a more conventional superhero setting. Understanding authentic Norse culture allows us to appreciate both what these adaptations preserve and what they change.

Reflection Question

Conclusion: Understanding Norse Culture Today

The Norse developed a remarkably sophisticated culture that balanced pragmatic survival skills with complex artistic and intellectual traditions. Their achievements in exploration, literature, and social organization emerged from the specific challenges of their northern environment, yet their solutions influenced European development for centuries.

Perhaps most importantly, Norse culture demonstrates how societies can maintain cultural coherence while adapting to new circumstances. The same adaptability that enabled Norse settlers to thrive in Iceland and establish communities in Greenland also allowed them to preserve their mythological traditions in Christian contexts. This flexibility offers lessons for our own era of rapid cultural change.

By studying Norse culture seriously—beyond popular stereotypes—we gain insight into human responses to environmental challenges, the relationship between individual achievement and community values, and the enduring power of storytelling to preserve cultural memory across centuries of change.

Putting It All Together

For Further Reading

- Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson (Project Gutenberg)

- Poetic Edda (Internet Sacred Text Archive)

- Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman

- Khan Academy materials on Viking economics and trade

- National Museum of Denmark

- Smart History: “Art of the Viking Age“