1 What’s Wrong with This Picture?

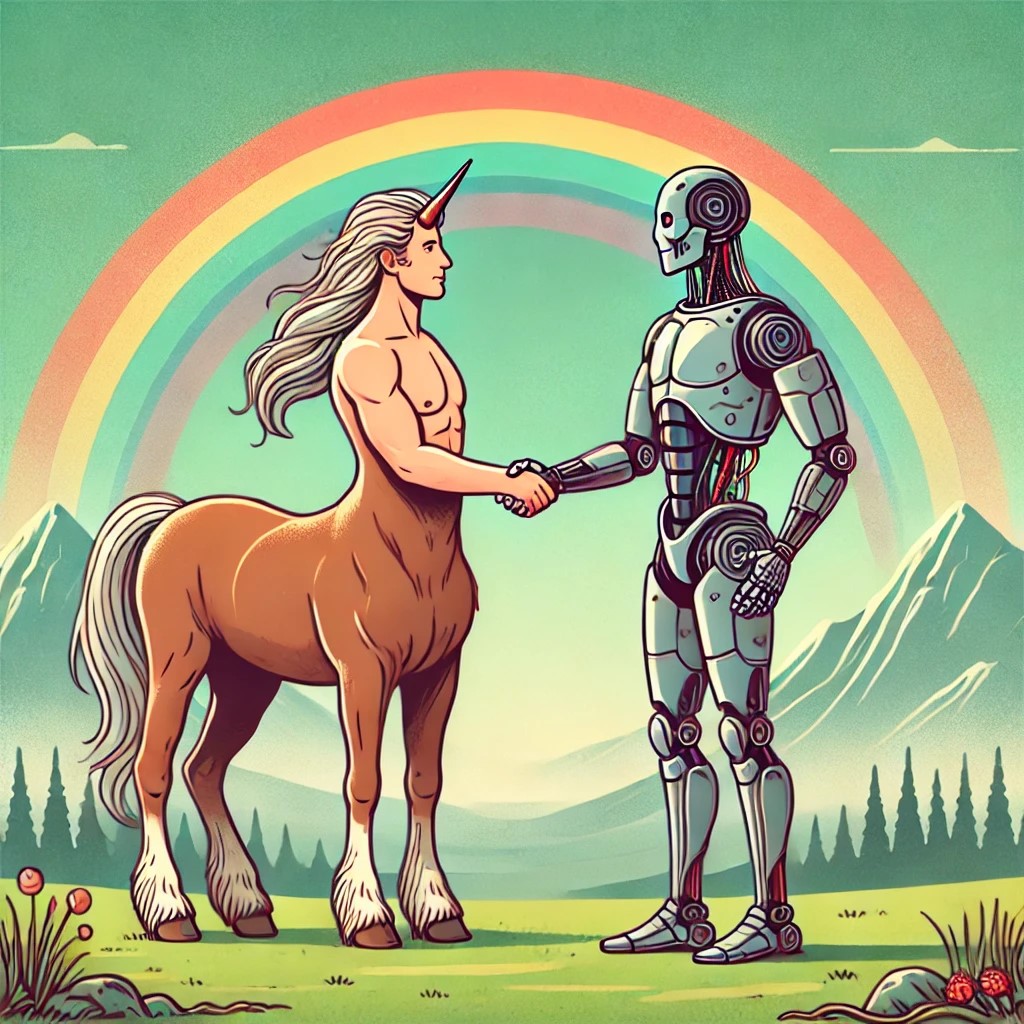

Take a look at the cover image for this textbook. What do you notice?

It’s probably clear to you that I used a generative artificial intelligence tool (DALL-E 3 through ChatGPT 4o) to create this image. I started an entertaining journey of image creation misadventures with this simple prompt:

“Can you please draw an image of a centaur shaking hands with a cyborg? The centaur and cyborg should be in the center of the image, with a rainbow and mountains blurred in the background. Use a high fantasy art style.”

Spoiler alert: It really couldn’t do this. We engaged in a series of back and forths where I tried to teach it what centaurs and cyborgs are, and it told me without blushing that there was no horn on the man’s head. Here’s the version of the prompt I used to get the cover result:

“I want two central images. 1. A centaur. A centaur has a human (man or woman) head and torso and hands. It has a horse’s body, flanks, four legs, and tail. 2. A cyborg. A cyborg is part human and part machine. It has two legs like a human and stands on two legs. Please use a whimsical children’s book illustration style and include a rainbow and mountains in the background” (Open AI, 2024).

What I got instead was this: a mishmash image of a human unicorn/centaur shaking hands with a robot centaur. The rainbow looks good though.

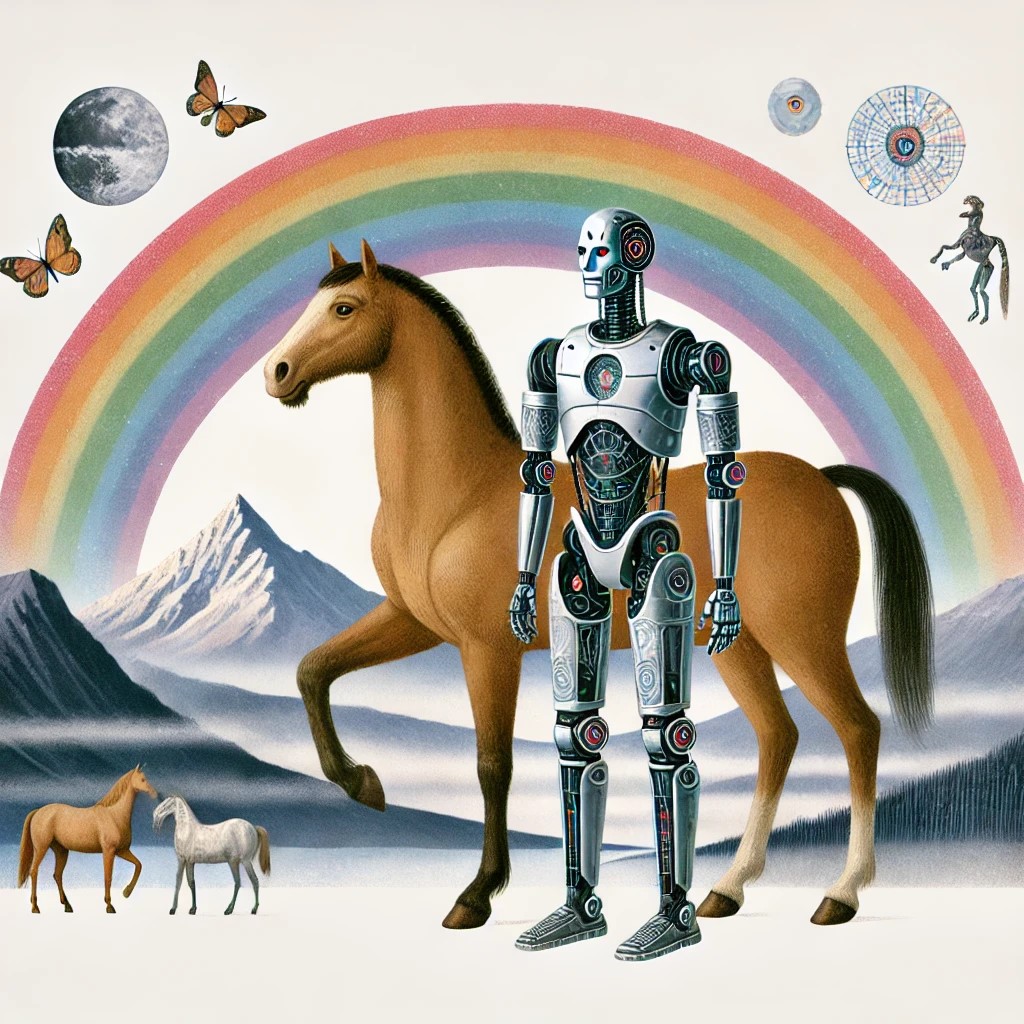

Just for fun, here are a few other things the image generator came up with.

First, here’s an example of AI art that resembles a lot of what I am seeing on the Internet right now. There’s something deeply strange but almost mystical about its strangeness. Someday soon there’ll be a whole scholarly field devoted to interpreting and deciphering generative AI “art.”

The closest the image generator got to my personal vision for the cover is the one below (but the centaur still has a horn on its head. Why???)

My challenges in working with DALL-E 3 to realize my vision for our textbook cover are indicative in many ways of both the promise and pitfalls that working with AI tools bring to the writing classroom. What experiences have you personally had with generative artificial intelligence tools (yes, SnapChat AI counts!)? Are your experiences positive, negative, or a mix? If you’ve never tried an AI tool before, that’s fine too!

Before we learn more about generative AI tools and how they can be used in academic writing, I’d like to know more about where you are at right now with generative artificial intelligence. Please take this five-minute anonymous survey about your experiences with AI.

Centaurs, Cyborgs, and Resisters: Understanding Your AI Style

This section was remixed from “Principles for Using AI in the Workplace and Classroom” by Joel Gladd, CC BY NC.

How you use AI may depend on your comfort level. Some people blend AI seamlessly into their work, while others prefer a clear boundary between human-created and AI-generated content. Some may take a more antagonistic stance towards these tools. In his book Co-Intelligence, which we will refer to throughout this course, Mollick uses the metaphors of centaurs and cyborgs to describe these approaches. We’re adding the third category, resisters.

Centaurs

A centaur’s approach has clear lines between human and machine tasks—like the mythical centaur with its distinct human upper body and horse lower body. Centaurs divide tasks strategically: The human handles what they’re best at, while AI manages other parts. Here’s Mollick’s example: you might use your expertise in statistics to choose the best model for analyzing your data but then ask AI to generate a variety of interactive graphs. AI becomes, for a centaur, a tool for specific tasks within their workflow.

Cyborgs

Cyborgs deeply integrate their work with AI. They don’t just delegate tasks—they blend their efforts with AI, constantly moving back and forth between human and machine. A cyborg approach might look like writing part of a paragraph, asking AI to suggest how to complete it, and revising the AI’s suggestion to match your style. Cyborgs may be more likely to violate a course’s AI policy, so be aware of your instructor’s preferences.

Resisters: The Diogenes Approach

Mollick does not suggest this third option, but we find that it’s important to recognize that some students and professionals feel deeply uncomfortable with even the centaur approach, and our institution and faculty will support this preference as well. Not everyone will embrace AI. Some may prefer to actively resist its influence, raising critical awareness about its limitations and risks. Like the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes, who made challenging cultural norms his life’s work, you might focus on warning others about AI’s potential downsides and advocating for caution in its use. Of course, those taking this stance should understand the tool as well as centaurs and cyborgs. In fact, resisters may need to study Ai tools even more deliberately.

The Future? Hybrid Writing in College Classrooms

This book represents a new type of writing collaboration. I wrote this book with help from Claude, ChatGPT 4o, Microsoft Copilot, and other AI tools. I have also created and incorporated some custom AI tools to help you improve your own writing process and designed activities to use generative AI tools throughout the textbook. This model is what Wharton School of Business Professor Ethan Mollick has termed “co-intelligence.” In his book, Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI, Mollick outlines four basic principles for using generative artificial intelligence tools in writing or other types of work:

- Always invite AI to the table.

- Be the human in the loop

- Treat AI like a person

- The current model of AI that you are working with is the worst AI you’ll work with in your life (Mollick, 2024).

Because I like to read science fiction and fantasy, I’m calling this “co-intelligence” writing textbook Cyborgs and Centaurs. As the generative AI text-to-image prompt above explained, cyborgs are hybrid creatures–half human and half machine. And centaurs are also hybrid creatures–half human and half magic. In my own experiences working with generative AI tools since late 2022, I have found that both concepts reflect how I feel about writing with AI.

In this book, we will explore how to apply Mollick’s principles as we learn to become academic thinkers, researchers, and writers. We will learn where AI can be helpful–and where it can be harmful. We’ll consider the ethics of using generative AI. And we’ll practice specific use cases where AI can improve our writing processes.

I hope we’ll have some fun along the way.