3 What Do You Want to Know?

Inquiry—asking a question—is the heart of academic research. From first-year research papers to doctoral dissertations, we start our research by asking a question. Academic research writing is the process of developing a research question and using high-quality evidence to answer the question. This skill is used in every area of academic life from general education courses to research projects within your major field of study. Inquiry is essential to the goals of scholars and writers because it helps us to better understand problems that affect us and our societies and to contribute to the body of knowledge in the world. This chapter will introduce you to using research for academic inquiry and suggest ways that you can use generative artificial intelligence tools to narrow and focus your research questions.

Key Characteristics

Writing for inquiry, also known as academic research writing, generally includes the following elements:

- Research Question: From projects written in first-year composition courses to doctoral dissertations, academic research projects seek to answer a research question. This question is focused. It’s a question that can be answered through research. And it has some kind of significance to both the author and the readers.

- Evidence: Academic research projects rely almost exclusively on evidence in order to answer the research question. “Evidence” may include both primary sources like interviews, field research, experiments, or primary texts and secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles or other high-quality sources.

- Citation: Academic research projects use a detailed citation process in order to demonstrate to their readers where the evidence came from. Unlike most types of “non-academic” research writing, academic research writers provide their readers with a great deal of detail about where they found the evidence they are using. This processes is called citation, or “citing” of evidence. It can sometimes seem intimidating and confusing to writers new to the process of academic research writing, but citation is really just explaining to your reader where your evidence came from. Citation styles are specific to academic disciplines. Common citation styles in college writing courses include MLA, APA, and Chicago. In our course, we will be using APA style.

- Objective point of view. Though you likely have opinions about your topic, it’s iimportant for academic research writers to remain objective in their approach to the subject. Stay away from “both sides” types of questions because you are not arguing or defending a thesis in this type of essay. Instead, your thesis statement will broadly answer your research question.

Academic Research Writing: What IT’S NOT

- While poets, playwrights, and novelists frequently do research and base their writings on that research, what they produce doesn’t constitute academic research writing. For example, the Broadway musical Hamilton incorporated facts about Alexander Hamilton’s life and work to tell a touching, entertaining, and inspiring story, but it was nonetheless a work of fiction since the writers, director, and actors clearly took liberties with the facts in order to tell their story. If you were writing a research project for a history class that focuses on Alexander Hamilton, you would not want to use the musical Hamilton as evidence about how the Founding Father created his economic plan.

- Essay exams are usually not a form of research writing. When an instructor gives an essay exam, she usually is asking students to write about what they learned from the class readings, discussions, and lecturers. While writing essay exams demand an understanding of the material, this isn’t research writing because instructors aren’t expecting students to do additional research on the topic.

- All sorts of other kinds of writing we read and write all the time—letters, texts, social media posts, chats with chatbots, emails, journal entries, instructions, etc.—are not research writing. Some writers include research in these and other forms of personal writing, and practicing some of these types of writing—particularly when you are trying to come up with an idea to write and research about in the first place—can be helpful in thinking through a research project. But when we set about to write a research project, most of us don’t have these sorts of personal writing genres in mind.

So, What Is “Research Writing”?

Research writing is writing that uses evidence (from peer-reviewed journals, scholarly books, magazines, the Internet, interviews with experts, etc.) to answer a research question.

In the real world, research writing exists in a variety of different forms. For example, scholars or other researchers conduct primary research and publish the results in peer reviewed journals. Scholars, journalists, or other researchers may also publish inquiry-based articles in more popular places such as newspapers or magazines.

Academic research writing—the sort of writing project you will write in this class—is a form of research writing. Students use research writing in a variety of courses and contexts.

Asking the Right Question Matters

Think back to our the prompting exercise in chapter one. No matter how hard I tried, I could not create a narrow, focused prompt that would get DALL-E3 to generate a picture of a centaur. The first step of exploratory writing in many senses is the most important. The success of your exploratory research essay depends on developing a narrow, focused research question. If you don’t ask the right kinds of questions, you may find yourself experiencing the same frustration I felt when I couldn’t get the image I wanted. The more time and effort you spend thinking about how to create a question or series of questions from a topic that interests you, the more successful you are likely to be when you write your research paper.

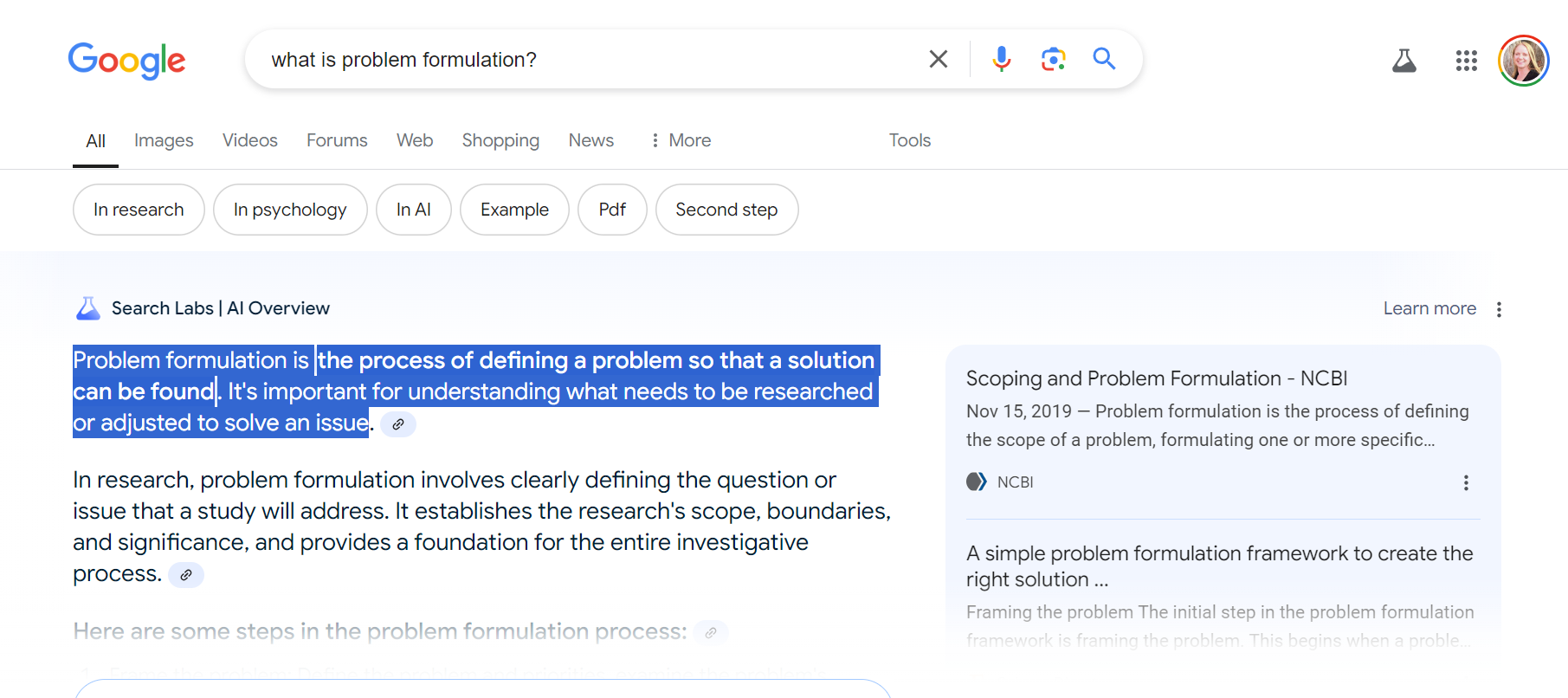

Thinking about topics that interest you is the first step for academic research. And learning to write good research questions will help you to be a better prompter when using generative artificial intelligence tools in the workplace because creating a question is an example of a durable skill called problem formulation. Problem formulation is the process of defining a problem so that a solution can be found. It’s important for understanding what needs to be researched or adjusted to solve an issue (Google Gemini, 2024).

Knowledge Check

If you use Google Search, you may see an AI powered response to your search question. In this case, I asked Google to define problem formulation. How can I tell whether this response is reliable? If I had doubts, what credible source could I check to confirm the definition?

English: The Hottest New Programming Language

Before we get started, I think you should know that according to former OpenAI employee and software developer Andrej Karpathy, “English is the hottest new programming language.” I wanted to demonstrate this for you at the beginning of the course to give you an idea of how powerful these new tools can be. Keep in mind that I’m an English professor. I did take a few programming courses in high school, and I created a somewhat sketchy personal website from scratch back in 2001 (now defunct), but I am not a coder by any stretch of the imagination.

But I am not afraid to use my words to ask for what I want. Watch this short video to see how Claude.ai can help you to take a broad topic and narrow/focus your research question.

One thing I learned in this exercise was that having subject matter expertise (knowing how to do something really well) definitely matters when using generative AI tools. I feel comfortable and confident when using these tools to assist my writing because I am a confident and capable academic writer. I have published a book with Penguin and written for numerous professional publications. I have also written a doctoral dissertation. I can trust my own professional judgment and expertise when evaluating writing output from a chatbot.

But when it comes to evaluating code, I am much less confident. Maybe that’s how some of you feel when you use chatbots for writing tasks. For example, in this exercise, the Python script did exactly what I wanted it to do, but if I had felt more comfortable editing code, I would have made some minor changes to the React interactive tool. I would have cleared the previous answers, for example, and I would have changed the final output to better reflect all the work in the multi-step activity. Iterative prompting—the process of asking the chatbot again when you don’t get what you want—is important when you interact with these tools.

And as you can see, subject matter expertise still matters. It may be more important than ever for you to become an expert in your future field. This reinforces the idea that we should use generative AI tools to augment, not to replace, our own work.

Crafting Your Narrow, Focused Research Question

As you can see from the video, chatting with a generative AI tool like Microsoft Copilot, Claude, ChatGPT, or even Snapchat AI can help you to narrow and focus your ideas. In this case, Claude has provided us with a good set of questions.

- Start broad, then narrow down: Begin with a general topic of interest, then progressively refine it.

- Make it personally relevant: Choose a topic that relates to your experiences, interests, or goals.

- Use the “5 W’s and H” approach: Ask who, what, when, where, why, and how to explore different angles.

- Ensure it’s specific and manageable: The question should be answerable within the scope of your assignment.

- Frame it as a question: Phrase your topic as an open-ended question to guide your research.

- Consider current debates: Look for ongoing discussions or controversies in your field of study.

- Use limiting words: Incorporate terms like “specific,” “particular,” or date ranges to narrow the focus.

- Test for researchability: Ensure sufficient sources are available to answer your question.

- Avoid yes/no questions: Opt for questions that require analysis and explanation.

- Get feedback: Share your question with peers or instructors for input (Claude.ai, 2024).

Claude created this simple flowchart to help you visualize the steps of the research process. And here’s a link to the interactive tool Claude created so that you can test out your own research question.

For your writing task this week, you’ll be following this process to create a narrow and focused research question for instructor approval. You’ll also get generative AI feedback on your question. Make sure you include two-three paragraphs explaining why you are interested in this question and how it connects to you personally. I recommend looking for a topic that has debatable aspects because you can use the same topic for both your first and second essays, though these will be very different papers.