36 WESTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Islamic Architecture

- Blue Mosque

- Hagia Sophia

- Jewish Architecture

- Eliyahu HaNavi Synagogue

- Bayit Farhi

- Islamic Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

Ottomans

The Ottoman Empire was the foremost and longest-lived of the Islamic empires of the early modern world. It was formed by a small group of Turkic-speaking warriors assisted by Anatolian and Balkan Christian warlords and their followers at the end of the thirteenth century. For nearly seven hundred years, the Ottoman state lay at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, ruling over a population diverse in ethnicity, language, and religion. In 1453, the Ottomans conquered Constantinople. A century later, the city, then called Istanbul, was one of the largest in the world, occupying a prize position on the Bosporus, the sea passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and facilitating trade between the Silk Roads and Europe. At its height under Sultan Suleiman I in the sixteenth century, the Ottoman military was the most technologically advanced in the Mediterranean world, threatening the gates of Vienna to the west, reaching the Persian Gulf to the east, and conquering Yemen and the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina to the south (Figure 4.11). In the seventeenth century, as its enemies grew stronger, the empire became more inward-looking, focusing less on external expansion and more on resolving domestic affairs, professionalizing its bureaucracy, and conducting internal reforms.

The Ottomans brought knowledge of horses, military organization, and statecraft to their early empire. They followed their Seljuk predecessors in holding Persian culture and style in high esteem. While Arabic was considered the language of learning and religion, Persian was often the language of poetry and literature, even in the otherwise Arabic-speaking court of the Abbasid caliphs. The Ottoman Empire is often described as Persianate, meaning its culture, including visual art and architecture, was heavily influenced by that of Persia, but it was not Persian itself (Figure 4.13). Turkish was the language of administration and education; it was written in an adapted version of the Perso-Arabic script, and it incorporated numerous loan words from both Persian and Arabic. A parallel tradition of high poetry in Turkish called divan poetry also developed, which used the rhyme schemes and poetic meters of Persian poetry. In the seventeenth century, during the long conflict between the Ottomans and the Safavids in Iran, Turkish replaced Persian as a literary language, to emphasize the Turkish nature of the Ottoman state and distinguish its culture from that of its rival.

The Ottoman state’s geographic position was an important advantage from its beginning well into the height of its power in the seventeenth century. The early empire was born on the dividing line between Europe and Asia and balanced between them for nearly its entire existence. The collapse of the Byzantine Empire allowed the Ottoman sultan to rule from a capital city situated between the two continents. After establishing his new capital in Istanbul, Mehmed II issued a call for citizens of the empire to come and settle there to restore its economic vitality (Figure 4.16). This was necessary because the city had experienced steady demographic decline over the previous few centuries. At first, Mehmed offered free housing to anyone who moved there voluntarily; later, he ordered thousands of Serbs, Armenians, Greeks, Jewish people, and Turks to settle in the city. Although he would not live to see it, within a century Istanbul was by far the largest city in Europe, with nearly a half million residents, and it dominated the land and sea trade between Europe and Asia.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). The Ottoman Empire. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

Safavids

To the east of the lands of the Ottomans, another Islamic empire emerged at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Based in Iran, the Safavid Empire at its height ruled over much of what is now Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Georgia, and Iraq, as well as parts of several neighboring countries including Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan (Figure 4.19). Like the Ottomans and Mughals, the Safavids developed a powerful military, ran a strong and well-organized central state, and fostered a climate in which artistic and intellectual culture flourished. The Safavids also introduced Shi‘ism as the state religion at a time when Iran’s population was mostly Sunni, and in doing so they fostered the deep divisions between Shi‘ism and Sunnism that continue to characterize relations between Iran and other Islamic nations today.’

Initially, like most of Iran’s population, the Safavids were primarily Sunni Muslims. Like that of many Sufi orders, their ideology incorporated elements of both Sunni and Shia doctrines to proclaim a universal message and attract followers from both sects. However, Safi al-Din’s great-grandson Junayd made several changes to the order’s doctrine, adopting specifically Shia ideas. Junayd believed the Safavids should use their popular religious mandate to seek military and political power for themselves, and he found Shia doctrine more appropriate for his vision.

Junayd’s son Haydar created a solid political and military framework by establishing a Safavid military order known as the Qizilbash, after their distinctive red hats (qizil means “red” in Azeri). Haydar declared a religious war against the Christian residents of the Caucasus, but in order to reach them, he had to pass through the territory of the Shirvanshahs, who were allied with his enemies. Although at first he was able to negotiate safe passage for his army, the Shirvanshahs, already uneasy about Haydar’s growing power, used his eventual attack on one of their cities as an excuse to declare war on the Safavids. Haydar was killed in battle in 1488. His son Ali Mirza took his place, but within a few years his capital at Ardabil was conquered by his enemies. Ali Mirza was also killed, and his infant brother Ismail was sent into exile.

After being sheltered by allies, the twelve-year-old Ismail emerged from exile in 1499 claiming to be the Mahdi or messiah and began rallying the Qizilbash troops who had fought for his father and brother. They embarked on a military campaign, winning victory after victory until, in July 1501, Ismail entered the Shirvanshah capital of Tabriz and declared himself shah, or emperor, of all Iran (Figure 4.20). At the time, he governed only Azerbaijan and part of the Caucasus. By 1511, however, Ismail’s troops had driven the Uzbek people across the Oxus River, establishing the eastern borders of modern Iran. The Safavids also staged incursions into eastern Anatolia; these triggered a conflict with the Ottoman Empire that continued for the length of the Safavids’ reign. Not only had Ismail’s forces occupied the empire’s border cities, but he had begun recruiting for his army among the ethnic Turkish tribes of eastern Anatolia and encouraging the Shia Muslims in Ottoman lands to revolt against their Sunni rulers.

Shi‘ism was not officially tolerated by the Sunni caliphs of the Umayyad and Abbasid Empires because of its perceived challenge to their rule. For this reason, most Shia movements developed far outside the control of these caliphates, in places like Morocco, Yemen, Iran, and central Asia. After the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258, the Sunni caliphate became a weak figurehead position that held only symbolic authority. During the period of Mongol rule over Iran and the Caucasus, the distinction between Shia and Sunni became less important than it had been. When Ismail crowned himself Shah in 1501, most of Iran’s population was Sunni. When he declared Twelver Shi‘ism to be the state religion of Iran, he hoped to unify his Iranian subjects by having them adopt a form of Islam that gave them a unique identity and distinguished them from their military and political enemies the Ottomans and the Uzbeks, who were both Sunni.

Historians generally agree that the Safavids’ efforts to convert Muslims in their empire to Shi‘ism utilized coercion and force. Shah Ismail, who saw himself as infallible and semidivine, believed his strong religious convictions had won him the Iranian throne, and he used his political and military authority to impose his religious ideology on the country (Figure 4.23). He ordered all Iran’s Sunni Muslims to become Shi‘ites. Sunni clerics and theologians were given the choice of conversion or exile. Sunnis who resisted conversion but remained in Iran faced death. To spread the new beliefs and win converts, Ismail brought Shia scholars to Iran from Lebanon and Syria. He used state funds to construct schools where Shia beliefs were taught and to build shrines to Ali and members of his family. Ismail also invited foreign Shi‘ites living in places where they were persecuted by the Sunni majority to move to Iran, promising them land and protection.

The Safavids were generally more tolerant of non-Muslim subjects than they were of the Sunni. Nevertheless, Safavid rulers were aggressive toward the Armenians, Georgians, and other Christians in the Caucasus region, whom they considered potentially rebellious. They sought to control these populations by enslaving or deporting their members, and nobles were often requested to convert to Shi‘ism. Christians elsewhere in the Safavid realm, however, were given considerable freedom to build churches and honor their own customs and beliefs. Abbas I was particularly lenient toward the Armenian Christian population of Isfahan, due to their participation in the lucrative manufacture and export of silk. Spain and the Vatican sent several embassies to Iran hoping to enlist it as an ally against the Ottomans. The pope also hoped Abbas would allow the construction of a cathedral in his new capital city of Isfahan, but on their arrival his emissaries found three Roman Catholic churches already there (Figure 4.24).

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Muslim Scientists

As the Ottoman state grew in prestige and size, its sultans deliberately set out to become patrons of science and learning, following the examples set by the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs and other prominent Muslim leaders. The core of all education was religious; there was no separation between what today would be considered religious philosophy or doctrinal study and the “hard sciences” such as astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, and physics. On the contrary, scientific investigation was considered an act of devotion because of its exploration and discovery of the intricacies of the divinely created universe.

From the very beginning of the state, institutions of higher learning—madrasas—were established in major cities. Patronage of science, art, and culture reached a new level under Sultan Mehmed II. Mehmed founded the first institution of higher learning in the new capital, the Fatih complex, which included a hospital, public kitchens, a library, and schools. The Fatih hospital remained operational into the nineteenth century.

As Istanbul developed as the imperial capital, many other such institutions came to be established there. Another complex of charitable institutions, the first one designed and built in Istanbul by Mimar Sinan, the master architect and engineer of Armenian origin, was a teaching hospital endowed by Hurrem Sultan, the wife of Sultan Suleiman. It was also common for wealthy Jewish and Christian patrons to establish their own vaqfs to fund projects that benefited their communities, because these trusts were exempt from inheritance taxes. Teaching hospitals were considered important recipients of vaqf funds given that hospital care was provided free of charge.

The geographic diversity of the empire was an advantage to the development of medical science because it was now possible to compare the results of medical treatments and experiments in several different geographic and climate zones. For this reason, many important medical treatises of the day were written in the Ottoman Empire. The tradition of medical writing built upon the foundation established by such famous Muslim scholars and physicians as Ibn Sina, who composed The Canon of Medicine in the tenth century. The works produced by physicians who made their home in the Ottoman Empire included one of the first treatises dedicated to dentistry, written by the Spanish Jewish scholar Musa bin Hamun, who made his home in the Ottoman Empire after the Jewish people were expelled from Spain.

Among the great scientists of the Ottoman Empire was Taqi al-Din, who was invited by Sultan Murad III to build an observatory in Istanbul (Figure 4.18). Taqi al-Din’s method of calculating the coordinates of stars is said to have been better than those of Tycho Brahe and Nicolas Copernicus, noted astronomers working in northern Europe around the same time. Taqi al-Din also developed steam turbines and mechanical clocks and conducted research into the optical refraction of light. His work illustrates the way scientific discoveries transcended religious and national divisions; he himself had set out to improve on astronomical techniques devised by Ulugh Beg at Samarkand (in today’s Uzbekistan), and in turn his own research was consulted by Tycho Brahe in Denmark when Brahe was developing his ideas about astronomy. Taqi al-Din’s works were also collected by the Dutch mathematician Jacob Golius, who brought them to the library of Leiden University in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). The Ottoman Empire. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

LITERATURE

The Book of Suleiman

The Suleymanname. Persian literary and artistic styles greatly influenced the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century. This illustration, made in the style of a Persian miniature, is part of the Suleymanname (The Book of Suleiman), created at the court of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1561. It includes verses written in Persian by the poet Fethullah Çelebi. (credit: “Sueleymanname nahcevan” by Unknown/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The Süleymannâme is the fifth volume of the Shahnama-yi Al-i Osman (The Shahnama of the House of Osman) written by Arif Celebi. It is an account of Suleiman’s first 35 years of his reign as ruler from 1520 to 1555. The portrayal of Suleiman’s reign is idealized, as it not only includes the last exceptional events in world history, but also ends the timeline begun at creation with this perceived perfect ruler. The manuscript itself measures 25.4 by 37 centimeters and has 617 folios. In addition, it is organized in chronological order. This manuscript had a much more private use compared to other pieces of art produced for the Ottoman elite. The Süleymannâme has 69 illustrated pages since four topics out of the 65 represented are double-folio images. The cultural and political context of this work is Persian. This work is important because it allows for the acceptance of the sultan presenting himself in a divine image as well as presenting the ideas and expectations of the court. Arifi wrote in this epic poem 60,000 verses. is an illustration of Suleiman the Magnificent’s life and achievements. In 65 scenes the miniature paintings are decorated with gold, depicting battles, receptions, hunts and sieges. Written by Fethullah Arifi Çelebi in Persian verse, and illustrated by five unnamed artists

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). The Safavid Empire. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

Copyright: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Tughra (Official Signature) of Sultan Süleiman the Magnificent from Istanbul,” in Smarthistory, January 25, 2016, accessed May 16, 2024,

Video URL: https://smarthistory.org/tughra-official-signature-of-sultan-suleiman-the-magnificent-from-istanbul/.

ARCHITECTURE

Islamic Architecture

The Hagia Sophia as a Mosque

Video URL: https://youtu.be/r6383ZDXB0Q?si=RRxia5Ot0N-IRTmH

Copyright: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Hagia Sophia as a mosque,” in Smarthistory, June 18, 2018, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hagia-sophia-as-a-mosque-2/.

The Blue Mosque

The Sultan Ahmet Mosque, popularly known as the Blue Mosque, was completed in 1617 just prior to the untimely death of its then 27-year-old eponymous patron, Sultan Ahmet I. The mosque dominates Istanbul’s majestic skyline with its elegant composition of ascending domes and six slender soaring minarets. Although considered one of the last classical Ottoman structures, the incorporation of new architectural and decorative elements in the mosque’s building program and its symbolic placement at the imperial center of the city point to a departure from the classical tradition innovated under the famous 16th-century master architect, Mimar Sinan.

A symbolic location

The mosque’s site is politically charged. Unlike other Ottoman imperial mosques, which were placed farther away from the city center to encourage urban development and to take advantage of Istanbul’s hilly topography, the Sultan Ahmet mosque is nestled in between the Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Hippodrome near the Ottoman royal residence, Topkapı Palace. In fact, the choice of location caused some consternation since it required the demolition of quite a few established palaces owned by Ottoman ministers. But prestige outweighed the enormous cost in coin and real estate. Constructing large mosque complexes for the benefit of the public was part of the imperial tradition denoting a pious and benevolent ruler. Placing the mosque adjacent to the Hagia Sophia also signified the triumph of an Islamic monument over a converted Christian church, a matter of great concern even 150 years after the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul in 1453.

The rivalry between the two monuments is difficult to ignore as you alight from the tram and walk towards them today. Both buildings overwhelm with their massive proportions and their individual claims on the city’s history. But the Sultan Ahmet mosque is distinct from the 6th-century church. The mosque features two main sections: a large unified prayer hall crowned by the main dome and an equally spacious courtyard. In contrast to earlier imperial mosques in Istanbul, the monotony of the exterior stone walls is relieved through numerous windows and a blind arcade. Huge elevated and recessed entrances penetrate three sides of its precinct to provide access to the sacred core. The courtyard’s inner frame is a domed arcade, which is uniform on all sides except for the prayer hall entrance where the arches expand.

Inside, the central dome rests on delicate pendentives (triangular segments of a spherical surface) with its weight supported on four massive fluted columns. In order to extend the prayer space beyond the span of the central dome, a series of half-domes cascade outwards from the center to ultimately join the exterior walls of the mosque. Of the six minarets (towers traditionally built for the call to prayer), four are positioned on the corners of the mosque’s prayer hall while the other two flank the external corners of the courtyard. Each of these “pencil” minarets has a series of balconies adorning its lean form.

Six minarets were unusual even for an imperial mosque—they implied equality with the multi-minareted mosques of Mecca leading to considerable resistance from the local population. The solution? Legend has it that in an attempt at appeasement, a seventh minaret was added to the mosque in Mecca, proving its primacy over any imperial mosque in Istanbul or elsewhere. But evidence to support this claim is thin since some believe the seventh minaret already existed prior to the Blue Mosque’s construction while others cite a much later date for the seventh minaret’s addition.

The interior

The prayer hall itself is punctuated with several architectural features including the sultan’s platform and an arcaded gallery running along the interior walls except on the qibla wall facing Mecca. A carved marble niche set into the center of this wall guides the faithful to the correct direction for prayer. To its right is a tall and thin marble pulpit (minbar) capped with an ornamental turret.

Tilework and stained glass

Upper sections of the mosque are painted in geometric bands and organic medallions of bright reds and blues, but much of this is not original. Rather, the careful choreography of more than 20,000 Iznik tiles rise from the mid-sections of the mosque and dazzle the visitor with their brilliant blue, green, and turquoise hues, and lend the mosque its popular sobriquet.

Traditional motifs on the tiles such as cypress trees, tulips, roses, and fruits evoke visions of a bountiful paradise. Sultan Ahmet requisitioned these specifically for the building. The lavish use of tile decoration on the interior was a first in Imperial Ottoman mosque architecture. The intensity of the tiles is accentuated by the play of natural light from more than 200 windows that pierce the drums of the central dome, each of the half-domes, and the side walls. These windows originally contained Venetian stained glass.

Copyright: Dr. Radha Dalal, “The Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmet Camii),” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-blue-mosque-sultan-ahmet-camii/.

Jewish Architecture

Eliyahu HaNavi Synagogue

Video URL: https://youtu.be/m-Ox1qaPXew?si=WB0yHPzkALTG7exE

Copyright: Jason Guberman-Pfeffer and Dr. Beth Harris, “Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue, Jobar (Syria),” in Smarthistory, January 10, 2018, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/diarna-documenting-places-vanishing-jewish-history-2/.

Bayit Farhi

Video URL: https://youtu.be/7lmiCMCSizY?si=lASpQJCNXztWhSlj

Copyright: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Bayt Farhi, a Jewish house in Damascus,” in Smarthistory, October 16, 2020, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/bayt-farhi/.

PERFORMING ARTS

Dervishes

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Ywa6glFr6io?si=Mk2Nzyf5TPEb-5pF

The two largest sects of Islam are Sunni (roughly 80% of Muslims) and Shia (roughly 15% of Muslims). Within the Sunni sect, a small sub-sect exists known as Sufism. All Sufis belong to certain orders, each with their own traditions and practices. Among these orders is a small but impactful religious order known as the Mevlevi order, predominantly from Turkey. The Mevlevi are adherents of the teachings of a Muslim mystic from the 13th century named Rumi. His teachings and the practices of the Mevlevi order are considered mystical and their beliefs are quite spiritual in nature.

The most noticeably visible practice of the Mevlevi is a ceremony called Sema (or Sama). This ceremony is an example of an Islamic devotional act. Practitioners of the Sema are initiates to the Mevlevi order and are traditional male only. The video below shows a performance of the Sema ceremony, often referred to in the West as the “Whirling Dervishes” — an exoticized name used as a marketing term to attract tourists to performances. “Sema” means “listening” as meant to be a dance of deep meditation to honor God. Everything seen in the video is highly symbolic.

The dark cloak shields the practitioner from the world, as he removes this cloak, he may begin the dance. The tall brown hat represents a tombstone and marks the intentional death of one’s ego. The stark white skirt represents the shroud of the ego, trying to hide it from God. As the dance begins the practitioner has a closed posture symbolizing the closeness to God. Once the spinning begins, the arms outstretched. One reaching up to God to receive his blessing, the other palm facing the ground the transmit God’s power to the Earth.

As the practitioner reflects on the texts being recited, he prepares for the dance. This performance of text enables a state of meditation. Through the meditative action of dancing, the physical reaction to reach to God and bring blessings to the Earth enables a repetition of this act to bring a heightened state of consciousness in spirituality.

Copyright:This page titled 6.1: Sema is shared under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Justin Hunter and Matthew Mihalka (University of Arkansas Libraries) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform; a detailed edit history is available upon request.

VISUAL ARTS

Carpet weaving

Carpets are woven works of art that were produced at every level of society in the Islamic world. Women have been weaving for centuries in villages and nomadic encampments all over the West Asia, Anatolia, and Central Asia, each woman passing down her techniques and designs to her daughters. These women created carpets both for sale and for their own personal use, and this tradition continues today.

Carpets were also made in the royal courts of the Islamic world. These carpets were not just functional floor coverings, they were ornate works of art that indicated the status and wealth of their owners. Court carpets were used on the floors in reception halls, audience chambers, and at court-supported religious institutions. They were also presented as impressive gifts to other rulers. Manuscript paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries suggest smaller rugs were often layered on top of larger carpets and also show that many carpets were used in outdoor pleasure pavilions and palatial parks.

Rulers had access to expensive materials, such as silk and metal-wrapped threads, and employed the most highly skilled designers and weavers in their empires to create enormous and luxurious carpets. Because of their quality, design, and skilled execution, court carpets are among the finest examples of art from the Islamic world. Court carpets are often very different from the carpets made in commercial workshops or villages. Rather than solely utilizing centuries-old traditional motifs, court carpets often share designs found on a range of media, such as bookbinding and manuscript painting.

Ottoman court carpets

The Ottoman Empire originated in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), and was one of the largest and longest lived in the Islamic world. It controlled territories that reached from North Africa to Eastern Europe. Anatolia has a long tradition of carpet weaving, but from the 16th century onward, Ottoman court carpets utilized a set of specific designs created by the artists of the Ottoman court workshops, designs that were also used on the court ceramics, paintings, bookbindings, and textiles.

Among the most popular of these was the “saz style,” which is characterized by long sinuous leaves, and stylized flowers. Court artists also developed the “floral style,” where we see more naturalistic depictions of flowers such as tulips, roses, carnations, and hyacinths, among others. The floral and saz styles were sometimes used alone and sometimes used together, along with other motifs like the Chintamani pattern (usually a combination of pearl-like circles accompanied by wavy lines sometimes called “tiger stripes”), on a huge variety of objects designed by the court, including ceramics, silks, carpets, and manuscripts.

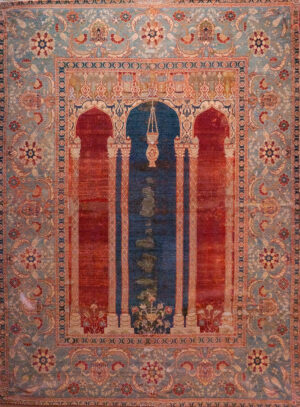

Both the saz and floral styles appear on this rare Ottoman court prayer rug. The jagged-edged saz leaves gracefully undulate in the border amongst carnations, tulips, and other flowers. The arch at the center of the carpet identifies this as a prayer rug, and symbolizes both a mihrab (from mosque architecture) and a gateway to paradise. Such rugs were, and are, used by Muslims during the five daily prayers prescribed in Islam. Though one can go to mosque during the prayer times, prayer can take place anywhere so long as there is a clean surface (provided by the rug) and water for ritual cleansing. A luxurious prayer rug like this would have belonged to a very wealthy court patron.

The design of this remarkable carpet, the prototype for later designs, may be based on the slender-columned architecture of Muslim Spain. When Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492 (and Muslims not long after), many exiles settled in the Ottoman Empire, bringing with them their own visual culture, which, in turn, influenced Ottoman art. This dual-columned design spawned an entire genre of architecturally inspired prayer rugs across Anatolia.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Ottoman court carpets is their unusual structure. Unlike all other Turkish carpets, Ottoman court carpets use S-spun wool, which is typical only of carpets woven in Egypt. Scholars attribute this unusual feature to the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, after which the Ottoman court commissioned carpets from Egyptian workshops and had Egyptian weavers and Egyptian wool sent to Turkey for their own use.

Contemporaneous manuscript illustrations shed light on how carpets were used at the court. Though we must remember that paintings are not photographs, and that artists may have invented much in their scenes, paintings like this can nevertheless tell us about the status of carpets in the court. In this painting, ordered by Sultan Murad III, a Safavid dignitary is presented to the Ottoman sultan against the backdrop of a magnificent red and blue Ushak medallion carpet. The painting shows how carpets were used as decorative and symbolic backdrops to Ottoman court rituals. Not only does the carpet provide a sumptuous setting for the ceremony, it also sends a message to the Safavids (political rivals of the Ottomans) about the wealth of the Ottoman court. We can imagine how such a carpet was used to demonstrate to visitors the power, culture, and artistic accomplishments of the Ottomans.

Safavid court carpets

The Safavids ruled Greater Iran from the early 16th to the 18th century and were avid patrons of the arts. Safavid court carpets are noted for their detailed precision, sumptuous materials, and ornate designs.

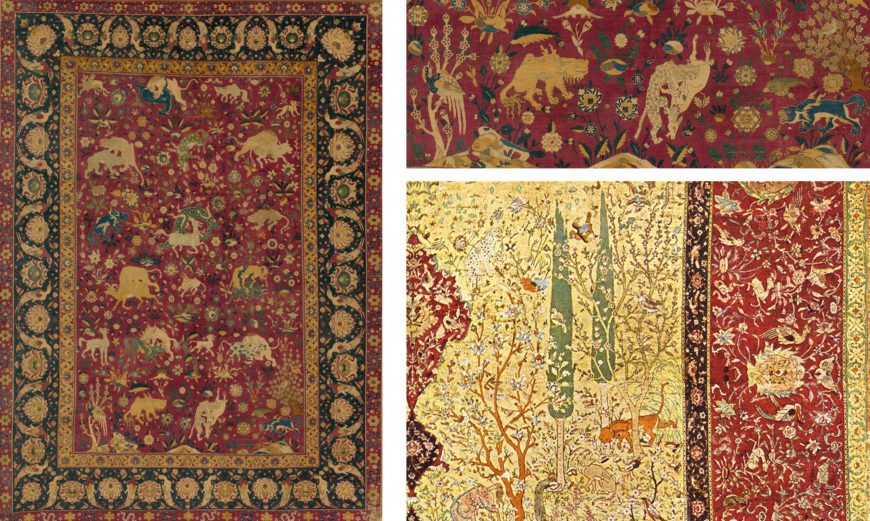

Carpets intended for religious settings, like the Ardabil carpet, display non-figural decoration such as scrolling vines, flower motifs, calligraphy, and shamsas (sunbursts). Carpets made for secular settings, like the court’s palaces and pleasure pavilions, display a wider range of motifs, encompassing the designs found on carpets like the Ardabil, but also sometimes including animals, hunting scenes, human figures, and even angels.

A carpet likely from Kashan is a remarkable example of a secular Safavid court carpet. It was woven entirely of silk, and its bright field is filled with animals—some real, like lions and rams, and others entirely fantastical. The animals, some of which are engaged in intense combat, are set amongst a lush backdrop of stylized flowers and trees. The popularity of animal and hunting scenes was well established in Iran; hunting was considered a princely pastime in Iran even before the advent of Islam, and continued as a widely used subject in Safavid art.

Large scale carpets were produced by court workshops, often with similar subjects and motifs. The fragment left displays the type of central medallion seen in the Ardabil carpet, but its field and borders are filled with birds, roaming animals, and naturalistic landscape elements. Carpets like this fragment are appropriately called “paradise carpets,” reflecting their lush designs and fantastical subjects.

As with Ottoman paintings, Safavid manuscript illustrations provide insight into the use of carpets at court. In this illustration from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, a ruler is depicted seated atop a small but luxurious carpet in an outdoor pleasure pavilion. Court carpets would be used for outdoor gatherings like this, as well as within the palaces of the Safavid shahs.

Copyright: Kendra Weisbin, “Introduction to the court carpets of the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal empires,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-the-court-carpets-of-the-ottoman-safavid-and-mughal-empires/.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/F99w4VEAsHI?si=o2WOrVJ3yUuvy3v0

Copyright: Dr. Ariel Fein and Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “Ottoman prayer carpet with triple-arch design,” in Smarthistory, October 11, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/ottoman-prayer-carpet-with-triple-arch-design/.

Ceramic Tiles (Iznik)

Video URL: https://youtu.be/_BRNHPiu-OM?si=RZKQla44WnmrYTVU

Copyright: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Beth Harris, “Topkapı Palace tiles,” in Smarthistory, June 3, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/topkapi-palace-tiles/.

Portrait of Hurrem Sultan/Roxelana

Suleiman I defied tradition to marry Hurrem, a young woman from Ruthenia (now western Ukraine) who had been captured and enslaved by Crimean Tatars. While a captive, Hurrem was eventually taken to Istanbul and purchased by Suleiman’s mother as a gift for her son. As Hurrem Sultan, she became one of the most important and influential women in Ottoman history, setting a precedent for the powerful wives and chief concubines who followed her in what became known as the Sultanate of Women

The wife or mother of the reigning sultan had unequaled power over the imperial family and frequently gained popularity by funding public monuments and buildings for use by the public, including soup kitchens, bath houses, fountains, and schools. Many of these were vaqfs, charitable endowments intended to help the poor or to serve religious purposes. Wealthy women (and men as well) often donated land or buildings along with funds to assist the public.

Outsiders who sought favor often wrote letters to or sent female relatives to plead their case with the sultan’s wife or mother. She in turn might transform her popular influence into political power by conspiring with palace administrators like the palace’s chief eunuch, becoming one of the most powerful people in the empire. The chief wife and the sultan’s mother were often rivals for political prominence; clashes could occur between them and also with the sultan’s chief (male) advisers at court. The Sultanate of Women lasted more than a century, ending in the late seventeenth century when a number of sultans died unexpectedly in a short period. The result was instability in the palace and a weakening of the interpersonal relationships between the imperial family and outside advisers upon whom the Sultanate of Women had relied.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). The Safavid Empire. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.