26 WESTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid period started with a revolution. Caliphs of the earlier Umayyad dynasty had ruled for almost a hundred years after they assumed power in 661 (after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 C.E.), and over this time discontent gradually built up against them, both from rival elites and from large sections of the general population. After three years of open fighting the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, was assassinated in 750. This is when the Abbasid caliphate began.With the Abbasids’ take over of the caliphate, the center of power of the Islamic world shifted to Iraq and Khurasan (where the Abbasid movement had originated). In order to remove themselves from what had been the center of Umayyad power—Damascus, and Greater Syria more broadly—the Abbasids established a new capital in Baghdad in 762, built as a round city with the palace at its center.

Artistic production shifted in this period, with new modes of production that moved away from the late antique aesthetics typical of the Umayyads. Trade played an important role in the development of Islamic art in this period—for instance, ceramics imported from Tang China inspired so-called splash ware produced in Iraq. Sea trade was crucial for the exchange with China, and direct evidence for it exists, for instance, in the Belitung shipwreck, the remains of a ship that sank in the 830s with a cargo of Tang ceramics shipped from China to West Asia.

The Umayyads declared themselves caliphs in 929, in direct rivalry with the Abbasids, who held the caliphate since 750, and were centered in present-day Iraq. In the early 10th century, the Fatimids, a Shi’ite dynasty that emerged from present-day Tunisia, conquered Egypt in 969 and made its new capital there, and also claimed the title of caliph. While direct conflict at times emerged between the Abbasids and Fatimids, especially as the Fatimids sought to expand their rule into Syria, the Umayyads did not seek to expand beyond their lands in the Maghrib. The Umayyad caliphate fell among succession struggles in 1031, and was succeeded by the so-called Taifa kingdoms, local dynasties centered in cities such as Zaragoza, Málaga, and Granada.

The artistic legacies of the Abbasid caliphate are varied. Some of the monuments described in this essay were short lived; impressive as they were, the palaces of Samarra barely lasted for two generations. But many visual and technological innovations of the period, from lusterware ceramics to “Kufic” script to the engagement with classical scientific literature, continued to be significant components of Islamic culture—and influences on surrounding cultures—for centuries to come.

Copyright: Dr. Beatrice Leal, “Arts of the Abbasid Caliphate,” in Smarthistory, December 19, 2021, accessed May 2, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/arts-abbasid-caliphate/.

Copyright: Dr. Patricia Blessing, “Islamic art c. 900–1400,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, March 25, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/islamic-art-c-900-1400/.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Islamic Philosophy

The rise of Islam is linked to the decline of the Roman and Persian Empires. More specifically, the ruinous wars that the two once-great powers fought left both weak. In 622 CE, the Prophet Muhammed led his followers out of Mecca to Medina, which signaled the birth of Islam as a political power (Adamson 2016, 20). In the early years of Islam, theologians prohibited the teaching of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers on the grounds that they were contrary to the true Muslim faith. This restriction began to give way in the eighth century CE, which led to the flourishing of philosophy in the Islamic world.

As the Roman Empire declined, the Muslim world safeguarded ancient philosophical Greek and Latin texts through major centers of learning in Alexandria, Baghdad, and Cordova. Islamic philosophers published major works in metaphysics, epistemology, and natural philosophy. Key Islamic scholars who carried classical philosophy forward include Ibn Sina (whose Latin name became Avicenna), Ibn Rushd (whose name was Latinized to Averroes), and Al-Gazali. Of these three, Ibn Sina is the linchpin of Muslim philosophy. His genius inaugurates the shift from an early period focused on the consolidation of Greek learning to a later period of philosophical and scientific innovation (Adamson 2016).

Ibn Sina (Avicenna)

Abū-ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn-ʿAbdallāh Ibn-Sīnā (c. 970–1037 CE) was a Persian polymath who published works in philosophy, medicine, astronomy, alchemy, geography, mathematics, Islamic theology, and even poetry. Because of the vast scope of Ibn Sina’s intellectual endeavors, he is considered the linchpin between Islamic philosophy’s formative phase and its more creative phase during the Golden Age of Islam, which extends from roughly the 8th through the 13th centuries. During this period, Islamic culture and learning flourished, and the Muslim-ruled lands spread from the Middle East, through Northern Africa, and into the Iberian Peninsula. Taking his cue from Aristotle, Ibn Sina sought to present a complete philosophy that would address both theoretical and practical philosophy. Some have estimated that Ibn Sina published as many as 450 works, though others place the figure at under 100 (Namazi 2001).

Ibn Sina’s work was highly influential within both the Muslim and the Christian world. His proof of the existence of God became predominant. Called the Proof of the Truthful, the argument proposed that existence requires that there be a necessary entity—an entity that cannot not exist. Elements of the material world—animals, plants, rivers, mountains—are contingent—that is, they come and go. They may have existed in the past but do not exist now, or they may exist now but will not exist in the future. Therefore, they can not exist. Therefore, there must be a nonmaterial entity that causes this material world to come into existence.

Much like Aristotle, Ibn Sina believed that the rational order of the universe was comprehensible by our human minds, and his well-ordered and complete philosophical project demonstrated this (Gutas 2016). Ibn Sina’s most influential book is the Canon, a five-volume medical encyclopedia that—translated into Latin and Hebrew—became the textbook for the study of medicine in European universities from the 12th to the 17th century (Amr and Tbakhi 2007). Ibn Sina’s epistemology—and in particular, his development of an empiricism that advances far beyond the Epicureans and is, in fact, comparable to that of John Locke—has received less attention.

Ibn Sina, similar to Locke, proposed that humans are born with a rational soul that is a blank slate. The child possesses the five external senses associated with the animal soul (sight, smell, sound, taste, and touch) and two internal senses of the human rational soul, memory and imagination. The child gathers and stores information from the senses and is able to abstract intelligible concepts about the world from this sensual data and about the human soul (rationality) through reflection (which Locke later calls experience). So, a child in a high chair might drop food and observe that it falls to the floor, based on experience, but a child through reflection also observes a causal relationship. For Ibn Sina, gravity exists both in the materialist realm of the senses and in the cognitive realm of the mind or soul. Like gravity, numbers exist in both realms, the abstract concept of the number two and concrete pairs of objects, such as two shoes or two apples. He explains in The Metaphysics of Healing, “Number has an existence in things and an existence in the soul” (quoted in Tahiri 2016, 41).

The child’s mind organizes this information—making generalizations, separating out the essential from the nonessential, and affirming or negating relationships. Through this process, the child forms definitions and propositions that reflect the logical and mathematical modes of rational thought (Gutas 2012).

Ibn Sina stated that all knowledge is a result either of forming concepts or acknowledging the truth of propositions. He distinguished different types of propositions, each of which have different sources and therefore different ways to prove or disprove the proposition. Table 4.2 lists 5 of Ibn Sina’s 16 types of propositions and examples (Gutas 2012).

| Type of Proposition | Example |

|---|---|

| Sense data | Grass is green. |

| Data of reflection | Humans think. |

| Tested data | Fire burns flesh. |

| Propositions with a middled term | Six is an even number. |

| Data provided by multiple reports | The US Constitution was written in 1787. |

Some types of propositions, such as sense data and data based on reflection, are knowledge based on the external or internal senses. Tested data, however, can be accepted as true only after repeated observation and attribution to a cause. For example, “fire causes burns” would be based on the observations that fire is hot, hot things burn objects (cause), and flesh is an object. The truth of data provided by multiple reports can only be confirmed if it has been reported by so many sources that it is highly unlikely to be a falsehood.

Building on Aristotle’s idea of induction conveyed in Posterior Analytics, Ibn Sina developed a scientific methodology of experimentation in his treatise “On Demonstration” within his Book of Healing. Induction involves making an inference based on observations. Ibn Sina stated that—unlike untested induction—experimentation provides the basis of certain knowledge. He used the example of the relationship between consuming the plant scammony and purging (vomiting). He noted that the observation of a positive correlation does not prove that the relationship exists but rather that the lack of observation of a negative correlation (cases in which scammony did not cause purging) provides stronger evidence. Ibn Sina’s experimentation involved a search for falsification of a correlation—just like the scientific method used today, which, for example incorporates control groups (McGinnis 2003). Furthermore, Ibn Sina insisted that a causal term be inserted into the relationship that is observed. It is not scammony that causes purging but a property that scammony has that requires further investigation. So Ibn Sina’s argument is (1) scammony has the power to purge, (2) scammony causes purging, (3) a power to purge causes purging. Exactly what the power to purge is remains uncertain until further investigation. In the first example above, the cause is established: (1) fire burns flesh, (2) fire is hot, (3) heat burns flesh.

As advancement of experimental knowledge challenged Islamic theology, debate emerged over how to reconcile faith and science.

Ibn Rushd (Averroes)

Ibn Rushd (1126–1198), known as Averroes in the Latin world, was born into a family of jurists in Cordova in Andalusia, or Muslim-ruled Spain. Like Ibn Sina, his philosophy took its inspiration from Aristotle. Like Ibn Sina and Aristotle, his work ranged across a number of domains, from metaphysics and logic through medicine and natural philosophy. Much of this work took the form of commentaries on Aristotle. He thought that the Neoplatonic interpretation of Aristotle had distorted the original meaning of Aristotle’s work and sought a return to Aristotle’s original works in his commentaries. Ibn Rushd was pivotal to the revival of Aristotle in Europe. The tradition of commentary on Aristotle’s works that developed among Islamic philosophers developed Aristotle’s thought in fascinating ways and kept Aristotle scholarship alive.

Ibn Rushd saw demonstration as the key to logic and the condition for philosophical certainty and scientific reasoning (Ben Ahmed and Pasnau 2021). This had important theological implications and led to confrontations with theologians who believed that philosophical reflection was at odds with the Muslim faith. He sought to demonstrate the existence of God by showing that his creation was fine-tuned for humans in a way that could not be simply a matter of chance. In addition, he advanced an argument, taken up today by intelligent design advocates, that holds that it is not possible to explain the complexity of living beings without a creator.

Even as philosophy gained ground in the Islamic world, theological traditionalists remained influential. These traditionalists denied that reason could bring one closer to God. Ibn Rushd was among a number of philosophers who opposed this traditionalism and sought to show the compatibility of faith and reason. Not only did Ibn Rushd seek to show that reason was compatible with faith, he went further and cited Quranic scripture to show that religion required philosophical reflection. He wrote, “Many Quranic verses, such as ‘Reflect, you have a vision’ (59.2) and ‘they give thought to the creation of heaven and earth’ (3:191), command human intellectual reflection upon God and his creation” (quoted in Hiller 2016).

Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers

Al-Ghazali (c.1056–1111) was one of the most prominent Sunni Muslim theologians and philosophers. Writing in a period after the initial establishment of the Sunni sect, he sought to refute various challenges to its teachings from both Shi’ite religious scholars and philosophers. In his most well-known work, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, Al-Ghazali sought to refute these challenges while also strengthening the theological basis for Sunnism. Ibn Rushd wrote a refutation of Al-Ghazali’s The Incoherence of the Philosophers. In it, he argues against Al-Ghazali’s claim that philosophical reflection must remain distinct from the Muslim faith and that mystical union with Allah or God is the only true path to religious enlightenment. This dispute between Al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd represents the conflict between faith and reason that characterized medieval Islam. This same conflict remains relevant in the present.

LITERATURE

The Rose Garden of Sa’di (translated by L. Cranmer-Byng and S. A. Kapadia)

Musharrif al-Dīn ibn Muṣlih al-Dīn, known as Sa’di or Saadi, wrote both poetry and prose in Persian. The Rose Garden is a combination of the two genres: mostly prose, with poems and lines of poetry scattered throughout. The stories and anecdotes in The Rose Garden offer examples of wisdom drawn from history and literature. Sa’di clearly admired Sufis, and he devotes a section of the work to “The Wisdom of Dervishes”; in it, the Sufi dervishes challenge rulers to behave morally, unafraid of earthly consequences. There are examples of rulers who are driven from power because of their cruelty, greed, or even stupidity. In other anecdotes, people are advised to avoid conflict when possible: suggesting, in one famous example, that a kind lie sometimes might be better than a harmful truth.

Chapter II: The Morals of Dervishes

Fault-Finding and Self-Conceit

I remember being pious in my youth, given to night vigils, prayers, and abstinence. One night I was sitting with my father, on whom God have mercy, keeping awake and holding the precious Koran in my lap, whilst the company around us slept. I said: “Of these people not one lifts up the head or bows the knee (in prayer). They are all sound asleep, as though they were dead.” He answered: “Little one of thy father, would that thou wert also asleep, rather than proclaiming the faults of others.”

Verses

The braggart sees himself alone,

Since he is veiled in self-conceit;

Were God’s all-seeing eye his own,

He would no weaker braggart meet.

Forbearance

A band of vagabonds meeting a Dervish spoke evilly to him, beat him and ill-used him, where- upon he brought his complaint to his superior. The Director replied: “My son! the patched gown of the Dervishes is the garb of resignation, and he who, wearing it, cannot bear with injury, is but a pretender to whom our garb is forbidden.”

Distich

Thou canst not stir the river’s bed with stones:

Wisdom aggrieved is but’a shallow brook.

Verses

If any injure thee, thy spleen control,

Since by forgiveness thou shalt cleanse thy soul.

O brother, since the end of all is dust,

Be dust, ere unto dust return thou must.

Humility

Hark to my tale, how once a quarrel rose

Betwixt a flag and curtain in Bagdad,—

How, drooping from the march, the dusty flag Reproached the curtain: “Art not thou and I

Both servants in the Sultan’s court? I know

No respite from his service. From the light

Of cock-crow to the gloom of nightingales

I travel, travel: thou hast neither siege

Nor battle to endure, nor whirling sand,

Nor wind, nor heat to suffer; while my step

Is ever on the march. Why art thou held

More honoured? Thou art cherished by slim boys

Of moon-pale beauty, jasmine-scented maids

Touch thee caressingly; while I am rolled

By raw recruits, and ofttimes on the trail

Carried head downwards.”

Then the curtain spake:

“My head is humbly on the threshold laid,

Unlike thine own, that flaunting would defy

The golden-armoured sun. Whoever rears

The neck of exaltation shall descend

Most speedily neck level with the dust.”

The Dervish Way

The way of dervishes is gratefulness, praise,

worship, obedience, contentment, and charity,

believing in the unity of God, faith, submission,

and patience. Whoever hath these qualities is

indeed a Dervish, though he may wear fine

raiment; whereas the idler, who neglecteth

prayer, who goeth after ease and pleasure, turneth

day into night in the bondage of desire, and night

into day in the slumber of forgetfulness, eateth

whatever he layeth hold on, and speaketh that

which is uppermost, he is an evil-doer, though

he may wear the garb of the Dervishes.

Verses

Thou who within of good resolve art bare,

Yet dost the mantle of the righteous wear;

Thou who hast but a reed-mat to thy floor,

Hang not the rainbow-curtain on the door.

Chapter III: The Preciousness of Contentment

Wisdom and Worldly Power

Two sons of princes lived in Egypt, the one given to the study of science, the other heaping up riches, till the former became the wise man of the age, and the latter the King of Egypt. Then the rich man looked with the eye of scorn upon the philosopher, and said: “I have reached the sovereign power whilst thou remainest poor as before.” He replied: “O brother! I must needs be grateful to the Most High Creator, that I have found the inheritance of the prophets, while thou hast obtained the inheritance of Pharaoh and Haman —the Kingdom of Egypt.”

Mesnevi

I am that ant which under foot is trod.

No wasp am I, for man to curse my sting.

How can I rightly thank Almighty God

That I am harmless both to clown and king?

Frugality

It is written in the annals of Ardeshir Babekan that he asked an Arabian physician how much food ought to be taken daily. He answered: “The weight of one hundred dirrhems were enough.” The king asked him: “What strength will this quantity give me?” He replied: “This quantity will carry thee; but whatever’ more is taken, thou wilt be the carrier of it.” Eat to live, thy prayers repeating; Think not life was made for eating.

Self-Dependence

They asked of Hâtim Tai if he had seen any one in the world of nobler sentiments than himself. He replied: “Yes, one day I slew forty camels to give a banquet to Arab chieftains. I went forth upon some affair to a corner of the desert, where I saw a gatherer of sticks, who had piled up a heap of brushwood. I asked him why he had not become a guest of Hâtim, seeing that many people had gathered around his carpet. But he replied: ‘He that hath bread procured by honest sweat, To Hâtim will not bear to be in debt.’ Then I perceived that his sentiments were nobler than mine own.”

Pearls and Starvation

I saw an Arab sitting amid a circle of jewelers at Bosrah, and telling them tales. He said: “Once I lost my way in the desert, and had consumed all my provisions. I was prepared to die, when suddenly I beheld a bag of pearls. Never shall I forget the joy I felt, deeming them to be parched grain, nor the bitterness and despair with which I found them to be pearls.”

Verses

In deserts, amid shifting sand and drouth,

Nor pearl nor shell is manna to the mouth.

Ah! what avails, when food and strength are gone,

The girdle with its pearls or pebbles strown?

World Literature I: Beginnings to 1650 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Rumi

Selections from the Persian Mystics Jalálu’d-Dín Rúmí, edited by F. Hadland Davis, L. Cranmer-Byng, and S. A. Kapadia

Although Rumi was born in Afghanistan and lived in Turkey, his poetry was written mostly in Persian, and his Sufi religious beliefs transcended national boundaries.

Afghanistan was on the edge of the Persian Empire, and Rumi’s father was a traditional Islamic religious teacher who trained his son to follow in his footsteps.

When he was forty, Rumi had a religious epiphany when he met Shams, a wandering Sufi, who was about sixty. Rumi became a Sufi, and the outpouring of poetry that followed was staggering. Sufism combines ideas from Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism, and it attempts to achieve union with God: not by logical means (which is beyond the ability of the human mind), but by emotional means. Rumi founded the Mevlevi order of dervishes, sometimes called whirling dervishes because of the spinning dance that they do to achieve a trance-like state. Despite the loss of Shams, who may have been murdered by Rumi’s jealous disciples, Rumi continued to write, amassing over forty thousand couplets of poetry over his lifetime. The Divani Shamsi Tabriz is a collection of individual poems, including poems in the ghazal form and the rubaiyat form (which are different ways to group couplets). The Masnavi (also spelled Mathnavi or Mathnawi) is referred to as the “Quran in Persian”; it was meant to teach his followers the spirit of Sufi Islam, drawing on the Quran, folktales, and anecdotes (among other forms) for the prose sections between the poems. Unlike the Divani Shamsi Tabriz, the Masnavi is a cohesive collection, with a moral to each story. Today Rumi is the most important medieval Persian poet and one of the most widely-read mystical poets.

Sorrow Quenched In The Beloved

Through grief my days are as labour and sorrow.

My days move on, hand in hand with anguish.

Yet, though my days vanish thus, ‘tis no matter.

Do Thou abide, Incomparable Pure One.

The Music Of Love

Hail to thee, then, O love, sweet madness!

Thou who healest all our infirmities!

Who art the Physician of our pride and self-conceit!

Who art our Plato and our Galen!

Love exalts our earthly bodies to heaven,

And makes the very hills to dance with joy!

O lover, ‘twas Love that gave life to Mount Sinai,

When “it quaked, and Moses fell down in a swoon.”

Did my Beloved only touch me with His lips,

I too, like a flute, would burst out into melody.

When The Rose Has Faded

When the rose has faded and the garden is withered,

The song of the nightingale is no longer to be heard.

The BELOVED is all in all, the lover only veils Him;

The BELOVED is all that lives, the lover a dead thing.

When the lover feels no longer love’s quickening,

He becomes like a bird who has lost its wings. Alas!

How can I retain my senses about me,

When the beloved shows not the Light of His countenance?

The Silence Of Love

Love is the astrolabe of God’s mysteries.

A lover may hanker after this love or that love,

But at the last he is drawn to the king of Love.

However much we describe and explain Love,

When we fall in love we are ashamed of our words.

Explanation by the tongue makes most things clear,

But Love unexplained is better.

Earthly Love Essential To The Love Divine

In one ‘twas said, “Leave power and weakness alone;

Whatever withdraws thine eyes from God is an idol.”

In one ‘twas said, “Quench not thy earthy torch,

That it may be a light to lighten mankind.

If thou neglectest regard and care for it,

Thou wilt quench at midnight the lamp of Union.”

The Eternal Spendour Of The Beloved

Why dost Thou flee from the cries of us on earth?

Why pourest Thou sorrow on the heart of the sorrowful?

O Thou who, as each new morn dawns from the east,

Art seen uprising anew, like a bright fountain!

What excuse makest Thou for Thy witcheries?

O Thou whose lips are sweeter than sugar.

Thou that ever renewest the life of this old world.

Hear the cry of this lifeless body and heart!

Woman

Woman is a ray of God, not a mere mistress,

The Creator’s Self, as it were, not a mere creature!

The Divine Union

Mustafa became beside himself at that sweet call,

His prayer failed on “the night of the early morning halt.”

He lifted not head from that blissful sleep,

So that his morning prayer was put off till noon.

On that, his wedding night, in the presence of his bride.

His pure soul attained to kiss her hands.

Love and mistress are both veiled and hidden.

Impute it not a fault if I call Him “Bride.”

Copyright: World Literature I: Beginnings to 1650 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

ARCHITECTURE

The Great Mosque (or Masjid-e Jameh) of Isfahan

Most cities with sizable Muslim populations possess a primary congregational mosque. Diverse in design and dimensions, they can illustrate the style of the period or geographic region, the choices of the patron, and the expertise of the architect. Congregational mosques are often expanded in conjunction with the growth and needs of the umma, or Muslim community; however, it is uncommon for such expansion and modification to continue over a span of a thousand years. The Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran is unique in this regard and thus enjoys a special place in the history of Islamic architecture. Its present configuration is the sum of building and decorating activities carried out from the 8th through the 20th centuries. It is an architectural documentary, visually embodying the political exigencies and aesthetic tastes of the great Islamic empires of Persia. Another distinctive aspect of the mosque is its urban integration. Positioned at the center of the old city, the mosque shares walls with other buildings abutting its perimeter. Due to its immense size and its numerous entrances (all except one inaccessible now), it formed a pedestrian hub, connecting the arterial network of paths crisscrossing the city. Far from being an insular sacred monument, the mosque facilitated public mobility and commercial activity, thus transcending its principal function as a place for prayer alone.

Courtyard, The Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: AlGraChe, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The mosque’s core structure dates primarily from the 11th century, when the Seljuq Turks established Isfahan as their capital. Additions and alterations were made during Il-Khanid, Timurid, Safavid, and Qajar rule. An earlier mosque with a single inner courtyard already existed in the current location. Under the reign of Malik Shah I and his immediate successors, the mosque grew to its current four-iwan design. Indeed, the Great Mosque of Isfahan is considered the prototype for future four-iwan mosques. Linking the four iwans at the center is a large courtyard open to the air, which provides a tranquil space from the hustle and bustle of the city. Brick piers and columns support the roofing system and allow prayer halls to extend away from this central courtyard on each side. Aerial photographs of the building provide an interesting view; the mosque’s roof has the appearance of “bubble wrap” formed through the panoply of unusual but charming domes crowning its hypostyle interior.

Dome with oculus in the hypostyle prayer hall, Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This simplicity of the earth-colored exterior belies the complexity of its internal decor. Dome soffits (undersides) are crafted in varied geometric designs and often include an oculus, a circular opening to the sky. Vaults, sometimes ribbed, offer lighting and ventilation to an otherwise dark space. Creative arrangement of bricks, intricate motifs in stucco, and sumptuous tile-work (later additions) harmonize the interior while simultaneously delighting the viewer at every turn. In this manner, movement within the mosque becomes a journey of discovery and a stroll across time.

Given its sprawling expanse, one can imagine how difficult it would be to locate the correct direction for prayer. The qibla iwan on the southern side of the courtyard solves this conundrum. It is the only one flanked by two cylindrical minarets and also serves as the entrance to one of two large, domed chambers within the mosque.

Muqarnas, south iwan of the Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: youngrobv, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Similar to its three counterparts, this iwan sports colorful tile decoration and muqarnas or traditional Islamic cusped niches. The domed interior was reserved for the use of the ruler and gives access to the main mihrab of the mosque.

Interior decoration of Taj-al-Mulk (north) dome (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The second domed room lies on a longitudinal axis right across the double-arcaded courtyard. This opposite placement and varied decoration underscore the political enmity between the respective patrons; each dome vies for primacy through its position and architectural articulation. Nizam al-Mulk, vizier to Malik Shah I, commissioned the qibla dome in 1086. But a year later, he fell out of favor with the ruler and Taj al-Mulk, his nemesis, with support from female members of the court, quickly replaced him. The new vizier’s dome, built in 1088, is smaller but considered a masterpiece of proportions.

When Shah Abbas I, a Safavid dynasty ruler, decided to move the capital of his empire from Qazvin to Isfahan in the late 16th century, he crafted a completely new imperial and mercantile center away from the old Seljuq city. While the new square and its adjoining buildings, renowned for their exquisite decorations, renewed Isfahan’s prestige among the early modern cities of the world, the significance of the Seljuq mosque and its influence on the population was not forgotten. This link amongst the political, commercial, social, and religious activities is nowhere more emphasized than in the architectural layout of Isfahan’s covered bazaar. Its massive brick vaulting and lengthy, sinuous route connects the Safavid center to the city’s ancient heart, the Great Mosque of Isfahan.

Copyright: Dr. Radha Dalal, “The Great Mosque (or Masjid-e Jameh) of Isfahan,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed May 2, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-great-mosque-or-masjid-e-jameh-of-isfahan/.

Samarra

The wall surrounding the Great Mosque of Mutawakkil, Samarra, with its spiral minaret in the background (photo: Taisir Mahdi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The plans of Samarra’s palaces, mosques, mansions, and gardens reflect the Abbasid empire’s enormous wealth and resources. New palace complexes of unprecedented sizes were built, vastly larger than the palaces of their predecessors, the Umayyad caliphs, and (perhaps of even more importance to their patrons), equal or larger than those of their rivals in Constantinople, the Byzantine emperors. Their designs utilized horizontal scale, as well as axiality and symmetry to make a visual impact. They often contain repetitions of elements like gateways, iwans, and halls whose practical function was to produce a sense of incomprehensible vastness and harmonious order.

The plan of the Balkuwara Palace, for example, leads the visitor through three courtyards, each preceded by a monumental gate, culminating in a grand iwan that in turn opens onto a cross-shaped hall made of four smaller iwans around a dome. The sequence of gate, courtyard, iwan, and dome is familiar from earlier Islamic palaces, but here the courtyard is tripled, and there are four iwans (rather than the more traditional single structure) beneath the final dome. The repetition of large open spaces conveyed a sense of monumentality without focusing attention on any one element of the building—and without depending on expensive materials such as marble.

In the Balkuwara, the materials become finer as one moves closer to the heart of the complex—the great iwan opening onto the third courtyard. The outermost retaining walls and the walls of the first and second courtyard were built of pisé (rammed earth), the first and second gates were made of unfired mud brick, and the third gate, courtyard, great iwan, and all surrounding rooms were made of fired brick. This selective use of finer, more durable materials in the areas of greatest significance enabled the vast scale of these buildings. It also suggests the Abbasid caliphs preferred larger palace complexes to smaller but more permanent ones.

Samarra’s congregational mosques are also breathtakingly large. The Great Mosque of Mutawakkil (at 37,440 square meters) is over twice the area of the Great Mosque of Damascus (15,642 square meters) built by the Umayyads. The Great Mosque of Mutawakkil was surrounded by an exterior enclosure, known as a ziyada. The ziyada included a dar al-imara (a small palace used by the caliphs or their representatives to prepare for Friday prayer) and the famous freestanding minaret that towered 50 meters above the mosque.

The Abbasid period was an era of intellectual and technological advancement, fueled by the wealth of the caliphate and the resulting magnetic pull that Baghdad and other cities exerted on scholars, artisans, and artists. The artistic achievements of the period are evident in Samarra’s architecture, especially in the ornamentation of interior spaces.

Floral pattern with geometric designs, grapes, vines, and ears of pine cones, 3rd century AH (9th century C.E.), carved stucco, Herzfeld’s Style II (Second Style), Samarra, Iraq (Iraq Museum, Baghdad; photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0)

Samarra is particularly famous for its carved stucco ornament, which adorned dadoes (the lower half of walls). Ernst Herzfeld, who excavated the site between 1910 and 1913, identified three distinct styles of carving in the stucco dadoes: (1) geometric fields filled with repeating vine leaves arranged in rows; (2) a wider variety of vegetal forms rendered in a flat manner and surrounded by more complex geometric frames; and (3) sinuous, spiraling lines combined to form highly abstract vegetal motifs. Herzfeld called this last style the “First Style” because it was so prevalent at the site; it is also known as the Beveled Style due to the sloping edges of the incised lines.

Panel in the Beveled Style, Samarra, stucco (Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin; photo: Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The abstract and repetitive nature of these carving styles may be partially due to the costs of the massive building projects. In addition to the economic efficiency of repeating patterns, these styles are well suited to the large spaces that define Samarra’s buildings. They are most stunning, and the rhythms of the flat, textile-like patterns are clearest, when seen from a distance. This ornament, which conveys a sense of harmonious order, is exploited most powerfully in the palaces where patterns sometimes repeat across multiple spaces. In the Dar al-Khilafa (the imperial palace), just four patterns were used to decorate a dozen rooms around the four audience iwans. The iwans themselves were decorated with marble revetments, also featuring the same four patterns.

Samarra’s private houses also used symmetry in their design. Like the palaces they were designed around courtyards; sometimes two iwans would face each other across a single courtyard. The houses also featured extensive and exuberant stucco dadoes in the same styles. In these residences, repetition of patterns seems less important. In one of the houses excavated by Herzfeld, over a dozen surface patterns were recorded in as many rooms, suggesting a different approach taken in smaller, more informal spaces.

Minaret, Mosque of Ibn Tulun, completed 878/79, Cairo, Egypt (photo: youssef_alam, CC BY 3.0)

Copyright: Dr. Matt Saba, “Samarra, a palatial city,” in Smarthistory, May 4, 2022, accessed May 6, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/samarra/.

PERFORMING ARTS

VISUAL ARTS

Iranian Ceramics

Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the center of this 12th-century ceramic bowl we see two beautifully dressed figures sitting on a throne or takht. They are surrounded by four additional figures, one on either side, and two behind the throne. They tilt their heads, appearing to listen intently to the man sitting opposite them, who gestures forward as if in mid-speech. This figure is reciting poetry. They appear in a peaceful outdoor setting, where we see fish swimming in a pond and birds gathering at their feet and flying overhead.

We are looking at a depiction of a majlis, a gathering of members of the royal court and intellectuals for the public recitation of poetry. The artist paid attention to small details to give life to the motif. The figure seated on the throne closest to us is distinguished from the rest by a distinctive headdress, perhaps a crown. He raises his hand as if responding to the skillful recitation performed by the figure opposite. The courtier to the left of the takht appears to rest his body on the throne, rapt by the poetic performance.

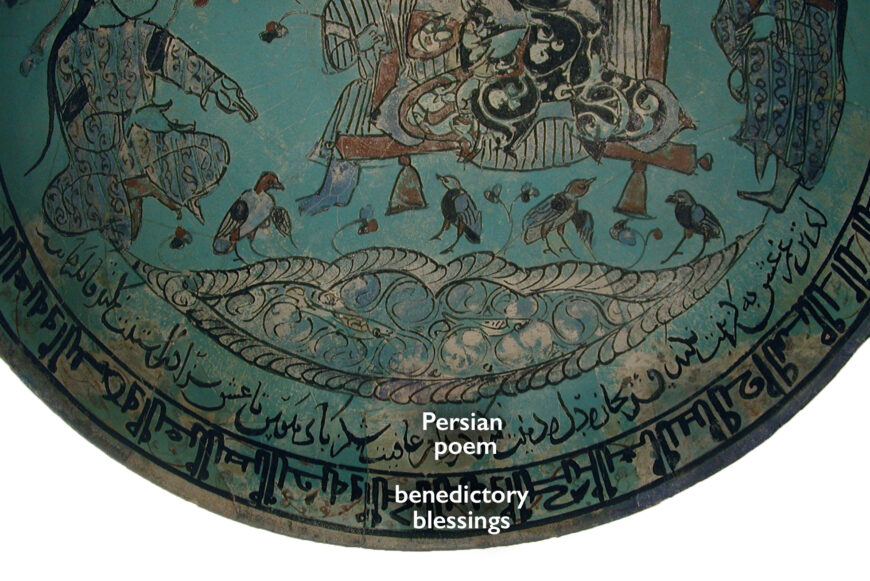

Poetry is central to this bowl—Persian and Arabic poems encircle the vessel on both its exterior and interior. Interestingly, at least one of the poems adorning its surface was composed by Abu Zayd who also made and decorated this bowl. Abu Zayd is regarded today as perhaps the most famous potter of medieval Iran. Signed and dated to 1186 C.E., this bowl is Abu Zayd’s earliest known work, and already represents his accomplishments in his craft.

Examples of minaʾi and lusterware, 12th–13th century. From left: Minaʾi bowl with enthroned ruler, 13th century, Kashan, Iran (Victoria & Albert Museum); Abu Zayd, Star tile with prince on horseback, 1211 C.E., fritware with luster decoration, 27.5 x 26.5 x 1.5 cm, Kashan, Iran (Museum of Fine Arts Boston); Abu Zayd, lusterware plate with mystical allegory of the quest for the Divine, 1210 C.E., stonepaste painted overglaze with luster, 35.2 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (National Museum of Asian Art); jar with hunters, 12th–13th century, stonepaste with minaʾi decoration, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

New ceramic technologies and experimenting with glazes: minaʾi and luster

Abu Zayd’s bowl is made with a new ceramic technology called stonepaste. The development of stonepaste in the tenth and early eleventh centuries shaped ceramic production across Egypt and Central Asia. Although it was neither expensive nor luxurious, the advantage of stonepaste was that it could be fashioned into thin walled ceramics, which evoked the highly valued porcelain vessels imported from China. This new medium triggered experimentation with inventive shapes, including functional vessels, tiles, and figural sculpture, as well as new decorative approaches. [1]

Abu Zayd’s stonepaste bowl has a turquoise underglaze and polychrome decoration in the minaʾi technique—one of the most up to date ceramic techniques of his time. Vessels produced with mina’i painting involved applying decoration—in this case color, and occasionally gilding—to an already finished (fired and glazed) product. Minaʾi wares were produced over a white or turquoise glazed base and fully decorated with detailed figural paintings of courtly life, including musicians, dancers, and hunting, as well as narrative scenes and astrological motifs. Minaʾi ware were widely sought after and eventually produced on an industrial scale for a range of patrons, from individuals purchasing in the open market to commissions produced for elite members of the ruler’s court. However, the production of mina’i ware was short lived, lasting only through the early thirteenth century, when they were eclipsed by lusterware, another popular ceramic form. Lusterware became one of the most prized ceramic types associated with the luxury arts, and were widely produced and traded across the Islamic world and later across western Europe. Abu Zayd contributed to the refinement of both of these techniques, producing some of the most complex examples of these glazes.

Interior inscriptions, Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Around the rim of the bowl is yet another inscription, benedictory blessings, or good wishes such as “eternal glory, happiness, victory, and grace,” written in kufic script. [3] Some benedictory inscriptions were addressed directly to the owner, further suggesting that these inscriptions (as well as the poetry) were meant to be read aloud by their owners. In this bowl, Abu Zayd concluded his signature on the exterior of the bowl, writing “long life to its owner and to its writer,” thus invoking the owner of the vessel. Text and image combine together to enliven the majlis scene and engage the viewer in recitation.

Persian poem followed by Abu Zayd’s signature, Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E., stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter, Kashan, Iran (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Abu Zayd emphasizes his authorship as going hand in hand with his skills in the ceramic industry. Not only does he claim the oral poem, by calling himself the reciter, but he also takes ownership of its written manifestation on the bowl by describing himself as the writer. In this case, these roles appear to take precedence over the ceramic craft, which is only referred to once. However, on other vessels, Abu Zayd specifies that he made and decorated the work, claiming artistic ownership as well as giving us insight into the division of labor in the ceramic industry. Abu Zayd’s ceramics reveal the distinctive combination of literary and visual worlds in 12th-century Iranian ceramics.

While not every ceramicist was a poet like Abu Zayd, it is possible that many ceramicists themselves engaged in the sophisticated literary culture of the time. With so many ceramic objects inscribed with poetic quatrains and other verses, it seems likely that the verses themselves were recited aloud in the ceramic workshop from an anthology by one ceramicist while another inscribed them on the vessels. [4]

Abu Zayd died some time after 1220, but his poetry continued to be invoked into the late 13th century. Like so many of the poems he inscribed on his own vessels, his poems eventually became divorced from his name, but were remembered orally and repeated without attribution on luster-painted bowls and tiles well into the late 13th century. [5] As an artist, scribe, and poet, Abu Zayd and his ceramics left an indelible impact on the literary and visual arts of Iran in the 12th century and beyond.

Copyright: Dr. Ariel Fein, “Artist, scribe, and poet: Abu Zayd and 12th-century Iranian ceramics,” in Smarthistory, May 3, 2023, accessed May 6, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/artist-scribe-and-poet-abu-zayd-and-12th-century-iranian-ceramics/.

Two Royal Figures

Video URL: https://youtu.be/4S9Bqo_LX7k?si=KnInKKElv2O72oeW

Copyright: Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Two Royal Figures,” in Smarthistory, December 5, 2015, accessed May 6, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/two-royal-figures-saljuq-period/.