5 WESTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

Introduction – Cradle of Civilization

Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization by DR. SENTA GERMAN

Home to some of the earliest and greatest empires, the Near East is often referred to as the cradle of civilization.

Map of the ancient Near East (underlying map © Google)

Some of the earliest complex urban centers can be found in Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (early cities also arose in the Indus Valley and ancient China). The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed “the near east.” Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn’t have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West’s interests in the Biblical “Holy Land” that ancient Near Eastern materials have been be regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art. An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French 19th century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were discovered and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The history of the Ancient Near East is complex and the names of rulers and locations are often difficult to read, pronounce and spell. Moreover, this is a part of the world which today remains remote from the West culturally while political tensions have impeded mutual understanding. However, once you get a handle on the general geography of the area and its history, the art reveals itself as uniquely beautiful, intimate and fascinating in its complexity.

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

The region lacks stone (for building), precious metals and timber. Historically, it has relied on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture. Here, for the first time, thanks to ample food and a strong administrative class, the West develops a very high level of craft specialization and artistic production.

Dr. Senta German, “Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/ancient-near-east-cradle-of-civilization/.

Chronology

Smarthistory, “Tiny timeline: ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in a global context, 5th–3rd millennia B.C.E.,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2020, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/tiny-timeline-ancient-egypt-and-mesopotamia-in-a-global-context-5th-3rd-millennia-bce/.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/2s_6tsskzWY?si=echxO1SG0j4vYP1T

marthistory, “Tiny timeline: ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in a global context, 2nd–1st millennia B.C.E.,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2020, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/tiny-timeline-ancient-egypt-and-mesopotamia-in-a-global-context-2nd-1st-millennia-b-c-e/.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/UEhsHIXUN7Q?si=8ppP5sTvOaBVlQYc

Cuneiform

The earliest writing we know of dates back to around 3000 B.C.E. and was probably invented by the Sumerians, living in major cities with centralized economies in what is now southern Iraq. The earliest tablets with written inscriptions represent the work of administrators, perhaps of large temple institutions, recording the allocation of rations or the movement and storage of goods. Temple officials needed to keep records of the grain, sheep, and cattle entering or leaving their stores and farms and it became impossible to rely on memory. So, an alternative method was required and the very earliest texts were pictures of the items scribes needed to record (known as pictographs).

Early writing tablet recording the allocation of beer, 3100–3000 B.C.E, Late Prehistoric period, clay, probably from southern Iraq. (© Trustees of the British Museum) The symbol for beer, an upright jar with pointed base, appears three times on the tablet. Beer was the most popular drink in Mesopotamia and was issued as rations to workers. Alongside the pictographs are five different shaped impressions, representing numerical symbols. Over time these signs became more abstract and wedge-like, or “cuneiform.” The signs are grouped into boxes and, at this early date, are usually read from top to bottom and right to left. One sign, in the bottom row on the left, shows a bowl tipped towards a schematic human head. This is the sign for “to eat.”

Writing, the recording of a spoken language, emerged from earlier recording systems at the end of the fourth millennium. The first written language in Mesopotamia is called Sumerian. Most of the early tablets come from the site of Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, and it may have been here that this form of writing was invented.

These texts were drawn on damp clay tablets using a pointed tool. It seems the scribes realized it was quicker and easier to produce representations of such things as animals, rather than naturalistic impressions of them. They began to draw marks in the clay to make up signs, which were standardized so they could be recognized by many people.

From these beginnings, cuneiform signs were put together and developed to represent sounds, so they could be used to record spoken language. Once this was achieved, ideas and concepts could be expressed and communicated in writing.

Cuneiform is one of the oldest forms of writing known. It means “wedge-shaped,” because people wrote it using a reed stylus cut to make a wedge-shaped mark on a clay tablet. Letters enclosed in clay envelopes, as well as works of literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh have been found. Historical accounts have also come to light, as have huge libraries such as that belonging to the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal. Cuneiform writing was used to record a variety of information such as temple activities, business, and trade. Cuneiform was also used to write stories, myths, and personal letters. The latest known example of cuneiform is an astronomical text from 75 C.E. During its 3,000-year history, cuneiform was used to write around 15 different languages including Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Elamite, Hittite, Urartian, and Old Persian.

Cuneiform tablets at the British Museum

The department’s collection of cuneiform tablets is among the most important in the world. It contains approximately 130,000 texts and fragments and is perhaps the largest collection outside of Iraq. The centerpiece of the collection is the Library of Ashurbanipal, comprising many thousands of the most important tablets ever found. The significance of these tablets was immediately realized by the Library’s excavator, Austin Henry Layard, who wrote:

They furnish us with materials for the complete decipherment of the cuneiform character, for restoring the language and history of Assyria, and for inquiring into the customs, sciences, and . . . literature, of its people.

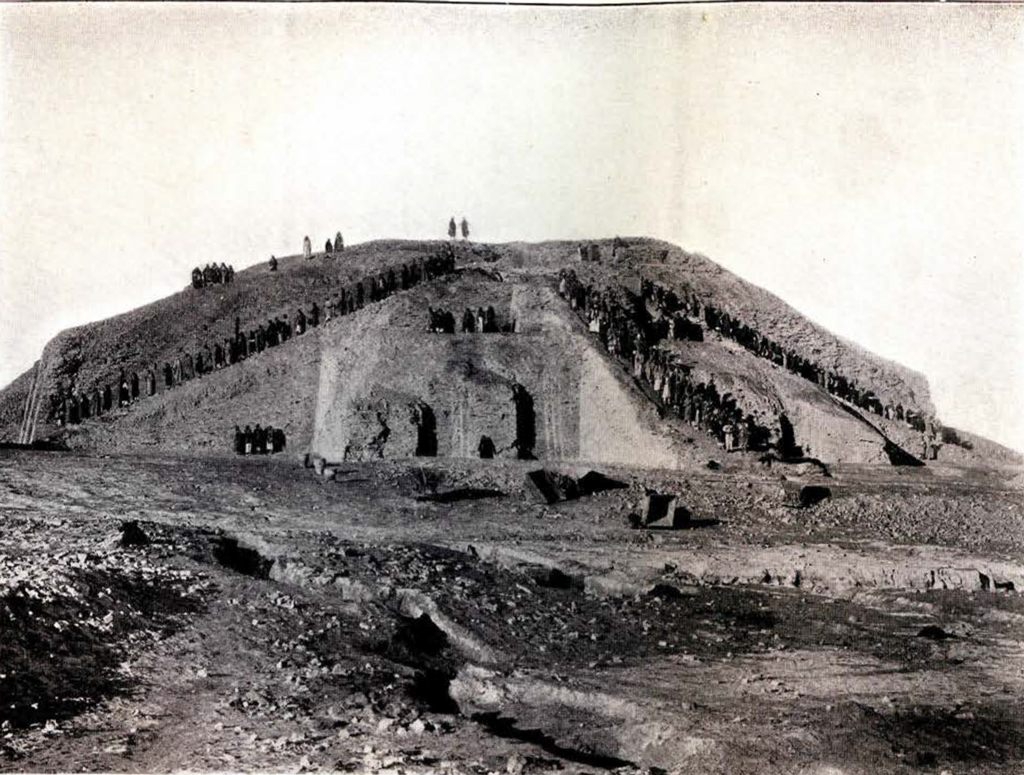

The Library of Ashurbanipal is the oldest surviving royal library in the world. British Museum archaeologists discovered more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments at his capital, Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik). Alongside historical inscriptions, letters, and administrative and legal texts, were found thousands of divinatory, magical, medical, literary and lexical texts. This treasure-house of learning has held unparalleled importance to the modern study of the ancient Near East ever since the first fragments were excavated in the 1850s.

Literacy was not widespread in Mesopotamia. Scribes, nearly always men, had to undergo training, and having successfully completed a curriculum became entitled to call themselves dubsar, which means “scribe.” They became members of a privileged élite who, like scribes in ancient Egypt, might look with contempt upon their fellow citizens.

Understanding of life in Babylonian schools is based on a group of Sumerian texts of the Old Babylonian period. These texts became part of the curriculum and were still being copied a thousand years later. Schooling began at an early age in the é-dubba, the “tablet house.” Although the house had a headmaster, his assistant, and a clerk, much of the initial instruction and discipline seems to have been in the hands of an elder student—the scholar’s “big brother.” All these had to be flattered or bribed with gifts from time to time to avoid a beating.

Apart from mathematics, the Babylonian scribal education concentrated on learning to write Sumerian and Akkadian using cuneiform and on learning the conventions for writing letters, contracts, and accounts. Scribes were under the patronage of the Sumerian goddess Nisaba. In later times her place was taken by the god Nabu, whose symbol was the stylus (a cut reed used to make signs in damp clay).

Deciphering cuneiform

The decipherment of cuneiform began in the eighteenth century as European scholars searched for proof of the places and events recorded in the Bible. Travelers, antiquaries, and some of the earliest archaeologists visited the ancient Near East where they uncovered great cities such as Nineveh. They brought back a range of artifacts, including thousands of clay tablets covered in cuneiform.

Scholars began the incredibly difficult job of trying to decipher these strange signs representing languages no-one had heard for thousands of years. Gradually the cuneiform signs representing these different languages were deciphered thanks to the work of a number of dedicated people.

Confirmation that they had succeeded came in 1857. The Royal Asiatic Society sent copies of a newly found clay record of the military and hunting achievements of King Tiglath-pileser I to four scholars: Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Edward Hincks, Julius Oppert, and William H. Fox Talbot. They each worked independently and returned translations that broadly agreed with each other.

This was accepted as proof that cuneiform had been successfully deciphered, but there are still elements that we don’t completely understand and the study continues. What we have been able to read, however, has opened up the ancient world of Mesopotamia. It has not only revealed information about trade, building, and government, but also great works of literature, history, and everyday life in the region.

© Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum, “Cuneiform, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, February 28, 2017, accessed March 18, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/cuneiform/.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism lost its dominant position when the Arabs invaded and defeated the Sasanian Empire, although it lived on especially in rural areas of Iran until the Turkish and Mongol invasions in the 11th and 13th centuries. It was only then that Zoroastrians withdrew to the desert towns of Kerman and Yazd. Today they form a religious minority in Iran of 10–30,000 persons. Soon after the Arab conquest of Iran in 651 C.E., there was an exodus of Zoroastrians from Iran to the Indian subcontinent where they settled and became known as the Parsis, and became an influential minority under British Colonial rule. From there Zoroastrians migrated to other parts of the world especially Britain, America, and Australia, where they form diaspora communities today.

What do Zoroastrians believe?

Zoroastrians believe that their religion was revealed by their supreme God, called Ahura Mazda, or ‘Wise Lord’, to a priest called Zarathustra (or Zoroaster, as the Greeks called him). Zarathustra is held to be the founder of the religion, and his followers call themselves Zartoshtis or Zoroastrians. Central to Zoroastrianism is the profound dichotomy between good and evil, and the idea that the world was created by God, Ahura Mazda, in order that the two forces could engage with one another and the evil one will be incapacitated. With this is the belief in an afterlife that is determined by the choices people make while on earth, the final and definitive defeat of evil at the end of time and a restoration of the world to its once perfect state.

What are the key sacred texts of Zoroastrianism?

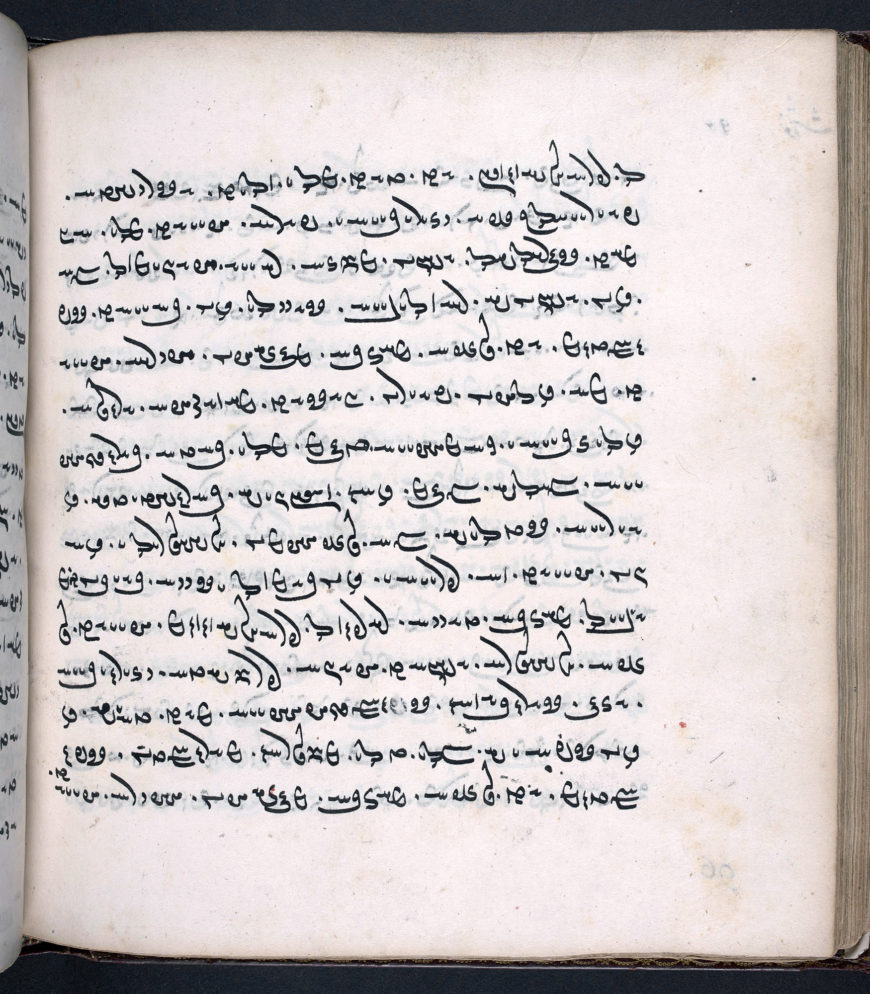

These religious ideas are encapsulated in the sacred texts of the Zoroastrians and assembled in a body of literature called the Avesta. Composed in an ancient Iranian language, Avestan, the Avesta is made up of different texts, most of which are recited in the Zoroastrian rituals, some of them by priests only, others by both priests and laypeople. These texts were composed orally at different times, and the oldest of them, the so-called Gathas, or ‘songs’ of Zarathustra, the Yasna Haptanghaiti and two prayers, probably date from some time in the mid- to late second millennium B.C.E. These texts are referred to as Older Avesta as their language is more archaic than that of the rest. The Younger Avesta is not only linguistically more recent, but also much greater in volume and shows a more advanced stage of the religion’s development. The Gathas are traditionally attributed to Zarathustra, the eponymous founder of the Zoroastrian tradition. All Avestan texts were composed and transmitted orally, although presumably from the late Sasanian period onwards there also existed a written tradition.

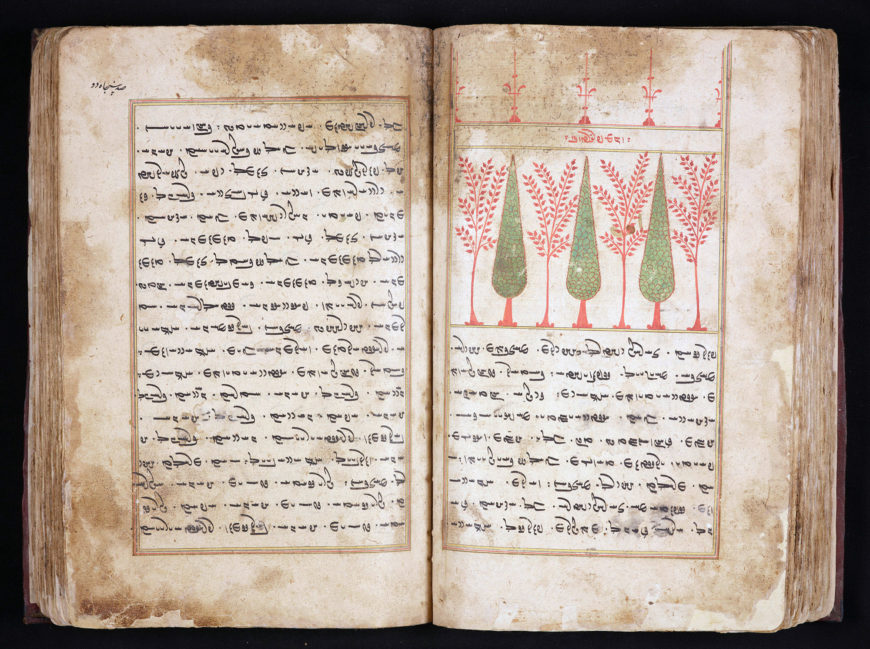

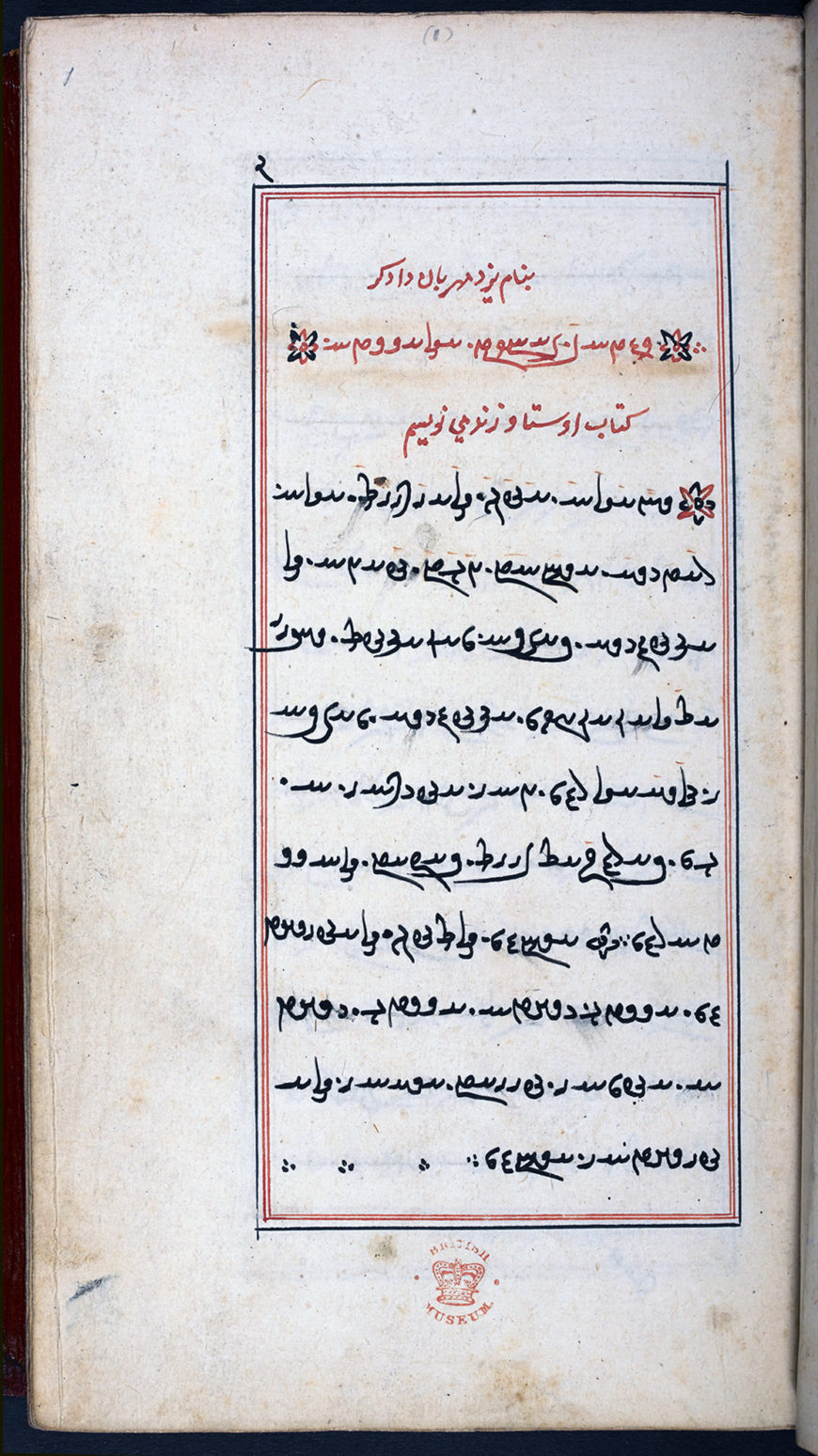

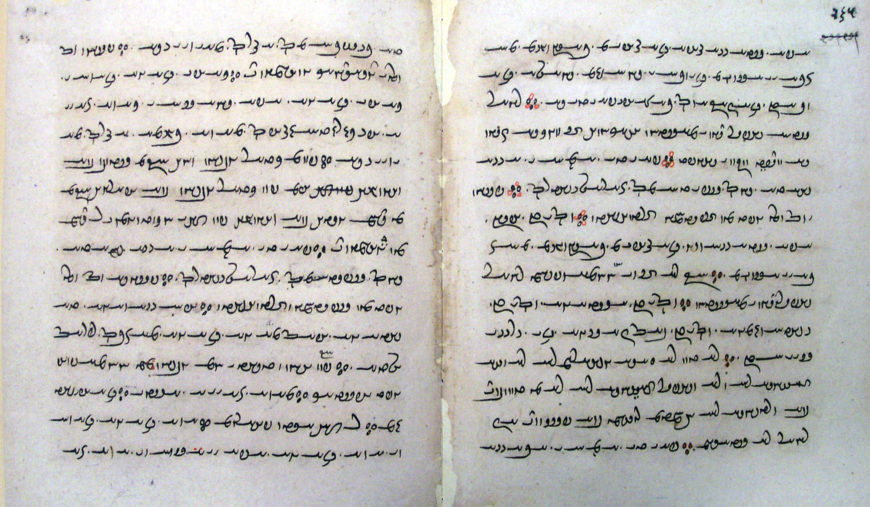

The poetic power of these texts, which are at the heart of the Avesta or Zoroastrian sacred literature, can still be appreciated today. The five Gathas consist of seventeen hymns, which together with the Yasna Haptanghaiti form the central portion of the key ritual of the Zoroastrian tradition, the Yasna of seventy-two chapters. The daily Yasna ceremony, which priests are still required to learn and recite by heart, is the most important of all Zoroastrian rituals. Folios 96-97 of this copy of the Yasna sādah, or ‘pure’ Yasna (i.e. the Avestan text without any commentary), contain the end of Yasna 43 and the beginning of Yasna 44. Arguably one of the most poetic sections of the whole Avesta, Yasna 44, consists of rhetorical questions posed to Ahura Mazda about the creation of the universe, such as who established the path of the sun and the stars, who made the moon wax and wane, and who holds the earth down below and prevents the clouds from falling down? The implied answer, of course, is that Ahura Mazda has arranged all of this.

Writing the ritual instructions in red ink helped the priests to navigate through the manuscript. Very few existing manuscripts also show illustrations. The British Library is home to one of them. It is a beautifully written and decorated copy of a ceremony called the Vīdēvdād, and shows seven coloured illuminations, all of trees. The manuscript was copied in Yazd, Iran, for a Zoroastrian of Kirman in 1647. The heading here has been decorated very much in the style of an illuminated Islamic manuscript.

The Vīdēvdād, or Vendidād as it is also known, is chiefly concerned with reducing pollution in the material world and represents a vital source for our knowledge and understanding of Zoroastrian purity laws. Folio 151 verso shows the beginning of chapter nine of the Zoroastrian law-book, which concerns the nine-night purification ritual (barashnum nuh shab) for someone who has been defiled by contact with a dead body.

The Yasna, Vīdēvdād and other rituals are recited and performed by priests inside the fire-temple. In addition, the Younger Avesta comprises devotional texts recited by both priest and lay members of the community, male and female alike. There are twenty-one hymns, or Yashts (Yt), dedicated to a variety of divinities whose praise is not only legitimised, but demanded by Ahura Mazda, who presides over them all. In the Zoroastrian calendar, each of the thirty days of the month is dedicated to one particular deity whose name it bears and whose hymn, or Yasht, is recited on that day.

The individual deities are also invoked for particular tasks. Mithra, for instance, is the deity who watches over contracts, while Anahita is especially close to women and helps them conceive and give birth. In addition, there are short prayers, blessings and other texts collected in the Small, or Khordah, Avesta.

In addition to manuscripts providing the Avestan texts to be recited in the rituals, there is a second group of bilingual manuscripts, which give the Avestan text together with its translation into Pahlavi.

As the tradition of the Avesta was entirely oral, its translation and explanation would have been memorized together with the Avesta, although the exegesis, called Zand, was more flexible and open to being altered and expanded. The Avesta was eventually written down in an alphabet designed especially for this purpose and developed on the basis of a cursive form of the Pahlavi script. The tradition of the Avesta and its exegesis that has come down to the present day is that of the province of Pars, the centre of imperial and priestly power during the Sasanian era. The Avesta script was invented artificially, presumably around 600 C.E., in the province of Pars in order to write down the sound of the recitation at a time when the meaning of the texts had long been forgotten. The script is based on the Pahlavi script which had been in use for many centuries for writing Middle Persian texts. The Pahlavi script in turn is derived from Aramaic, the chief administrative language of the Achaemenid Empire. It contains only consonants and is read from right to left.

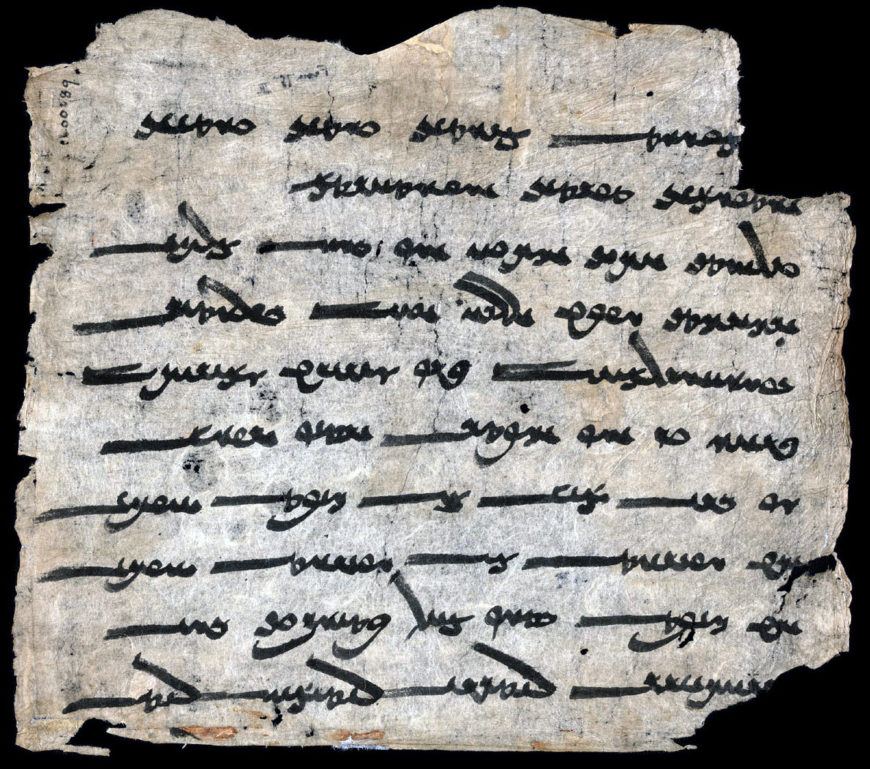

There is, however, a unique document from Central Asia, the so-called Sogdian Ashem vohū, which records the Avestan words of one of the Zoroastrian sacred prayers in Sogdian (a medieval Iranian language) script. Dating from the 9th century C.E., this document is the oldest extant Zoroastrian manuscript, predating the Avestan manuscripts by about 300 years. The Ashem vohū prayer occupies the first two lines of the text and shows features of the local pronunciation of Avestan in Sogdian, unaffected by the way Avestan was pronounced in the province of Pars. The rest of the text tells a story of Zarathushtra coming before and paying homage to a ‘supreme god’ (presumably Ahura Mazda) in Paradise.

The British Library, “An introduction to Zoroastrianism,” in Smarthistory, May 26, 2021, accessed March 18, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-zoroastrianism/.

Judaism

Judaism is the religion, philosophy and way of life of the Jewish people. Judaism is a monotheistic religion originating in the Hebrew Bible (also known as the Tanakh ) and explored in later texts, such as the Talmud . Judaism is considered by religious Jews to be the expression of the covenantal relationship God established with the Children of Israel.

Judaism claims a historical continuity spanning more than 3,000 years. Judaism has its roots as a structured religion in the Middle East during the Bronze Age. Of the major world religions, Judaism is considered one of the oldest monotheistic religions. The Hebrews / Israelites were already referred to as “Jews” in later books of the Tanakh such as the Book of Esther, with the term Jews replacing the title “Children of Israel”. Judaism’s texts, traditions and values strongly influenced later Abrahamic religions, including Christianity, Islam and the Baha’i Faith. Many aspects of Judaism have also directly or indirectly influenced secular Western ethics and civil law.

Origins

At its core, the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) is an account of the Israelites’ relationship with God from their earliest history until the building of the Second Temple (c. 535 BCE). Abraham is hailed as the first Hebrew and the father of the Jewish people. As a reward for his act of faith in one God, he was promised that Isaac , his second son, would inherit the Land of Israel (then called Canaan). Later, Jacob and his children were enslaved in Egypt, and God commanded Moses to lead the Exodus from Egypt.

At Mount Sinai they received the Torah — the five books of Moses . These books, together with Nevi’im and Ketuvim are known as Tanakh, as opposed to the Oral Torah, which refers to the Mishna and the Talmud.

Eventually, God led them to the land of Israel where the tabernacle was planted in the city of Shiloh for over 300 years to rally the nation against attacking enemies. As time went on, the spiritual level of the nation declined to the point that God allowed the Philistines to capture the tabernacle. The people of Israel then told the prophet Samuel that they needed to be governed by a permanent king, and Samuel appointed Saul to be their King. When the people pressured Saul into going against a command conveyed to him by Samuel, God told Samuel to appoint David in his stead.

Antiquity

The United Monarchy was established under Saul and continued under King David and Solomon with its capital in Jerusalem. After Solomon’s reign the nation split into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel (in the north) and the Kingdom of Judah (in the south).

The Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrian ruler Sargon II in the late 8th century BCE, with many people from the capital Samaria being taken captive to Media and the Khabur River valley.

The Kingdom of Judah continued as an independent state until it was conquered by a Babylonian army in the early 6th century BCE, destroying the First Temple that was at the center of ancient Jewish worship. The Judean elite were exiled to Babylonia and this is regarded as the First Jewish Diaspora . Later many of them returned to their homeland after the subsequent conquest of Babylonia by the Persians seventy years later, a period known as the Babylonian Captivity. A new Second Temple was constructed, and old religious practices were resumed.

During the early years of the Second Temple , the highest religious authority was a council known as the Great Assembly, led by Ezra of the Book of Ezra. Among other accomplishments of the Great Assembly, the last books of the Bible were written at this time and the canon sealed. Hellenistic Judaism spread to Ptolemaic Egypt from the 3rd century BCE. After the Great Revolt (66–73 CE), the Romans destroyed the Temple. Hadrian built a pagan idol on the Temple grounds and prohibited circumcision; these acts of ethnocide provoked the Bar Kokhba revolt 132–136 CE after which the Romans banned the study of the Torah and the celebration of Jewish holidays, and forcibly removed virtually all Jews from Judea. This became known as the Second Jewish Diaspora . In 200 CE, however, Jews were granted Roman citizenship and Judaism was recognized as a religio licita (“legitimate religion”), until the rise of Gnosticism and Early Christianity in the fourth century.

Following the destruction of Jerusalem and the expulsion of the Jews, Jewish worship stopped being centrally organized around the Temple, prayer took the place of sacrifice, and worship was rebuilt around the community (represented by a minimum of ten adult men) and the establishment of the authority of rabbis who acted as teachers and leaders of individual communities.

Historical Jewish Groupings (to 1700)

Around the 1st century CE there were several small Jewish sects: the Pharisees , Sadducees , Zealots , Essenes , and Christians . After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, these sects vanished.

- Christianity survived, but by breaking with Judaism and becoming a separate religion.

- The Pharisees survived but in the form of Rabbinic Judaism (today, known simply as “Judaism”).

- The Sadducees rejected the divine inspiration of the Prophets and the Writings, relying only on the Torah as divinely inspired. Consequently, a number of other core tenets of the

- Pharisees’ belief system (which became the basis for modern Judaism), were also dismissed by the Sadducees.

- The Samaritans practiced a similar religion, which is traditionally considered separate from Judaism.

Like the Sadducees who relied only on the Torah, some Jews in the 8th and 9th centuries rejected the authority and divine inspiration of the oral law as recorded in the Mishnah (and developed by later rabbis in the two Talmuds), relying instead only upon the Tanakh.

Defining Character

Unlike other ancient Near Eastern gods, the Hebrew God is portrayed as unitary and solitary; consequently, the Hebrew God’s principal relationships are not with other gods, but with the world, and more specifically, with the people He created.

Judaism thus begins with an ethical monotheism — the belief that God is one, and concerned with the actions of humankind .

According to the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), God promised Abraham to make of his offspring a great nation. Many generations later, he commanded the nation of Israel to love and worship only one God; that is, the Jewish nation is to reciprocate God’s concern for the world. He also commanded the Jewish people to love one another; that is, Jews are to imitate God’s love for people. These commandments are but two of a large corpus of commandments and laws that constitute this covenant, which is the substance of Judaism.

Moreover, as a non-creedal religion, some have argued that Judaism does not require one to believe in God. For some, observance of Jewish law is more important than belief in God per se. In modern times, some liberal Jewish movements do not accept the existence of a personified deity active in history.

Jewish Bible

The Jewish Bible is an anthology of Judean texts written, composed, and compiled between the 8th century BCE and 2nd century BCE. Thus, the Hebrew Bible did not begin as a single book; rather, it developed over time through the compilation of many Judean texts. The texts, though, were not always understood as divinely inspired, authoritative, holy texts; the role of Judean texts in religious expression developed between the 6th century BCE and 1st century CE. (38)

The Jewish Bible includes the same thirty-nine books that comprise the Christian Old Testament. Jews, of course do not refer to these texts as the Old Testament, as the title suggests that these scriptures are in some way obsolete. Fittingly, the Jewish Bible is sometimes referred to as the Hebrew Bible as all but two of its thirty-nine books—Daniel and Ezra—were composed entirely in Hebrew. More commonly, Jews refer to their Bible as the Tanakh.

The term Tanakh is actually an acronym that stands for the three sections of the Hebrew Bible:

Torah

The section includes the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures, or the Pentateuch . They are referred to as the Torah, or Law , because they are comprised largely of legal materials, including the Ten Commandments. Nevi’im is the pluralized form of a Hebrew word that means prophet . This section includes the historical books in the Hebrew Bible (e.g. Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel, I and II Kings) along with the major prophetic books (e.g. Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel) and minor prophetic books (e.g. Amos, Habakkuk, Joel, Obadiah, etc.). Kethuvi’im is the pluralized form of a Hebrew word that means writing . This section is more or less a catch all for various literary genres including petitionary literature (Psalms and Lamentations), wisdom Literature (Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes), and one apocalyptic text (Daniel).

Jewish Legal Literature

The basis of Jewish law and tradition (halakha ) is the Torah (also known as the “Pentateuch” or the ”Five Books of Moses “). According to rabbinic tradition there are 613 commandments in the Torah. Some of these laws are directed only to men or to women, some only to the ancient priestly groups, the Kohanim and Leviyim (members of the tribe of Levi), some only to farmers within the Land of Israel. Many laws were only applicable when the Temple in Jerusalem existed, and fewer than 300 of these commandments are still applicable today.

While there have been Jewish groups whose beliefs were claimed to be based on the written text of the Torah alone (e.g., the Sadducees, and the Karaites), most Jews believed in what they call the oral law. These oral traditions were transmitted by the Pharisee sect of ancient Judaism, and were later recorded in written form and expanded upon by the rabbis.

Rabbinic Judaism (which derives from the Pharisees) has always held that the books of the Torah (called the written law) have always been transmitted in parallel with an oral tradition. To justify this viewpoint, Jews point to the text of the Torah, where many words are left undefined, and many procedures mentioned without explanation or instructions; this, they argue, means that the reader is assumed to be familiar with the details from other, i.e., oral, sources. This parallel set of material was originally transmitted orally, and came to be known as “the oral law.”

By the time of Rabbi Judah haNasi (200 CE), after the destruction of Jerusalem, much of this material was edited together into the Mishnah. Over the next four centuries this law underwent discussion and debate in both of the world’s major Jewish communities (in Israel and Babylonia), and the commentaries on the Mishnah from each of these communities eventually came to be edited together into compilations known as the two Talmuds. These have been expounded by commentaries of various Torah scholars during the ages.

Halakha, the rabbinic Jewish way of life, then, is based on a combined reading of the Torah, and the oral tradition — the Mishnah, the halakhic Midrash, the Talmud and its commentaries. The Halakha has developed slowly, through a precedent-based system.

Judaism by Wikipedia for Schools is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 .

World Religions Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

LITERATURE

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Read an English translation of the “Epic of Gilgamesh” from “Sacred-Texts.com

Video from Crash Course URL: https://youtu.be/C_OxZpaOShg

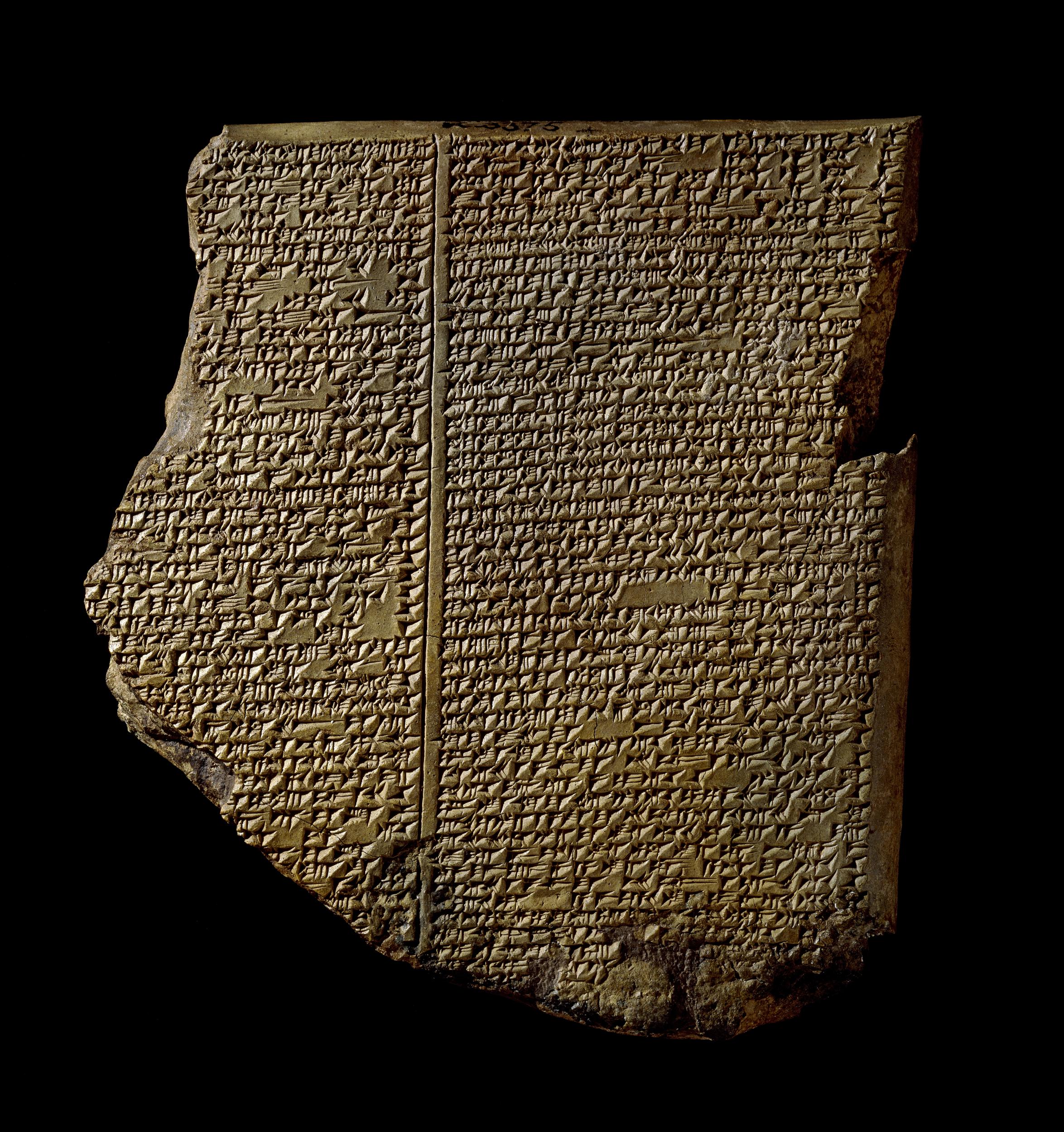

Epic of Gilgamesh and The Flood Tablet

The best known piece of literature from ancient Mesopotamia is the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary ruler of Uruk, and his search for immortality. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a huge work, the longest piece of literature in Akkadian (the language of Babylonia and Assyria). It was known across the ancient Near East, with versions also found at Hattusas (capital of the Hittites), Emar in Syria, and Megiddo in the Levant.

This, the eleventh tablet of the Epic, describes the meeting of Gilgamesh with Utnapishtim. Like Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Utnapishtim had been forewarned of a plan by the gods to send a great flood. He built a boat and loaded it with all his precious possessions, his kith and kin, domesticated and wild animals and skilled craftsmen of every kind.

Utnapishtim survived the flood for six days while mankind was destroyed, before landing on a mountain called Nimush. He released a dove and a swallow but they did not find dry land to rest on, and returned. Finally a raven that he released did not return, showing that the waters must have receded.

This Assyrian version of the Old Testament flood story is the most famous cuneiform tablet from Mesopotamia. It was identified in 1872 by George Smith, an assistant in The British Museum. On reading the text “he … jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself.”

Law Code of Hammurabi

Law is at the heart of modern civilization, and is often based on principles listed here from nearly 4,000 years ago.

Hammurabi of the city-state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and, by 1776 B.C.E., he was the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets. We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

Video URL: The Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi (youtube.com)

Read an English translation of the Code of Hammurabi on Yale’s ‘The Avalon Project.’

Copyright: Dr. Senta German, “Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hammurabi-2/.

Selected Books of the Hebrew Bible

Read an English translation of Genesis and Exodus at Sacred-texts.com

Read an English translation of the whole Bible at Sacred-texts.com

ARCHITECTURE

Jericho

Biblical reference

The site of Jericho is best known for its identity in the Bible and this has drawn pilgrims and explorers to it as early as the 4th century C.E.; serious archaeological exploration didn’t begin until the latter half of the 19th century. What continues to draw archaeologists to Jericho today is the hope of finding some evidence of the warrior Joshua, who led the Israelites to an unlikely victory against the Canaanites (“the walls of the city fell when Joshua and his men marched around them blowing horns” Joshua 6:1-27). Although unequivocal evidence of Joshua himself has yet to be found, what has been uncovered are some 12,000 years of human activity.

The most spectacular finds at Jericho, however, do not date to the time of Joshua, roughly the Bronze Age (3300-1200 B.C.E.), but rather to the earliest part of the Neolithic era, before even the technology to make pottery had been discovered.

Old walls

The site of Jericho rises above the wide plain of the Jordan Valley, its height the result of layer upon layer of human habitation, a formation called a Tell. The earliest visitors to the site who left remains (stone tools) came in the Mesolithic period (around 9000 B.C.E.) but the first settlement at the site, around the Ein as-Sultan spring, dates to the early Neolithic era, and these people, who built homes, grew plants, and kept animals, were among the earliest to do such anywhere in the world. Specifically, in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A levels at Jericho (8500-7000 B.C.E.) archaeologists found remains of a very large settlement of circular homes made with mud brick and topped with domed roofs.

As the name of this era implies, these early people at Jericho had not yet figured out how to make pottery, but they made vessels out of stone, wove cloth and for tools were trading for a particularly useful kind of stone, obsidian, from as far away as Çiftlik, in eastern Turkey. The settlement grew quickly and, for reasons unknown, the inhabitants soon constructed a substantial stone wall and exterior ditch around their town, complete with a stone tower almost eight meters high, set against the inner side of the wall. Theories as to the function of this wall range from military defense to keeping out animal predators to even combating the natural rising of the level of the ground surrounding the settlement. However, regardless of its original use, here we have the first version of the walls Joshua so ably conquered some six thousand years later.

Dr. Senta German, “Jericho,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/jericho/.

Catal Huyuk

The city of Çatalhöyük points to one of man’s most important transformations, from nomad to settled farmer.

Çatalhöyük or Çatal Höyük (pronounced “cha-tal hay OOK”) is not the oldest site of the Neolithic era or the largest, but it is extremely important to the beginning of art. Located near the modern city of Konya in south central Turkey, it was inhabited 9000 years ago by up to 8000 people who lived together in a large town. Çatalhöyük, across its history, witnesses the transition from exclusively hunting and gathering subsistence to increasing skill in plant and animal domestication. We might see Çatalhöyük as a site whose history is about one of man’s most important transformations: from nomad to settler. It is also a site at which we see art, both painting and sculpture, appear to play a newly important role in the lives of settled people.

Çatalhöyük had no streets or foot paths; the houses were built right up against each other and the people who lived in them traveled over the town’s rooftops and entered their homes through holes in the roofs, climbing down a ladder. Communal ovens were built above the homes of Çatalhöyük and we can assume group activities were performed in this elevated space as well.

Like at Jericho, the deceased were placed under the floors or platforms in houses and sometimes the skulls were removed and plastered to resemble live faces. The burials at Çatalhöyük show no significant variations, either based on wealth or gender; the only bodies which were treated differently, decorated with beads and covered with ochre, were those of children. The excavator of Çatalhöyük believes that this special concern for youths at the site may be a reflection of the society becoming more sedentary and required larger numbers of children because of increased labor, exchange, and inheritance needs.

Art is everywhere among the remains of Çatalhöyük—geometric designs as well as representations of animals and people. Repeated lozenges and zigzags dance across smooth plaster walls, people are sculpted in clay, pairs of leopards are formed in relief facing one another at the sides of rooms, hunting parties are painted baiting a wild bull. The volume and variety of art at Çatalhöyük is immense and must be understood as a vital, functional part of the everyday lives of its ancient inhabitants.

Many figurines have been found at the site, the most famous of which illustrates a large woman seated on or between two large felines. The figurines, which illustrate both humans and animals, are made from a variety of materials but the largest proportion are quite small and made of barely fired clay. These casual figurines are found most frequently in garbage pits, but also in oven walls, house walls, floors and left in abandoned structures. The figurines often show evidence of having been poked, scratched or broken, and it is generally believed that they functioned as wish tokens or to ward off bad spirits.

Nearly every house excavated at Çatalhöyük was found to contain decorations on its walls and platforms, most often in the main room of the house. Moreover, this work was constantly being renewed; the plaster of the main room of a house seems to have been redone as frequently as every month or season. Both geometric and figural images were popular in two-dimensional wall painting and the excavator of the site believes that geometric wall painting was particularly associated with adjacent buried youths.

Figural paintings show the animal world alone, such as, for instance, two cranes facing each other standing behind a fox, or in interaction with people, such as a vulture pecking at a human corpse or hunting scenes. Wall reliefs are found at Çatalhöyük with some frequency, most often representing animals, such as pairs of animals facing each other and human-like creatures. These latter reliefs, alternatively thought to be bears, goddesses or regular humans, are always represented splayed, with their heads, hands and feet removed, presumably at the time the house was abandoned.

The most remarkable art found at Çatalhöyük, however, are the installations of animal remains and among these the most striking are the bull bucrania. In many houses the main room was decorated with several plastered skulls of bulls set into the walls (most common on East or West walls) or platforms, the pointed horns thrust out into the communal space. Often the bucrania would be painted ochre red. In addition to these, the remains of other animals’ skulls, teeth, beaks, tusks, or horns were set into the walls and platforms, plastered and painted. It would appear that the ancient residents of Çatalhöyük were only interested in taking the pointy parts of the animals back to their homes!

How can we possibly understand this practice of interior decoration with the remains of animals? A clue might be in the types of creatures found and represented. Most of the animals represented in the art of Çatalhöyük were not domesticated; wild animals dominate the art at the site. Interestingly, examination of bone refuse shows that the majority of the meat which was consumed was of wild animals, especially bulls. The excavator believes this selection in art and cuisine had to do with the contemporary era of increased domestication of animals and what is being celebrated are the animals which are part of the memory of the recent cultural past, when hunting was much more important for survival.

Dr. Senta German, “Çatalhöyük,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/catalhoyuk/.

Ziggurats

Architecture: Power for Gods and Men

In the 4th millennium B.C.E. (c. 3200–3000 B.C.E.), Uruk in Mesopotamia was a city with a population of some 40,000 residents and another 80–90,000 working the fields in the environs. It was by far the greatest urban locus in the world at that time. The sheer power of Uruk’s agricultural wealth supported a larger population and afforded greater trade, all of which led to building on a monumental scale. Uruk was not alone; many of the city-states in the Ancient Near East had enormous buildings commissioned by the priestly class who controlled the agricultural surplus. This was a theocratic society—ruled by the priestly elite. Part of the power of this elite was their prominent representation in art. These, together with images of gods, were powerful symbols of power over vast groups of people.

The architecture of the Ancient Near East is among the first in the world to aim for monumental scale. Monumental architecture works in two ways: first, as something to look at in wonder because of its massive size and how it makes the viewer feel small next to it. Second, monumental architecture is powerful human-made topography, like building your own mountain to stand on top of it. In a region like southern Mesopotamia that is flat and marshy, to erect a massive structure, reaching skyward, mountain-like, would have seemed an accomplishment only a god could ordain. An example of just such a structure is the White Temple and Ziggurat at Uruk.

Not only did the White Temple and Ziggurat rise from the surrounding plane like a human-made peak but climbing the carefully constructed stairs to the elevated plateau and looking down offered a brand new sense of geographical and human domination. Only a god and his theocratic colleagues on earth could see to the creation of something so massive and this power would have been intensely felt by those holding that high ground. As a layperson, confronting that power would be humbling.

Dr. Senta German, “Rethinking approaches to the art of the Ancient Near East until c. 600 B.C.E.,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, June 28, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/rethinking-art-ancient-near-east/.

The Great Ziggurat of Ur has been reconstructed twice, in antiquity and in the 1980s—what’s left of the original?

The Great Ziggurat

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure, as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran, and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the Great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

Dr. Senta German, “Ziggurat of Ur,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/ziggurat-of-ur/.

Ishtar Gate

A Neo-Babylonian dynasty

The Babylonians rose to power in the late 7th century and were heirs to the urban traditions which had long existed in southern Mesopotamia. They eventually ruled an empire as dominant in the Near East as that held by the Assyrians before them.

This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia) because Babylon had also risen to power earlier and became an independent city-state, most famously during the reign of King Hammurabi.

In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd-millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar II largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar II purportedly built the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran). Though mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman writers, the “Hanging Gardens” may, in fact, be legendary.

The Ishtar Gate (today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. The whole gate was covered in lapis lazuli glazed bricks which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/U2iZ83oIZH0?si=QO7hXRPlhekRZK9f

Dr. Senta German, “The Ishtar Gate and Neo-Babylonian art and architecture,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 19, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/neo-babylonian/.

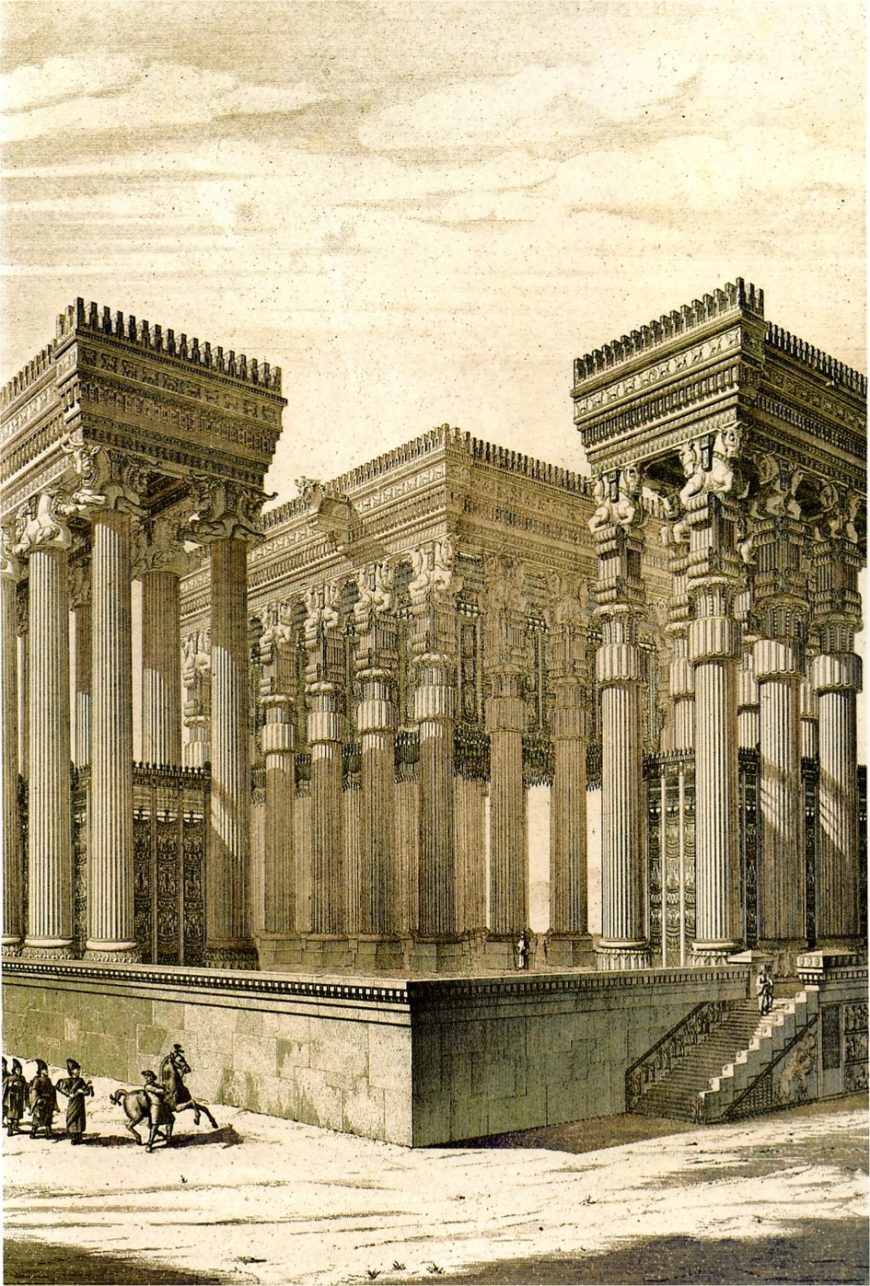

Persepolis

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Persian empire, lies some 60 km northeast of Shiraz, Iran. The earliest archaeological remains of the city date to c. 515 B.C.E. Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians”, was known to the Persians as Pārsa and was an important city of the ancient world, renowned for its monumental art and architecture. The site was excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter, and Erich Schmidt between 1931 and 1939. Its remains are striking even today, leading UNESCO to register the site as a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Persepolis was intentionally founded in the Marvdašt Plain during the later part of the sixth century B.C.E. It was marked as a special site by Darius the Great in 518 B.C.E. when he indicated the location of a “Royal Hill” that would serve as a ceremonial center and citadel for the city. This was an action on Darius’ part that was similar to the earlier king Cyrus the Great who had founded the city of Pasargadae. Darius the Great directed a massive building program at Persepolis that would continue under his successors Xerxes and Artaxerxes I. Persepolis would remain an important site until it was sacked, looted, and burned under Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 B.C.E.

The Apādana palace is a large ceremonial building, likely an audience hall with an associated portico. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan, meaning that the roof of the structure is supported by columns. Apādana is the Persian term equivalent to the Greek hypostyle (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστυλος hypóstȳlos). The footprint of the Apādana is c. 1,000 square meters; originally 72 columns, each standing to a height of 24 meters, supported the roof (only 14 columns remain standing today). The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls (above), eagles or lions, all animals represented royal authority and kingship.

The Apādana stairs and sculptural program

Petra

The great tombs and buildings of Petra

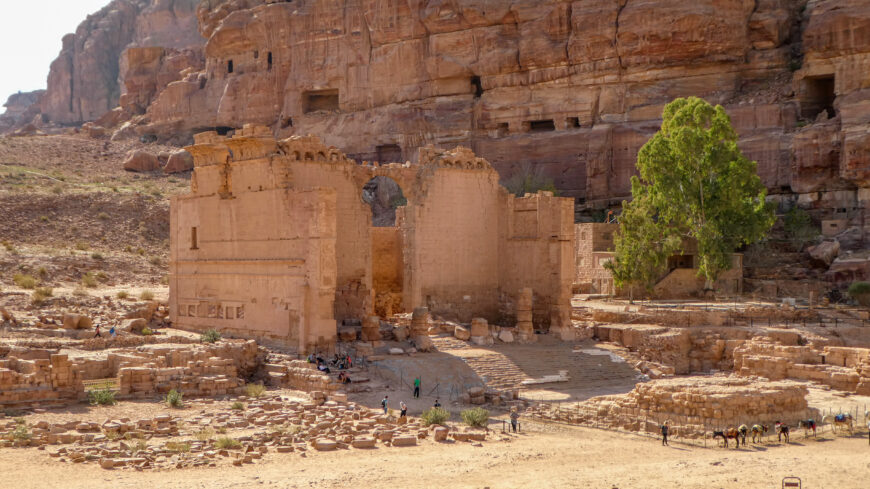

Petra was a well-developed city and contained many of the buildings and urban infrastructure that one would expect of a Hellenistic city. Recent archaeological work has radically reshaped our understanding of downtown Petra. Most of Petra’s great tombs and buildings were built before the Roman Empire annexed it in 106 C.E.

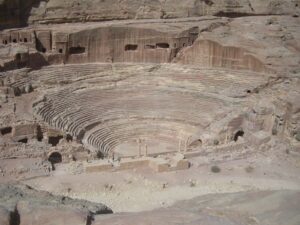

Petra had a large theater, which was probably built during the reign of Aretas IV, as well as a monumental colonnaded street. Important buildings graced both sides of the Wadi. On the south side of the street was a nymphaeum and a series of monumental spaces, which were once identified as markets. The so-called Lower Market has recently been excavated and shown to be a garden-pool complex. This stood adjacent to so-called Great Temple of Petra. Within the cella, or inner sanctuary room, of the Great Temple, a series of stone seats were discovered; this may suggest that the structure was not a temple, but an audience hall at least for part of its history.

Baths were also located in its vicinity. Opposite the so-called Great Temple is the Temple of Winged Lions, from which a unique god block of a female goddess was recovered. Column capitals at Petra are truly unique in part for their carvings of winged lions and elephants.

Just to the west, past a gate in a temenos, or sacred precinct, was the Qasr el-Bint, the most important temple in the city. It was also probably built under Aretas the IV, but we do not know to which gods the Qasr el-Bint was dedicated. Petra is also filled with more mundane architecture, including domestic residences, as well as the all-important water-catchment and storage systems that allowed life and agriculture to flourish here.

One of many Nabataean sites

Petra is often seen in isolation; in fact, it was one of many Nabataean sites; the Nabataean lands stretched from the Sinai and Negev in the west, as far north as Damascus at one point, and as far south as Egra, modern-day Madain Saleh, in Northern Saudi Arabia, which also had numerous rock-cut tombs, amongst others. At Egra an inscription attests to the presence of a Roman Legion at the site, marking the city as the southern most boundary of the Roman Empire in the Antonine Era. Khirbet et-Tannur was a major sanctuary in central Jordan; many of its reliefs are in the Cincinnati Museum of Art today.

The Nabataeans took an active role in their architectural and artistic creations, drawing upon the artistic vocabulary of the Hellenistic world and the ancient Near East. Rather than copying either one of these traditions, the Nabataeans actively selected and adopted certain elements for their tombs, dining pavilions, and temples to suit their needs and purposes, on both the group and individual level. Indeed, the Treasury and the Monastery could only have been conceived of and executed in Petra.

Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay, “Petra: urban metropolis,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/petra-urban-metropolis/.

VISUAL ARTS

Figurative Sculpture of Tell Asmar

Twelve statues from the “Square Temple” at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq)

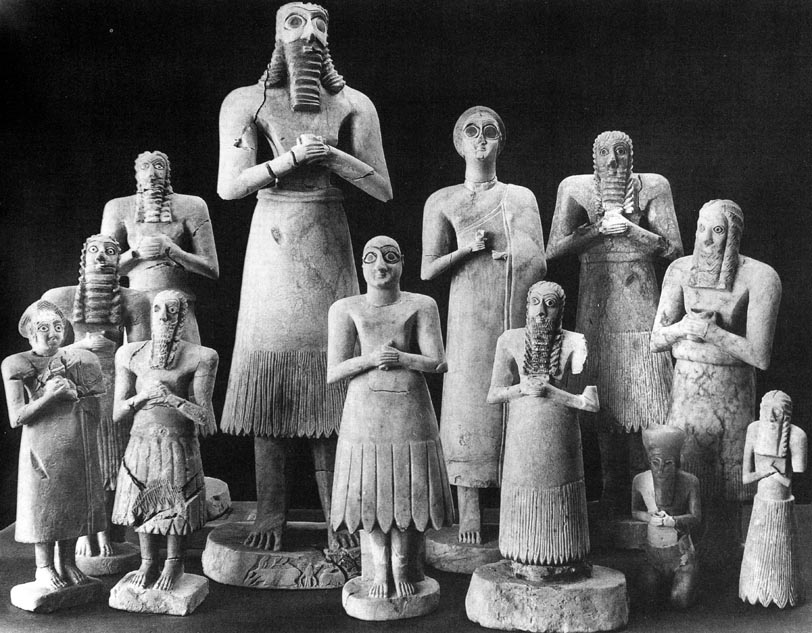

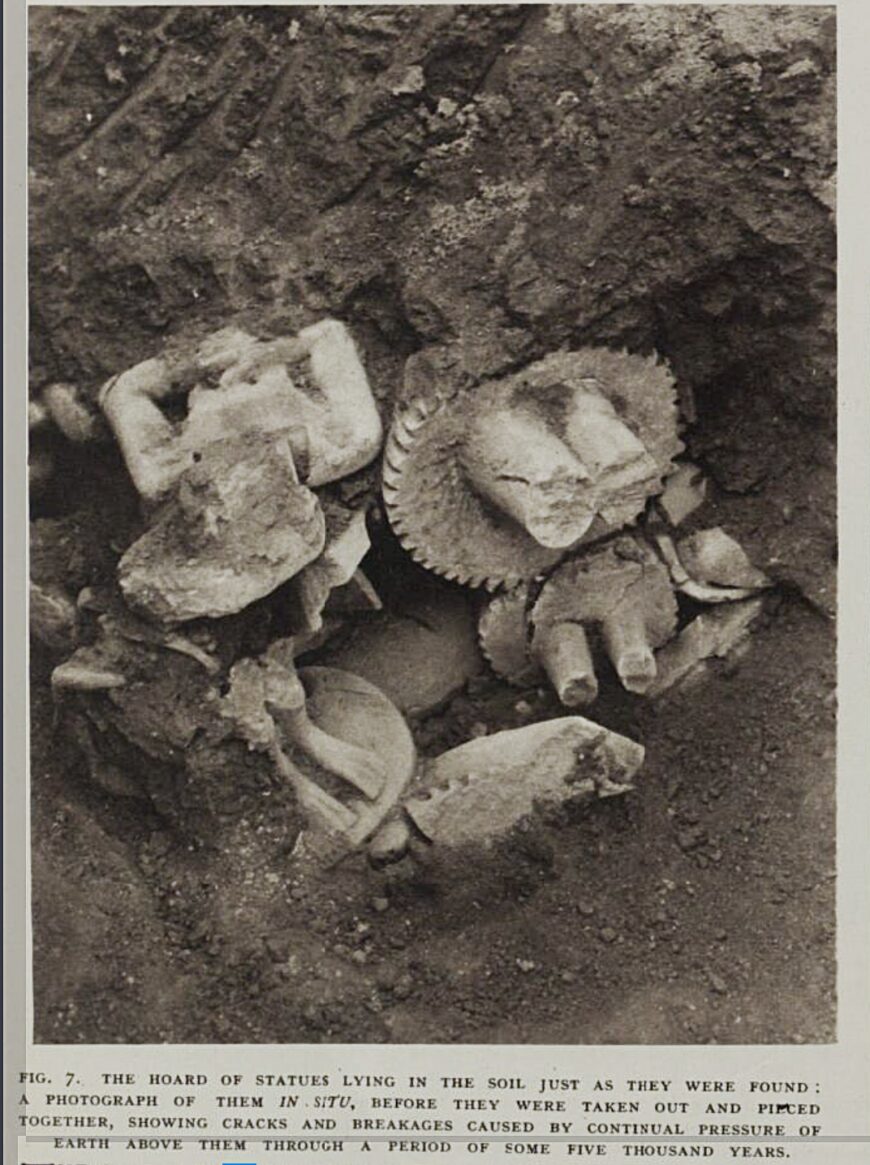

The group of twelve statues from Tell Asmar are among the most important examples of early sculpture from the Ancient Near East. The figures date to the Early Dynastic period of ancient Mesopotamia (2900–2350 B.C.E.) and were discovered during excavations in Iraq in 1934. These figures were found below the floor of a temple known as the “Square Temple” (likely dedicated to the God Abu). They range in size (from 9 to 28 inches; 23 to 72 cm) and in condition (some still displaying painting and inlay; others broken). All of them, however, appear deeply focused, staring straightforward, some with very large eyes, most with hands clasped, some holding cups. The figures were excavated by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago but are now dispersed in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum, New York, the National Museum of Iraq, and the Oriental Institute, Chicago.

The figures and their archaeological context

Of the twelve statues found, ten are male and two are female; eight of the figures are made from gypsum, two from limestone, and one (the smallest) from alabaster; all would have been painted. They appear to all be performing the same act and what we know about their archaeological context can help us understand what that might be. One statue in particular stands out from the rest: the tallest man with long dark flowing locks.

Standing Male Worshipper (votive figure), c. 2900-2600 B.C.E., from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq), gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone, bitumen, 11 5/8 x 5 1/8 x 3 7/8″ / 29.5 x 10 cm, Sumerian, Early Dynastic I-II (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Not gods, but adorants

From the Early Dynastic period sculptures such as these were common in temples. They are generally understood by art historians and archaeologists to be an image of the god to whom the temple was dedicated. They would be placed on raised platforms and were the recipients of gifts, as a proxy for the god.

However, the collection of statues from Tell Asmar appear to be of a different type, not images of gods and goddesses but rather adorants, mortals who stand in perpetual worship of the god of the temple. We know this because some of the statues are inscribed on the back or bottom with a personal name and prayer; others state “one who offers prayers.” Therefore, these sculptures represent a very early form of individual actions of faith, expressions of personal agency. Some of the sculptures are holding small cups which look a lot like a common cup of the era known as the solid-footed goblet. Hundreds of cups of this type were found deposited in a space near to the sanctuary where the sculptures were found, likely used to pour libations.

Who were these early pious actors? The statues were discovered together, packed one on top of another in several layers within a 33 x 20 inch (85 x 50 cm) pit and just by the altar of the temple. Because of the circumstances of this find they are assumed to be a group of alike sculptures, although of a special kind, for sure. Given the high status material from which they are made, the inclusion of writing as well as their privileged space within the temple, we might assume these represent elite people, both men and women, interestingly.

Although their style is abstract and there is no sense of portraiture among them, they are all unique in small ways, either in the rendering of hair, facial expression or even feet; the material of the inlays is also variable, some of white shell or black limestone and even one of lapis lazuli. These sculptures might also represent a clue about how society was changing in the Early Dynastic period. Archaeologists believe that this group of sculptures representing mortals from Tell Asmar were not only working spiritually on behalf of each individual but also as a group, asserting a new status of elite non-religious classes within the context of the temple.

One figure who stands out

As mentioned above, one figure stands out from the group. He is the tallest with curly locks flowing down over his wide shoulders, his face slightly upturned, making him seem somewhat less obsequious than the rest.

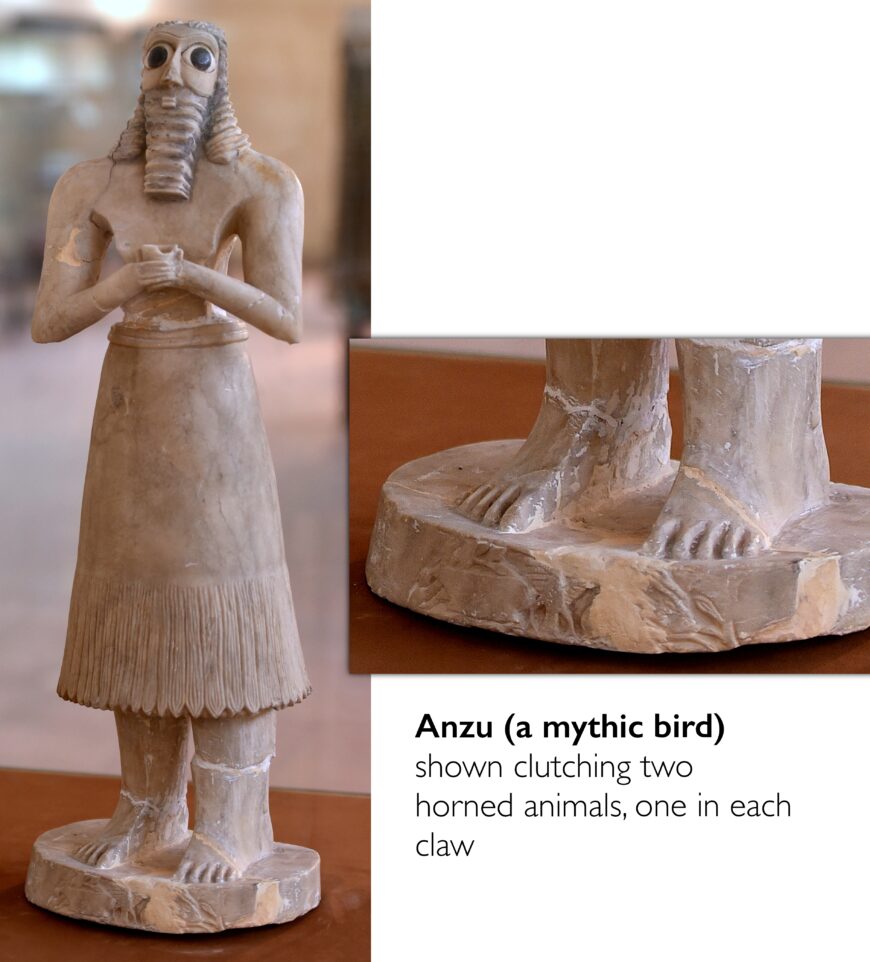

On the base of this sculpture there is a rough image carved as well, which also differentiates it from the others. This image shows an Anzu bird clutching two horned animals, one in each claw. This configuration—of Anzu clutching animals—is associated with the thunder god Ninurta (also known as Ningirsu), and also associated with the god of vegetation Abu.

This figure’s luxurious hair, more engaging face and godly image on the base has led to his identification of a very old character type in Ancient Near Eastern art and literature, the long-haired hero who is sometimes nude and sometimes belted.

If this identification is true, we might wonder if the person who dedicated this statue saw himself as a heroic, Gilgamesh-like character (Gilgamesh was a hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written during the late 2nd millennium B.C.E.).

Dr. Senta German, “Standing Male Worshipper (Tell Asmar),” in Smarthistory, July 26, 2023, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/standing-male-worshipper-from-the-square-temple-at-eshnunna-tell-asmar/.

Cylinder Seals

Signed with a cylinder seal

Cuneiform was used for official accounting, governmental and theological pronouncements and a wide range of correspondence. Nearly all of these documents required a formal “signature,” the impression of a cylinder seal.

A cylinder seal is a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse (intaglio) and hung on strings of fiber or leather. These often beautiful objects were ubiquitous in the Ancient Near East and remain a unique record of individuals from this era. Each seal was owned by one person and was used and held by them in particularly intimate ways, such as strung on a necklace or bracelet.

When a signature was required, the seal was taken out and rolled on the pliable clay document, leaving behind the positive impression of the reverse images carved into it. However, some seals were valued not for the impression they made, but instead, for the magic they were thought to possess or for their beauty.

The first use of cylinder seals in the Ancient Near East dates to earlier than the invention of cuneiform, to the Late Neolithic period (7600–6000 B.C.E.) in Syria. However, what is most remarkable about cylinder seals is their scale and the beauty of the semi-precious stones from which they were carved. The images and inscriptions on these stones can be measured in millimeters and feature incredible detail.

The stones from which the cylinder seals were carved include agate, chalcedony, lapis lazuli, steatite, limestone, marble, quartz, serpentine, hematite, and jasper; for the most distinguished there were seals of gold and silver. To study Ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals is to enter a uniquely beautiful, personal and detailed miniature universe of the remote past, but one which was directly connected to a vast array of individual actions, both mundane and momentous.

Why cylinder seals are interesting

Art historians are particularly interested in cylinder seals for at least two reasons. First, it is believed that the images carved on seals accurately reflect the pervading artistic styles of the day and the particular region of their use. In other words, each seal is a small time capsule of what sorts of motifs and styles were popular during the lifetime of the owner. These seals, which survive in great numbers, offer important information to understand the developing artistic styles of the Ancient Near East.

The second reason why art historians are interested in cylinder seals is because of the iconography (the study of the content of a work of art). Each character, gesture and decorative element can be “read” and reflected back on the owner of the seal, revealing his or her social rank and even sometimes the name of the owner. Although the same iconography found on seals can be found on carved stelae, terra cotta plaques, wall reliefs, and paintings, its most complete compendium exists on the thousands of seals which have survived from antiquity.

Dr. Senta German, “Cylinder seals,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/cylinder-seals/.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Cylinder seal with a modern impression,” in Smarthistory, December 21, 2015, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/cylinder-seal-and-modern-impression/.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/GpZYCOFAI_4?si=_6MVx9N2X5K8xd8d

Royal Standard of Ur

Intentionally buried as part of an elaborate ritual, this ornate object tells us so much, but also too little.

Standard of Ur, c. 2600–2400 B.C.E., 21.59 x 49.5 x 12 cm (British Museum). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Video URL: https://youtu.be/JWl6eolbQ2g?si=A9ivLgxBwHf7P8YX

The violence and grandeur of Sumerian kingship

The Standard of Ur is a fascinating rectangular box-like object which, through intricate mosaic scenes, presents the violence and grandeur of Sumerian kingship. It is made up of two long flat panels of wood (and two short sides) and is covered with bitumen (a naturally occurring petroleum substance, essentially tar) in which small pieces of carved shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli were set. It is thought to be a military standard, something common in battle for thousands of years: a readily visible object held high on a pole in the midst of the combat and paraded in victory to symbolize the army (or individual divisions of the army) of a war lord or general. Although we don’t know if this object ever saw the melee of battle, it certainly witnessed a grisly scene when it was deposited in one of the royal graves at the site of Ur in the mid-3rd millennium B.C.E.

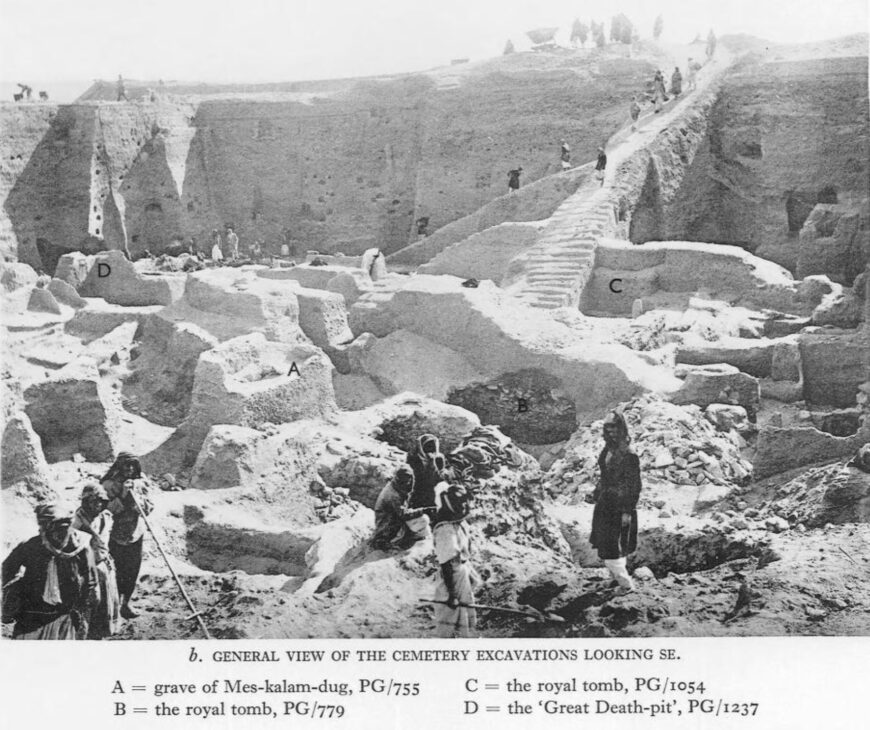

In the 1920s the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley worked extensively at Ur and in 1926 he uncovered a huge cemetery of nearly 2,000 burials spread over an area of 70 x 55 m (230 x 180 ft). Most graves were modest, however a group of sixteen were identified by Woolley as royal tombs because of their wealthier grave goods and treatment at interment.

Each of these tombs contained a chamber of limestone rubble with a vaulted roof of mud bricks. The main burial of the tomb was placed in this chamber and surrounded by treasure (offerings of copper, gold, silver and jewelry of lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, and shell). The main burial was also accompanied by several other bodies in the tomb, a mass grave outside the chamber, often called the Death Pit. We assume that all these individuals were sacrificed at the time of the main burial in a horrific scene of deference.

One of the royal graves (PG779) had four chambers but no death pit. It had been plundered in antiquity but one room was largely untouched and had the remains of at least four individuals. In the corner of this room the remains of the Standard of Ur were found. One of its long sides was found lying face down in the soil with the other one face up, which lead Woolley to conclude that it was a hollow structure; additional inlay were found on either side of the short ends and appeared to fill a triangular shape and which lead to the Standard being reconstructed with its sloping sides. The remains of the Standard were found above the right shoulder of a man whom Woolley thought had carried it attached to a pole. The identification of this object as a military standard is by no means secure; the hollow shape could just as easily have been the sound box of a stringed instrument, such as the Queen’s Lyre found in an adjacent tomb.

War and peace

The two sides of the Standard appear to be the two poles of Sumerian kingship, war and peace. The war side was found face up and is divided into three registers (bands), read from the bottom up, left to right. The story begins at the bottom with war carts, each with a spearman and driver, drawn by donkeys trampling fallen enemies, distinguished by their nudity and wounds, which drip with blood. The middle band shows a group of soldiers wearing fur cloaks and carrying spears walking to the right while bound, naked enemies are executed and paraded to the top band where more are killed.

In the center of the top register, we find the king, holding a long spear, physically larger than everyone else, so much so, his head breaks the frame of the scene. Behind him are attendants carrying spears and battle axes and his royal war cart ready for him to jump in. There is a sense of a triumphal moment on the battlefield, when the enemy is vanquished and the victorious king is relishing his win. There is no reason to believe that this is a particular battle or king as there is nothing which identifies it as such; we think it is more of a generic image of a critically important aspect of Ancient Near Eastern kingship.

The opposite peace panel also illustrates a cumulative moment, that of the celebration of the king, this time for great agricultural abundance which is afforded by peace. Again, beginning at the bottom left, we see men carrying produce on their shoulders and in bags and leading donkeys. In the central band, men lead bulls, sheep and goats, and carry fish. In the top register a grand feast is taking place, complete with comfortable seating and musical accompaniment.

On the left, the largest figure, the king, is seated wearing a richly flounce fur skirt, again so large, even seated, he breaks the frame. Was it an epic tale of battle that the singer on the far right is performing for entertainment as he plays a bull’s head lyre, again, like the Queen’s Lyre? We will never know but certainly such powerful images of Sumerian kingship tell us that whomever ended his life with the Standard of Ur on his shoulder was willing to give his life in a ritual of kingly burial.

Dr. Senta German, “Standard of Ur and other objects from the Royal Graves,” in Smarthistory, July 26, 2023, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/standard-of-ur-2/.

Assyrian Reliefs

Ashurnasirpal II

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II established Nimrud as his capital. Many of the principal rooms and courtyards of his palace were decorated with gypsum slabs carved in relief with images of the king as high priest and as victorious hunter and warrior. Many of these are displayed in the British Museum.

Ashurnasirpal II, whose name (Ashur-nasir-apli) means, “the god Ashur is the protector of the heir,” came to the Assyrian throne in 883 B.C.E. He was one of a line of energetic kings whose campaigns brought Assyria great wealth and established it as one of the Near East’s major powers.

Ashurnasirpal mounted at least fourteen military campaigns, many of which were to the north and east of Assyria. Local rulers sent the king rich presents and resources flowed into the country. This wealth was use to undertake impressive building campaigns in a new capital city created at Kalhu (modern Nimrud). Here, a citadel mound was constructed and crowned with temples and the so-called North-West Palace. Military successes led to further campaigns, this time to the west, and close links were established with states in the northern Levant. Fortresses were established on the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and staffed with garrisons.

By the time Ashurnasirpal died in 859 B.C.E., Assyria had recovered much of the territory that it had lost around 1100 B.C.E. as a result of the economic and political problems at the end of the Middle Assyrian period.

Relief panels

Later kings continued to embellish Nimrud, including Ashurnasirpal II’s son, Shalmaneser III who erected the Black Obelisk depicting the presentation of tribute from Israel.

During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Assyrian kings conquered the region from the Persian Gulf to the borders of Egypt. The most ambitious building of this period was the palace of king Sennacherib at Nineveh. The reliefs from Nineveh in the British Museum include a depiction of the siege and capture of Lachish in Judah.

The finest carvings, however, are the famous lion hunt reliefs from the North Palace at Nineveh belonging to Ashurbanipal. The scenes were originally picked out with paint, which occasionally survives, and work like modern comic books, starting the story at one end and following it along the walls to the conclusion.

The Assyrians used a form of gypsum for the reliefs and carved it using iron and copper tools. The stone is easily eroded when exposed to wind and rain and when it was used outside, the reliefs are presumed to have been protected by varnish or paint. It is possible that this form of decoration was adopted by Assyrian kings following their campaigns to the west, where stone reliefs were used in Neo-Hittite cities like Carchemish. The Assyrian reliefs were part of a wider decorative scheme which also included wall paintings and glazed bricks.

The reliefs were first used extensively by king Ashurnasirpal II at Kalhu (Nimrud). This tradition was maintained in the royal buildings in the later capital cities of Khorsabad and Nineveh.

The British Museum, “Assyrian Sculpture,” in Smarthistory, February 28, 2017, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/assyrian-sculpture/.

A military culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium B.C.E., led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

Luxurious palaces

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Ashurnasirpal II, to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Silent video reconstructs the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Video URL: https://youtu.be/5VCldg1TdHc?si=FQS64CDV8cuLGCBy

This silent video reconstructs the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (near modern Mosul in northern Iraq) as it would have appeared during his reign in the ninth century B.C.E. The video moves from the outer courtyards of the palace into the throne room and beyond into more private spaces, perhaps used for rituals. (According to news sources, this important archaeological site was destroyed with bulldozers in March 2015 by the militants who occupy large portions of Syria and Iraq.)

Feats of bravery

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength, and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

The destruction of Susa

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa. In one relief, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Dr. Senta German, “Assyria, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, May 14, 2019, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/assyrian-art-an-introduction/.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

Naram-Sin leads his victorious army up a mountain, as vanquished Lullubi people fall before him.

This monument depicts the Akkadian victory over the Lullubi Mountain people. In the 12th century B.C.E., a thousand years after it was originally made, the Elamite king, Shutruk-Nahhunte, attacked Babylon and, according to his later inscription, the stele was taken to Susa in what is now Iran. A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or relief carving.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Victory Stele of Naram-Sin,” in Smarthistory, November 24, 2015, accessed March 21, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/victory-stele-of-naram-sin/.