50 EUROPE

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Romanticism

- William Wordsworth

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Mary Shelley

- Realism

- Charles Baudelaire

- Gustave Flaubert

- Christina Rosetti

- Leo Tolstoy

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- Henrik Ibsen

- H.G. Wells

- W.B. Yeats

- Modernism

- Virginia Woolf

- James Joyce

- Franz Kafka

- T.S. Eliot

- Wilfred Owen

- Seamus Heaney

- Romanticism

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Music

- Romantic Era

- Art Song

- Piano Music

- Program Music

- Nationalism

- Romantic Opera

- Twentieth Century

- Impressionism

- Expressionism and Serialism

- Primitivism

- Electronic Music/Music Concrete

- Romantic Era

- Music

- Visual Arts

- Romanticism

- Introduction to Romanticism

- Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on His Imperial Throne

- Painting colonial culture: Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque

- Theodore Gericault, Raft of the Medusa

- Eugene Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People

- Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808

- Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring One of His Sons

- John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows

- J.M.W. Turner, Slave Ship

- Early Photography: Niepce, Talbot, and Muybridge

- Pre-Raphaelites

- Introducing the Pre-Raphaelits

- Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Proserpine

- Realism

- A Beginner’s Guide to Realism

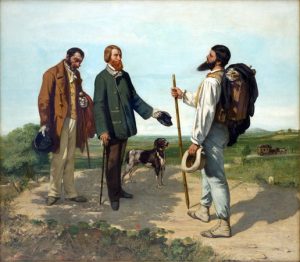

- Gustave Courbet, Bonjour Monsieur Courbet

- Edouard Manet, Olympia

- Edouard Manet, Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass)

- Impressionism

- Impressionism, an Introduction

- Edgar Degas, The Dance Class

- Berthe Morisot, The Cradle

- August Renoir, Moulin de la Galette

- August Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party

- Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral Series

- Claude Monet, Les Nympheas (The Water Lilies)

- Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte- 1884

- Vincent Van Gosh, The Starry Night

- Paul Cezanne, Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses)

- August Rodin, The Burghers of Calais

- Art Nouveau

- Gustav Klimt, The Kiss

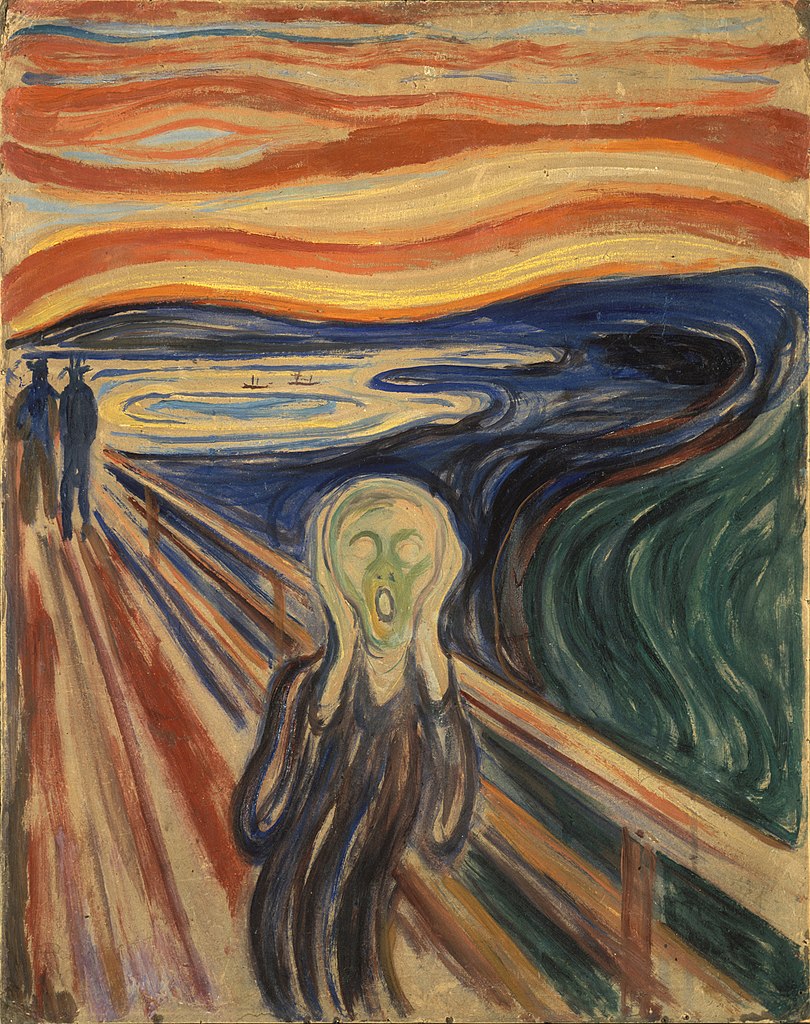

- Edvard Munch, The Scream

- Fauvism

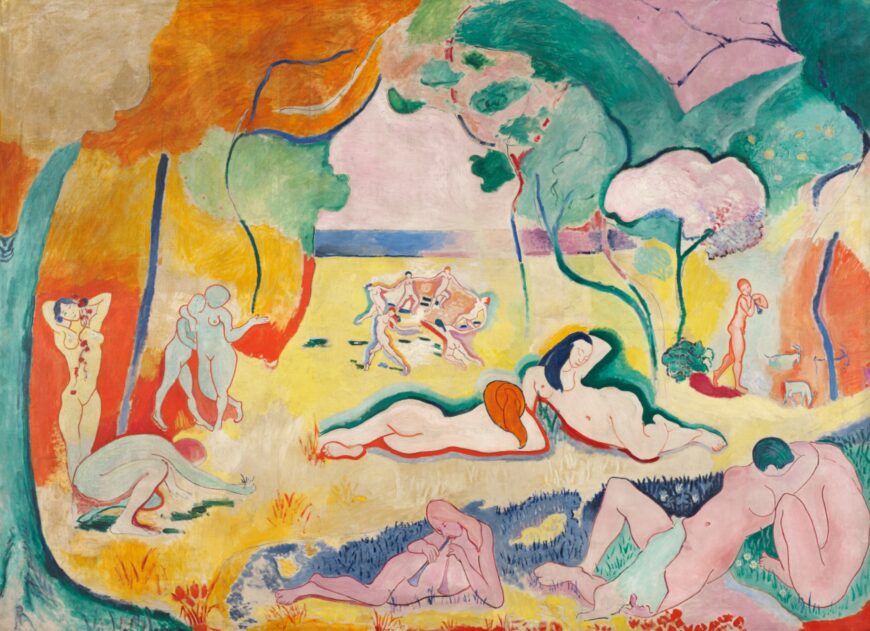

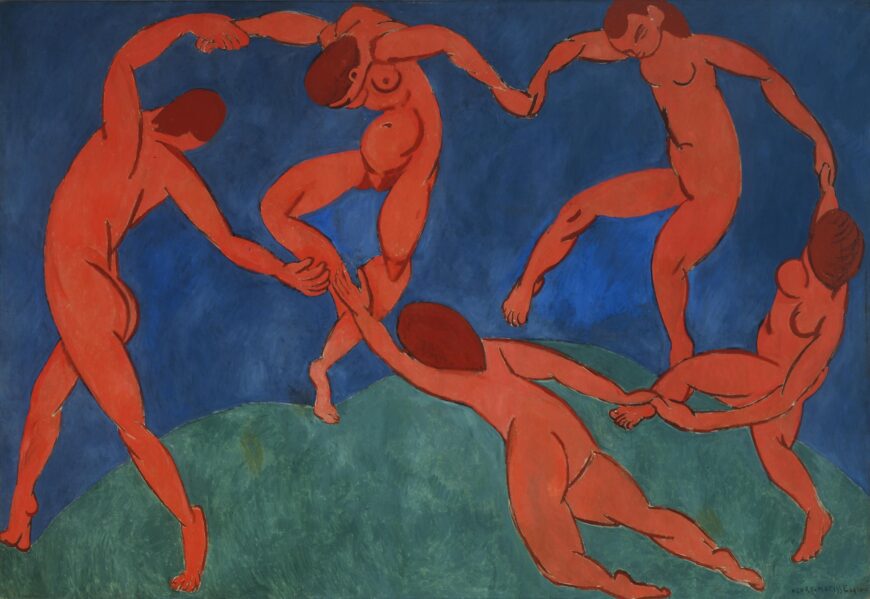

- Introduction to Fauvism

- Henri Matisse, Dance I

- Expressionism

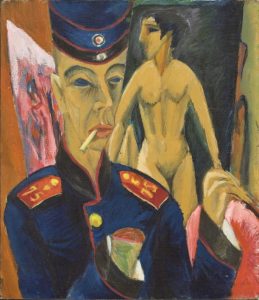

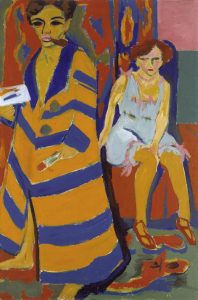

- Expressionism, an introduction

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait As a Soldier

- Egon Schiele, Portrait of Wally

- Vasily Kandinsky, Improvisation 28 (second version)

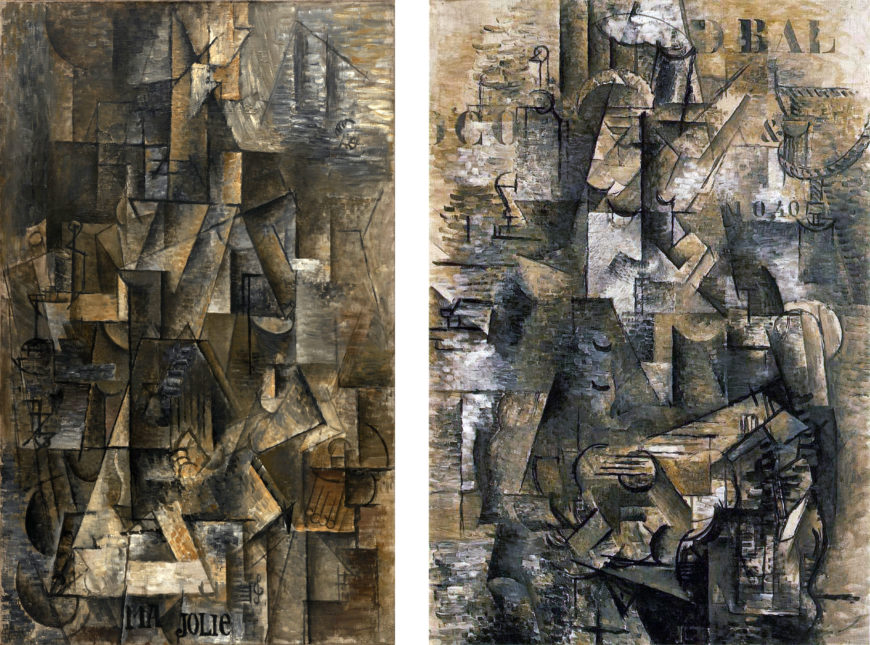

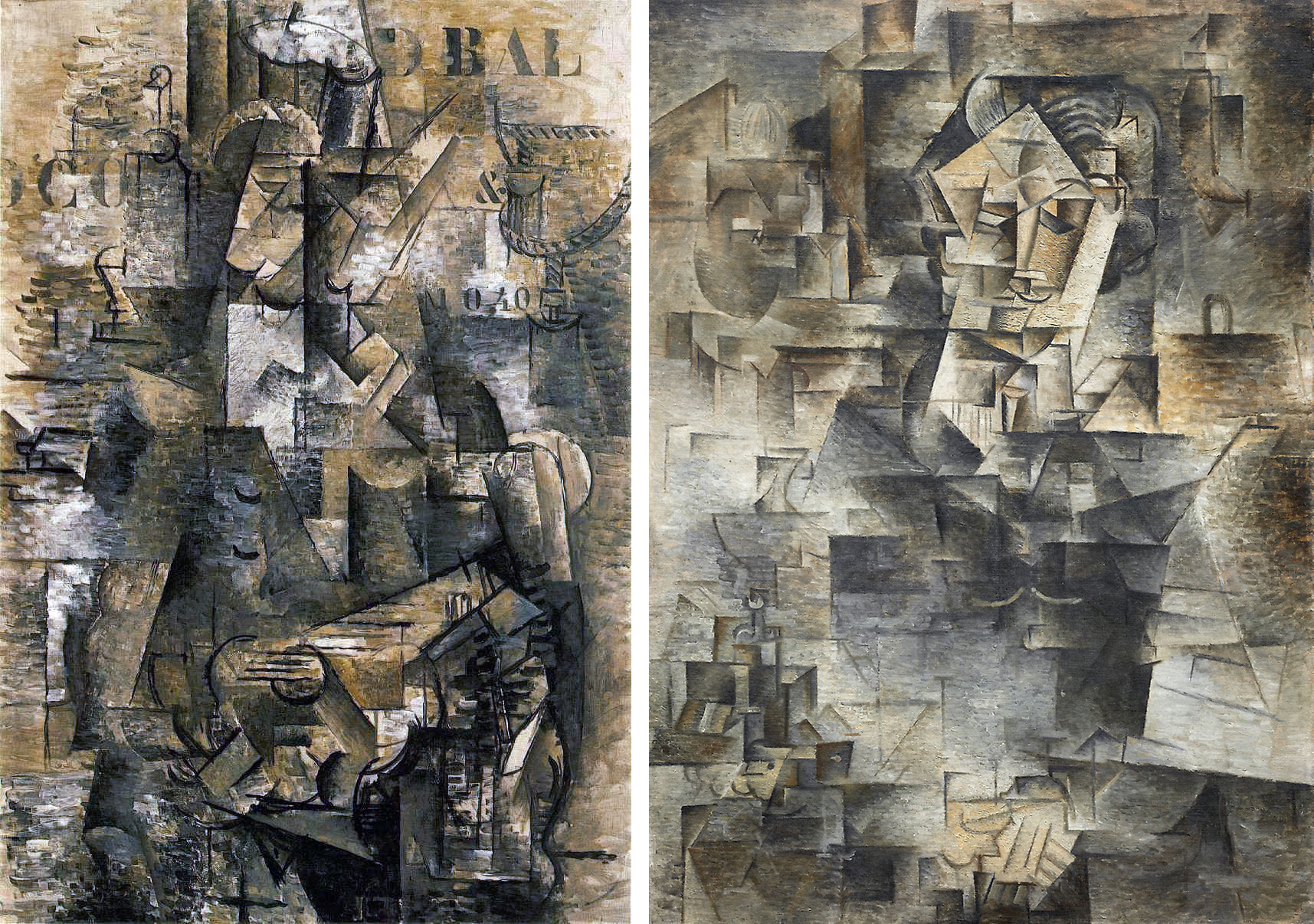

- Cubism

- Inventing Cubism

- Pablo Picasso, Guernica

- Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, Two Cubist Musicians

- Dada

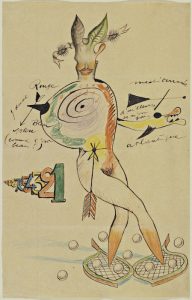

- Introduction to Dada

- Marcel Duchamp, The Fountain

- Hannah Hoch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Wieman Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany

- Surrealism

- Surrealism: An Introduction

- Rene Magritte, The Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe)

- Salvador Dali, The Persistence of Memory

- What Is Degenerate Art?

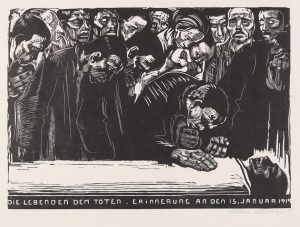

- Kathe Kollwitz, In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht

- Postwar Art

- Alberto Giacometti, Walking Man II

- Henry Moore, Reclining Figure

- Joseph Beuys, Celtic+~~~~ and Conceptual Performance

- Marina Abramovic, The Artist is Present

- Romanticism

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Marxism

Unlike Enlightenment social theory, Marxist theories did not try to solve specific social problems that arose from industrialization and urbanization. Rather, they advocated removing the economic system that they felt caused these problems—capitalism. When German philosophers Karl Marx and Frederick Engels published The Communist Manifesto in 1848, they made a prediction: the workers would overthrow capitalism in the most advanced industrial nation, England. The natural forces of history, they argued, made this revolution inevitable. They derived their views of these historical forces from the work of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) on the dialectic method.

Hegel argued that history itself was the movement created by the interaction between a thesis (an original state) and a force countering that original state (antithesis), resulting in a new and higher state (synthesis). This dialectic can be likened to a grade report: based on the original grades (the thesis), a student will ideally reflect on their performance and address areas of weakness (antithesis) to ultimately arrive at a higher understanding of the topics under study (synthesis).

Hegel argued that in various eras of history, Absolute Spirit—which might be understood in many ways, including God or the collective human consciousness—confronts its own essence and transitions to a higher state. Hegel saw this most clearly in the life of Jesus and the birth of Christianity. Hegel presents Jesus as a rational philosopher who reflects on and confronts Judaism—antithesis challenging thesis. The resurrection of Jesus following his crucifixion symbolizes an awakened consciousness both in the individual of Jesus and in humanity. Within this framework, the birth of Christianity following Jesus’s resurrection is viewed as the synthesis, the higher state (Dale 2006).

In contrast to Hegel’s idealistic dialectic, Karl Marx (1818–1883) proposed a view of the dialectic called dialectical materialism. Dialectical materialism identities the contradictions within material, real-world phenomena as the driving force of change. Most important to Marx were the economic conflicts between social classes. The Communist Manifesto, written by Marx and his collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) states, “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (Marx and Engels [1969] 2000, ch. 1). Marx and Engels note that in every epoch of history (as understood at the time) society has been divided into social orders and that tensions between these social orders determine the direction of history, rather than the realization of any abstract ideals. Specifically, they identified the colonization of the Americas and the rise of trade with India and China as the revolutionary forces that created and enriched the bourgeois class, ultimately resulting in the death of feudalism. Similarly, Marx regarded the clash of economic interests between the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) and the proletariat (workers) as the contradiction that would bring down capitalism and give rise to a classless society (Marx and Engels [1969] 2000).

Marx laid out a detailed plan for how the proletariat revolution would occur. Marx proposed the concept of surplus value as a contradictory force within capitalism. Surplus value was the profit the capitalists made above and beyond the wages of the workers. This profit strengthens the capitalists’ monetarily and so gives them more power over the workers and a greater ability to exploit them. Marx viewed this surplus value as a key part of the “economic law of motion of modern society” that would inevitably lead to revolution (Marx [1954] 1999).

Despite there being competition among workers for jobs, Marx believed that conflict with their employers would bind them. As capitalism advanced, the workers would form into a class of proletariats, which would then form trade unions and political parties to represent its interests. As the revolution advanced, the most resolute members of the working-class political parties, those with the clearest understanding of the movement, would establish the communist party. The proletariat, led by the communists, would then “wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the State” (Marx and Engels [1969] 2000, ch. 2). The communist party would need to rule society as “the dictatorship of the proletariat” and enact reforms that would lead to a classless society.

These developments did, in fact, materialize—but in Russia, not in England, as Marx had predicted. Marx had expected the revolution to begin in England, since it was the most industrial society, and to spread to other nations as their capitalist economies advanced to the same degree. The unfolding of actual events in a way contrary to Marx’s predictions led Marxists and others to doubt the reliability of Marx’s system of dialectical materialism. This doubt was compounded by the realizations that the Russian communist party was responsible for killing millions of farmers and dissidents and that some working-class parties and unions were turning to fascism as an alternative to communism. By the early to mid-20th century, opponents of the capitalist system were questioning orthodox Marxism as a method of realizing the ideal of a government by the working class.

Copyright: Smith, Nathan. (2022). The Marxist Solution. In Introduction to Philosophy. OpenStax.

Existentialism

Video URL: https://youtu.be/YaDvRdLMkHs?si=LBhU5DjDOmvpECd6

Post-modernism

Many modern scholars embraced the idea that the world operates according to a set of overarching universal structures. This view proposes that as we continue to progress in terms of technological, scientific, intellectual, and social advancements, we come closer to discovering universal truths about these structures. This view of progression toward truth gave rise to a school of thought known as structuralism, which is pervasive in many academic fields of study, as discussed below. Postmodernism departs from this way of thinking in rejecting these ideas and contending that there exists no one reality that we can be certain of and no absolute truth.

The philosophical battle over whether there is one nonnegotiable reality took shape in conversations around structuralism and post-structuralism. Structuralists historically looked to verbal language and mathematics to show that symbols cannot refer to just anything we want them to refer to. For example, most people would say it is ridiculous to use the word car to refer to a dog. Rather, language and mathematics are universal systems of communication emerging from a universal structure of things. This claim sounds similar to Platonic idealism, in which the structures that ground our world are understood as intangible “forms.”

Freud’s Structuralism in Psychology

The theory of psychoanalysis is based on the idea that all humans have suppressed elements of their unconscious minds and that these elements will liberate them if they are confronted. This idea was proposed and developed by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). For Freud, psychoanalysis was not only a theory but also a method, which he used to free his patients from challenges such as depression and anxiety. In Freud’s early thinking, the “unconscious” was defined as the realm in which feelings, thoughts, urges, and memories that exist outside of consciousness reside. These elements of the unconscious were understood to set the stage for conscious experience and influence the human automatically (Westen 1999). Freud later abandoned the use of the word unconscious (Carlson et al. 2010, 453), shifting instead to three separate terms: id, referring to human instincts; superego, indicating the enforcer of societal conventions such as cultural norms and ethics (Schacter, Gilbert, and Wegner 2011, 481); and ego, describing the conscious part of human thought. With these three terms, Freud proposed a universal structure of the mind.

Post-structuralists point out that Freud’s ideas about psychoanalysis and universal structures of the mind cannot be proven. The subconscious foundations on which psychoanalysis is grounded simply cannot be observed. Some have argued that there is no substantive difference between the claims of psychoanalysts and those of shamans or other practitioners of methods of healing not grounded in empirical methods (Torrey 1986). French philosopher Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) and French psychoanalyst Felix Guattari (1930–1992) took an even harsher approach, presenting psychoanalysis as a means of reinforcing oppressive state control.

Belgian philosopher Luce Irigaray (b. 1930) and others have criticized Freud’s ideas from a feminist perspective, accusing psychoanalysts of excluding women from their theories. In this view, psychoanalysis is based on a patriarchal understanding. Those taking this view point out that Freud made a number of patriarchal claims, including that sexuality and subjectivity are inseparably connected, and that he viewed women as problematic throughout his life (Zakin 2011). Yet many psychoanalytic feminists express a critical appreciation for Freud, utilizing what they find valuable in his theories and ignoring other aspects.

Deconstruction

Closely related to post-structuralism is deconstruction. Accredited to Algerian-born French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), deconstruction aims to analyze a text to discover that which made it what it was. Derrida rejected the structuralist approach to textual analysis. In the structuralist framework, there was a focus on how a text fits into a larger framework of linguistic meaning and signifying (Barry 2002, 40). Derrida, among others, held that these structures were as arbitrary as other facets of language, such as the arbitrary decision to use “tree” to refer to a large plant with a bark, trunk, and leaves when we could have called it a “cell phone” and have procured the same symbolic use (Thiselton 2009). Derrida asserted that texts do not have a definitive meaning but rather that there are several possible and plausible interpretations. His argument was based on the assertion that interpretation could not occur in isolation. While Derrida did not assert that all meanings were acceptable, he did question why certain interpretations were held as more correct than others (Thiselton 2009).

When German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) famously declared that “God is dead,” he rejected God as a basis for morality and asserted that there is no longer (and never was) any ground for morality other than the human. The removal of the notion of sure foundations for ethical behavior and human meaning can stir a sense of anxiety, a fear of living without a place of certainty (Warnock 1978). This fear and anxiety inform the existential notion of the “absurd,” which is simply another way of stating that the only meaning the world has is the meaning that we give it (Crowell 2003). In this motion away from objective assertions of truth, one comes to what Nietzsche calls “the abyss,” or the world without the absolute logical structures and norms that provide meaning. The abyss is the world where nothing has universal meaning; instead, everything that was once previously determined and agreed upon is subject to individual human interpretation. Without the structures of fixed ethical mandates, the world can seem a perpetual abyss of meaninglessness.

Ethics in Post-structuralism

Although Nietzsche lived prior to Derrida, he engaged in a type of deconstruction that he referred to as genealogy. In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche traces the meaning of present morals to their historical origins. For example, Nietzsche argued that the concepts we refer to as “good” and “evil” were formed in history through the linguistic transformation of the terms “nobility” and “underclass” (Nietzsche 2007, 147–148). Nietzsche held that the upper classes at one time were thought to be “noble,” having characteristics that the lower classes were envious or and would want to emulate. Therefore, “noble” was considered not an ethical “good” but a practical “good.” A person simply had a better life if they were part of the ruling class. Over time, the concept of “noble” took on a more ideal meaning, and the practical characteristics (e.g., reputation, access to resources, influence, etc.) became abstract virtues. Because the lower classes were envious of the upper classes, they found a theoretical framework to subvert the power of the nobility: Judeo-Christian philosophy. In Judeo-Christian philosophy, the “good” is no longer just a synonym for the nobility but a spiritual virtue and is represented by powerlessness. “Evil” is represented by strength and is a spiritual vice. Nietzsche views this reversal as one of the most tragic and dangerous tricks to happen to the human species. In his view, this system of created morality allows the weak to stifle the power of the strong and slow the progress of humanity.

Foucault on Power and Knowledge

For French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984), “power” at the base level is the impetus that urges one to commit any action (Lynch 2011, 19). Foucault claimed that power has been misunderstood; it has traditionally been understood as residing in a person or group, but it really is a network that exists everywhere. Because power is inescapable, everyone participates in it, with some winning and others losing.

Foucault contended that power affects the production of knowledge. He argued that Nietzsche’s process of genealogy exposed the shameful origins of practices and ideas that some societies have come to hold as “natural” and “metaphysically structural,” such as the inferiority of woman or the justification of slavery. For Foucault, these and other systems aren’t just the way things are but are the way things have been developed to be by the powerful, for their own benefit. The disruptions promoted by critical theory are viewed as insurrections against accepted histories—disruptions that largely deal with a reimagining of how we know what we know—and understood as a weapon against oppression.

Critical Race Theory

One of the most controversial applications of critical theory concerns its study of race. Critical race theory approaches the concept of race as a social construct and examines how race has been defined by the power structure. Within this understanding, “Whiteness” is viewed as an invented concept that institutionalizes racism and needs to be dismantled. Critical race theorists trace the idea of “Whiteness” to the late 15th century, when it began to be used to justify the dehumanization and restructuring of civilizations in the Americas by Britain, Spain, France, Germany, and Belgium. As these colonizing nations established new societies on these continents, racism was built into their institutions. Thus, for example, critical race theorists argue that racism not as an anomaly but a characteristic of the American legal system. Ian Haney López’s White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race argued that racial norms in the United States are background assumptions that are legally supported and that impact the success of those socially defined by them. Critical race theory views the institutions of our society as replicating racial inequality.

The idea of institutionalized racism is not unique to critical race theory. Empirical studies, such as those carried out by W. E. B. Du Bois, have outlined the structure of institutionalized racism within communities. Critical race theories are unique in that they do not see policies that arise from these empirical studies as a solution because these policies, they argue, arise within a power structure that determines what we accept as knowledge. Instead, critical race theorists, like other branches of critical theory, turn to the philosopher, the teacher, or the student to relinquish their role as neutral observers and challenge the power structure and social institutions through dialog. Critics of this approach—and other critical theory approaches to education—worry that these programs seek to indoctrinate students in a manner that bears too close a resemblance to Maoist “self-criticism” campaigns.

Radical Democracy

“Radical democracy” can be defined as a mode of thought that allows for political difference to remain in tension and challenges both liberal and conservative ideas about government and society. According to radical democracy, the expectation of uniform belief among a society or portion of a society is opposed to the expressed and implied tenets of democracy (Kahn and Kellner 2007). If one wants freedom and equality, then disparate opinions must be allowed in the marketplace of ideas.

One strand of radical democracy is associated with Habermas’s notion of deliberation as found in communicative action. Habermas argued for deliberation, not the normalizing of ideas through peer pressure and governmental influence, as a way in which ideological conflicts can be solved. Though Habermas admitted that different contexts will quite naturally disagree over important matters, the process of deliberation was viewed as making fruitful dialogue between those with opposing viewpoints possible (Olson [2011] 2014). Another type of radical democracy drew heavily on Marxist thought, asserting that radical democracy should not be based on the rational conclusions of individuals but grounded in the needs of the community.

Copyright: Smith, Nathan. (2022). Postmodernism. In Introduction to Philosophy. OpenStax.

Feminism

Third wave feminism is, in many ways, a hybrid creature. It is influenced by second wave feminism, Black feminisms, transnational feminisms, Global South feminisms, and queer feminism. This hybridity of third wave activism comes directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries who have grown up in a world that supposedly does not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women have been guaranteed by law in most countries. The gap between law and reality—between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience—however, reveals the necessity of both old and new forms of activism. In a country where white women are paid only 75.3% of what white men are paid for the same labor (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2016), where police violence in black communities occurs at much higher rates than in other communities, where 58% of transgender people surveyed experienced mistreatment from police officers in the past year (James et. al 2016), where 40% of homeless youth organizations’ clientele are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (Durso and Gates 2012), where people of color—on average—make less income and have considerably lower amounts of wealth than white people, and where the military is the most funded institution by the government, feminists have increasingly realized that a coalitional politics that organizes with other groups based on their shared (but differing) experiences of oppression, rather than their specific identity, is absolutely necessary. Thus, Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake (1997) argue that a crucial goal for the third wave is “the development of modes of thinking that can come to terms with the multiple, constantly shifting bases of oppression in relation to the multiple, interpenetrating axes of identity, and the creation of a coalitional politics based on these understandings” (Heywood and Drake 1997: 3).

In the 1980s and 1990s, third wave feminists took up activism in a number of forms. Beginning in the mid 1980s, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) began organizing to press an unwilling US government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS. In the latter part of the 1980s, a more radical subset of individuals began to articulate a queer politics, explicitly reclaiming a derogatory term often used against gay men and lesbians, and distancing themselves from the gay and lesbian rights movement, which they felt mainly reflected the interests of white, middle-class gay men and lesbians. As discussed at the beginning of this text, queer also described anti-categorical sexualities. The queer turn sought to develop more radical political perspectives and more inclusive sexual cultures and communities, which aimed to welcome and support transgender and gender non-conforming people and people of color. This was motivated by an intersectional critique of the existing hierarchies within sexual liberation movements, which marginalized individuals within already sexually marginalized groups. In this vein, Lisa Duggan (2002) coined the term homonormativity, which describes the normalization and depoliticization of gay men and lesbians through their assimilation into capitalist economic systems and domesticity—individuals who were previously constructed as “other.” These individuals thus gained entrance into social life at the expense and continued marginalization of queers who were non-white, disabled, trans, single or non-monogamous, middle-class, or non-western. Critiques of homonormativity were also critiques of gay identity politics, which left out concerns of many gay individuals who were marginalized within gay groups. Akin to homonormativity, Jasbir Puar coined the term homonationalism, which describes the white nationalism taken up by queers, which sustains racist and xenophobic discourses by constructing immigrants, especially Muslims, as homophobic (Puar 2007). Identity politics refers to organizing politically around the experiences and needs of people who share a particular identity. The move from political association with others who share a particular identity to political association with those who have differing identities, but share similar, but differing experiences of oppression (coalitional politics), can be said to be a defining characteristic of the third wave.

Around the same time as ACT UP was beginning to organize in the mid-1980s, sex-positive feminism came into currency among feminist activists and theorists. Amidst what is known now as the “Feminist Sex Wars” of the 1980s, sex-positive feminists argued that sexual liberation, within a sex-positive culture that values consent between partners, would liberate not only women, but also men. Drawing from a social constructionist perspective, sex-positive feminists such as cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin (1984) argued that no sexual act has an inherent meaning, and that not all sex, or all representations of sex, were inherently degrading to women. In fact, they argued, sexual politics and sexual liberation are key sites of struggle for white women, women of color, gay men, lesbians, queers, and transgender people—groups of people who have historically been stigmatized for their sexual identities or sexual practices. Therefore, a key aspect of queer and feminist subcultures is to create sex-positive spaces and communities that not only valorize sexualities that are often stigmatized in the broader culture, but also place sexual consent at the center of sex-positive spaces and communities. Part of this project of creating sex-positive, feminist and queer spaces is creating media messaging that attempts to both consolidate feminist communities and create knowledge from and for oppressed groups.

In a media-savvy generation, it is not surprising that cultural production is a main avenue of activism taken by contemporary activists. Although some commentators have deemed the third wave to be “post-feminist” or “not feminist” because it often does not utilize the activist forms (e.g., marches, vigils, and policy change) of the second wave movement (Sommers, 1994), the creation of alternative forms of culture in the face of a massive corporate media industry can be understood as quite political. For example, the Riot Grrrl movement, based in the Pacific Northwest of the US in the early 1990s, consisted of do-it-yourself bands predominantly composed of women, the creation of independent record labels, feminist ‘zines, and art. Their lyrics often addressed gendered sexual violence, sexual liberationism, heteronormativity, gender normativity, police brutality, and war. Feminist news websites and magazines have also become important sources of feminist analysis on current events and issues. Magazines such as Bitch and Ms., as well as online blog collectives such as Feministing and the Feminist Wire function as alternative sources of feminist knowledge production. If we consider the creation of lives on our own terms and the struggle for autonomy as fundamental feminist acts of resistance, then creating alternative culture on our own terms should be considered a feminist act of resistance as well.

As we have mentioned earlier, feminist activism and theorizing by people outside the US context has broadened the feminist frameworks for analysis and action. In a world characterized by global capitalism, transnational immigration, and a history of colonialism that has still has effects today, transnational feminism is a body of theory and activism that highlights the connections between sexism, racism, classism, and imperialism. In “Under Western Eyes,” an article by transnational feminist theorist Chandra Talpade Mohanty (1991), Mohanty critiques the way in which much feminist activism and theory has been created from a white, North American standpoint that has often exoticized “3rd world” women or ignored the needs and political situations of women in the Global South. Transnational feminists argue that Western feminist projects to “save” women in another region do not actually liberate these women, since this approach constructs the women as passive victims devoid of agency to save themselves. These “saving” projects are especially problematic when they are accompanied by Western military intervention. For instance, in the war on Afghanistan, begun shortly after 9/11 in 2001, U.S. military leaders and George Bush often claimed to be waging the war to “save” Afghani women from their patriarchal and domineering men. This crucially ignores the role of the West—and the US in particular—in supporting Islamic fundamentalist regimes in the 1980s. Furthermore, it positions women in Afghanistan as passive victims in need of Western intervention—in a way strikingly similar to the victimizing rhetoric often used to talk about “victims” of gendered violence (discussed in an earlier section). Therefore, transnational feminists challenge the notion—held by many feminists in the West—that any area of the world is inherently more patriarchal or sexist than the West because of its culture or religion through arguing that we need to understand how Western imperialism, global capitalism, militarism, sexism, and racism have created conditions of inequality for women around the world.

In conclusion, third wave feminism is a vibrant mix of differing activist and theoretical traditions. Third wave feminism’s insistence on grappling with multiple points-of-view, as well as its persistent refusal to be pinned down as representing just one group of people or one perspective, may be its greatest strong point. Similar to how queer activists and theorists have insisted that “queer” is and should be open-ended and never set to mean one thing, third wave feminism’s complexity, nuance, and adaptability become assets in a world marked by rapidly shifting political situations. The third wave’s insistence on coalitional politics as an alternative to identity-based politics is a crucial project in a world that is marked by fluid, multiple, overlapping inequalities.

Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

LITERATURE

Romanticism

Although the publication of Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads in 1798 is often heralded as the formal start of Romanticism, the roots of the movement began earlier. The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, had embraced the power of rational thought and the scientific method to advance society in an orderly fashion. Romanticism, however, heralded a more individual approach, often guided by strong emotions and some type of spiritual insight. According to Romantics, deeper understanding of the world was achieved through intuition and emotional connections, rather than reason. In literature, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of the early proponents of the Storm and Stress (Sturm und Drang ) period, which rejected the Enlightenment’s focus on reason in favor of strong emotions and the value of the individual. Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) is a classic Storm and Stress novel, with a protagonist driven by his extreme emotions. If nature could be a source for inspired reflection in Wordsworth, it could also be dangerous. Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” which touches on the Romantic idea of poet as genius at the end, notes the thin line between genius and madness. Exceptional individuals as protagonists are the norm in Romanticism, in part from the (early) admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte.

The admiration for Bonaparte, however, began to fade among many Romantic poets as he became a part of the monarchy and a more traditional figure of authority. One type of exceptional individual, the Romantic hero, has either rejected society or been rejected, and therefore is no longer constrained by society’s rules (with the reminder that a Romantic hero is not necessarily romantic, but rather a product of Romanticism). Romantic heroes tend to be self-centered and arrogant, but are capable of compassion and even self-sacrifice, in some cases. A Byronic hero is a subset of Romantic hero, named for the poet Byron, who was described as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The distinction between the two types can get murky, since the Byronic hero is in some ways simply a bit more dangerous and alienated than the Romantic hero (in fact, characters such as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Faust in Goethe’s Faust have been called both by various literary scholars). Byronic heroes are more likely to have some guilty secret in the past, or some unnamed crime that is never revealed, which drives the characters’ actions, and they are more likely to end tragically.

There were critiques of Romanticism even during the movement. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, she questions both Enlightenment views of science and Romanticism’s view of the hero. The first narrator, Robert Walton, fails miserably to advance scientific exploration in the Arctic, while risking the lives of others. Similarly, Victor Frankenstein’s self-absorbed behavior slowly destroys everyone around him. Victor’s passivity and silence become more and more criminal as the novel progresses. Mary Shelley began the novel while she and her future husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, were spending time with Byron, which makes her critical analysis even more intriguing.

Literary movements are, of course, fluid and overlapping. Some scholars date the end of Romanticism to the early 1830s, while others extend Romanticism to as late as 1870. In British literature, Victorianism (1837-1901), which coincides with the reign of Queen Victoria, covers the transition from Romanticism to Realism; while poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are clearly descendants of Romanticism, their work contains realistic elements that do not technically fit into Romanticism.

William Wordsworth

As a young man, Wordsworth memorized passages from Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, and John Milton. His lyrical poetry, therefore, bears the imprint of the musical quality of the early modern poets who lived before him. From Milton’s concept of the sublime, he created work that celebrates the sublimity of the natural world. Wordsworth, who is now considered the premier poet of the Romantic movement, enjoyed most of his acclaim long after his death. During his lifetime, his work was overshadowed by the more immediate popularity of Lords Tennyson and Byron. When the Romantic Movement spread to other parts of Europe and America, however, Wordsworth’s connection of nature and the human imagination sparked an immense following.

Together with Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey, Wordsworth’s literary circle became known as the “Lake Poets,” named after the Lake District in England. In 1798, Wordsworth and Coleridge published their collaboration, Lyrical Ballads, which was popular and brought them some financial success. The book contained one of Wordsworth’s best-known poems, “Tintern Abbey,” the study of a natural location with thematic undertones of loss and consolation. The book also contains one of Coleridge’s famous poems, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Much to the chagrin of the literary establishment, the innovation of Lyrical Ballads influenced a rising, younger group of poets such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats.

In the Preface to the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth proposes a theory that connects poetry and the workings of the human mind. His intended audience is not the high-brow literary elite, but the common men and women. For example, he addresses those who were caught in the industrial confines of cities due to the loss of common land in the country in his poignant poem “Michael.” In the “Preface,” Wordsworth writes, “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility,” an example of which he demonstrates in “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.” Perhaps his most powerful and influential poem, “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” captures the human mind and its connection to the natural world.

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

License: Public Domain

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

and twinkle on the Milky Way,

They stretched in never-ending line

along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

in such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

what wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Coleridge is the first critic of the Romantic literary movement in England. His father was a school-master and a vicar, and Coleridge grew up in a household full of books, which he read voraciously. His father’s fascination with astronomy created in the young man a vision of the vastness of the world, a vision that would later inform his own work. His character and literary style were formed when he was an adolescent student at Christ’s Hospital school in London; there, he immersed himself in the classics and English poets such as Shakespeare and Milton. From the English poets, he drew the significance of sound and imagery. Coleridge saw poetry as a means of enjoyment and science as a means to scientific truth; according to Coleridge, however, the best poetry uses metaphor and imagery to express truth. He is responsible for bringing the ideas of Immanuel Kant and human understanding to the literary circles of England. He also introduces an innovative supernatural context in much of his poetry, which requires that his audience release their grip on reason. He collaborated with William Wordsworth in Lyrical Ballads, a foundational book of verse for the Romantic period. In his Biographia Literaria (1817), Coleridge introduces the concept of a “willing suspension of disbelief”: In this idea originated the plan of the Lyrical Ballads; in which it was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic, yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.

The suspension of disbelief or poetic faith is necessary for the enjoyment of two of Coleridge’s famous poems, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798) and “Kubla Khan” (1817). Coleridge’s “Kubla Kahn” appeared in his imagination in the waking moments of an opium-induced sleep; the poem represents the poet’s fascination with the human imagination and the vastness of nature, the unconscious and fantasy. This poem, though not Coleridge’s most prized work, has stimulated scholarly conversation for its potent and vivid imagery and language, and foreshadows the work of poets like William Blake and the American poet Edgar Allan Poe.

Kubla Khan

License: Public Domain

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

From an early age, Percy Bysshe Shelley was a controversial figure. He was the first-born male of his family, and therefore he had expectations of a substantial family inheritance. He was expelled from Oxford for publishing a pamphlet entitled The Necessity of Atheism (1811), copies of which he sent to every conservative professor at the college. Shelley and his father parted company upon his refusal to accept Christianity as a means of reinstatement to the college, forcing Shelley to wait for two years to receive his inheritance. Shelley would continue to defy religious hypocrisy and espouse politically radical ideas for the rest of his short life. Shelley’s defiance of social traditions extended to his personal life. His first wife, Harriett Westbook, committed suicide when Shelley began an affair with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. The group of radical intellectuals with which Shelley associated touted free love and lived on the fringe of respectable society. Shelley legally married Mary, but continued to have affairs with many women as the couple made their way across Europe. Mary Shelley would later write the Romantic masterpiece Frankenstein. Shelley’s death by drowning in 1822 established him as a tragic figure in the Romantic era. In spite of the few years in which he lived and composed, Shelley leaves behind some of the period’s most elegant poetry. He is buried beside John Keats in Italy. Shelley’s poetry practically trips from the lips in tremendous similes, alliterations, and phrases. In “Ozymandias,” he explains the vanity of greatness in the fall of Ramesses II of Egypt.

Ozymandias

License: Public Domain

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—”Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is best known for her novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818, revised 1831). As the daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and early feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, the expectations for Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin were high. Her mother died shortly after her birth, and her father gave her an unconventional education. Mary grew up listening to her father’s guests, who ranged from scientists and philosophers to literary figures such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Mary was sixteen when she fell in love with one of her father’s admirers, the young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (who was estranged from his wife), and ran away with him. The two of them married, several years later, after the death of Shelley’s first wife. In the summer of 1816, Mary and Percy became the neighbors of Lord Byron, with whom they developed a close friendship while vacationing on the shores of Lake Geneva. During a stretch of bad weather, Byron suggested that each of them should write a ghost story. Mary’s initial idea, which resulted from a nightmare she had, quickly evolved into Frankenstein.

The story of Victor Frankenstein is a cautionary tale of what happens when Romantic ambition and Enlightenment ideals of science and progress are taken too far. This theme also appears in the story of the narrator, the unlucky explorer Robert Walton, who encounters Victor and hears his story. Victor’s most important failure is his abandonment of his Creature, who never receives a name. Victor leaves his initially innocent “child” to survive on his own simply because of his appearance. Although Victor questions whether he himself is to blame for everything that follows, he continues to be repulsed by the Creature’s looks. The impassioned speeches that Mary Shelley writes for the Creature implicitly criticize society for rejecting someone for the wrong reasons. In the end, it is left to the reader to decide whether Victor, the Creature, and/or society in general is the most monstrous.

Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus

Read an excerpt of Frankenstein here

World Literature Copyright © by Anita Turlington; Rhonda Kelley; Matthew Horton; Laura Ng; Kyounghye Kwon; Laura Getty; Karen Dodson; and Douglas Thomson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Realism

The dates for Realism as a movement vary, from as early as 1820 to as late as 1920. Although Realism is, in many ways, a rejection of Romanticism, it does address some of the same concerns about the industrial revolution that Wordsworth had expressed earlier. The passage of years increased the number of authors who noted the failures of industrialization, especially where pollution and quality of life were concerned. The British period of Victorianism (1837-1901) saw a gradual shifting from Romanticism to Realism. Poets such as Tennyson and Robert Browning are more properly transitional poets: products of Romanticism, but who express themselves in more realistic terms. It is important to remember not only that literary movements are not set in stone, but also that they are not always identified the same way by their own time period. When Charles Baudelaire wrote his seminal work, The Flowers of Evil (1857), he was praised as a poet of Romanticism by Gustave Flaubert, even though most modern scholars locate Baudelaire in Realism, and later poets of Modernism cite him as an early example of their own movement.

Romanticism was slowly but surely replaced with an attempt to see the world as it is. As later generations would note, it is difficult to represent reality in its entirety in one poem, play, short story, or novel. Early Realists tended to include more portrayals of middle class and/or lower class characters, who previously were not the main subjects of literature. In Europe, writers such as Ibsen wrote about the middle class specifically, using ordinary occurrences (at least, ordinary for the middle class experience) as the stuff of drama. Authors such as Henry James occasionally were criticized for novels in which very little seems to happen, since ordinary events are rarely as dramatic as the situations regularly found in Romanticism. In some cases, the attempt to be more realistic led to many works that focused on the negative aspects of humans, leaving out the positive aspects to avoid Romantic overtones.

As a general guideline, Realism tended to point out society’s problems (and the problems with the Romantic view), but offered observations, rather than suggested changes. Naturalism, a subset of Realism often treated as a separate movement, was regularly motivated by a desire to improve the world. Naturalism concerned itself with the poorest members of society in particular, and social change was the goal. Naturalism was criticized for being even more focused on the negative aspects of life than regular Realism. Emile Zola’s novel Germinal (1885) is perhaps the most famous example of Naturalism. In it, Zola depicts the lead-up to and aftermath of a coal miners’ strike with a stark realism that shocked readers. His unsentimental portrayal (in almost journalistic fashion) of events angered both conservatives (reluctant to admit the brutal working and living conditions of the poor) and socialists (unhappy that the workers were not Romantic heroes). Eventually, Modernism began in literature as Realism and Naturalism were ending, overlapping for a brief period of time. Perhaps not surprisingly, Modernism would claim to be more real than Realism—or, as the artist Georgia O’Keeffe said, “Nothing is less real than realism” (Haber), preferring abstract art as a way to arrive at a more complete image of (one type of) truth.

Baudelaire

Like the work of so many transitional authors, Charles Baudelaire’s poetry cannot be classified easily. In 1861, Gustave Flaubert wrote a letter to Baudelaire complimenting him on his poetic style: “You have found a way to inject new life into Romanticism. You are unlike anyone else” (Flaubert). Baudelaire is believed to have coined the term “modernity” (modernité), which does not necessarily carry the same connotations as being a modern poet or a product of Modernism, focusing as it does on the urban experience. Nonetheless, Baudelaire was an early inspiration for later Modernist (and Symbolist) poets, even though his poetry is now most often classified as Realism. Baudelaire saw himself as a poet of the urban life in Paris, claiming that beauty can be found in the ugliest images and most depraved situations. His most famous book of poetry, provocatively titled The Flowers of Evil, was published in 1857. Audiences were shocked by Baudelaire’s directness in his poems about sex, death, and depression, to name a few of the topics. Baudelaire, his publisher, and his printer were charged with and found guilty of public indecency, and six of the poems were banned from subsequent editions (the ban on the six poems, which discuss lesbians and vampires, was not lifted in France until 1949). Baudelaire’s life was provocative as well; he cultivated the image of a “cursed poet” (poéte maudit) with a life of drugs, prostitutes, mistresses, and wasteful spending. He squandered roughly half of his inheritance in the first two years, so his family convinced a judge to remove control of his finances and give him an allowance. Despite the many setbacks in his life, Baudelaire’s literary fame grew as time passed. He continued to innovate in his writing, experimenting with prose poetry in his later years. Those poems were published posthumously in Paris Spleen (1869), adding to Baudelaire’s influence on Modernist writers.

Correspondences

License: Public Domain

In Nature’s temple living pillars rise,

And words are murmured none have understood.

And man must wander through a tangled wood

Of symbols watching him with friendly eyes.

As long-drawn echoes heard far-off and dim

Mingle to one deep sound and fade away;

Vast as the night and brilliant as the day,

Colour and sound and perfume speak to him.

Some perfumes are as fragrant as a child,

Sweet as the sound of hautboys, meadow-green;

Others, corrupted, rich, exultant, wild,

Have all the expansion of things infinite:

As amber, incense, musk, and benzoin,

Which sing the sense’s and the soul’s delight.

The Corpse

License: Public Domain

Remember, my Beloved, what thing we met

By the roadside on that sweet summer day;

There on a grassy couch with pebbles set,

A loathsome body lay.

The wanton limbs stiff-stretched into the air,

Steaming with exhalations vile and dank,

In ruthless cynic fashion had laid bare

The swollen side and flank.

On this decay the sun shone hot from heaven

As though with chemic heat to broil and burn,

And unto Nature all that she had given

A hundredfold return.

The sky smiled down upon the horror there

As on a flower that opens to the day;

So awful an infection smote the air,

Almost you swooned away.

The swarming flies hummed on the putrid side,

Whence poured the maggots in a darkling stream,

That ran along these tatters of life’s pride

With a liquescent gleam.

And like a wave the maggots rose and fell,

The murmuring flies swirled round in busy strife:

It seemed as though a vague breath came to swell

And multiply with life

The hideous corpse. From all this living world

A music as of wind and water ran,

Or as of grain in rhythmic motion swirled

By the swift winnower’s fan.

And then the vague forms like a dream died out,

Or like some distant scene that slowly falls

Upon the artist’s canvas, that with doubt

He only half recalls.

A homeless dog behind the boulders lay

And watched us both with angry eyes forlorn,

Waiting a chance to come and take away

The morsel she had torn.

And you, even you, will be like this drear thing,

A vile infection man may not endure;

Star that I yearn to! Sun that lights my spring!

O passionate and pure!

Yes, such will you be, Queen of every grace!

When the last sacramental words are said;

And beneath grass and flowers that lovely face

Moulders among the dead.

Then, O Beloved, whisper to the worm

That crawls up to devour you with a kiss,

That I still guard in memory the dear form

Of love that comes to this!

Spleen

License: Public Domain

The rainy moon of all the world is weary,

And from its urn a gloomy cold pours down,

Upon the pallid inmates of the mortuary,

And on the neighbouring outskirts of the town.

My wasted cat, in searching for a litter,

Bestirs its mangy paws from post to post;

(A poet’s soul that wanders in the gutter,

With the jaded voice of a shiv’ring ghost).

The smoking pine-log, while the drone laments,

Accompanies the wheezy pendulum,

The while amidst a haze of dirty scents,

—Those fatal remnants of a sick man’s room—

The gallant knave of hearts and queen of spades

Relate their ancient amorous escapades.

Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert was born on Dec. 12, 1821 in Rouen, France. He grew up in an affluent middle class family; his father was a respected surgeon. As a young man, Flaubert became friends in college with other students who despised the bourgeoisie, and began writing short stories and, eventually, novels that were critical of middle class values. Flaubert’s health problems (he suffered from epilepsy) forced him to give up plans to study the law, so he devoted his energies to writing literature. After his father died, he retired to a country house near Rouen, where he would spend the rest of his life. His masterpiece, Madame Bovary, is a psychological study of a woman desperate to escape a banal middle-class life. Flaubert is considered to be one of the greatest practitioners of literary realism in France. “A Simple Soul” is the study of the life of Felicite, a servant of Madame Aubain. Over the course of 50 years, she loses many people for whom she cares, and she ends her life caring for a rather difficult parrot named Loulou.

Consider while reading:

- What characteristics of realism do you see in this story?

- Analyze the character of Felicite. What kind of suffering and loss does she undergo in her life?

- What do you think Flaubert is saying about life through this character. How do you respond to her?

- What is the significance of the title of the short story?

Read an excerpt of “A Simple Soul” here: A Simple Soul – Gustave Flaubert – World Literature (nvcc.edu)

Christina Rossetti

Christina Rossetti was born the youngest child in a famous and accomplished family of artists, poets and scholars. Educated at home, she was by nature reserved and pious, like her mother. A devout evangelical Christian, she rejected suitors she considered not sufficiently serious in their faith. She suffered from neuralgia and angina for much of her life and lived very quietly, working for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and writing mostly devotional poetry. The long poem “Goblin Market” (1862) is Rossetti’s best known work and is markedly different in style and content from any of her other poems. Published in 1862 and illustrated by her brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the well-known Pre-Raphael poet, the poem was controversial from the first. While she informed her publisher that the poem was not intended for children, Rossetti often insisted in public that it was intended for children. The plot of the long narrative poem is very similar to a fairy tale: the brave and steadfast sister, Lizzie, saves her impulsive sister Laura from a deadly enchantment that has resulted from Laura succumbing to the temptation of eating goblin fruit. The poem’s dark undertones of sexuality, commodification, and religious ritual have fascinated readers since its publication.

After Death

License: Public Domain

The curtains were half drawn, the floor was swept

And strewn with rushes, rosemary and may

Lay thick upon the bed on which I lay,

Where through the lattice ivy-shadows crept.

He leaned above me, thinking that I slept

And could not hear him; but I heard him say:

“Poor child, poor child”: and as he turned away

Came a deep silence, and I knew he wept.

He did not touch the shroud, or raise the fold

That hid my face, or take my hand in his,

Or ruffle the smooth pillows for my head:

He did not love me living; but once dead

He pitied me; and very sweet it is

To know he still is warm though I am cold.

Up-Hill

License: Public Domain

Does the road wind up-hill all the way?

Yes, to the very end.

Will the day’s journey take the whole long day?

From morn to night, my friend.

But is there for the night a resting-place?

A roof for when the slow dark hours begin.

May not the darkness hide it from my face?

You cannot miss that inn.

Shall I meet other wayfarers at night?

Those who have gone before.

Then must I knock, or call when just in sight?

They will not keep you standing at that door.

Shall I find comfort, travel-sore and weak?

Of labor you shall find the sum.

Will there be beds for me and all who seek?

Yea, beds for all who come.

Leo Tolstoy

This Russian writer was born in a privileged class and chose to abandon his privilege for a simple life. Beloved for the radical transformation in his work and in his life, he has become one of the most famous writers in literature. His writing reflects his life, in fact, in its simplicity and realism. As a young man in school, Tolstoy excelled in linguistics, and he master several languages. When he traveled through Europe, therefore, he was able to absorb the political and social climate through conversations with the common people he met. At home in Russia, Tolstoy sympathized with the serfs, who bore the brunt of fierce poverty brought about by war and famine. His experience in the Crimean War led to his great novel War and Peace (1869), a realistic and gruesome account of battle. Another of his great novels, Anna Karenina (1873-77), introduces the audience to the reality of relationship among corrupt human beings. Tolstoy continually treats realism as a means of admonishing others to moral righteousness.

In his mid-50’s, Tolstoy experienced a religious conversion that led to his abandoning the Russian Orthodox Church in favor of the simple faith and a purer form of Christianity. Instead of living in his estate house, he lived and worked alongside the peasants, worshipping with them instead of observing religious ritual. Of course, he was consequently excommunicated from the Orthodox Church. His change of lifestyle, however, endeared him to a wide audience in both Russia and Europe. He professed a religious system in which human beings are born pure, but are eventually and inevitably corrupted by society. His characters search for happiness in social success, but they only find peace in an objective and realistic acceptance of life. Tolstoy also became interested in educational theory; subsequently, he opened a school in his family manor house for the children of the country peasants who worked the land. He taught a method of inspiration that influenced educators in Europe and America, who modeled Tolstoy’s approach to learning in the early stages of public educational.

Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) demonstrates the self-centeredness and shallowness of people in high society. Ilyich makes all the right moves to gain wealth and social acceptance: he marries a well-connected woman he does not really love; he neglects his wife and children in favor of his career; and, as a judge, he treats the prisoners in his court with disdain and indifference. When Ilyich must come to terms with the reality of death, he learns that the only comfort he receives is from a servant who represents the naturalness of the common people.

Consider while reading:

- Describe Ivan Ilyich’s wife’s reaction to his illness and death.

- Describe his associates’ reactions to his death.

- What is the significance of the black bag?

- How does Ilyich finally let go of life and embrace death?

Read The Death of Ivan Ilyich here: The Death of Ivan Ilych – Leo Tolstoy – World Literature (nvcc.edu)

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s life was every bit as eventful as the stories that he wrote. As a young man, he was sentenced to be executed by a firing squad for being part of a group that was considered subversive. He received a last-minute reprieve from the tsar, and Dostoyevsky instead spent four years doing hard labor in a Siberian prison camp. Those experiences informed his works; in addition to characters who face imminent death or time in Siberia, there are characters with epilepsy, gambling problems, bad luck in love, and ongoing poverty—all conditions that he faced. His fame began with his first novella, Poor Folk (1845), but he never made enough money from his writings to support his family in comfort. Despite all of these hardships, Dostoyevsky managed to become one of Russia’s greatest writers. Leo Tolstoy praised Dostoyevsky as the better writer, and his works influenced writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Jean-Paul Sartre, and William Faulkner, among many others (including Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud). Dostoyevsky is considered the first existentialist novelist; for him, the psychology of the characters is the basis for realism (their experience of the world is the world). In novels such as Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880), characters range from murderers to devout followers of the Russian Orthodox Church (Dostoyevsky’s own religious preference), all portrayed with psychological clarity. In Notes from Underground (1864), Dostoyevsky satirizes (among other things) the idea that scientific progress will create a utopian society. In Part One, the unnamed narrator, or Underground Man, may seem crazy at first, with what appear to be random and contradictory thoughts. In fact, the argument is constructed very carefully to demonstrate that human beings demand free will—and that they will give up everything to get it. In Part Two, which is an extended flashback, the Underground Man offers a practical demonstration of his theories in his own past. Of particular interest is his love-hate relationship with Romanticism; the narrator ultimately argues that all of us prefer Romanticism to real life (or Realism), simply because real life is not as satisfying as escapism.

Read “Notes From Underground” here: Notes from Underground – Fyodor Dostoyevsky – World Literature (nvcc.edu)

Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Ibsen is called both “the father of Realism” and “the father of modern theater” in Europe, which is to say that he was the first playwright to use Realism on stage. Ibsen’s impact on theater makes him the most influential European playwright since Shakespeare. For Ibsen, art should be both challenging and a force for social change; his plays often expose what he saw as the moral hypocrisy of society. In particular, Ibsen’s plays peel back the veneer of respectability of the Norwegian middle class, revealing what happens when people only pretend to be moral. No group or ideology was safe from his criticism, and often there are no characters in a play who are completely without blame. For example, in An Enemy of the People (1882), the outright villains may be the businessmen who are poisoning the local water source, but the locals are equally at fault for refusing to believe the truth for selfish reasons, and the supposed hero of the story makes matters worse with his stubborn temper. In Ghosts (1881), Ibsen broke several taboos in his depiction of how a husband’s repeated infidelities lead to passing on syphilis to his unborn son. As guilty as the husband was, everyone from the pastor to the wife bear some responsibility for looking the other way, even after the husband’s death. Ibsen’s goals for A Doll’s House (1879) are every bit as broad as his other works. Nora and Torvald try to live up to their society’s ideals for how men and women should behave, but both of them become victims to society’s unrealistic expectations. The truth in this case is a lit match that leads to a metaphorical explosion. The fact that Nora and Torvald do not agree on the definition of what is right appears to be a product of which gender holds the power in society, rather than an actual gender issue. A Doll’s House does not offer a conventional happy ending, which so shocked audiences that some theaters actually rewrote the ending when staging it. The ending is also complicated by the fact that Nora’s rebellion against expectations has no guarantee of success in a society where women could not even borrow money without a man’s signature. A common theme in Ibsen’s plays, therefore, is that truth does not always set you free; in fact, sometimes the very best intentions are doomed to failure if society refuses to listen or change. It is a problem that Ibsen faced himself, since his efforts to influence change were invariably seen as shocking and controversial. It is a testament to his persistence and talent that audiences now expect the theater to address social issues.

Read A Doll’s House here: #10 – A doll’s house : Ghosts / With an introd. by William Archer – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library

H.G. Wells

Herbert George Wells, generally referred to as H.G. Wells, was a prolific 19th-century British writer best known for his science fiction novels. He is often referred to, in fact, as the father of science fiction. Born into a lower middle class family, after his father’s shop failed and the family went bankrupt, Wells held a variety of jobs as an adolescent, including working as a teaching assistant, apprentice draper, and pharmacy clerk. He would later use these experiences in his novels as the basis for social satire. After eventually winning a scholarship to Imperial College, Wells trained as a scientist; he was particularly interested in Darwinian theory. Wells was also an avid Socialist and an active member of the Fabian Society, an organization that advocated a long-term approach to the eventual Socialist revolution. Throughout his life, Wells suffered from various physical ailments, including diabetes, and his life was further complicated by a series of romantic affairs and two failed marriages. Wells, who published 51 novels as well as dozens of stories, story collections, works of non-fiction, and essays, is also best known for his novels The Time Machine, War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man, and When the Sleeper Awakes. An early science fiction novel, The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) dramatizes the practice of vivisection, the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of scientific research. Vivisection was a controversial topic in fin de siècle England, with a number of organizations formed to fight the practice as cruel and unethical. As the novel examines the ethics of vivisection, it also illustrates the possibility that civilization was spiraling downward into an increasingly degenerate state. Although Wells was an educated man and a scientist, he appears to be warning of the dangers that unregulated science can pose to the larger community.

Read The Island of Dr. Moreau here: The Island of Doctor Moreau – H.G. Wells – World Literature (nvcc.edu)

W.B. Yeats

The poetry of William Butler Yeats does not fit easily into any literary movement. He admired the Victorian Pre-Raphaelites, who embraced a combination of realistic techniques and symbolic meanings. Yeats’ poetry is full of myths and symbols, and his belief in a type of mysticism or spiritualism underlies much of his work (for Yeats, mysticism and the occult were real, not metaphorical). His earlier poems, such as “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (1890), could be straight out of Victorianism, but over time, Yeats began to incorporate more realistic elements into his poetry. In “Easter, 1916″—written right after the failed Easter Uprising for Irish independence—Yeats offers a critical (and mostly unflattering) view of the individuals who were executed, but recognizes how their deaths for the cause have transformed them into something greater than themselves (a new mythology). Despite that transformation, the narrator worries about whether it was a worthwhile sacrifice (in fact, by 1922, Yeats would be elected a senator in the new Republic of Ireland). Even though his poetry in later years would contain elements of Modernism, such as in the poem “The Second Coming” (1921), Yeats never abandoned the mystical and symbolic in his poetry, becoming a modern poet who disliked Modernism and refused to give up traditional elements (Albrecht; Longley). In his life, Yeats had the same tendency to be caught between (or among) movements. Although he was an Anglo-Irish Protestant born in Dublin, who was expected to support the English presence in Ireland, Yeats became an Irish Nationalist: partly out of patriotism, and partly because he fell in love with the actress Maud Gonne, a beautiful Nationalist. Yeats proposed to Gonne at least four times, and his (bitter) reaction to her rejection of him can be found in many poems, including some of those written after he married Georgiana Hyde-Lees, with whom he had two children. The poem “When You Are Old” (1895) is an early example of his obsession with Gonne. Besides writing poetry, Yeats was one of the founders of the Irish (now Abbey) Theater, for which he wrote many plays. When he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923, it was mostly for his plays, which the Nobel organization noted in 1969 is doubly ironic: not only are his poems more famous now, but also “Yeats is one of the few writers whose greatest works were written after the award of the Nobel Prize” (Frenz).

Easter 1916

License: Public Domain

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our winged horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashed within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse –

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

When You Are Old

License: Public Domain

When you are old and gray and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty will love false or true;

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face.

And bending down beside the glowing bars

Murmur, a little sadly, how love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

License: Public Domain

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements gray,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Modernism