40 EUROPE

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

- Italian Renaissance

- How to recognize Italian Renaissance Art

- Understanding Linear Perpsective

- Masaccio, Holy Trinity

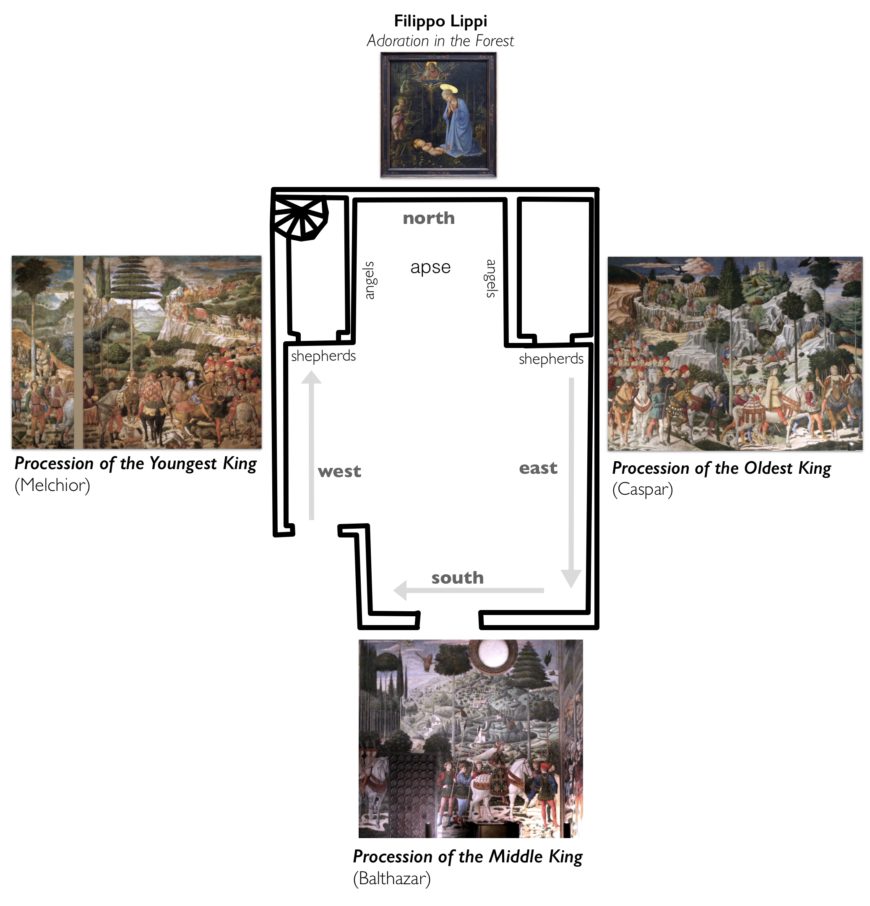

- Benozzo Gozzoli, The Medici Palace Chapel frescoes

- Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus

- Donatello, David

- Donatello, Saint George

- Leonardo and his drawings

- Leonardo, Last Supper

- Leonard, Mona Lisa

- Michelangelo, David

- Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

- Michelangelo, The Last Judgement

- Raphael, School of Athens

- What is Mannerism?

- Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck

- El Greco, View of Toledo

- Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the Head of Medusa

- Michelangelo, Pieta

- Michelangelo, David

- Northern Renaissance

- Introducing the Northern Renaissance

- Workshop of Robert Campin

- Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait

- Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel

- Albrecht Durer, Self-Portrait (1498)

- Albrecht Durer, Melancolia

- Albrecht Durer’s woodcuts and engravings

- Mattias Grunewald, Isenheim Altarpiece

- Han Holbein, The Ambassadors

- Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Mary Tudor

- Portraits of Elizabeth I

- Baroque Art

- Introduction to Baroque Art

- Bian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

- Caravaggio, Calling of St. Matthew

- Artemesia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes

- Diego Velazquez, Las Meninas

- Anthony Van Dyck, Samson and Delilah

- Rembrandt, The Night Watch

- Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait

- Symbolism and meaning in Dutch Still Life Painting

- Willem Kalf, Still Life with a Silver Ewer

- Johannes Vermeer, The Glass of Wine

- Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego

- Rococo Art

- Hyacinth Rigaud, Louis XIV

- Francois Boucher, Madame de Pompadour

- Jean-Honore Fragonard, The Swing

- William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode

- Thomas Gainsborough, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

- Neoclassical Art

- Introduction to Neoclassical Art

- Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii

- Jacques-Louis David, Death of Marat

- Italian Renaissance

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

The Renaissance

The fall of Constantinople was lamented in Europe as signaling that no significant force remained to counter the Muslim advance westward. For many historians, it also marks the end of the European Middle Ages. As the Byzantine Empire collapsed, many Greeks sought refuge in other lands, often wealthy merchants and state officials who brought their riches with them. Many settled in Italy, especially in Venice and Rome. Those who came to Venice were assisted by Anna Notaras, a wealthy Byzantine noblewoman who had taken up residence in the city before Constantinople fell.

Byzantine scholars, theologians, artists, writers, and astronomers also fled westward to Europe, bringing with them the knowledge of ancient Greece and Rome that had been preserved in the eastern half of the Roman Empire after the western half fell. Among the texts they brought were the complete works of Plato and copies of Aristotle’s works in the original Greek. Access to these and other writings, many of which had been either unknown in western Europe or known only in the form of Arabic translations that arrived at the time of the Crusades, greatly influenced the course of the Italian Renaissance.

The Renaissance, which means “rebirth” in French, was a period of intellectual and artistic renewal inspired by the cultural achievements of ancient Greece and Rome and marking the dawn of the early modern world. It began in the city-states of northern Italy that had grown wealthy through trade, especially trade with the Ottomans. Beginning in the 1300s, scholars there turned to the works of Western antiquity—the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans—for wisdom and a model of how to live (Figure 17.15). Among these scholars was Petrarch, who encouraged writers to adopt the “pure” Classical Latin in which the poets and lawmakers of the Roman Empire had written instead of the form of Latin used by medieval clergy. He advocated imitating the style of the Roman orator Cicero and the foremost of the Roman poets, Virgil.

Before the arrival of Byzantine scholars and their copies of Plato and Aristotle, Italian humanists had focused primarily on the study of rhetoric and ethics. They displayed little interest in metaphysics, the philosophical study of the nature of existence. Access to Plato’s complete works changed that, and many scholars were influenced by Byzantine Neoplatonism, an intellectual movement that sought to synthesize the ideas of Plato, Aristotle, the Stoic philosophers, and Arabic philosophy. One of the most important of the Italian Neoplatonists was Marsilio Ficino, who translated all of Plato’s works from ancient Greek to Latin and synthesized Platonic thought with the teachings of Christianity.

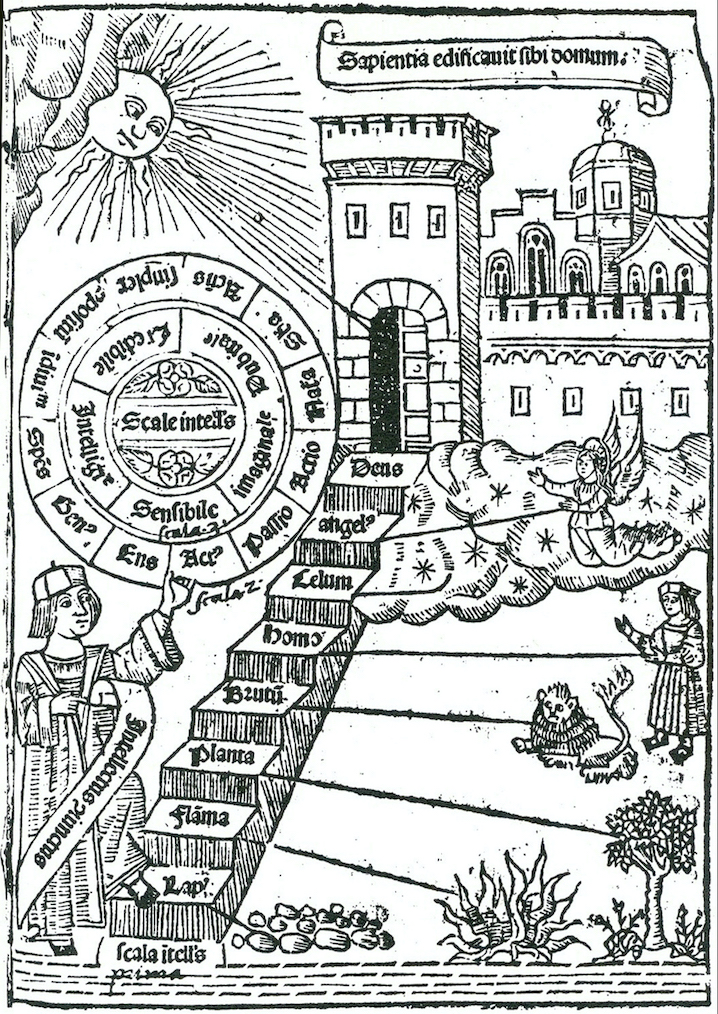

In the Neoplatonic conception, the universe was an ordered hierarchy with God, “the One,” at the top, and everything else existing as “emanations” of God at descending levels with the earth at the bottom. If God was perfect, the physical world in which humans lived was least perfect. However, Ficino argued, the human soul existed at the center of the universe, because it combined aspects of both the godly world and the physical world in which humans lived. Because humans possessed a soul, they were thus the center of creation. Ficino’s ideas fit well with the humanist perception of human beings as special creatures and worthy of study.

Another Neoplatonist, Nicholas of Cusa (Nicholas Cusanus), also had a profound effect on the Italian Renaissance and one of its most important legacies, the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Greek philosopher Aristotle had stressed the study of the world through direct observation, a method known as empiricism. For Plato, however, the world of ideas, of abstract concepts, was superior to the components of the physical world. Thus, mathematical thought was superior to sensory observation as a way of arriving at ultimate knowledge of the “truth” of the world. Nicholas also stressed that mathematical knowledge of the world was superior to knowledge derived from mere observation. He went so far as to state that through mathematics, humans could know the very mind of God.

The idea that the physical world could best be understood through mathematical formulas was espoused by Johannes Kepler, the German astronomer who believed the model of the universe that made the most sense mathematically was the true model. It was through mathematics that Kepler discovered three of the laws of planetary motion and was able to explain how the planets moved in the heliocentric, or sun-centered, model of the universe earlier proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus (Figure 17.17). This was the same view of the universe held by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei: the true nature of the universe could be discovered only through mathematics.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Humanism

Humanism was the educational and intellectual program of the Renaissance. Grounded in Latin and Greek literature, it developed first in Italy in the middle of the fourteenth century and then spread to the rest of Europe by the late fifteenth century. This program, called the studia humanitatis, or the humanities, was thought to teach citizens the morals necessary to lead an active, virtuous life, which its proponents contrasted with the contemplative life of ascetic monks and scholars. As a product of the Italian city-state republics, humanism was a system born in the city and made for the citizen. Although scholars in earlier centuries had embraced classical learning, humanists rediscovered many lost texts, read them with a critical and secular eye, and, through them, forged a new mentality that shaped Italian and European society from from approximately the mid-14th to the mid-17th centuries.

Origins

Although humanist ideas had circulated in Italy since the late twelfth century, their main proponent was the Florentine poet, Francesco Petrarch. Born into an exiled family, Petrarch grew up in the French city of Avignon and attended law school in Bologna. Inspired by his love of antiquity and the Latin writings of Cicero, Petrarch rejected the legal profession to pursue the life of a poet and collector of ancient texts. He spent much of his free time hunting for lost and neglected works of classical authors and twice found major caches of Cicero’s writing, most notably an unknown collection of Cicero’s letters, the Epistolae ad Atticum, in the chapter library of the Verona Cathedral in 1345. He copied the manuscript in the library and soon circulated it among his friends and associates. By the fifteenth century, through the efforts of Petrarch and his followers, Cicero’s taut, philosophical style of writing became the standard in Latin prose.

Through these letters and other ancient texts, Petrarch was able to enter the Roman world so distant to him. Petrarch was the first scholar to recognize the cultural gap between his own age and Cicero’s. Of course, previous scholars throughout the middle ages made use of classical literature, but they read these texts through strict religious lenses and saw themselves inhabiting the same culture as Julius Caesar and emperor Augustus. It was just a world grown old and ruined by time. Petrarch, with his historical consciousness, recognized that he and his fellow Italians were living in a world starkly different from their Roman ancestors with a different set of values. Petrarch advocated reading Cicero and other Roman authors as a means of finding models for eloquence and exemplary comportment.

To highlight this cultural gap between ancient Rome and fourteenth-century Italy, Petrarch envisioned a new way of conceptualizing the past. He portrayed antiquity as a golden age, replete with virtuous men, great deeds, and good morals. It was the period from the fall of Rome right up to his own age that was, to his thinking, the dark age. Indeed, Petrarch coined the term “medio evo” (middle ages) to connote the decline of Roman values, letters, and arts. Petrarch greatly exaggerated the decline of culture in the middle ages with its towering cathedrals and innovations in trade, science, and theology. Regardless, Petrarch pictured his age as a rinascita (rebirth) of classical learning and culture, and created an image of the middle ages as dark and ignorant—an idea that still persists (problematically) to this day.

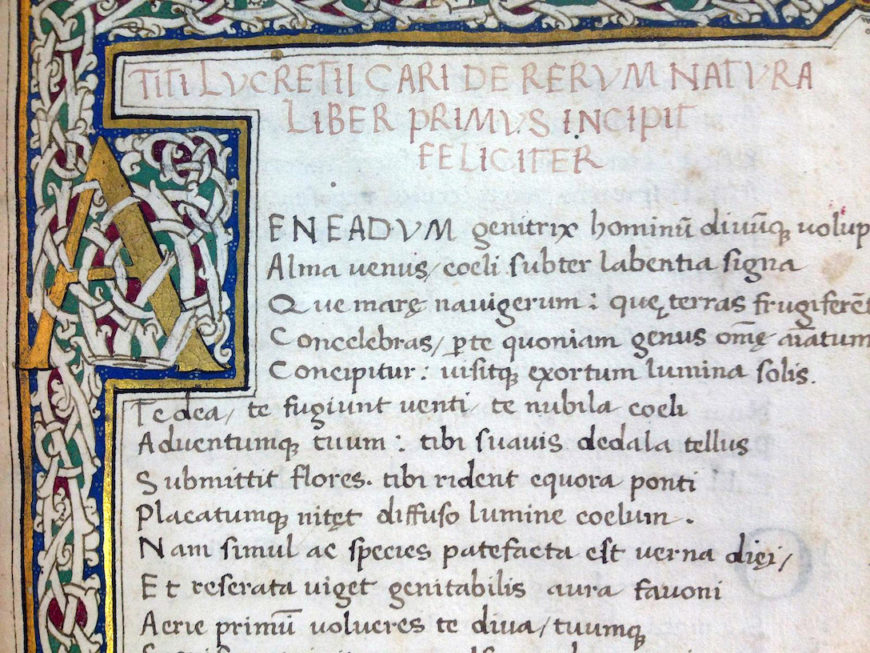

Petrarch’s tolling of the bell to revive Roman antiquity reached appreciative ears. By the early fifteenth century, humanists actively scoured dusty monastic libraries in Italy, France, and Germany, finding more letters of Cicero, Lucretius’s Epicurean poem, On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura), and a host of other ancient texts. Greek scholars, fleeing from the Ottoman attacks on the Byzantine Empire, brought Homer, Plato, Sophocles, and other Greek manuscripts to Italy, as well as taught ancient Greek to a generation of humanists, hungry for learning and for a connection with antiquity.

Who were the humanists?

Humanists were a diverse group as individuals but shared a common passion for antiquity and for Latin prose and rhetoric. Most humanists came from relatively well-heeled backgrounds—they were sons of noblemen, patricians, merchants, and notaries. Many patrician women, like Laura Cereta and Isotta Nogarola, were able to acquire a humanist education and take part in the intellectual life of the renaissance, but moralists frequently discouraged them from pursuing the active life of a teacher, professor, or writer. Nogarola, a writer from Verona, had acquired an education in the studia humanitatis and entered into debates on the role of women in Renaissance society with male humanists. Due to the hostile reception of her activity in humanist circles that questioned her chastity, she retired from the public, never married, and concentrated on sacred literature rather than secular writings. Patrician and noble women, however, often expressed their humanist interests by commissioning works of arts inspired by the classical tradition. Isabella d’Este, the Marquise of Mantua, gained fame as a patron of such Renaissance painters as Giovanni Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, and Pietro Perugino.

However, many humanists came from humbler backgrounds but managed to obtain their education through patronage, natural talent, and hard work. Indeed, humanists were the first western scholars to argue for a nobility of spirit, based on merit and skill, rather than a nobility of blood, based on lineage and ancestry. Most humanists found work as professors, librarians, and secretaries for princes and state chanceries. The prime goal of most humanists was to find a patron willing to support their intellectual activities. Petrarch was able to retire in a villa in the Euganean Hills thanks to patronage from the Carrara despots of Padua. Cosimo de’ Medici allowed Marsilio Ficino the use of his villa in Careggi as a writing retreat. With secure positions, humanists could complete their work in exchange for writing poems, orations, and histories that extolled the virtue, power, and magnanimity of their patrons. For every Petrarch and Ficino, whose fame and learning attracted patrons, there were probably ten humanists who had to scrape by as tutors or secondary-school teachers.

The humanist agenda

Humanists sought to rediscover lost and forgotten texts, purge them of mistakes made by monastic scribes through a rigorous philological analysis, and circulate them in handwritten copies (later, with the advent of the printing press, humanists began to publish printed versions of these texts). In the mid-fifteenth century, after the introduction of Greek texts into Italy due to Ottoman attacks on the Byzantine Empire, humanists translated these texts into Latin, making them more accessible to those who could not read Greek. They often made copious annotations in these manuscripts to help the reader understand them. Moreover, they often published their own works which consciously emulated the style and substance of the ancient authors.

At their core, humanists were educators. They devised their educational program, the studia humanitatis, in complete opposition to the Scholastic tradition (based on logic and theology) that had gained prominence in the middle ages. Humanists wanted a curriculum that would not make theologians but make citizens useful to governments and society. They placed five disciplines in the curriculum of the studia humanitatis: grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history. Each of these disciplines served a specific purpose in fostering virtuous, active citizens of the city-states. These subjects, based on reading Latin (and, later, Greek) authors was to arm citizens with the eloquence, morality, and examples of virtuous behavior of the ancients. The values of the ancient Romans and Greeks would perfect citizens and help them realize their potential as individuals endowed with free will to know the good and to act on it.

Like Plato and other ancient philosophers that preceded them, the humanists aspired to have princes implement their ideas of moral reform. Many, like Leon Battista Alberti, had grand visions of city-planning, which only a prince or a government could execute. Humanists also sought to change Italian society at the individual level by creating uomini universali—well-rounded men who could be useful to society.

Although having diverse views on philosophical matters, humanists were united by a secular view of humanity’s place in the world. They gave orations on and debated the idea of the dignity of man. This concept gained momentum with the revival of Neoplatonism after Marsilio Ficino’s translation of the entire corpus of Plato’s extant works in 1469 and his harmonizing of Christian theology with Platonic ideas.

Ficino’s pupil, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, took this idea further in his Oration on the Dignity of Man, written in 1486. Pico argued that in the chain of being humans occupied a privileged space due their capacity to learn and grow as individuals. They were the median between God and animal and plant life; and they could become “terrestrial gods” due to this thirst for knowledge or stagnate from ignorance. Human dignity lay in this free will—humans could choose where they stood in the chain of being and played a role in shaping themselves and the world.

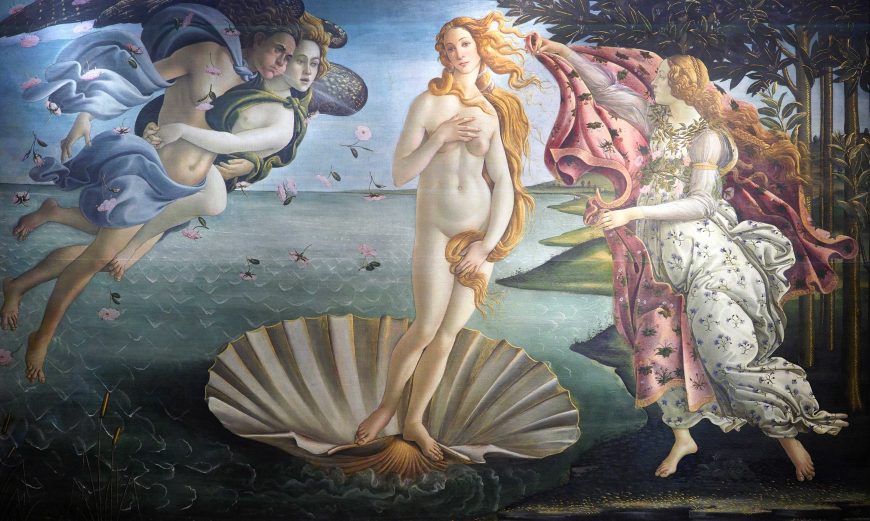

Moreover, humanists not only praised human dignity but also the human body. Rather than being something to hide and be ashamed of, humanists and artists of the renaissance began to depict for the first time since antiquity favorable images of the nude human body, and on a large scale not seen since antiquity. For instance, Venus was portrayed in her classical pose, the Venus pudica—naked but modestly covering her nudity with her arms and long hair rather than as a fully clothed aristocratic woman, as medieval artists had portrayed the goddess. The motif of the Venus pudica is best represented by Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, commissioned by the Medici family in the early 1480s. Even biblical figures could be portrayed in their human nakedness. Nothing like this was possible before 1400 since medieval moralists had nothing but contempt for the human body, seeing it as a receptacle of sin and generally depicted it negatively.

Copyright: Dr. John M. Hunt, “Humanism in renaissance Italy,” in Smarthistory, August 1, 2021, accessed June 13, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/humanism-renaissance-italy/.

Protestantism

The Church and the state

So, if we go back to the year 1500, the Church (what we now call the Roman Catholic Church) was very powerful (politically and spiritually) in Western Europe (and in fact ruled over significant territory in Italy called the Papal States). But there were other political forces at work too. There was the Holy Roman Empire (largely made up of German speaking regions ruled by princes, dukes and electors), the Italian city-states, England, as well as the increasingly unified nation states of France and Spain (among others). The power of the rulers of these areas had increased in the previous century and many were anxious to take the opportunity offered by the Reformation to weaken the power of the papacy (the office of the Pope) and increase their own power in relation to the Church in Rome and other rulers.

Keep in mind too, that for some time the Church had been seen as an institution plagued by internal power struggles (at one point in the late 1300s and 1400s church was ruled by three Popes simultaneously). Popes and Cardinals often lived more like kings than spiritual leaders. Popes claimed temporal (political) as well as spiritual power. They commanded armies, made political alliances and enemies, and, sometimes, even waged war. Simony (the selling of Church offices) and nepotism (favoritism based on family relationships) were rampant. Clearly, if the Pope was concentrating on these worldly issues, there wasn’t as much time left for caring for the souls of the faithful. The corruption of the Church was well known, and several attempts had been made to reform the Church (notably by John Wyclif and Jan Hus), but none of these efforts successfully challenged Church practice until Martin Luther’s actions in the early 1500s.

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German monk and Professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg. Luther sparked the Reformation in 1517 by posting, at least according to tradition, his “95 Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany – these theses were a list of statements that expressed Luther’s concerns about certain Church practices – largely the sale of indulgences, but they were based on Luther’s deeper concerns with Church doctrine. Before we go on, notice that the word Protestant contains the word “protest” and that reformation contains the word “reform” – this was an effort, at least at first, to protest some practices of the Catholic Church and to reform that Church,.

Indulgences

The sale of indulgences was a practice where the church acknowledged a donation or other charitable work with a piece of paper (an indulgence), that certified that your soul would enter heaven more quickly by reducing your time in purgatory. If you committed no serious sins that guaranteed your place in hell, and you died before repenting and atoning for all of your sins, then your soul went to Purgatory – a kind of way-station where you finished atoning for your sins before being allowed to enter heaven.

Pope Leo X had granted indulgences to raise money for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. These indulgences were being sold by Johann Tetzel not far from Wittenberg, where Luther was Professor of Theology. Luther was gravely concerned about the way in which getting into heaven was connected with a financial transaction. But the sale of indulgences was not Luther’s only disagreement with the institution of the Church.

Faith alone

Martin Luther was very devout and had experienced a spiritual crisis. He concluded that no matter how “good” he tried to be, no matter how he tried to stay away from sin, he still found himself having sinful thoughts. He was fearful that no matter how many good works he did, he could never do enough to earn his place in heaven (remember that, according to the Catholic Church, doing good works, for example commissioning works of art for the Church, helped one gain entrance to heaven). This was a profound recognition of the inescapable sinfulness of the human condition. After all, no matter how kind and good we try to be, we all find ourselves having thoughts which are unkind and sometimes much worse. Luther found a way out of this problem when he read St. Paul, who wrote “The just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17). Luther understood this to mean that those who go to heaven (the just) will get there by faith alone – not by doing good works. In other words, God’s grace is something freely given to human beings, not something we can earn. For the Catholic Church on the other hand, human beings, through good works, had some agency in their salvation.

Scripture alone

Luther (and other reformers) turned to the Bible as the only reliable source of instruction (as opposed to the teachings of the Church). The invention of the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century (by Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany) together with the translation of the Bible into the vernacular (the common languages of French, Italian, German, English, etc.) meant that it was possible for those that could read to learn directly from Bible without having to rely on a priest or other church officials. Before this time, the Bible was available in Latin, the ancient language of Rome spoken chiefly by the clergy. Before the printing press, books were handmade and extremely expensive. The invention of the printing press and the translation of the bible into the vernacular meant that for the first time in history, the Bible was available to those outside of the Church. And now, a direct relationship to God, unmediated by the institution of the Catholic Church, was possible.

When Luther and other reformers looked to the words of the Bible (and there were efforts at improving the accuracy of these new translations based on early Greek manuscripts), they found that many of the practices and teachings of the Church about how we achieve salvation didn’t match Christ’s teaching. This included many of the Sacraments, including Holy Communion (also known as the Eucharist). According to the Catholic Church, the miracle of Communion is transubstantiation – when the priest administers the bread and wine, they change (the prefix “trans” means to change) their substance into the body and blood of Christ. Luther denied that anything changed during Holy Communion. Luther thereby challenged one of the central sacraments of the Catholic Church, one of its central miracles, and thereby one of the ways that human beings can achieve grace with God, or salvation.

The Counter-Reformation

The Church initially ignored Martin Luther, but Luther’s ideas (and variations of them, including Calvinism) quickly spread throughout Europe. He was asked to recant (to disavow) his writings at the Diet of Worms (an unfortunate name for a council held by the Holy Roman Emperor in the German city of Worms). When Luther refused, he was excommunicated (in other words, expelled from the church). The Church’s response to the threat from Luther and others during this period is called the Counter-Reformation (“counter” meaning against).

The Council of Trent

In 1545 the Church opened the Council of Trent to deal with the issues raised by Luther. The Council of Trent was an assembly of high officials in the Church who met (on and off for eighteen years) principally in the Northern Italian town of Trent for 25 sessions.

Selected Outcomes of the Council of Trent:

- The Council denied the Lutheran idea of justification by faith. They affirmed, in other words, their Doctrine of Merit, which allows human beings to redeem themselves through Good Works, and through the sacraments.

- They affirmed the existence of Purgatory and the usefulness of prayer and indulgences in shortening a person’s stay in Purgatory.

- They reaffirmed the belief in transubstantiation and the importance of all seven sacraments

- They reaffirmed the authority of both scripture the teachings and traditions of the Church

- They reaffirmed the necessity and correctness of religious art (see below)

The Council of Trent on religious art

At the Council of Trent, the Church also reaffirmed the usefulness of images – but indicated that church officials should be careful to promote the correct use of images and guard against the possibility of idolatry. The council decreed that images are useful “because the honour which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent” (in other words, through the images we honor the holy figures depicted). And they listed another reason images were useful, “because the miracles which God has performed by means of the saints, and their salutary examples, are set before the eyes of the faithful; that so they may give God thanks for those things; may order their own lives and manners in imitation of the saints; and may be excited to adore and love God, and to cultivate piety.”

Violence

The Reformation was a very violent period in Europe, even family members were often pitted against one another in the wars of religion. Each side, both Catholics and Protestants, were often absolutely certain that they were in the right and that the other side was doing the devil’s work.

The artists of this period – Michelangelo in Rome, Titian in Venice, Durer in Nuremberg, Cranach in Saxony – were impacted by these changes since the Church had been the single largest patron for artists. And art was now being scrutinized in an entirely new way. The Catholic Church was looking to see if art communicated the stories of the Bible effectively and clearly (see Veronese’s Feast in the House of Levi for more on this). Protestants on the other hand, for the most part lost the patronage of the Church and religious images (sculptures, paintings, stained glass windows etc) were destroyed in iconoclastic riots.

Other developments

It is also during this period that the Scientific Revolution gained momentum and observation of the natural world replaced religious doctrine as the source of our understanding of the universe and our place in it. Copernicus up-ended the ancient Greek model of the heavens by suggesting that the Sun was at the center of the solar system and that the planets orbited around it.

At the same time, exploration, colonization and (the often forced) Christianization of what Europe called the “new world” continued. By the end of the century, the world of the Europeans was a lot bigger and opinions about that world were more varied and more uncertain than they had been for centuries.

Copyright: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “A-level: The Protestant Reformation,” in Smarthistory, May 23, 2017, accessed June 13, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-protestant-reformation-2/.

Enlightenment

Historians have typically located the birthplace of the Enlightenment in western Europe. Its inspirations were truly global in nature, however, ranging from the cosmopolitanism of the ethnically, religiously, and culturally diverse Ottoman Empire to the rich philosophical traditions of China. Ultimately, these ideas were more influential in Europe than elsewhere, but the consequences of the Enlightenment were by no means limited to Europe. Enlightenment thinkers in Europe created a new synthesis of knowledge that later spread to the rest of the world, where colonial subjects added their own interpretations and put these ideas to their own uses.

Many of the components of Western science that, along with the ideas of the Italian Renaissance, inspired Enlightenment thought were built on scientific traditions developed in the Islamic world, which had absorbed ancient Greek and Indian systems of knowledge. In particular, Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled area of Spain and Portugal that rose to power in 711, began wielding significant influence on European intellectual activity in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. By preserving and translating the works of ancient Greek thinkers, such as Aristotle and Plato, that were not available in Europe at the time, Muslim scholars in Spain fueled both the European Renaissance of the twelfth century and the Italian Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In addition to preserving seminal Greek texts, Muslim scholars in medieval Al-Andalus, such as the twelfth-century intellectual Averroes, also wrote and translated Arabic philosophical treatises that were widely read by scholars in Christian Europe.

Among the principles that influenced Enlightenment perceptions of knowledge were the twin concepts of deductive and inductive reasoning. Inherited from the intellectual framework of the Scientific Revolution, these approaches represent different methods of organizing information and developing hypotheses. While inductive reasoning gathers specific examples and observations to arrive at a broad generalization, deductive reasoning, in contrast, begins with a general statement or theory and applies it to specific conclusions.

Deductive reasoning had its origins in the fourth century BCE in the teachings of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, but it became a vital component of the Scientific Revolution in the work of French philosopher René Descartes. Descartes combined deductive reasoning with empiricism, the acquisition of knowledge from sensory experiences, to establish the foundations of the scientific method. Inductive reasoning, on the other hand, played an important role in the work of the English natural philosopher Francis Bacon. Bacon asserted that whereas the deductive method began with a proposition and discarded evidence that did not support that premise, inductive reasoning reached a conclusion only after the collection of evidence. According to Bacon, only inductive reasoning enabled researchers to support observations with empirical data rather than conjecture.

Ultimately, both inductive and deductive reasoning influenced the intellectual context of the Enlightenment by providing two systematic means of drawing conclusions about the natural world from observations and evidence. Whichever method they adopted, Enlightenment thinkers embraced the scientific method as a means of applying reason and objectivity to the collection and analysis of information.

Natural Rights

The topic of natural rights, rights possessed by all human beings, such as the right to life and liberty, formed the focus of many philosophical treatises and conversations in the eighteenth century. Based on the premise that all people have fundamental and inalienable rights, rights that cannot be revoked or rescinded by human laws, the concept of natural rights originated not in the Enlightenment but in far older traditions of justice and natural law. In the ancient Persian tradition of Zoroastrianism, for example, the concept of asha, meaning “God’s will,” connoted the unchangeable law that emanates from the divine and governs the universe. Although many ancient religious and philosophical traditions developed interpretations of natural law, European Enlightenment thinkers transformed such ideas into a political system, which was novel at the time. The growing emphasis on reason and the desire to improve human life in the eighteenth century led Enlightenment philosophers to envision political systems based on natural rights, rather than the divine right of kings or traditional Christian social hierarchies.

One of the first Enlightenment thinkers to tackle the issue of natural rights was the English philosopher John Locke, who argued that people have fundamental rights to life, liberty, and property. In his influential work of political philosophy, Two Treatises of Government, he argued that all people are born in a state of freedom and that government should exist only by their consent, a principle called popular sovereignty. Although Locke and his European contemporaries asserted the inherent equality of all humans, their interpretation of equality is somewhat paradoxical, since in practice they supported the unequal institutions of colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade that deprived all but White men of their natural rights.

Like Locke and his contemporaries in England, key figures of the French Enlightenment also debated the scope of natural rights. François-Marie d’Arouet, more commonly known by his pen name Voltaire, was an especially vigorous advocate of intrinsic rights and freedoms. An outspoken critic of the Catholic Church, the aristocracy, and the French monarchy, he was particularly focused on defending religious toleration, freedom of speech, and the innate utility of reason, which he did in such works as Treatise on Tolerance and Republican Ideas. In his most famous work, the 1759 satire Candide, Voltaire mocked both established religion and secular government. His contemporary Montesquieu also wrote extensively about the relationship between laws and rights. Montesquieu was principally concerned with the concept of political liberty and enforcing the separation of a state’s legislative, executive, and judicial powers as a means of keeping the government in check, which he discussed in his 1748 book The Spirit of the Laws.

The tension between state authority and the right of individuals to make decisions for themselves likewise inspired the work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose contributions to Enlightenment philosophy included his influential treatise The Social Contract. Dating to the era of Plato and Socrates in the fourth and fifth centuries BCE and to the second-century BCE Buddhist text The Mahāvastu, the social contract is an idea centered on the belief that individuals surrender their natural rights to the state, which is then charged with the task of maintaining and protecting those rights. In his assessment of natural rights, Rousseau contends that the formation of human communities makes interdependence necessary and requires reconciling individual freedoms with the sovereignty of the state. Individuals must be free to do as they choose, but the government must also be able to restrict people’s actions in order to protect the rights of all. He also discussed the theory of the general will, a concept by which a state can be legitimate only if it is guided by the will of the people as a whole, rather than the whims of an elite minority.

Whereas Locke, Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau reinforced the distinction between inalienable rights and the authority of the state, some philosophers of the era, such as Jeremy Bentham and Edmund Burke, cast doubt on the very existence of natural rights. Bentham was an English lawyer known for his adoption of utilitarianism, a political philosophy that emphasized the goal of achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people. He contended that rights came into being only as a creation of the state and did not exist outside the confines of civil society. Even if a government did not do what the general will wished or disregarded the supremacy of natural law, Bentham wrote, disputing its legitimacy could lead only to chaos and lawlessness.

Like Bentham, the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke also rejected the concept of popular sovereignty. Although he did not dispute the existence of natural law, he argued that natural rights became irrelevant with the formation of civil society, since only people of virtue and good judgment should be permitted to exercise political power. They would serve in the best interests of the people, who, according to Burke, would naturally give up their selfish desires and individual will in the interests of the state.

Although the Enlightenment produced a wide range of opinions about the origins and meaning of natural rights, it also enabled people to think more critically about their relationship with the state and the legitimacy of revolution. While some thinkers such as Burke and Bentham defended the supremacy of the state over individual rights, others such as Locke and Voltaire championed the integrity of natural rights and believed that political liberty could not be interfered with. As the argument continued during the Enlightenment period, it expanded into discussions of social contract theory that focused more specifically on the ethics and legitimacy of law and the political order.

Social Contract Theory

At the core of Enlightenment debate about the relationship between state authority and natural rights was the fundamental character of the social contract. This implicit agreement, or “contract,” compels those living in a society to abide by its rules and regulations or suffer punishments for violating them. In essence, those who enter into the social contract implicitly surrender their natural rights to the state, which is then charged with the task of maintaining and protecting those rights. However, according to many social contract theorists like Rousseau, when a state fails to maintain the general will or protect natural rights, citizens may in turn withdraw their social and moral obligations to the state.

The ultimate goal of social contract theory was to demonstrate that the rules imposed by civil society could be rationally justified, and that in its ideal form, government would effectively serve the interests of the people and uphold the general will. As a result, stability and social order would prevail for all. The roles of justice and liberty in civil society thus formed the focus of much debate among philosophers and European rulers concerned with preserving the balance between individual rights and political authority.

Enlightened despots often invited renowned philosophers to their courts to help design laws and policies that would—at least in theory—protect the essence of the social contract. Frederick of Prussia, for example, invited the French philosopher Voltaire to live at his palace in Potsdam in 1750. Although the nature of authoritarian rule may seem at odds with the preservation of natural rights and the social contract, many philosophers developed political models that appealed to enlightened despots. Locke, Rousseau, and Thomas Hobbes are often lauded in traditional historical narratives for their defense of rights and freedoms. Hobbes maintained that an absolute government, characterized by unlimited centralized political authority, provided the best means of preserving rights and freedoms in what would otherwise be an anarchic state of nature, while Rousseau and Locke extolled the virtues of more democratic political models.

In what later became the United States and in some European countries, Enlightenment theories coexisted with the institution of slavery, the appropriation of lands from Indigenous people, and access to political participation and the protections afforded by the state that were generally limited to White men of property. Social contract theorists generally justified such contradictions by asserting that because Indigenous peoples resided in a nonpolitical state, and because they were believed to lack the capacity to reason, they were not entitled to the rights and protections afforded to other peoples. Enlightenment lawyers, moreover, used social contract theory to defend slavery, on the grounds that either it was a justifiable consequence of conquest or Black people were incapable of governing themselves without the protection of White owners. Although social contract theory ultimately formed the foundations of seminal documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, the ideals of rights and freedoms it espoused coexisted with engrained racial injustices that formed the foundation of slavery and colonialism.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). The Enlightenment. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

LITERATURE

Niccolo Machiavelli The Prince

The Prince is written by Niccolò Machiavelli, an Italian Renaissance political philosopher, statesman, playwright, novelist, and poet. This booklet, composed of twenty-six chapters, is a political treatise offering advice to rulers on how to obtain and keep power. It is assumed that a version of the manuscript had been circulated from 1513 on, whereas it was first officially published in 1532, posthumously. Drawing lessons from the Roman historian Livy, its innovation lies in the treatise’s focus on the efficacy of ruling, a significant contrast from traditional Christian-morality-based instructions for rulers. Although some had even interpreted it as a satire, the adjective “Machiavellian” has come to have a pejorative connation because of the text’s apparent indifference to moral and ethical concerns.

Selections from the Prince

Nicolo Machiavelli, translated by W. K. Marriott

License: Public Domain

INTRODUCTION

Nicolo Machiavelli was born at Florence on 3rd May 1469. He was the second son of Bernardo di Nicolo Machiavelli, a lawyer of some repute, and of Bartolommea di Stefano Nelli, his wife. Both parents were members of the old Florentine nobility.

His life falls naturally into three periods, each of which singularly enough constitutes a distinct and important era in the history of Florence. His youth was concurrent with the greatness of Florence as an Italian power under the guidance of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Il Magnifico. The downfall of the Medici in Florence occurred in 1494, in which year Machiavelli entered the public service. During his official career Florence was free under the government of a Republic, which lasted until 1512, when the Medici returned to power, and Machiavelli lost his office. The Medici again ruled Florence from 1512 until 1527, when they were once more driven out. This was the period of Machiavelli’s literary activity and increasing influence; but he died, within a few weeks of the expulsion of the Medici, on 22nd June 1527, in his fifty-eighth year, without having regained office.

DEDICATION

To the Magnificent Lorenzo Di Piero De’ Medici:

Those who strive to obtain the good graces of a prince are accustomed to come before him with such things as they hold most precious, or in which they see him take most delight; whence

one sees horses, arms, cloth of gold, precious stones, and similar ornaments presented to princes, worthy of their greatness.

Desiring therefore to present myself to your Magnificence with some testimony of my devotion towards you, I have not found among my possessions anything which I hold more dear than, or value so much as, the knowledge of the actions of great men, acquired by long experience in contemporary affairs, and a continual study of antiquity; which, having reflected upon it with great and prolonged diligence, I now send, digested into a little volume, to your Magnificence.

And although I may consider this work unworthy of your countenance, nevertheless I trust much to your benignity that it may be acceptable, seeing that it is not possible for me to make a better gift than to offer you the opportunity of understanding in the shortest time all that I have learnt in so many years, and with so many troubles and dangers; which work I have not embellished with swelling or magnificent words, nor stuffed with rounded periods, nor with any extrinsic allurements or adornments whatever, with which so many are accustomed to embellish their works; for I have wished either that no honour should be given it, or else that the truth of the matter and the weightiness of the theme shall make it acceptable.

Nor do I hold with those who regard it as a presumption if a man of low and humble condition dare to discuss and settle the concerns of princes; because, just as those who draw landscapes place themselves below in the plain to contemplate the nature of the mountains and of lofty places, and in order to contemplate the plains place themselves upon high mountains, even so to understand the nature of the people it needs to be a prince, and to understand that of princes it needs to be of the people.

Take then, your Magnificence, this little gift in the spirit in which I send it; wherein, if it be diligently read and considered by you, you will learn my extreme desire that you should attain that greatness which fortune and your other attributes promise. And if your Magnificence from the summit of your greatness will sometimes turn your eyes to these lower regions, you will see how unmeritedly I suffer a great and continued malignity of fortune.

CHAPTER X

CONCERNING THE WAY IN WHICH THE STRENGTH OF ALL PRINCIPALITIES OUGHT TO BE MEASURED

It is necessary to consider another point in examining the character of these principalities: that is, whether a prince has such power that, in case of need, he can support himself with his own resources, or whether he has always need of the assistance of others. And to make this quite clear I say that I consider those who are able to support themselves by their own resources who can, either by abundance of men or money, raise a sufficient army to join battle against any one who comes to attack them; and I consider those always to have need of others who cannot show themselves against the enemy in the field, but are forced to defend themselves by sheltering behind walls. The first case has been discussed, but we will speak of it again should it recur. In the second case one can say nothing except to encourage such princes to provision and fortify their towns, and not on any account to defend the country. And whoever shall fortify his town well, and shall have managed the other concerns of his subjects in the way stated above, and to be often repeated, will never be attacked without great caution, for men are always adverse to enterprises where difficulties can be seen, and it will be seen not to be an easy thing to attack one who has his town well fortified, and is not hated by his people.

The cities of Germany are absolutely free, they own but little country around them, and they yield obedience to the emperor when it suits them, nor do they fear this or any other power they may have near them, because they are fortified in such a way that every one thinks the taking of them by assault would be tedious and difficult, seeing they have proper ditches and walls, they have sufficient artillery, and they always keep in public depots enough for one year’s eating, drinking, and firing. And beyond this, to keep the people quiet and without loss to the state, they always have the means of giving work to the community in those labours that are the life and strength of the city, and on the pursuit of which the people are supported; they also hold military exercises in repute, and moreover have many ordinances to uphold them.

Therefore, a prince who has a strong city, and had not made himself odious, will not be attacked, or if any one should attack he will only be driven off with disgrace; again, because that the affairs of this world are so changeable, it is almost impossible to keep an army a whole year in the field without being interfered with. And whoever should reply: If the people have property outside the city, and see it burnt, they will not remain patient, and the long siege and self-interest will make them forget their prince; to this I answer that a powerful and courageous prince will overcome all such difficulties by giving at one time hope to his subjects that the evil will not be for long, at another time fear of the cruelty of the enemy, then preserving himself adroitly from those subjects who seem to him to be too bold.

Further, the enemy would naturally on his arrival at once burn and ruin the country at the time when the spirits of the people are still hot and ready for the defence; and, therefore, so much the less ought the prince to hesitate; because after a time, when spirits have cooled, the damage is already done, the ills are incurred, and there is no longer any remedy; and therefore they are so much the more ready to unite with their prince, he appearing to be under obligations to them now that their houses have been burnt and their possessions ruined in his defence. For it is the nature of men to be bound by the benefits they confer as much as by those they receive. Therefore, if everything is well considered, it will not be difficult for a wise prince to keep the minds of his citizens steadfast from first to last, when he does not fail to support and defend them.

CHAPTER XI

CONCERNING ECCLESIASTICAL PRINCIPALITIES

It only remains now to speak of ecclesiastical principalities, touching which all difficulties are prior to getting possession, because they are acquired either by capacity or good fortune, and they can be held without either; for they are sustained by the ancient ordinances of religion, which are so all-powerful, and of such a character that the principalities may be held no matter how their princes behave and live. These princes alone have states and do not defend them; and they have subjects and do not rule them; and the states, although unguarded, are not taken from them, and the subjects, although not ruled, do not care, and they have neither the desire nor the ability to alienate themselves. Such principalities only are secure and happy. But being upheld by powers, to which the human mind cannot reach, I shall speak no more of them, because, being exalted and maintained by God, it would be the act of a presumptuous and rash man to discuss them.

Nevertheless, if any one should ask of me how comes it that the Church has attained such greatness in temporal power, seeing that from Alexander backwards the Italian potentates (not only those who have been called potentates, but every baron and lord, though the smallest) have valued the temporal power very slightly—yet now a king of France trembles before it, and it has been able to drive him from Italy, and to ruin the Venetians— although this may be very manifest, it does not appear to me superfluous to recall it in some measure to memory.

Before Charles, King of France, passed into Italy37, this country was under the dominion of the Pope, the Venetians, the King of Naples, the Duke of Milan, and the Florentines. These potentates had two principal anxieties: the one, that no foreigner should enter Italy under arms; the other, that none of themselves should seize more territory. Those about whom there was the most anxiety were the Pope and the Venetians. To restrain the Venetians the union of all the others was necessary, as it was for the defence of Ferrara; and to keep down the Pope they made use of the barons of Rome, who, being divided into two factions, Orsini and Colonnesi, had always a pretext for disorder, and, standing with arms in their hands under the eyes of the Pontiff, kept the pontificate weak and powerless. And although there might arise sometimes a courageous pope, such as Sixtus, yet neither fortune nor wisdom could rid him of these annoyances. And the short life of a pope is also a cause of weakness; for in the ten years, which is the average life of a pope, he can with difficulty lower one of the factions; and if, so to speak, one people should almost destroy the Colonnesi, another would arise hostile to the Orsini, who would support their opponents, and yet would not have time to ruin the Orsini. This was the reason why the temporal powers of the pope were little esteemed in Italy.

Alexander the Sixth arose afterwards, who of all the pontiffs that have ever been showed how a pope with both money and arms was able to prevail; and through the instrumentality of the Duke Valentino, and by reason of the entry of the French, he brought about all those things which I have discussed above in the actions of the duke. And although his intention was not to aggrandize the Church, but the duke, nevertheless, what he did contributed to the greatness of the Church, which, after his death and the ruin of the duke, became the heir to all his labours.

Pope Julius came afterwards and found the Church strong, possessing all the Romagna, the barons of Rome reduced to impotence, and, through the chastisements of Alexander, the factions wiped out; he also found the way open to accumulate money in a manner such as had never been practised before Alexander’s time. Such things Julius not only followed, but improved upon, and he intended to gain Bologna, to ruin the Venetians, and to drive the French out of Italy. All of these enterprises prospered with him, and so much the more to his credit, inasmuch as he did everything to strengthen the Church and not any private person. He kept also the Orsini and Colonnesi factions within the bounds in which he found them; and although there was among them some mind to make disturbance, nevertheless he held two things firm: the one, the greatness of the Church, with which he terrified them; and the other, not allowing them to have their own cardinals, who caused the disorders among them. For whenever these factions have their cardinals they do not remain quiet for long, because cardinals foster the factions in Rome and out of it, and the barons are compelled to support them, and thus from the ambitions of prelates arise disorders and tumults among the barons. For these reasons his Holiness Pope Leo38 found the pontificate most powerful, and it is to be hoped that, if others made it great in arms, he will make it still greater and more venerated by his goodness and infinite other virtues.

CHAPTER XIV

THAT WHICH CONCERNS A PRINCE ON THE SUBJECT OF THE ART OF WAR

A prince ought to have no other aim or thought, nor select anything else for his study, than war and its rules and discipline; for this is the sole art that belongs to him who rules, and it is of such force that it not only upholds those who are born princes, but it often enables men to rise from a private station to that rank. And, on the contrary, it is seen that when princes have thought more of ease than of arms they have lost their states. And the first cause of your losing it is to neglect this art; and what enables you to acquire a state is to be master of the art. Francesco Sforza, through being martial, from a private person became Duke of Milan; and the sons, through avoiding the hardships and troubles of arms, from dukes became private persons. For among other evils which being unarmed brings you, it causes you to be despised, and this is one of those ignominies against which a prince ought to guard himself, as is shown later on. Because there is nothing proportionate between the armed and the unarmed; and it is not reasonable that he who is armed should yield obedience willingly to him who is unarmed, or that the unarmed man should be secure among armed servants. Because, there being in the one disdain and in the other suspicion, it is not possible for them to work well together. And therefore a prince who does not understand the art of war, over and above the other misfortunes already mentioned, cannot be respected by his soldiers, nor can he rely on them. He ought never, therefore, to have out of his thoughts this subject of war, and in peace he should addict himself more to its exercise than in war; this he can do in two ways, the one by action, the other by study.

As regards action, he ought above all things to keep his men well organized and drilled, to follow incessantly the chase, by which he accustoms his body to hardships, and learns something of the nature of localities, and gets to find out how the mountains rise, how the valleys open out, how the plains lie, and to understand the nature of rivers and marshes, and in all this to take the greatest care. Which knowledge is useful in two ways. Firstly, he learns to know his country, and is better able to undertake its defence; afterwards, by means of the knowledge and observation of that locality, he understands with ease any other which it may be necessary for him to study hereafter; because the hills, valleys, and plains, and rivers and marshes that are, for instance, in Tuscany, have a certain resemblance to those of other countries, so that with a knowledge of the aspect of one country one can easily arrive at a knowledge of others. And the prince that lacks this skill lacks the essential which it is desirable that a captain should possess, for it teaches him to surprise his enemy, to select quarters, to lead armies, to array the battle, to besiege towns to advantage.

Philopoemen,39 Prince of the Achaeans, among other praises which writers have bestowed on him, is commended because in time of peace he never had anything in his mind but the rules of war; and when he was in the country with friends, he often stopped and reasoned with them: “If the enemy should be upon that hill, and we should find ourselves here with our army, with whom would be the advantage? How should one best advance to meet him, keeping the ranks? If we should wish to retreat, how ought we to pursue?” And he would set forth to them, as he went, all the chances that could befall an army; he would listen to their opinion and state his, confirming it with reasons, so that by these continual discussions there could never arise, in time of war, any unexpected circumstances that he could not deal with.

But to exercise the intellect the prince should read histories, and study there the actions of illustrious men, to see how they have borne themselves in war, to examine the causes of their victories and defeat, so as to avoid the latter and imitate the former; and above all do as an illustrious man did, who took as an exemplar one who had been praised and famous before him, and whose achievements and deeds he always kept in his mind, as it is said Alexander the Great imitated Achilles, Caesar Alexander, Scipio Cyrus. And whoever reads the life of Cyrus, written by Xenophon, will recognize afterwards in the life of Scipio how that imitation was his glory, and how in chastity, affability, humanity, and liberality Scipio conformed to those things which have been written of Cyrus by Xenophon. A wise prince ought to observe some such rules, and never in peaceful times stand idle, but increase his resources with industry in such a way that they may be available to him in adversity, so that if fortune chances it may find him prepared to resist her blows.

CHAPTER XVII

CONCERNING CRUELTY AND CLEMENCY, AND WHETHER IT IS BETTER TO BE LOVED THAN FEARED

Coming now to the other qualities mentioned above, I say that every prince ought to desire to be considered clement and not cruel. Nevertheless he ought to take care not to misuse this clemency. Cesare Borgia was considered cruel; notwithstanding, his cruelty reconciled the Romagna, unified it, and restored it to peace and loyalty. And if this be rightly considered, he will be seen to have been much more merciful than the Florentine people, who, to avoid a reputation for cruelty, permitted Pistoia to be destroyed.40 Therefore a prince, so long as he keeps his subjects united and loyal, ought not to mind the reproach of cruelty; because with a few examples he will be more merciful than those who, through too much mercy, allow disorders to arise, from which follow murders or robberies; for these are wont to injure the whole people, whilst those executions which originate with a prince offend the individual only.

And of all princes, it is impossible for the new prince to avoid the imputation of cruelty, owing to new states being full of dangers. Hence Virgil, through the mouth of Dido, excuses the inhumanity of her reign owing to its being new, saying:

“Res dura, et regni novitas me talia cogunt

Moliri, et late fines custode tueri.”41

Nevertheless he ought to be slow to believe and to act, nor should he himself show fear, but proceed in a temperate manner with prudence and humanity, so that too much confidence may not make him incautious and too much distrust render him intolerable.

Upon this a question arises: whether it be better to be loved than feared or feared than loved? It may be answered that one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with. Because this is to be asserted in general of men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous, and as long as you succeed they are yours entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and children, as is said above, when the need is far distant; but when it approaches they turn against you. And that prince who, relying entirely on their promises, has neglected other precautions, is ruined; because friendships that are obtained by payments, and not by greatness or nobility of mind, may indeed be earned, but they are not secured, and in time of need cannot be relied upon; and men have less scruple in offending one who is beloved than one who is feared, for love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of punishment which never fails.

Nevertheless a prince ought to inspire fear in such a way that, if he does not win love, he avoids hatred; because he can endure very well being feared whilst he is not hated, which will always be as long as he abstains from the property of his citizens and subjects and from their women. But when it is necessary for him to proceed against the life of someone, he must do it on proper justification and for manifest cause, but above all things he must keep his hands off the property of others, because men more quickly forget the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony. Besides, pretexts for taking away the property are never wanting; for he who has once begun to live by robbery will always find pretexts for seizing what belongs to others; but reasons for taking life, on the contrary, are more difficult to find and sooner lapse. But when a prince is with his army, and has under control a multitude of soldiers, then it is quite necessary for him to disregard the reputation of cruelty, for without it he would never hold his army united or disposed to its duties.

Among the wonderful deeds of Hannibal this one is enumerated: that having led an enormous army, composed of many various races of men, to fight in foreign lands, no dissensions arose either among them or against the prince, whether in his bad or in his good fortune. This arose from nothing else than his inhuman cruelty, which, with his boundless valour, made him revered and terrible in the sight of his soldiers, but without that cruelty, his other virtues were not sufficient to produce this effect. And short-sighted writers admire his deeds from one point of view and from another condemn the principal cause of them. That it is true his other virtues would not have been sufficient for him may be proved by the case of Scipio, that most excellent man, not only of his own times but within the memory of man, against whom, nevertheless, his army rebelled in Spain; this arose from nothing but his too great forbearance, which gave his soldiers more license than is consistent with military discipline. For this he was upbraided in the Senate by Fabius Maximus, and called the corrupter of the Roman soldiery. The Locrians were laid waste by a legate of Scipio, yet they were not avenged by him, nor was the insolence of the legate punished, owing entirely to his easy nature. Insomuch that someone in the Senate, wishing to excuse him, said there were many men who knew much better how not to err than to correct the errors of others. This disposition, if he had been continued in the command, would have destroyed in time the fame and glory of Scipio; but, he being under the control of the Senate, this injurious characteristic not only concealed itself, but contributed to his glory.

Returning to the question of being feared or loved, I come to the conclusion that, men loving according to their own will and fearing according to that of the prince, a wise prince should establish himself on that which is in his own control and not in that of others; he must endeavour only to avoid hatred, as is noted.

Copyright: World Literature Copyright © by Anita Turlington; Rhonda Kelley; Matthew Horton; Laura Ng; Kyounghye Kwon; Laura Getty; Karen Dodson; and Douglas Thomson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Thomas More Utopia

Thomas More invented the word utopia, a word that literally translates as not place (from the Greek ou-topos) or nowhere, although it sounds like good place (eu-topos in Greek). As the double meaning indicates, More’s invented society may sound great, but it does not actually exist. In More’s work, the country of Utopia is in the New World, and details about it are reported by Hythloday, a sailor whose name translates as “speaker of nonsense.” What follows is actually a criticism of the Old World, in that the Utopians do well in all of the things that More thinks that his society does poorly; for example, as More praises the Utopians for consciously despising gold, he implicitly condemns his own society, which he says will scarcely believe that any society would not desire gold. Other authors followed his lead (such as Jonathan Swift, who plays with the idea of utopia in Gulliver’s Travels), and eventually utopian literature led to another genre: dystopian literature, such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, movies such as Blade Runner, and a list of young adult novels, including The Hunger Games.

Selections from Utopia

Henry VIII., the unconquered King of England, a prince adorned with all the virtues that become a great monarch, having some differences of no small consequence with Charles the most serene Prince of Castile, sent me into Flanders, as his ambassador, for treating and composing matters between them. I was colleague and companion to that incomparable man Cuthbert Tonstal, whom the King, with such universal applause, lately made Master of the Rolls; but of whom I will say nothing; not because I fear that the testimony of a friend will be suspected, but rather because his learning and virtues are too great for me to do them justice, and so well known, that they need not my commendations, unless I would, according to the proverb, “Show the sun with a lantern.” Those that were appointed by the Prince to treat with us, met us at Bruges, according to agreement; they were all worthy men. The Margrave of Bruges was their head, and the chief man among them; but he that was esteemed the wisest, and that spoke for the rest, was George Temse, the Provost of Casselsee: both art and nature had concurred to make him eloquent: he was very learned in the law; and, as he had a great capacity, so, by a long practice in affairs, he was very dexterous at unravelling them. After we had several times met, without coming to an agreement, they went to Brussels for some days, to know the Prince’s pleasure; and, since our business would admit it, I went to Antwerp. While I was there, among many that visited me, there was one that was more acceptable to me than any other, Peter Giles, born at Antwerp, who is a man of great honour, and of a good rank in his town, though less than he deserves; for I do not know if there be anywhere to be found a more learned and a better bred young man; for as he is both a very worthy and a very knowing person, so he is so civil to all men, so particularly kind to his friends, and so full of candour and affection, that there is not, perhaps, above one or two anywhere to be found, that is in all respects so perfect a friend: he is extraordinarily modest, there is no artifice in him, and yet no man has more of a prudent simplicity. His conversation was so pleasant and so innocently cheerful, that his company in a great measure lessened any longings to go back to my country, and to my wife and children, which an absence of four months had quickened very much. One day, as I was returning home from mass at St. Mary’s, which is the chief church, and the most frequented of any in Antwerp, I saw him, by accident, talking with a stranger, who seemed past the flower of his age; his face was tanned, he had a long beard, and his cloak was hanging carelessly about him, so that, by his looks and habit, I concluded he was a seaman. As soon as Peter saw me, he came and saluted me, and as I was returning his civility, he took me aside, and pointing to him with whom he had been discoursing, he said, “Do you see that man? I was just thinking to bring him to you.” I answered, “He should have been very welcome on your account.” “And on his own too,” replied he, “if you knew the man, for there is none alive that can give so copious an account of unknown nations and countries as he can do, which I know you very much desire.” “Then,” said I, “I did not guess amiss, for at first sight I took him for a seaman.” “But you are much mistaken,” said he, “for he has not sailed as a seaman, but as a traveller, or rather a philosopher. This Raphael, who from his family carries the name of Hythloday, is not ignorant of the Latin tongue, but is eminently learned in the Greek, having applied himself more particularly to that than to the former, because he had given himself much to philosophy, in which he knew that the Romans have left us nothing that is valuable, except what is to be found in Seneca and Cicero. He is a Portuguese by birth, and was so desirous of seeing the world, that he divided his estate among his brothers, ran the same hazard as Americus Vesputius, and bore a share in three of his four voyages that are now published; only he did not return with him in his last, but obtained leave of him, almost by force, that he might be one of those twenty-four who were left at the farthest place at which they touched in their last voyage to New Castile. The leaving him thus did not a little gratify one that was more fond of travelling than of returning home to be buried in his own country; for he used often to say, that the way to heaven was the same from all places, and he that had no grave had the heavens still over him. Yet this disposition of mind had cost him dear, if God had not been very gracious to him; for after he, with five Castalians, had travelled over many countries, at last, by strange good fortune, he got to Ceylon, and from thence to Calicut, where he, very happily, found some Portuguese ships; and, beyond all men’s expectations, returned to his native country.” When Peter had said this to me, I thanked him for his kindness in intending to give me the acquaintance of a man whose conversation he knew would be so acceptable; and upon that Raphael and I embraced each other. After those civilities were past which are usual with strangers upon their first meeting, we all went to my house, and entering into the garden, sat down on a green bank and entertained one another in discourse. He told us that when Vesputius had sailed away, he, and his companions that stayed behind in New Castile, by degrees insinuated themselves into the affections of the people of the country, meeting often with them and treating them gently; and at last they not only lived among them without danger, but conversed familiarly with them, and got so far into the heart of a prince, whose name and country I have forgot, that he both furnished them plentifully with all things necessary, and also with the conveniences of travelling, both boats when they went by water, and waggons when they trained over land: he sent with them a very faithful guide, who was to introduce and recommend them to such other princes as they had a mind to see: and after many days’ journey, they came to towns, and cities, and to commonwealths, that were both happily governed and well peopled. Under the equator, and as far on both sides of it as the sun moves, there lay vast deserts that were parched with the perpetual heat of the sun; the soil was withered, all things looked dismally, and all places were either quite uninhabited, or abounded with wild beasts and serpents, and some few men, that were neither less wild nor less cruel than the beasts themselves. But, as they went farther, a new scene opened, all things grew milder, the air less burning, the soil more verdant, and even the beasts were less wild: and, at last, there were nations, towns, and cities, that had not only mutual commerce among themselves and with their neighbours, but traded, both by sea and land, to very remote countries. There they found the conveniencies of seeing many countries on all hands, for no ship went any voyage into which he and his companions were not very welcome. The first vessels that they saw were flat-bottomed, their sails were made of reeds and wicker, woven close together, only some were of leather; but, afterwards, they found ships made with round keels and canvas sails, and in all respects like our ships, and the seamen understood both astronomy and navigation. He got wonderfully into their favour by showing them the use of the needle, of which till then they were utterly ignorant. They sailed before with great caution, and only in summer time; but now they count all seasons alike, trusting wholly to the loadstone, in which they are, perhaps, more secure than safe; so that there is reason to fear that this discovery, which was thought would prove so much to their advantage, may, by their imprudence, become an occasion of much mischief to them. But it were too long to dwell on all that he told us he had observed in every place, it would be too great a digression from our present purpose: whatever is necessary to be told concerning those wise and prudent institutions which he observed among civilised nations, may perhaps be related by us on a more proper occasion. We asked him many questions concerning all these things, to which he answered very willingly; we made no inquiries after monsters, than which nothing is more common; for everywhere one may hear of ravenous dogs and wolves, and cruel men-eaters, but it is not so easy to find states that are well and wisely governed.