48 EASTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

Colonialism in East Asia

British attempts to gain control over regions of Asia beyond India and Hong Kong were often frustrated by Russia, which also sought to expand its influence there. The ongoing struggle between the two was called The Great Game. From the 1850s through the 1870s, Russia gained control of kingdoms occupied by Turkic-speaking peoples in central Asia and incorporated them into its empire as a region called Turkestan (Figure 9.22). Russia argued that its actions were necessary to “civilize” the region’s inhabitants and protect important trade routes. Britain feared Russia would try to absorb India as well. To protect its prized possession, Britain sought to use the Emirate of Afghanistan as a buffer zone. When its diplomats were refused admission to Afghanistan in 1878, the British army invaded. Britain emerged victorious, gaining the right to act as a go-between for Afghanistan and Russia. When Russia gained control of much of what is now Turkmenistan in 1881, the two European nations jointly established the boundary line between an independent Afghanistan and Russian territory, ending a serious conflict between the two powers.

Russia also desired to expand control over the far eastern end of its empire, on the Pacific coast. Here, however, it found itself in conflict with a new imperial power—Japan. Lacking many of the raw materials necessary for industrialization, Japan, like other industrialized nations, began to seek them abroad. It first took control of the Ryukyu Islands and also claimed the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin Island (Figure 9.23). Russia, however, also laid claim to these territories, and for a while the two nations shared Sakhalin Island. In 1875, Japan relinquished its claims to the island in exchange for complete control over the Kurile Islands.

Japan’s most desired prize was Korea, then a largely isolated tributary state of China. Japan traded with Korea but in a limited way. In 1873, however, Korea’s King Gojong began to consider opening the nation to the outside world. Anxious to gain an advantage, in 1876 Japan sent a gunboat to force Korea to sign the Japan-Korea Treaty of Amity (Ganghwa Treaty) before it could make commercial treaties with other nations. Among other provisions, the treaty allowed the Japanese to establish trading ports in addition to the one to which they already had access. It also let Japanese merchants live and work in Korea while subject only to Japanese law. In addition, Korea was declared to no longer be a tributary state of China (Figure 9.24).

Although China had the larger military force by far, Japan’s navy was much more modern and defeated the Chinese handily. Humiliated, China signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, which recognized Korea’s independence and conceded to Japan territory on the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria as well as Taiwan and the Penghu Islands. Japan had now acquired an empire. Japan quickly realized, however, that it would have to defend its gains from its old rival Russia. In 1896, Koreans, angered by the assassination of their pro-Chinese queen by Japanese agents, overthrew the pro-Japanese government then in power. As Japanese influence waned, Russian influence grew, and Russia soon acquired mineral and timber rights in the northern Korean peninsula.

Russia also began to encroach upon Japanese territory in Manchuria. Russia’s one Pacific port, Vladivostok, was often frozen over. Seeking a harbor that was ice-free year-round, Russia leased land from China on the Liaodong Peninsula in 1897 and built a new port, Port Arthur. A wary Japan offered Russia free rein on the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for Japan’s retaining control over Korea. When Russia refused to compromise, Japan attacked the Russian fleet at Port Arthur in the winter of 1904, beginning the Russo-Japanese War. Once again, Japan emerged victorious over a much larger nation. The Treaty of Portsmouth, signed in September 1905, acknowledged Japan’s right to Korea and awarded Japan control of southern Manchuria. Japan formally annexed Korea in 1910.

As Japan, Russia, and Britain competed for control of Asia, France largely refrained. Its principal interest on the continent of Asia was Indochina (now Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). In 1858, the emperor of Vietnam ordered French missionaries in the country to leave. In response, Napoleon III sent gunboats to protect the missionaries and their Christian converts and forced the emperor to grant France control over three southern provinces. When the Vietnamese ruler proved unwilling to abide by the terms, troops returned in 1862, forcing him to concede yet more territory. By 1887, France had established protectorates over the remaining provinces of Vietnam and over Cambodia, a vassal state of the emperor of Siam (now Thailand). Laos, also Siamese territory, became part of French Indochina after a brief military conflict between Siam and France in 1893.

China could do little as Asia was devoured. By the second half of the nineteenth century, China was a shadow of its former self. Defeat in the Opium Wars of 1839 and 1856 had weakened it, and the peace treaties concluding the Second Opium War had forced it to open additional ports and allow British, French, Russian, and U.S. citizens to travel freely and enjoy the right of extraterritoriality, meaning that while in China they were subject only to the laws of their own countries. China was also forced to allow the practice of Christianity.

Alarmed by their nation’s inability to defend itself against foreign threats, many Chinese in the 1860s began to call for reform. Among them was Feng Guifen, a scholar and government official who advocated the adoption of western military technology and the study of western science. Military leaders such as Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang also supported these reforms. The reformist Self-Strengthening Movement was championed by Prince Gong, who had negotiated with the British and French invaders in 1860. Arsenals to build and house modern weapons and shipyards to construct modern warships were established (Figure 9.25). Efforts were made to build railroad and telegraph lines and to open iron and coal mines. Although they still clung to traditional Confucian values, the leaders of the movement also advocated educational reform with a new emphasis on mathematics, science, and foreign languages (so foreign books could be translated) instead of the Confucian classics. They regarded the Self-Strengthening Movement as a way of saving the Qing dynasty, not undermining it.

Following China’s defeat in 1895, European nations and the United States pushed for even more advantages. France gained control over the provinces of Guizhou, Guangxi, and Yunnan. Britain extended its influence along the Yangtze River Valley. Germany was given control of the Yellow River Valley to the north as well as the Shandong Peninsula and Jiaozhou Bay. Soon nearly all the industrialized nations had been granted concessions, enclaves within port cities such as Tianjin and Shanghai, where they exercised the rights of extraterritoriality.

In 1900, several of these nations signed a treaty with the Chinese government at the urging of John Hay, the U.S. secretary of state. The treaty established an Open Door policy in which China agreed to trade with all countries on the same terms. In this way, none of the industrialized powers could gain an advantage over the others. In exchange, they promised not to annex any of China’s territory.

Democratic Yearnings

The dismantling of empires at the end of the war was clearly a boon for democracy, but it was not always easy for fledgling countries to adopt new political systems. The tense situation in Ireland of the 1920s was just one example.

Japan also took steps toward becoming more democratic for a brief period after World War I. In 1912, a new emperor, Taisho, had ushered in a period of liberalism with democratic and progressive politics. For example, labor strikes, such as the rice riots in 1918 in which tens of thousands of people protested the government’s failure to pay market prices for rice, became increasingly common as workers fought for better wages and working conditions. Women became active in labor unions and politics for the first time, and the number of unions more than tripled in the 1910s. During this period, Japan was viewed as a triumph of constitutional government.

However, the progressive period did not last long. In 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake, measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale, destroyed two major cities, Yokohama and Tokyo. Nearly 150,000 people died in the earthquake and the resulting fires and tsunamis (Figure 12.18). Rumors quickly spread that Koreans in the area were taking advantage of the chaos, were plotting political insurrection, and had already poisoned wells to contaminate the drinking water. Several thousand Koreans were targeted and killed in response. The devastation also provided an opportunity for the conservative and pro-military forces in the Japanese government to exercise increased control over society. Martial law was declared, and the repression of radicals was stepped up. Political activists who questioned government policies disappeared.

Operating with a heightened sense of duty and honor, Japan’s military establishment and certain factions of its army became increasingly contemptuous of civilian leaders. By the late 1920s, they saw these politicians as incapable of solving domestic issues or addressing challenges from China and the Soviet Union. Some disaffected Japanese field commanders in China and the Japanese colony of Korea began to engage in direct actions, forming criminal conspiracies and cover-ups to secure the future of Japan as they saw it, even as they served the emperor.

Nationalistic secret societies such as the Cherry Blossom Association and the Blood-Pledge Corps blossomed within the Japanese armed forces, particularly in the prestigious Kwantung Army stationed in Korea. The Japanese chafed at perceived unequal treatment in world affairs, such as at the Washington Naval Conference. Anxiety rose about the growth of Chinese nationalism under Chiang Kai-shek and the nationalist Guomindang government, and what it might mean for Japanese interests in China.

Manchuria, which bordered Korea, was a semiautonomous province of China. In 1931, to precipitate a political crisis that would enable Japan to intervene, hyper-patriots in the Japanese army conspired to blow up a portion of the South Manchurian Railway near the Manchurian city of Mukden (Shenyang) and blamed the incident on Chinese nationalists. The local Japanese commander took the opportunity to occupy Mukden, and field commanders in Korea dispatched reinforcements without any orders from Tokyo to do so. Japanese public opinion supported the army’s action.

As the Japanese army fanned out in Manchuria, the Kwantung Army approached the former Chinese Emperor, Pu Yi, who had been living in the Japanese concession (an area of the city granted to Japan) in Tianjin since 1925 (Figure 12.19). The Japanese convinced Pu Yi they had acted in the interests of the Manchurian people to preserve law and order in his homeland. They then smuggled him back to Manchuria, and by March 1932, he had been persuaded to accept the position of “chief executive” of the newly born state of Manchukuo, otherwise known as Manchuria. As the Chinese government called for the League of Nations to intervene and pledged to accept its rulings, a British diplomat in Japan warned of “an atmosphere of gun-grease” in Japan.

Chinese public opinion was aroused, and in January 1932, clashes erupted between Japanese marines and Chinese troops in the outskirts of Shanghai. In Manchuria, the Lytton Commission found that the Guomindang government of China “was no longer exercising any political or administrative ‘authority in any part of Manchuria.’” Japan formally recognized the establishment of Manchukuo, its client state (a subordinate and dependent area), as a theoretically free, completely sovereign, and independent nation (Figure 12.20). The Lytton Report, published in October 1932, found fault on both sides but did not recommend full autonomy for Manchukuo. Japan responded by withdrawing from the League in March 1933. Japan ran the government in Manchukuo as a puppet state, controlling the native Chinese officials. Pu Yi continued as “head” of the government there until the end of the war, after which China took back control.

The Japanese secret societies within the military were animated by an exaggerated sense of Japan’s destiny. They began a campaign of violence against the Japanese civilian government. Elements of the Imperial Navy launched a coup in March 1932 by executing Japan’s former finance minister, Junnosuke Inoue, and Baron Dan, the head of Mitsui Corporation, as traitors to the Japanese people. On May 15, Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi was shot to death by eleven young naval officers. Between 1930 and 1935, the Japanese witnessed twenty terrorist incidents, the assassination of four political leaders, the attempted murders of five others, and four coup attempts.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the dominant political party in Japan was a fusion of Meiji oligarchs, government bureaucrats, and recruits from other political parties. The Seiyukai, as it was named, consistently supported a march toward authoritarian government. Beginning in 1932, “national unity” governments dominated by high-ranking military officers increasingly assumed power and repressed threats and enemies. Authoritarian government took hold from the top down in the mid-1930s, as the military intimidated and overpowered civilian governance and created a military dictatorship.

The situation in China was quite fluid through the 1920s and 1930s. Revolutionary activity grew but splintered, and the opposing views of Communists and Nationalists led to civil war. The Guomindang was led by Sun Yat-sen from 1912 until his death in 1925. Sun Yat-sen developed a more inclusive party and made an alliance with those who followed the communist path. After his death, Chiang Kai-shek arose as the leader of the Nationalists. Chiang focused on more traditional positions, and in the late 1920s, he chose to formally oust the communist members of the Guomindang.

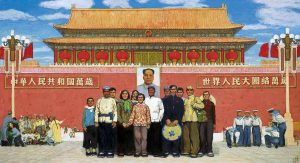

One of the people who had joined the communist ranks was a young member from Hunan Province, Mao Zedong (Figure 12.21). Mao had had intermittent schooling but was drawn to the revolutionary fervor of the Russian Revolution of 1917. He had supported both the communist cause and the Guomindang, but after Chiang ousted the communists, Mao took up arms against him.

The Nationalists themselves had encouraged assistance from the Soviet Union in the early 1920s, and the Soviet Union had responded with aid and training. Once Chiang became head of the Nationalists, however, he decided to break with the Communists and planned an extermination of the Communist forces. This forced many into hiding, but in 1935, Mao was able to lead them on the Long March to a safe retreat in northern China. Many flocked to Mao and his oratory about a new government in China that reflected the will of the people. In 1937, however, the Japanese Empire invaded mainland China. Chiang offered Mao a truce, setting aside the civil war in favor of fighting against the invading forces. Still, the internal battles between these two sides weakened the war effort against the Japanese.

The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution

Mao Zedong wanted China to chart the direction that communism took in Asia, just as the Soviet Union determined its direction in Europe. To do so, however, China needed to be much more powerful than it was in 1949, when the CCP declared the foundation of the People’s Republic and the Nationalists fled. In imitation of the Soviet model, Mao instituted a Five-Year Plan in China in 1953 and embarked on nearly seven hundred industrial projects, more than one hundred with the assistance of the Soviet Union. He also began the collectivization of agriculture by forcing peasants to labor together on state-owned farms instead of tending to farms worked by individual families. The plan was largely successful in terms of industrial development, and China’s steelmaking, coal mining, and machine- and cement-producing capacity all increased.

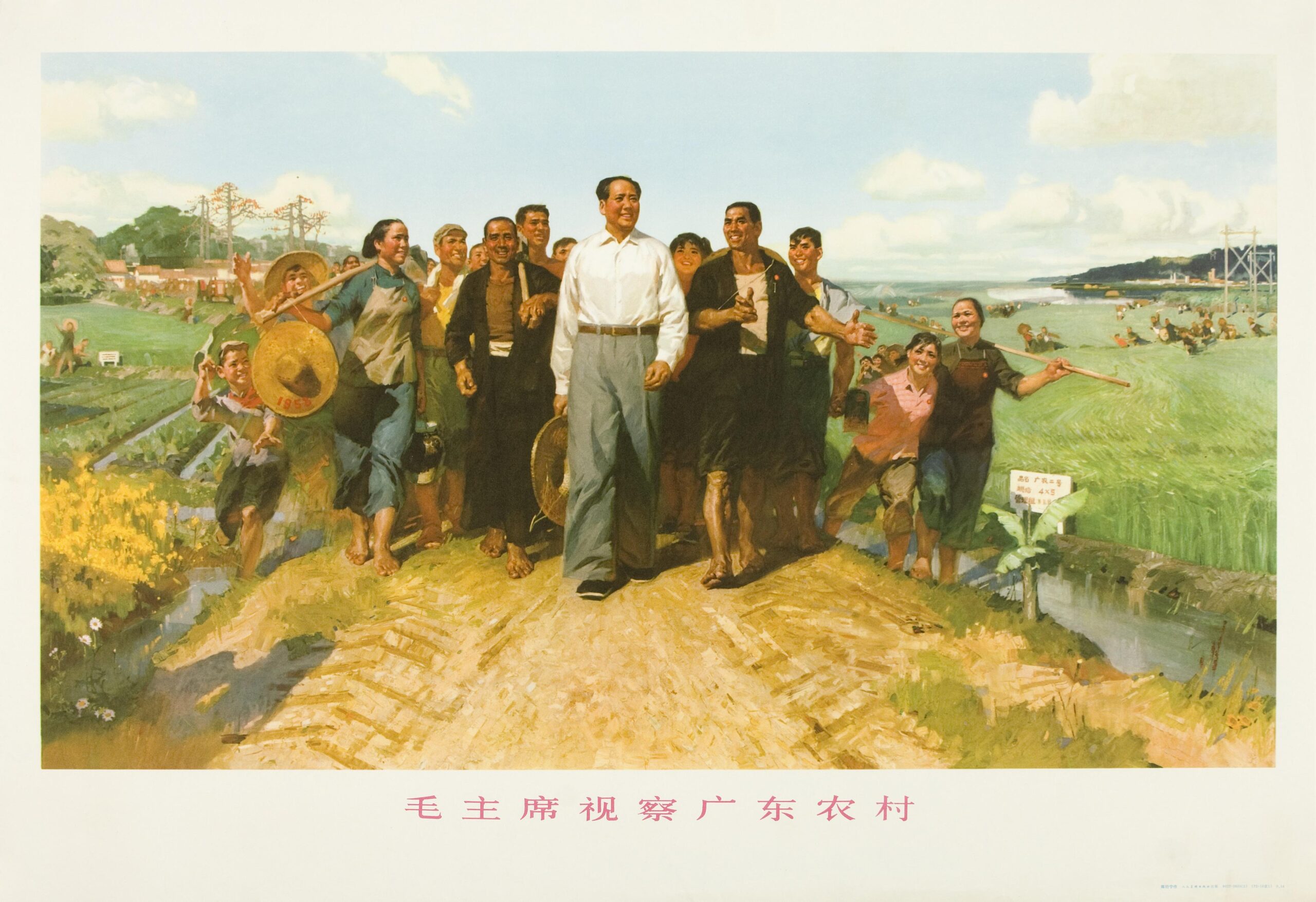

Although the first Five-Year Plan was successful, the second Five-Year Plan proved a disaster. This plan, also known as the Great Leap Forward, began in 1958. Mao, inspired by the Soviet Union’s plans to overtake the United States in industrial capacity, proclaimed that China would surpass the United Kingdom. To that end, agricultural production was to increase at the same time as industrial production, and the proceeds of agriculture would fund industry. Collectivization efforts were intensified, and by the end of 1958 more than twenty-five thousand communes had been created, each consisting of several thousand families on average.

Communes were large units of production. Members worked together to grow crops in warm months and build construction projects during the winter. Food was prepared in communal kitchens, and everyone ate together in communal dining halls. Communes also operated schools and hospitals for their members. All tools, livestock, food, and other valuable items belonged to the commune as a whole instead of to individuals or families, and the commune’s leaders determined what work each member would do. Grain produced by communes in the countryside fed city dwellers and industrial workers. Encouraged to grow ever more, communes began to exaggerate their grain production levels to win political favor. Even as they strove to grow more food, laborers were also ordered to engage in extra projects like dam construction.

Farm laborers were also ordered to produce steel in backyard furnaces hastily built in the countryside (Figure 14.11). Some were assigned to steel production exclusively, but others who worked in the fields by day were often forced to tend the furnaces at night. To meet quotas, they stripped the countryside of wood and burned their own furniture to fuel the furnaces. In the end, the steel produced was of such low quality that it was worthless.

The stupendous failure of the Great Leap Forward stunned Mao. He turned to other members of the CCP, Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, and Liu Shaoqi, to rectify the situation and allowed them to largely assume day-to-day control of China. Deng especially began to reverse some of Mao’s more damaging policies by, for example, allowing peasants to sell grain surpluses. Given positive incentives to produce more food, the peasants did so, alleviating food shortages. Mao was sensitive to failure, however, and resented the successes of Zhou, Deng, and Liu. When Marshall Peng Dehuai, the Minister of Defense and a longtime associate of Mao, criticized his handling of the Great Leap Forward, Mao dismissed him from his position and replaced him with Lin Biao.

In 1966, Mao abruptly warned that “revisionists” were seeking to alter the direction of the CCP. He called on the younger generation of Chinese people—high school and university students and young factory workers—to engage in “class struggle” and save the revolution. In July 1966 he launched the event known as the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Students organized themselves into groups of “Red Guards,” guided by quotations of Mao that Lin Biao had gathered and published in a “Little Red Book.”

In August 1966, millions of Red Guards rallied in Beijing as Mao and Lin Biao encouraged them to purge the country of “bourgeois” elements by attacking the “Four Olds”: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. Red Guards then attacked and killed their teachers and school administrators. At one school, students beat the gardener to death because he tended the lawn, a bourgeois concern. Provided with food and lodging at government expense, Red Guards rampaged through the country, destroying books, works of art, temples, monasteries, tombs, and historical sites. They beat people and forced them to confess to having bourgeois thoughts. No one knows how many were killed during the Cultural Revolution; it may have been as many as two million.

Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, who displayed insufficient revolutionary fervor, were removed from positions of power. In 1968, the Red Guards were themselves dismissed as Mao sought to curb their power. They were sent to the countryside along with other urban youth to learn from the peasants. In 1969, Lin Biao was named Mao’s successor. Two years later, Lin died in a plane crash while attempting to flee to the Soviet Union. He may have feared that Mao suspected him of plotting against him and planned to punish him.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

LITERATURE

Lu Xun- Diary of a Madman

“Diary of a Madman” is a famous short story by Lu Xun, who is regarded as a great writer of modern Chinese literature. Lu Xun (surname: Lu, and the pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a short story writer, translator, essayist, and literary scholar. Although Lu was educated in the Confucian tradition when he was young, he later received a modern western education; he studied modern medicine in Japan and was exposed to western literature (including English, German, and Russian literatures). In 1918, “Diary of a Madman” was published in New Youth, a magazine of the New Culture Movement that promoted democracy, egalitarianism, vernacular literature, individual freedom, and women’s rights. Inspired by the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol’s story of the same title, Lu wrote this story, which is the first western-style story in vernacular Chinese. The cannibalistic society that the madman narrator sees is generally interpreted as a satirical allegory of traditional Chinese society based on Confucianism. Although Lu and his works were associated with leftist ideas (and Mao Zedong favored Lu’s works), Lu never joined the Communist Party of China. The English translations of this short story include a version by William A. Lyell, a former professor of Chinese at Stanford University.

Consider while reading:

- What difference is there between the language and style of the preface and those of the “diary”?

- According to the “madman,” what is the evidence of cannibalism in China?

- How reliable is the story of the “madman”?

- What could be the story’s allegorical meaning?

Diary of a Madman

Two brothers, whose names I need not mention here, were both good friends of mine in high school; but after a separation of many years we gradually lost touch. Some time ago I happened to hear that one of them was seriously ill, and since I was going back to my old home I broke my journey to call on them, I saw only one, however, who told me that the invalid was his younger brother.

“I appreciate your coming such a long way to see us,” he said, “but my brother recovered some time ago and has gone elsewhere to take up an official post.” Then, laughing, he produced two volumes of his brother’s diary, saying that from these the nature of his past illness could be seen, and that there was no harm in showing them to an old friend. I took the diary away, read it through, and found that he had suffered from a form of persecution complex. The writing was most confused and incoherent, and he had made many wild statements; moreover he had omitted to give any dates, so that only by the colour of the ink and the differences in the writing could one tell that it was not written at one time. Certain sections, however, were not altogether disconnected, and I have copied out a part to serve as a subject for medical research. I have not altered a single illogicality in the diary and have changed only the names, even though the people referred to are all country folk, unknown to the world and of no consequence. As for the title, it was chosen by the diarist himself after his recovery, and I did not change it.

I

Tonight the moon is very bright.

I have not seen it for over thirty years, so today when I saw it I felt in unusually high spirits. I begin to realize that during the past thirty-odd years I have been in the dark; but now I must be extremely careful. Otherwise why should that dog at the Chao house have looked at me twice?

I have reason for my fear.

II

Tonight there is no moon at all, I know that this bodes ill. This morning when I went out cautiously, Mr. Chao had a strange look in his eyes, as if he were afraid of me, as if he wanted to murder me. There were seven or eight others, who discussed me in a whisper. And they were afraid of my seeing them. All the people I passed were like that. The fiercest among them grinned at me; whereupon I shivered from head to foot, knowing that their preparations were complete.

I was not afraid, however, but continued on my way. A group of children in front were also discussing me, and the look in their eyes was just like that in Mr. Chao’s while their faces too were ghastly pale. I wondered what grudge these children could have against me to make them behave like this. I could not help calling out: “Tell me!” But then they ran away.

I wonder what grudge Mr. Chao can have against me, what grudge the people on the road can have against me. I can think of nothing except that twenty years ago I trod on Mr. Ku Chiu’s account sheets for many years past, and Mr. Ku was very displeased. Although Mr. Chao does not know him, he must have heard talk of this and decided to avenge him, so he is conspiring against me with the people on the road, But then what of the children? At that time they were not yet born, so why should they eye me so strangely today, as if they were afraid of me, as if they wanted to murder me? This really frightens me, it is so bewildering and upsetting.

I know. They must have learned this from their parents!

III

I can’t sleep at night. Everything requires careful consideration if one is to understand it.

Those people, some of whom have been pilloried by the magistrate, slapped in the face by the local gentry, had their wives taken away by bailiffs, or their parents driven to suicide by creditors, never looked as frightened and as fierce then as they did yesterday.

The most extraordinary thing was that woman on the street yesterday who spanked her son and said, “Little devil! I’d like to bite several mouthfuls out of you to work off my feelings!” Yet all the time she looked at me. I gave a start, unable to control myself; then all those green-faced, long-toothed people began to laugh derisively. Old Chen hurried forward and dragged me home.

He dragged me home. The folk at home all pretended not to know me; they had the same look in their eyes as all the others. When I went into the study, they locked the door outside as if cooping up a chicken or a duck. This incident left me even more bewildered.

A few days ago a tenant of ours from Wolf Cub Village came to report the failure of the crops, and told my elder brother that a notorious character in their village had been beaten to death; then some people had taken out his heart and liver, fried them in oil and eaten them, as a means of increasing their courage. When I interrupted, the tenant and my brother both stared at me. Only today have I realized that they had exactly the same look in their eyes as those people outside.

Just to think of it sets me shivering from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet.

They eat human beings, so they may eat me.

I see that woman’s “bite several mouthfuls out of you,” the laughter of those green-faced, long-toothed people and the tenant’s story the other day are obviously secret signs. I realize all the poison in their speech, all the daggers in their laughter. Their teeth are white and glistening: they are all man-eaters.

It seems to me, although I am not a bad man, ever since I trod on Mr. Ku’s accounts it has been touch-and-go. They seem to have secrets which I cannot guess, and once they are angry they will call anyone a bad character. I remember when my elder brother taught me to write compositions, no matter how good a man was, if I produced arguments to the contrary he would mark that passage to show his approval; while if I excused evil-doers, he would say: “Good for you, that shows originality.” How can I possibly guess their secret thoughts—especially when they are ready to eat people?

Everything requires careful consideration if one is to understand it. In ancient times, as I recollect, people often ate human beings, but I am rather hazy about it. I tried to look this up, but my history has no chronology, and scrawled all over each page are the words: “Virtue and Morality.” Since I could not sleep anyway, I read intently half the night, until I began to see words between the lines, the whole book being filled with the two words—”Eat people.”

All these words written in the book, all the words spoken by our tenant, gaze at me strangely with an enigmatic smile.

I too am a man, and they want to eat me!

IV

In the morning I sat quietly for some time. Old Chen brought lunch in: one bowl of vegetables, one bowl of steamed fish. The eyes of the fish were white and hard, and its mouth was open just like those people who want to eat human beings. After a few mouthfuls I could not tell whether the slippery morsels were fish or human flesh, so I brought it all up.

I said, “Old Chen, tell my brother that I feel quite suffocated, and want to have a stroll in the garden.” Old Chen said nothing but went out, and presently he came back and opened the gate.

I did not move, but watched to see how they would treat me, feeling certain that they would not let me go. Sure enough! My elder brother came slowly out, leading an old man. There was a murderous gleam in his eyes, and fearing that I would see it he lowered his head, stealing glances at me from the side of his spectacles.

“You seem to be very well today,” said my brother.

“Yes,” said I.

“I have invited Mr. Ho here today,” said my brother, “to examine you.”

“All right,” said I. Actually I knew quite well that this old man was the executioner in disguise! He simply used the pretext of feeling my pulse to see how fat I was; for by so doing he would receive a share of my flesh. Still I was not afraid. Although I do not eat men, my courage is greater than theirs. I held out my two fists, to see what he would do. The old man sat down, closed his eyes, fumbled for some time and remained still for some time; then he opened his shifty eyes and said, “Don’t let your imagination run away with you. Rest quietly for a few days, and you will be all right.”

Don’t let your imagination run away with you! Rest quietly for a few days! When I have grown fat, naturally they will have more to eat; but what good will it do me, or how can it be “all right”? All these people wanting to eat human flesh and at the same time stealthily trying to keep up appearances, not daring to act promptly, really made me nearly die of laughter. I could not help roaring with laughter, I was so amused. I knew that in this laughter were courage and integrity. Both the old man and my brother turned pale, awed by my courage and integrity.

But just because I am brave they are the more eager to eat me, in order to acquire some of my courage. The old man went out of the gate, but before he had gone far he said to my brother in a low voice, “To be eaten at once!” And my brother nodded. So you are in it too! This stupendous discovery, although it came as a shock, is yet no more than I had expected: the accomplice in eating me is my elder brother!

The eater of human flesh is my elder brother!

I am the younger brother of an eater of human flesh!

I myself will be eaten by others, but none the less I am the younger brother of an eater of human flesh!

V

These few days I have been thinking again: suppose that old man were not an executioner in disguise, but a real doctor; he would be none the less an eater of human flesh. In that book on herbs, written by his predecessor Li Shih-chen, it is clearly stated that men’s flesh can he boiled and eaten; so can he still say that he does not eat men?

As for my elder brother, I have also good reason to suspect him. When he was teaching me, he said with his own lips, “People exchange their sons to eat.” And once in discussing a bad man, he said that not only did he deserve to be killed, he should “have his flesh eaten and his hide slept on. . . .” I was still young then, and my heart beat faster for some time, he was not at all surprised by the story that our tenant from Wolf Cub Village told us the other day about eating a man’s heart and liver, but kept nodding his head. He is evidently just as cruel as before. Since it is possible to “exchange sons to eat,” then anything can be exchanged, anyone can be eaten. In the past I simply listened to his explanations, and let it go at that; now I know that when he explained it to me, not only was there human fat at the corner of his lips, but his whole heart was set on eating men.

VI

Pitch dark. I don’t know whether it is day or night. The Chao family dog has started barking again.

The fierceness of a lion, the timidity of a rabbit, the craftiness of a fox. . . .

VII

I know their way; they are not willing to kill anyone outright, nor do they dare, for fear of the consequences. Instead they have banded together and set traps everywhere, to force me to kill myself. The behaviour of the men and women in the street a few days ago, and my elder brother’s attitude these last few days, make it quite obvious. What they like best is for a man to take off his belt, and hang himself from a beam; for then they can enjoy their heart’s desire without being blamed for murder. Naturally that sets them roaring with delighted laughter. On the other hand, if a man is frightened or worried to death, although that makes him rather thin, they still nod in approval.

They only eat dead flesh! I remember reading somewhere of a hideous beast, with an ugly look in its eye, called “hyena” which often eats dead flesh. Even the largest bones it grinds into fragments and swallows: the mere thought of this is enough to terrify one. Hyenas are related to wolves, and wolves belong to the canine species. The other day the dog in the Chao house looked at me several times; obviously it is in the plot too and has become their accomplice. The old man’s eyes were cast down, but that did not deceive me!

The most deplorable is my elder brother. He is also a man, so why is he not afraid, why is he plotting with others to eat me? Is it that when one is used to it he no longer thinks it a crime? Or is it that he has hardened his heart to do something he knows is wrong?

In cursing man-eaters, I shall start with my brother, and in dissuading man-eaters, I shall start with him too.

VIII

Actually, such arguments should have convinced them long ago. . . .

Suddenly someone came in. He was only about twenty years old and I did not see his features very clearly. His face was wreathed in smiles, but when he nodded to me his smile did not seem genuine. I asked him “Is it right to eat human beings?”

Still smiling, he replied, “When there is no famine how can one eat human beings?”

I realized at once, he was one of them; but still I summoned up courage to repeat my question:

“Is it right?”

“What makes you ask such a thing? You really are . . fond of a joke. . . . It is very fine today.”

“It is fine, and the moon is very bright. But I want to ask you: Is it right?”

He looked disconcerted, and muttered: “No….”

“No? Then why do they still do it?”

“What are you talking about?”

“What am I talking about? They are eating men now in Wolf Cub Village, and you can see it written all over the books, in fresh red ink.”

His expression changed, and he grew ghastly pale. “It may be so,” he said, staring at me. “It has always been like that. . . .”

“Is it right because it has always been like that?”

“I refuse to discuss these things with you. Anyway, you shouldn’t talk about it. Whoever talks about it is in the wrong!”

I leaped up and opened my eyes wide, but the man had vanished. I was soaked with perspiration. He was much younger than my elder brother, but even so he was in it. He must have been taught by his parents. And I am afraid he has already taught his son: that is why even the children look at me so fiercely.

IX

Wanting to eat men, at the same time afraid of being eaten themselves, they all look at each other with the deepest suspicion. . . .

How comfortable life would be for them if they could rid themselves of such obsessions and go to work, walk, eat and sleep at ease. They have only this one step to take. Yet fathers and sons, husbands and wives, brothers, friends, teachers and students, sworn enemies and even strangers, have all joined in this conspiracy, discouraging and preventing each other from taking this step.

X

Early this morning I went to look for my elder brother. He was standing outside the hall door looking at the sky, when I walked up behind him, stood between him and the door, and with exceptional poise and politeness said to him:

“Brother, I have something to say to you.”

“Well, what is it?” he asked, quickly turning towards me and nodding.

“It is very little, but I find it difficult to say. Brother, probably all primitive people ate a little human flesh to begin with. Later, because their outlook changed, some of them stopped, and because they tried to be good they changed into men, changed into real men. But some are still eating—just like reptiles. Some have changed into fish, birds, monkeys and finally men; but some do not try to be good and remain reptiles still. When those who eat men compare themselves with those who do not, how ashamed they must be. Probably much more ashamed than the reptiles are before monkeys.

“In ancient times Yi Ya boiled his son for Chieh and Chou to eat; that is the old story. But actually since the creation of heaven and earth by Pan Ku men have been eating each other, from the time of Yi Ya’s son to the time of Hsu Hsi-lin, and from the time of Hsu Hsi-lin down to the man caught in Wolf Cub Village. Last year they executed a criminal in the city, and a consumptive soaked a piece of bread in his blood and sucked it.

“They want to eat me, and of course you can do nothing about it single-handed; but why should you join them? As man-eaters they are capable of anything. If they eat me, they can eat you as well; members of the same group can still eat each other. But if you will just change your ways immediately, then everyone will have peace. Although this has been going on since time immemorial, today we could make a special effort to be good, and say this is not to be done! I’m sure you can say so, brother. The other day when the tenant wanted the rent reduced, you said it couldn’t be done.”

At first he only smiled cynically, then a murderous gleam came into his eyes, and when I spoke of their secret his face turned pale. Outside the gate stood a group of people, including Mr. Chao and his dog, all craning their necks to peer in. I could not see all their faces, for they seemed to be masked in cloths; some of them looked pale and ghastly still, concealing their laughter. I knew they were one band, all eaters of human flesh. But I also knew that they did not all think alike by any means. Some of them thought that since it had always been so, men should be eaten. Some of them knew that they should not eat men, but still wanted to; and they were afraid people might discover their secret; thus when they heard me they became angry, but they still smiled their. cynical, tight-lipped smile.

Suddenly my brother looked furious, and shouted in a loud voice:

“Get out of here, all of you! What is the point of looking at a madman?”

Then I realized part of their cunning. They would never be willing to change their stand, and their plans were all laid; they had stigmatized me as a madman. In future when I was eaten, not only would there be no trouble, but people would probably be grateful to them. When our tenant spoke of the villagers eating a bad character, it was exactly the same device. This is their old trick.

Old Chen came in too, in a great temper, but they could not stop my mouth, I had to speak to those people:

“You should change, change from the bottom of your hearts!” I said. “You most know that in future there will be no place for man-eaters in the world.

“If you don’t change, you may all be eaten by each other. Although so many are born, they will be wiped out by the real men, just like wolves killed by hunters. Just like reptiles!”

Old Chen drove everybody away. My brother had disappeared. Old Chen advised me to go back to my room. The room was pitch dark. The beams and rafters shook above my head. After shaking for some time they grew larger. They piled on top of me.

The weight was so great, I could not move. They meant that I should die. I knew that the weight was false, so I struggled out, covered in perspiration. But I had to say:

“You should change at once, change from the bottom of your hearts! You must know that in future there will be no place for man-eaters in the world . . . .”

XI

The sun does not shine, the door is not opened, every day two meals.

I took up my chopsticks, then thought of my elder brother; I know now how my little sister died: it was all through him. My sister was only five at the time. I can still remember how lovable and pathetic she looked. Mother cried and cried, but he begged her not to cry, probably because he had eaten her himself, and so her crying made him feel ashamed. If he had any sense of shame. . . .

My sister was eaten by my brother, but I don’t know whether mother realized it or not.

I think mother must have known, but when she cried she did not say so outright, probably because she thought it proper too. I remember when I was four or five years old, sitting in the cool of the hall, my brother told me that if a man’s parents were ill, he should cut off a piece of his flesh and boil it for them if he wanted to be considered a good son; and mother did not contradict him. If one piece could be eaten, obviously so could the whole. And yet just to think of the mourning then still makes my heart bleed; that is the extraordinary thing about it!

XII

I can’t bear to think of it.

I have only just realized that I have been living all these years in a place where for four thousand years they have been eating human flesh. My brother had just taken over the charge of the house when our sister died, and he may well have used her flesh in our rice and dishes, making us eat it unwittingly.

It is possible that I ate several pieces of my sister’s flesh unwittingly, and now it is my turn, . . .

How can a man like myself, after four thousand years of man-caring history—even though I knew nothing about it at first—ever hope to face real men?

XIII

Perhaps there are still children who have not eaten men? Save the children. . . .

Ryunosuke Akutagawa- “In A Grove”

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (surname: Akutagawa), the so-called “father of the Japanese short story,” wrote a series of stories derived from Japan’s past (largely, 12th- and 13th-century Japanese tales) but inflected with a modern psychological perspective. He studied English literature at Tokyo Imperial University, which is now the University of Tokyo. His writing draws from diverse sources, such as Chinese, Japanese, and European materials and culture. As a writer, he received encouragement from Natsume Sōseki, a renowned Japanese novelist of his time. Many of his powerful stories, which often have chilling themes, have been turned into films. His short stories, “Rashomon” (1915) and “In a Grove” (1922), for example, were adapted into the single film Rashomon (1950), directed by Akira Kurosawa. Kurosawa’s film reflects the dismal worldview of the servant in the story “Rashomon” and also incorporates the general setting of the same short story—the decline of the Heian era (794-1185). (The Rashomon—”mon” meaning “gate”—refers to the southern entry gate to the city of Kyoto during the Heian era.) On the other hand, “In a Grove,” also a story set in the late Heian period, narrates the murder of a samurai named Takehiro from multiple characters’ perspectives in a modernist style. “In a Grove” is the short story that fuels the main narrative of Kurosawa’s film. Although Akutagawa had a brief life (suicide at age thirty five), his many stories are influential around the world.

Consider while reading:

- In “In a Grove,” which characters claim to have killed the dead man (Takehiro)? If you were to pick one character, who do you think actually killed Takehiro, or do you think it was a suicide? Pick the most likely person to have killed Takehiro and provide supporting ideas from the text. At the same time, consider the reasons why your view might be doubted.

- Do any of these testimonies and confessions seem to go along with, or go against, any stereotypes or biases related to gender or social status? Explain.

- What do these contradictory testimonies and confessions say about the nature of truth, memory, and/or morality?

“In A Grove”

The Testimony of a Woodcutter Questioned

by a High Police Commissioner

Yes, sir. Certainly, it was I who found the body. This morning, as usual, I went to cut my daily quota of cedars, when I found the body in a grove in a hollow in the mountains. The exact location? About 150 meters off the Yamashina stage road. It’s an out-of-the-way grove of bamboo and cedars.

The body was lying flat on its back dressed in a bluish silk kimono and a wrinkled head-dress of the Kyoto style. A single sword-stroke had pierced the breast. The fallen bamboo-blades around it were stained with bloody blossoms. No, the blood was no longer running. The wound had dried up, I believe. And also, a gad-fly was stuck fast there, hardly noticing my footsteps.

You ask me if I saw a sword or any such thing?

No, nothing, sir. I found only a rope at the root of a cedar near by. And . . . well, in addition to a rope, I found a comb. That was all. Apparently he must have made a battle of it before he was murdered, because the grass and fallen bamboo-blades had been trampled down all around.

“A horse was near by?”

No, sir. It’s hard enough for a man to enter, let alone a horse.

The Testimony of a Traveling Buddhist Priest

Questioned by a High Police Commissioner

The time? Certainly, it was about noon yesterday, sir. The unfortunate man was on the road from Sekiyama to Yamashina. He was walking toward Sekiyama with a woman accompanying him on horseback, who I have since learned was his wife. A scarf hanging from her head hid her face from view. All I saw was the color of her clothes, a lilac-colored suit. Her horse was a sorrel with a fine mane. The lady’s height? Oh, about four feet five inches. Since I am a Buddhist priest, I took little notice about her details. Well, the man was armed with a sword as well as a bow and arrows. And I remember that he carried some twenty odd arrows in his quiver.

Little did I expect that he would meet such a fate. Truly human life is as evanescent as the morning dew or a flash of lightning. My words are inadequate to express my sympathy for him.

The Testimony of a Policeman

Questioned by a High Police Commissioner

The man that I arrested? He is a notorious brigand called Tajomaru. When I arrested him, he had fallen off his horse. He was groaning on the bridge at Awataguchi. The time? It was in the early hours of last night. For the record, I might say that the other day I tried to arrest him, but unfortunately he escaped. He was wearing a dark blue silk kimono and a large plain sword. And, as you see, he got a bow and arrows somewhere. You say that this bow and these arrows look like the ones owned by the dead man? Then Tajomaru must be the murderer. The bow wound with leather strips, the black lacquered quiver, the seventeen arrows with hawk feathers—these were all in his possession I believe. Yes, Sir, the horse is, as you say, a sorrel with a fine mane. A little beyond the stone bridge I found the horse grazing by the roadside, with his long rein dangling. Surely there is some providence in his having been thrown by the horse.

Of all the robbers prowling around Kyoto, this Tajomaru has given the most grief to the women in town. Last autumn a wife who came to the mountain back of the Pindora of the Toribe Temple, presumably to pay a visit, was murdered, along with a girl. It has been suspected that it was his doing. If this criminal murdered the man, you cannot tell what he may have done with the man’s wife. May it please your honor to look into this problem as well.

The Testimony of an Old Woman

Questioned by a High Police Commissioner

Yes, sir, that corpse is the man who married my daughter. He does not come from Kyoto. He was a samurai in the town of Kokufu in the province of Wakasa. His name was Kanazawa no Takehiko, and his age was twenty-six. He was of a gentle disposition, so I am sure he did nothing to provoke the anger of others.

My daughter? Her name is Masago, and her age is nineteen. She is a spirited, fun-loving girl, but I am sure she has never known any man except Takehiko. She has a small, oval, dark-complected face with a mole at the corner of her left eye.

Yesterday Takehiko left for Wakasa with my daughter. What bad luck it is that things should have come to such a sad end! What has become of my daughter? I am resigned to giving up my son-in-law as lost, but the fate of my daughter worries me sick. For heaven’s sake leave no stone unturned to find her. I hate that robber Tajomaru, or whatever his name is. Not only my son-in-law, but my daughter . . . (Her later words were drowned in tears. )

Tajomaru’s Confession

I killed him, but not her. Where’s she gone? I can’t tell. Oh, wait a minute. No torture can make me confess what I don’t know. Now things have come to such a head, I won’t keep anything from you.

Yesterday a little past noon I met that couple. Just then a puff of wind blew, and raised her hanging scarf, so that I caught a glimpse of her face. Instantly it was again covered from my view. That may have been one reason; she looked like a Bodhisattva. At that moment I made up my mind to capture her even if I had to kill her man.

Why? To me killing isn’t a matter of such great consequence as you might think. When a woman is captured, her man has to be killed anyway. In killing, I use the sword I wear at my side. Am I the only one who kills people? You, you don’t use your swords. You kill people with your power, with your money. Sometimes you kill them on the pretext of working for their good. It’s true they don’t bleed. They are in the best of health, but all the same you’ve killed them. It’s hard to say who is a greater sinner, you or me. (An ironical smile. )

But it would be good if I could capture a woman without killing her man. So, I made up my mind to capture her, and do my best not to kill him. But it’s out of the question on the Yamashina stage road. So I managed to lure the couple into the mountains.

It was quite easy. I became their traveling companion, and I told them there was an old mound in the mountain over there, and that I had dug it open and found many mirrors and swords. I went on to tell them I’d buried the things in a grove behind the mountain, and that I’d like to sell them at a low price to anyone who would care to have them. Then . . . you see, isn’t greed terrible? He was beginning to be moved by my talk before he knew it. In less than half an hour they were driving their horse toward the mountain with me.

When he came in front of the grove, I told them that the treasures were buried in it, and I asked them to come and see. The man had no objection—he was blinded by greed. The woman said she would wait on horseback. It was natural for her to say so, at the sight of a thick grove. To tell you the truth, my plan worked just as I wished, so I went into the grove with him, leaving her behind alone.

The grove is only bamboo for some distance. About fifty yards ahead there’s a rather open clump of cedars. It was a convenient spot for my purpose. Pushing my way through the grove, I told him a plausible lie that the treasures were buried under the cedars. When I told him this, he pushed his laborious way toward the slender cedar visible through the grove. After a while the bamboo thinned out, and we came to where a number of cedars grew in a row. As soon as we got there, I seized him from behind. Because he was a trained, sword-bearing warrior, he was quite strong, but he was taken by surprise, so there was no help for him. I soon tied him up to the root of a cedar. Where did I get a rope? Thank heaven, being a robber, I had a rope with me, since I might have to scale a wall at any moment. Of course it was easy to stop him from calling out by gagging his mouth with fallen bamboo leaves.

When I disposed of him, I went to his woman and asked her to come and see him, because he seemed to have been suddenly taken sick. It’s needless to say that this plan also worked well. The woman, her sedge hat off, came into the depths of the grove, where I led her by the hand. The instant she caught sight of her husband, she drew a small sword. I’ve never seen a woman of such violent temper. If I’d been off guard, I’d have got a thrust in my side. I dodged, but she kept on slashing at me. She might have wounded me deeply or killed me. But I’m Tajomaru. I managed to strike down her small sword without drawing my own. The most spirited woman is defenseless without a weapon. At least I could satisfy my desire for her without taking her husband’s life.

Yes . . . without taking his life. I had no wish to kill him. I was about to run away from the grove, leaving the woman behind in tears, when she frantically clung to my arm. In broken fragments of words, she asked that either her husband or I die. She said it was more trying than death to have her shame known to two men. She gasped out that she wanted to be the wife of whichever survived. Then a furious desire to kill him seized me. (Gloomy excitement. )

Telling you in this way, no doubt I seem a crueler man than you. But that’s because you didn’t see her face. Especially her burning eyes at that moment. As I saw her eye to eye, I wanted to make her my wife even if I were to be struck by lightning. I wanted to make her my wife . . . this single desire filled my mind. This was not only lust, as you might think. At that time if I’d had no other desire than lust, I’d surely not have minded knocking her down and running away. Then I wouldn’t have stained my sword with his blood. But the moment I gazed at her face in the dark grove, I decided not to leave there without killing him.

But I didn’t like to resort to unfair means to kill him. I untied him and told him to cross swords with me. (The rope that was found at the root of the cedar is the rope I dropped at the time. ) Furious with anger, he drew his thick sword. And quick as thought, he sprang at me ferociously, without speaking a word. I needn’t tell you how our fight turned out. The twenty-third stroke . . . please remember this. I’m impressed with this fact still. Nobody under the sun has ever clashed swords with me twenty strokes. (A cheerful smile. )

When he fell, I turned toward her, lowering my blood-stained sword. But to my great astonishment she was gone. I wondered to where she had run away. I looked for her in the clump of cedars. I listened, but heard only a groaning sound from the throat of the dying man.

As soon as we started to cross swords, she may have run away through the grove to call for help. When I thought of that, I decided it was a matter of life and death to me. So, robbing him of his sword, and bow and arrows, I ran out to the mountain road. There I found her horse still grazing quietly. It would be a mere waste of words to tell you the later details, but before I entered town I had already parted with the sword. That’s all my confession. I know that my head will be hung in chains anyway, so put me down for the maximum penalty. (A defiant attitude. )

The Confession of a Woman Who HasCome to the Shimizu Temple

That man in the blue silk kimono, after forcing me to yield to him, laughed mockingly as he looked at my bound husband. How horrified my husband must have been! But no matter how hard he struggled in agony, the rope cut into him all the more tightly. In spite of myself I ran stumblingly toward his side. Or rather I tried to run toward him, but the man instantly knocked me down. Just at that moment I saw an indescribable light in my husband’s eyes. Something beyond expression . . . his eyes make me shudder even now. That instantaneous look of my husband, who couldn’t speak a word, told me all his heart. The flash in his eyes was neither anger nor sorrow . . . only a cold light, a look of loathing. More struck by the look in his eyes than by the blow of the thief, I called out in spite of myself and fell unconscious.

In the course of time I came to, and found that the man in blue silk was gone. I saw only my husband still bound to the root of the cedar. I raised myself from the bamboo-blades with difficulty, and looked into his face; but the expression in his eyes was just the same as before.

Beneath the cold contempt in his eyes, there was hatred. Shame, grief, and anger . . . I don’t know how to express my heart at that time. Reeling to my feet, I went up to my husband.

“Takejiro,” I said to him, “since things have come to this pass, I cannot live with you. I’m determined to die . . . but you must die, too. You saw my shame. I can’t leave you alive as you are.”

This was all I could say. Still he went on gazing at me with loathing and contempt. My heart breaking, I looked for his sword. It must have been taken by the robber. Neither his sword nor his bow and arrows were to be seen in the grove. But fortunately my small sword was lying at my feet. Raising it over head, once more I said, “Now give me your life. I’ll follow you right away.”

When he heard these words, he moved his lips with difficulty. Since his mouth was stuffed with leaves, of course his voice could not be heard at all. But at a glance I understood his words. Despising me, his look said only, “Kill me.” Neither conscious nor unconscious, I stabbed the small sword through the lilac-colored kimono into his breast.

Again at this time I must have fainted. By the time I managed to look up, he had already breathed his last—still in bonds. A streak of sinking sunlight streamed through the clump of cedars and bamboos, and shone on his pale face. Gulping down my sobs, I untied the rope from his dead body. And . . . and what has become of me since I have no more strength to tell you. Anyway I hadn’t the strength to die. I stabbed my own throat with the small sword, I threw myself into a pond at the foot of the mountain, and I tried to kill myself in many ways. Unable to end my life, I am still living in dishonor. (A lonely smile. ) Worthless as I am, I must have been forsaken even by the most merciful Kwannon. I killed my own husband. I was violated by the robber. Whatever can I do? Whatever can I . . . I . . . (Gradually, violent sobbing. )

The Story of the Murdered Man,as Told Through a Medium

After violating my wife, the robber, sitting there, began to speak comforting words to her. Of course I couldn’t speak. My whole body was tied fast to the root of a cedar. But meanwhile I winked at her many times, as much as to say “Don’t believe the robber.” I wanted to convey some such meaning to her. But my wife, sitting dejectedly on the bamboo leaves, was looking hard at her lap. To all appearance, she was listening to his words. I was agonized by jealousy. In the meantime the robber went on with his clever talk, from one subject to another. The robber finally made his bold brazen proposal.”Once your virtue is stained, you won’t get along well with your husband, so won’t you be my wife instead? It’s my love for you that made me be violent toward you.”

While the criminal talked, my wife raised her face as if in a trance. She had never looked so beautiful as at that moment. What did my beautiful wife say in answer to him while I was sitting bound there? I am lost in space, but I have never thought of her answer without burning with anger and jealousy. Truly she said, . . .”Then take me away with you wherever you go.”

This is not the whole of her sin. If that were all, I would not be tormented so much in the dark. When she was going out of the grove as if in a dream, her hand in the robber’s, she suddenly turned pale, and pointed at me tied to the root of the cedar, and said, “Kill him! I cannot marry you as long as he lives.” “Kill him!” she cried many times, as if she had gone crazy. Even now these words threaten to blow me headlong into the bottomless abyss of darkness. Has such a hateful thing come out of a human mouth ever before? Have such cursed words ever struck a human ear, even once? Even once such a . . . (A sudden cry of scorn. ) At these words the robber himself turned pale.”Kill him,” she cried, clinging to his arms. Looking hard at her, he answered neither yes nor no . . . but hardly had I thought about his answer before she had been knocked down into the bamboo leaves. (Again a cry of scorn. ) Quietly folding his arms, he looked at me and said, “What will you do with her? Kill her or save her? You have only to nod. Kill her?” For these words alone I would like to pardon his crime.

While I hesitated, she shrieked and ran into the depths of the grove. The robber instantly snatched at her, but he failed even to grasp her sleeve.

After she ran away, he took up my sword, and my bow and arrows. With a single stroke he cut one of my bonds. I remember his mumbling, “My fate is next.” Then he disappeared from the grove. All was silent after that. No, I heard someone crying. Untying the rest of my bonds, I listened carefully, and I noticed that it was my own crying. (Long silence. )

I raised my exhausted body from the foot of the cedar. In front of me there was shining the small sword which my wife had dropped. I took it up and stabbed it into my breast. A bloody lump rose to my mouth, but I didn’t feel any pain. When my breast grew cold, everything was as silent as the dead in their graves. What profound silence! Not a single bird-note was heard in the sky over this grave in the hollow of the mountains. Only a lonely light lingered on the cedars and mountains. By and by the light gradually grew fainter, till the cedars and bamboo were lost to view. Lying there, I was enveloped in deep silence.

Then someone crept up to me. I tried to see who it was. But darkness had already been gathering round me. Someone. . . that someone drew the small sword softly out of my breast in its invisible hand. At the same time once more blood flowed into my mouth. And once and for all I sank down into the darkness of space.

See full version at Read In a Grove PAGE 5 by Ryunosuke Akutagawa | 25,629 Free Classic Stories and Poems | FullReads

Cho Se-hui

Cho Se-hui (surname: Cho) is a South Korean writer of the so-called “hangeul [the Korean alphabet] generation,” which refers to the first generation to be educated entirely in Korean, unlike the previous generations who received Japanese colonial education or studied Chinese primarily. Cho is most well-known for his novel A Little Ball Launched by a Dwarf (1978), which was initially published as a “linked novel”—a series of related short stories in several Korean magazines. “Knifeblade,” “A Little Ball Launched by a Dwarf,” and “The Möbius Strip” are parts of this novel, which is noted for its sharp allegorical social criticism of South Korea in the 1970s.

Written during the Park Chung-hee authoritarian regime (1961-1979), when South Korea was undergoing rapid industrialization, the novel focuses on the forced redevelopment of Seoul in the 1970s and asks at what human cost the economic development has taken place. Written in concise and accessible language and with the use of irony, the novel brings social contradictions, labor issues under capitalism, and the relationship between the haves and have-nots to the fore. The English translation of the novel, titled The Dwarf, by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton was published in 2006. Cho’s other works include Time Travel (1983) and Root of Silence (1985).

Read the entirety of “Knifeblade”, “Little Ball Launched by Dwarf” and “Mobius Strip” here: content (sogang.ac.kr)

Haruki Murakami- The Second Bakery Attack

“The Second Bakery Attack” is a short story by Murakami Haruki (surname: Murakami), a critically acclaimed and popular Japanese writer. This short story, first published in English in Playboy magazine in 1985, is also part of The Elephant Vanishes (1993), a collection of Murakami’s seventeen short stories in English translation. “The Second Bakery Attack” displays many of Murakami’s signature styles and approaches, such as mixing realism and surrealism (or magical realism), the use of interior monologue, allusions to popular culture and Western culture, and postmodernist elements. Along with the metaphor of the insatiable hunger the couple feels, what is noteworthy in the story is the newly married couple’s changing gender dynamics upon the (partial) release of the husband’s “secret,” and the impact on the husband’s psychology of these gender dynamics. Murakami’s other notable works include Men without Women (2014), IQ84 (2009-10), Kafka on the Shore (2002), The Wind-up Bird Chronicle (1994-95), Norwegian Wood (1987), and A Wild Sheep Chase (1982). Many of his works have been translated into English (and their publication years are different from the original publication years listed above) by such translators as Philip Gabriel, Jay Rubin, and Alfred Birnbaum. Murakami is also a translator himself, having translated Western literary works into Japanese.

The Second Bakery Attack

I’m still not sure I made the right choice when I told my wife about the bakery attack. But then, it might not have been a question of right and wrong. Which is to say that wrong choices can produce right results, and vice versa. I myself have adopted the position that, in fact, we never choose anything at all. Things happen. Or not.

If you look at it this way, it just so happens that I told my wife about the bakery attack. I hadn’t been planning to bring it up–I had forgotten all about it–but it wasn’t one of those now-that-you-mention-it kind of things, either.

What reminded me of the bakery attack was an unbearable hunger. It hit just before two o’clock in the morning. We had eaten a light supper at six, crawled into bed at nine-thirty, and gone to sleep. For some reason, we woke up at exactly the same moment. A few minutes later, the pangs struck with the force of the tornado in The Wizard of Oz. These were tremendous, overpowering hunger pangs.

Our refrigerator contained not a single item that could be technically categorized as food. We had a bottle of French dressing, six cans of beer, two shriveled onions, a sitck of butter, and a box of refrigerator deodorizer. With only two weeks of married life behind us, we had yet to establish a precise conjugal understanding with regard to the rules of dietary behavior. Let alone anything else.

I had a job in a law firm at the time, and she was doing secretarial work at a design school. I was either twenty-eight or twenty-nine–why can’t I remember the exact year we married?–and she was two years and eight months younger. Groceries were the last things on our minds.

We both felt too hungry to go back to sleep, but it hurt just to lie there. On the other hand, we were also too hungry to do anything useful. We got out of bed an ddrifted into the kitchen, ending up across the table from each other. What could have caused such violent hunger pangs?

We took turns opening the refrigerator door and hoping, but no matter how many times we looked inside, the contents never changed. Beer and onions and butter and dressing and deodorizer. It might have been possible to sauté the onions in the butter, but there was no chance those two shriveled onions could fill our empty stomachs. Onions are meant to be eaten with other things. They are not the kind of food you use to satisfy an appetite.

“Would madame care for some French dressing sautéed in deodorizer?”

I expected her to ignore my attempt at humor, and she did. “Let’s get in the car and look for an all-night restaurant,” I said. “There must be one on the highway.”

She rejected that suggestion. “We can’t. You’re not supposed to go out to eat after midnight.” She was old-fashioned that way.

I breathed once and said, “I guess not.”

Whenever my wife expressed such an opinion (or thesis) back then, it reverberated in my ears with the authority of a revelation. Maybe that’s what happens with newlyweds, I don’t know. But when she said this to me, I began to think that this was a special hunger, not one that could be satisfied through the mere expedient of taking it to an all-night restaurant on the highway.

A special kind of hunger. And what might that be?

I can present it here in the form of a cinematic image.

One, I am in a little boat, floating on a quiet sea. Two, I look down, and in the water I see the peak of a volcano thrusting up from the ocean floor. Three, the peak seems pretty close to the water’s surface, but just how close I cannot tell. Four, this is because the hypertransparency of the water interferes with the perception of distance.

This is a fairly accurate description of the image that arose in my mind during the two or three seconds between the time my wife said she refused to go to an all-night restaurant and I agreed with my “I guess not.” Not being Sigmund Freud, I was, of course, unable to analyze with any precision what this image signified, but I knew intuitively that it was a revelation. Which is why–the almost grotesque intensity of my hunger notwithstanding–I all but automatically agreed with her thesis (or declaration).

We did the only thing we could do: opened the beer. It was a lot better than eating those onions. She didn’t like beer much, so we divided the cans, two for her, four for me. While I was drinking the first one, she searched the kitchen shelves like a squirrel in November. Eventually, she turned up a package that had four butter cookies in the bottom. They were leftovers, soft and soggy, but we each ate two, savoring every crumb.

It was no use. Upon this hunger of ours, as vast and boundless as the Sinai Peninsula, the butter cookies and beer left not a trace.

Time oozed through the dark like a lead weight in a fish’s gut. I read the print on the aluminum beer cans. I stared at my watch. I looked at the refrigerator door. I turned the pages of yesterday’s paper. I used the edge of a postcard to scrape together the cookie crumbs on the tabletop.

“I’ve never been this hungry in my whole life,” she said. “I wonder if it has anything to do with being married.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Or maybe not.”

While she hunted for more fragments of food, I leaned over the edge of my boat and looked down at the peak of the underwater volcano. The clarity of the ocean water all around the boat gave me an unsettled feeling, as if a hollow had opened somewhere behind my solar plexus–a hermetically sealed cavern that had neither entrance nor exit. Something about this weird sense of absence–this sense of the existential reality of non-existence–resembled the paralyzing fear you might feel when you climb to the very top of a high steeple. This connection between hunger and acrophobia was a new discovery for me.

Which is when it occurred to me that I had once before had this same kind of experience. My stomach had been just as empty then….When?…Oh, sure, that was–

“The time of the bakery attack,” I heard myself saying.

“The bakery attack? What are you talking about?”

And so it started.

“I once attached a bakery. Long time ago. Not a big bakery. Not famous. The bread was nothing special. Not bad, either. One of those ordinary little neighborhood bakeries right in the middle of a block of shops. Some old guy ran it who did everything himself. Baked in the morning, and when he sold out, he closed up for the day.”

“If you were going to attack a bakery, why that one?”

“Well, there was no point in attacking a big bakery. All we wanted was bread, not money. We were attackers, not robbers.”

“We? Who’s we?”

“My best friend back then. Ten years ago. We were so broke we couldn’t buy toothpaste. Never had enough food. We did some pretty awful things to get our hands on food. The bakery attack was one.”

“I don’t get it.” She looked hard at me. Her eyes could have been searching for a faded star in the morning sky. “Why didn’t you get a job? You could have worked after school. That would have been easier than attacking bakeries.”

“We didn’t want to work. We were absolutely clear on that.”

“Well, you’re working now, aren’t you?”

I nodded and sucked some more beer. Then I rubbed my eyes. A kind of beery mud had oozed into my brain and was struggling with my hunger pangs.

“Times change. People change,” I said. “Let’s go back to bed. We’ve got to get up early.”

“I’m not sleepy. I want you to tell me about the bakery attack.”

“There’s nothing to tell. No action. No excitement.”

“Was it a success?”

I gave up on sleep and ripped open another beer. Once she gets interested in a story, she has to hear it all the way through. That’s just the way she is.

“Well, it was kind of a success. And kind of not. We got what we wanted. But as a holdup, it didn’t work. The baker gave us the bread before we could take it from him.”

“Free?”

“Not exactly, no. That’s the hard part.” I shook my head. “The baker was a classical-music freak, and when we got there, he was listening to an album of Wagner overtures. So he made us a deal. If we would listen to the record all the way through, we could take as much bread as we liked. I talked it over with my buddy and we figured, Okay. It wouldn’t be work in the purest sense of the word, and it wouldn’t hurt anybody. So we put our knives back in our bag, pulled up a couple of chairs, and listened to the overtures to Tannhäuser and The Flying Dutchman.”

“And after that, you got your bread?”

“Right. Most of what he had in the shop. Stuffed it in our bag and took it home. Kept us fed for maybe four or five days.” I took another sip. Like soundless waves from an undersea earthquake, my sleepiness gave my boat a long, slow rocking.

“Of course, we accomplished our mission. We got the bread. But you couldn’t say we had committed a crime. It was more of an exchange. We listened to Wagner with him, and in return, we got our bread. Legally speaking, it was more like a commercial transaction.”

“But listening to Wagner is not work,” she said.

“Oh, no, absolutely not. If the baker had insisted that we wash his dishes or clean his windows or something, we would have turned him down. But he didn’t. All he wanted from us was to listen to his Wagner LP from beginning to end. Nobody could have anticipated that. I mean–Wagner? It was like the baker put a curse on us. Now that I think of it, we should have refused. We should have threatened him with our knives and taken the damn bread. Then there wouldn’t have been any problem.”

“You had a problem?”

I rubbed my eyes again.

“Sort of. Nothing you could put your finger on. But things started to change after that. It was kind of a turning point. Like, I went back to the university, and I graduated, and I started working for the firm and studying for the bar exam, and I met you and got married. I never did anything like that again. No more bakery attacks.”

“That’s it?”

“Yup, that’s all there was to it.” I drank the last of the beer. Now all six cans were gone. Six pull-tabs lay in the ashtray like scales from a mermaid.

Of course, it wasn’t true that nothing had happened as a result of the bakery attack. There were plenty of things that you could easily have put your finger on, but I didn’t want to talk about them with her.

“So, this friend of yours, what’s he doing now?”

“I have no idea. Something happened, some nothing kind of thing, and we stopped hanging around together. I haven’t seen him since. I don’t know what he’s doing.”

For a while, she didn’t speak. She probably sensed that I wasn’t telling her the whole story. But she wasn’t ready to press me on it.

“Still,” she said, “that’s why you two broke up, isn’t it? The bakery attack was the direct cause.”

“Maybe so. I guess it was more intense than either of us realized. We talked about the relationship of bread to Wagner for days after that. We kept asking ourselves if we had made the right choice. We couldn’t decide. Of course, if you look at it sensibly, we did make the right choice. Nobody got hurt. Everybody got what he wanted. The baker–I still can’t figure out why he did what he did–but anyway, he succeeded with his Wagner propaganda. And we succeeded in stuffing our faces with bread.

“But even so, we had this feeling that we had made a terrible mistake. And somehow, this mistake has just stayed there, unresolved, casting a dark shadow on our lives. That’s why I used the word ‘curse.’ It’s true. It was like a curse.”

“Do you think you still have it?”

I took the six pull-tabs from the ashtray and arranged them into an aluminum ring the size of a bracelet.

“Who knows? I don’t know. I bet the world is full of curses. It’s hard to tell which curse makes any one thing go wrong.”

“That’s not true.” She looked right at me. “You can tell, if you think about it. And unless you, yourself, personally break the curse, it’ll stick with you like a toothache. It’ll torture you till you die. And not just you. Me, too.”

“You?”

“Well, I’m your best friend now, aren’t I? Why do you think we’re both so hungry? I never, ever, once in my life felt a hunger like this until I married you. Don’t you think it’s abnormal? Your curse is working on me, too.”