17 CENTRAL ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Jainism

While Jainism dates as far back as the 6th-5th century BCE, it is placed in this time period because of its connections with the Ellora Temple, found below in the Architecture section. Understanding Jainism is integral for better understanding the overlap of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism in these cave temples.

The Jain faith’s primary concern is to purify and liberate the soul from the perpetual cycle of death and rebirth. The Jinas, practicing meditation and conforming to fundamental vows such as non-violence and truthfulness, have overcome attachment and desire and set the supreme example for all Jain followers. The path to liberation is defined by three main principles, the so-called three jewels of Jainism: right faith, right understanding and right conduct.

The Jain faith does not believe in a creator god like Hinduism or the Abrahamic faiths. In a way similar to Buddhists, the Jains venerate perfect ascetics who have been provided with valid authority on account of their career and abilities. They are named Jinas (‘Conquerors’) or Tirthaṃkaras (‘ford-makers’, because they have crossed to liberation) who provide ultimate models to the followers, the Jains. Mahavira was the twenty-fourth Jina. His predecessors are not historical figures, but this does not affect their place in respect and worship. Their existence lays emphasis on the idea of lineage which is at the center of Jainism. Mahavira is thus a continuator and a reformer rather than a founder, which he is often said to be.

All Jinas led similar lives. They were born as princes in royal families and withdrew from society in order to take up religious initiation, either before or after marriage, depending on the case.

The first stage of their ascetic life was full of tests that they had to overcome, showing their perseverance when faced with challenges. This spiritual evolution finally led to full enlightenment, known in Jainism as omniscience (kevalajñāna). When a Jina reaches this state they are then able to grasp everything everywhere whether it relates to past, present or future. They can then teach others the principles of the doctrine. This takes place during a general assembly where the Jina sits at the center, heard and seen by all beings wherever they are.

He then utters the divine sound which results in teaching expanded by him and his direct disciples, and builds around him a community of monks, nuns and lay followers. When his lifespan comes to an end and he has attained full perfection, the Jina leaves the human body for good and attains liberation from the cycle of rebirths.

The Jain faith can be best labelled as a path to liberation or a path of purification. This is defined as consisting of correct faith, correct understanding and correct conduct. The Jain teaching in its multiple shapes is an expansion of these ‘three jewels’, the sequence of which is significant and emphasizes a concern for rationality as one leads to the other: one can have a proper conduct only if one is aware of the proper way to analyze what exists.

Correct faith means recognizing the existence of nine verities or principles.

They are:

- the fact that there are sentient souls or living beings (jīva)

- the fact that there are non-sentient or material things (ajīva) such as time or space

- the fact that karma flows in the soul (āsrava)

- the fact that once in the soul karma is attached to it (bandha)

- the fact that there are forms of activity that are good (puṇya)

- the fact that there are forms of activity that are bad (pāpa)

- the fact that flowing of karma should be blocked (saṃvara)

- the fact that karma that has flowed in should be annihilated (nirjarā)

- the fact that once all karmas have been eliminated final liberation from the cycle of rebirths takes place (mokṣa)

This systematic worldview forms the basis for the Jains way of life and their religious practices.

Since the beginning, the Jain society has taken account of the fact there are two ways of life, a stricter one for ascetics and a milder one for non-ascetics, who live in the world engaged in professional and family life and are often called lay followers. Male and female mendicants, on the one hand, male and female lay followers, on the other hand, form the fourfold Jain community.

Monastic life is regarded as an ideal aim but Jainism has devised a lot of possibilities for lay people to live their faith earnestly in daily practice.

Jain mendicants are people who have become monks or nuns after the official initiation ceremony called dīkṣā. They renounce ordinary life, receive a new name and the monastic equipment in accordance with the monastic order to which they will belong. Then they lead a life of itinerancy, walking long distances and not using any mode of transportation as a general rule.

They conform to the ‘five great vows’ (mahāvratas) which provide a broad frame of behaviour.

- Non-violence (ahiṃsā)

- Truth (satya)

- Not taking what has not been given (asteya)

- Celibacy (brahmacarya)

- Non-attachment or non-possession (aparigraha)

The oldest division goes back to around the 1st century CE and remains the most important today. It produced the separation between the Śvetāmbaras and the Digambaras who hold various differences, the Digambaras being more strict in their practices and beliefs.

Digambaras

According to the Digambaras, a lot of teaching has been lost, but there were a few ascetics who could remember the essentials. One of them was Dharasena (ca. 137 CE) who transmitted them to his disciples, Puṣpadanta and Bhūtabali. They wrote the Teaching in six parts (Ṣaṭkhaṇḍāgama). Then another ascetic called Guṇabhadra wrote a Treatise on passion (Kaṣāyaprābhṛta). These large and complex treatises form the first authoritative works for the Digambaras. They provide technical expositions on cosmology, karma theory and the way karmic matter attaches to the soul as a result of desire and passions.

Śvetāmbaras

According to the Śvetāmbaras, the teaching was collected and put to writing in its final redaction during a collective recitation which took place in Valabhī (Gujarat) around 450 CE. This was led by Devarddhigaṇi Kṣamāśramaṇa. The teaching was organised in a set of texts divided into various categories (Angas, Upāngas, Chedasūtras, Mūlasūtras, Prakīrṇakas). A junior monk or nun starts with the basic texts (Mūlasūtras) and in time progresses to read more technical texts as he becomes more senior. The texts are varied; they are made up of prose and verse, and take the form of philosophical dialogues, poetry depicting ascetic life or exhorting ascetics to follow the ideal mendicant’s way of life, legends or parables, hymns to Mahavira and lists of concepts.

Within the scriptures, some groups of texts are unchanging while others show fluidity and divergences. The number of accepted scriptures among Śvetāmbaras corresponds to a sectarian division that took shape from the 15th century onwards. Mūrtipūjaks consider there to be forty-five scriptures while Sthānakavāsins and Terāpanthins state there are thirty-two.

In Mahavira’s time the prevalent sacred language was Sanskrit. It was associated with the Vedas, the earliest sacred texts of Hinduism, and with the brahmins, the religious elite in charge of their transmission. In contrast, Mahavira, like the Buddha, did not use Sanskrit as a preaching language, but Prakrit.

Contents and forms of the teaching

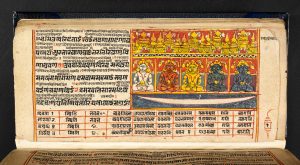

Jain teaching was thus fixed into writing in the middle of the 5th century CE, at the latest. It was available first in the form of hand-written manuscripts. Those which have come down to us, however, are not older than the end of the 11th century. Nothing before this time could be preserved due to the Indian climatic conditions. In

Northern India, manuscripts of Jain texts were first copied on palm-leaf and, from the 14th century onwards, on locally made paper. They were produced in large numbers in India and started entering European libraries in the last decades of the 19th century. The then India Office Library and British Museum were among the main institutions with collections of Jain manuscripts. The richness of Jain manuscript culture is a sign of the importance attached to scriptural knowledge (known as śrutajñāna) in this faith: knowledge being one of the three requisites for spiritual progress.

The fundamentals analyzed in canonical scriptures of both Jain groups are retold through concise definitions in That Which Is (Tattvārthasūtra), a Sanskrit handbook that has a special place in Jain tradition because it transcends the boundary between Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras and is recognized by both of them.

Copyright: World Religions: the Spirit Searching Copyright © 2021 by Jody L Ondich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

LITERATURE

ARCHITECTURE

Shore Temple

Seashore as canvas

Along the shores of one of the largest bays in the world, the Bay of Bengal, stands a temple complex that draws inspiration from the sea and its naturally occurring rock formations. The majestic Shore Temple (known locally as Alaivay-k-kovil) sits beside the sea in the small town of Mamallapuram in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. This complex of three separate shrines was constructed under the patronage of the Pallava king Nrasimhavarman II Rajasimha, who ascended the throne in 700 C.E. and ruled for about twenty years.

A temple in Dravidian style

Indian temple architecture can be broadly divided into two schools: the Nagara, or the North Indian tradition, and the Dravidian, or South Indian style of architecture. Both Nagara and Dravidian temples consist of a main shrine (vimana) which houses the inner sanctum known as grabha griha (literally “womb chamber”), topped by a pyramidal tower known as a sikhara. At the Shore Temple, the entire superstructure has an octagonal neck (griva) topped by a round stupi or finial. Dravidian temples are typically enclosed within an outer wall (prakara, shown below) with a large gateway tower known as a gopura.

The development of early Indian architecture demonstrates a progression from structures of wood and timber to cave shrines, rock cut structures, and eventually freestanding temples constructed out of mortar and stone. Cave shrines were dug into cliffs and hills and their scheme and ornamentation clearly exhibit the continuing influence of traditions used in earlier wooden structures. The rock cut temples were constructed out of large freestanding boulders that artists would work by carving the rocks from the top to the bottom on both the exterior and interior simultaneously.

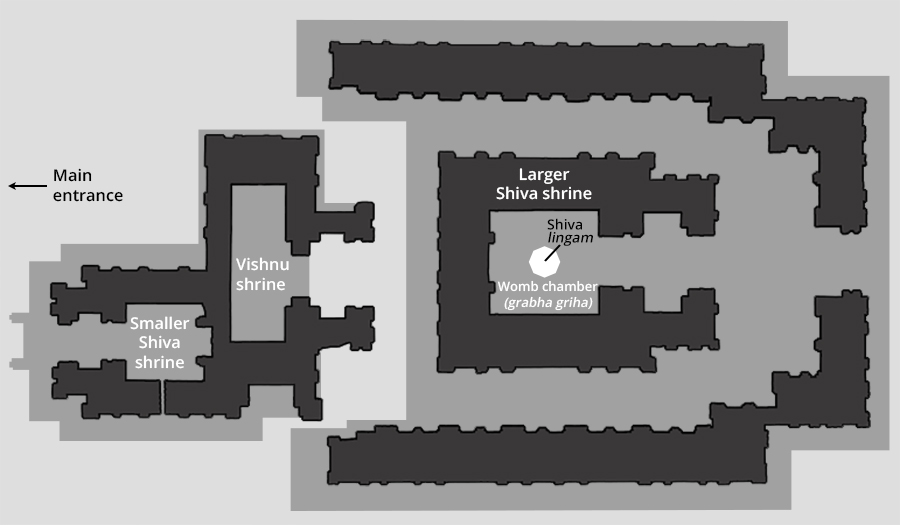

A temple with three shrines

The Shore Temple is both a rock cut and a free-standing structural temple. The entire temple stands on a naturally occurring granite boulder. The complex consists of three separate shrines: two dedicated to the god Shiva, and one to Vishnu. The Vishnu shrine is the oldest and smallest of the three shrines. The other elements of the temple, including the gateways, walls, and superstructures were constructed out of quarried stone and mortar. The entrance to the temple complex is from the western gateway, facing the smaller Shiva shrine. On each side of the gateway stand door guardians known as dvarapalas who welcome visitors to the complex and mark the site as sacred. The smaller Vishnu temple sits between the two Shiva shrines, connecting the two. It has a rectangular plan with a flat roof and houses a carved image of the god Vishnu sleeping. Images of Vishnu reclining or sleeping on the cosmic serpent Shesha-Ananta, appear throughout Indian art. While the artists who made this carving did not include a depiction of Shesha-Ananta, it is possible that originally the rock was painted to include the snake. The shrine walls have carvings depicting the life stories of Vishnu and one of his avatars, Krishna.

Like the Vishnu shrine, the two Shiva shrines include rich sculptural depictions on both their inner and outer walls. The large Shiva shrine faces east, and has a square plan with a sanctum and a small pillared porch known as a mandapa. At the center of the shrine is a lingam, the aniconic form of Shiva in the shape of a phallus. Though the temple is not a site of active worship today, visitors can sometimes be seen worshipping and offering flowers to the lingam, bringing the sacred site back to life.

On the back wall of the shrine appear carvings of Shiva (this time in anthropomorphic or human-like form) with his consort, the goddess Parvati, and their son Skanda. The inner walls of the mandapa contain images of the gods Brahma and Vishnu, and the outer north wall of the sanctum includes more sculptures of Shiva as well as a depiction of the goddess Durga. The small Shiva shrine faces west and has a square plan with a sanctum and two mandapas. As with the larger Shiva shrine, the smaller shrine’s sanctum originally housed a lingam, which is now missing. A sculpted panel depicting Shiva, Parvati, and Skanda enlivens the back wall. Both Shiva shrines have identical multi-storied pyramidal superstructures typical of the Dravidian style.

The rich sculptural program seen throughout the three shrines continues on the outer walls of the Shore Temple, facing the sea. Years of wind and water have worn away the details of these carvings, much in the same way that the sea erodes and shapes boulders over centuries. A row of seated bulls appear at the entrance wall (prakara) of the larger Shiva shrine. These bulls represent Nandi, the vahana or vehicle of the god Shiva. Nandi is believed to be the guardian of Shiva’s home in the Himalayas, Mount Kailasha, and a seated Nandi sculpture is an essential part of a Shiva temple.

A majestic sight

As an architectural form, the Shore Temple is of immense importance, situated on the culmination of two architectural phases of Pallava architecture: it demonstrates progression from rock cut structures to free standing structural temples, and displays all the elements of mature Dravidian architecture. It signifies religious harmony with sacred spaces dedicated to both Shiva and Vishnu, and was also an important symbol of Pallava political and economic strength.

According to legend, sailors and merchants at sea could spot the shikharas of the temple from a distance and use those majestic towers to mark their arrival to the prosperous port city of Mahabalipuram. In this way, not only was the temple a home for the gods Shiva and Vishnu, but also a feature of the landscape, and an icon of the dominion of the great Pallava kings.

Copyright: Dr. Anisha Saxena, “Shore Temple, Mamallapuram,” in Smarthistory, April 24, 2019, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/shore-temple-mamallapuram/.

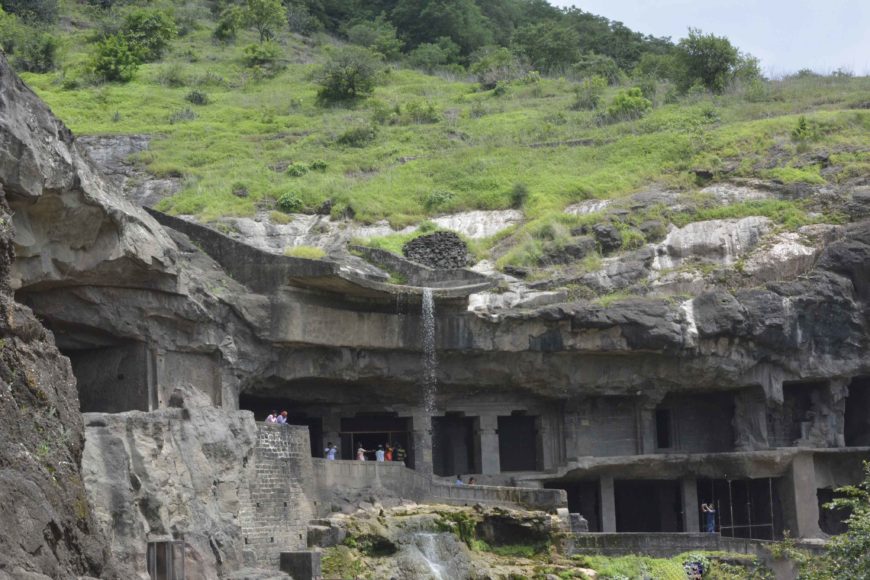

Ellora Caves

The caves at Ellora in Maharashtra, India, are among the most impressive examples of rock-cut architecture found on the subcontinent. The Archaeological Survey of India has identified thirty-four caves at Ellora carved into an exposure of basalt that stretches over a mile in length.

The caves date from the late sixth through tenth centuries—an important period of temple building in India as regional rulers, merchants and traders, and religious communities sought to establish their presence and power through the patronage of structural and rock-cut architecture.

At Ellora, there are caves affiliated with three of India’s religious traditions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. As in other multireligious sites that feature caves—such as Aihole and Badami in Karnataka—it is the rocky topography that likely attracted initial excavation activities. Caves were, and continue to be, associated with specific sacred mountains that are central to ancient Indian cosmologies. Thus, caves not only offered quite suitable conditions for ascetic living on a practical level, but also created a sacred environment for both occupants and visitors.

Scholarship on Ellora tends to present the site’s internal development as follows:

- early Hindu activity (c. late 6th through early 7th century C.E.)

- Buddhist phase (c. 7th through the first quarter of the 8th century C.E.)

- renewed Hindu activity (c. mid-8th through early 9th century C.E.)

- Jain phase (c. 9th through 10th century C.E.).

However, recent research reveals that the site developed more organically with artists working on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain caves simultaneously at certain times. [1] Artists did not work on caves according to their own personal religious affiliation nor did they work as specialists for only one type of cave. Close examinations of architectural elements and their ornamentation—as well as treatments of sculptural form and iconographical features—indicate that artists moved back and forth across the site. Importantly, artists established sacred visual vocabularies that crossed religious boundaries.

Early caves devoted to Shiva

The earliest caves (14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, 28 and 29) are located near the center of the site. [2] Almost all are dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva and house a rock-cut linga (an abstract, columnar form of Shiva).

Cave 29, the largest early cave

The largest of the early spaces is Cave 29 and it is carved next to a waterfall created by the force of Ellora’s Velganga river during the monsoon season. As seen in other expansive rock-cut sites across the subcontinent (such as the caves of Ajanta), early caves tend to be clustered close to a primary water source.

The linga shrine in Cave 29 is carved as a separate architectural unit that can be circumambulated within the cave. The presentation of a free-standing linga-shrine distinguishes Ellora’s early Shaiva caves from those that are carved in the eighth and ninth centuries (Caves 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, and 24). In the later Shaiva caves, the linga shrine is carved directly from the back wall of the cave.

In addition to the linga shrine, Cave 29 features numerous sculpted panels of Shiva and other deities in figural form. Subjects include, for example, Shiva destroying demons, Shiva as lord of yogis, the marriage of Shiva and Parvati, and Shiva dancing. Similar to the sculpted programs in Cave 1 at Elephanta, the panels appear to present Shiva through complementary acts of creation, destruction, earthly and cosmic engagements, and ascetic practices. These two colossal reliefs at Ellora are carved facing each other at the western entrance to Cave 29. The relief of Shiva destroying Andhaka presents the god with multiple arms so that he can hold a variety of weapons and other items. His dynamic lunge and ferocious facial expression emphasize the arduous task in slaying this demon. In the Shiva subduing Ravana panel, the god simply places his foot down upon the ground to quell the shaking of Mt. Kailasa caused by Ravana below. Both sculpted reliefs prominently include Shiva’s female consort Parvati.

Cave 29. Use the arrows to enter the cave.

While the subjects of these panels can be identified quite easily, interestingly, many of the carvings in Cave 29 remain “unfinished” in one way or another. One of the most incredible aspects of rock-cut architecture is the fact that artists could create colossal sculpted programs without worrying about the structural integrity of the cave. Furthermore, the subdued lighting within these spaces surely contributed to perceptions of sculpted form materializing (or self-manifesting) from temple walls. Adding to this visual experience is the fact that most of Ellora’s carved architectural and sculptural elements were once painted (or were intended to be painted) with natural pigments. Recent examinations of these reliefs by art historian Vidya Dehejia and sculptor Peter Rockwell prompt us to consider processes of sculpting as well as premodern conceptions of “completeness.” [3] For example, in the Shiva destroying Andhaka panel, portions of the rock beneath Parvati have been left unfinished. These areas only reveal the marks of the point chisel—a preliminary tool in sculpting. Though “incomplete”, the unfinished areas in this relief in no way detract from its readability and suggest that artists and viewers in premodern India had more fluid notions of a sculpture’s state of completion.

Buddhist caves (Caves 1–12)

In the early seventh century, artists shifted to available rock at the southern end of the site. Here, while working on Cave 14—a temple likely created for the worship of the Hindu goddess Durga—artists also began carving Buddhist residences and worship spaces. [4]

There are twelve Buddhist caves at Ellora: eleven serving, in part, as residences (viharas) for monastic communities and one chaitya hall containing a rock-cut stupa carved with a figural, seated Buddha. The singular chaitya hall at Ellora is apsidal in plan and is carved with a ribbed barrel-vaulted ceiling. Rock-cut pillars forming side aisles create a path for circumambulation around the stupa. In addition, devotees can approach on axis from the central aisle of the hall to engage directly with the Buddha image.

The site’s earliest viharas (Caves 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) present a relatively standard plan encountered in the late fifth-century caves at Ajanta and in select caves at nearby Aurangabad. This includes a quadrangular, pillared hall with individual monastic cells, and a shrine containing a large rock-cut Buddha image, such as we see in Cave 3. Other sculptural programs in Ellora’s Buddhist caves include reliefs of female deities, bodhisattvas, series of Buddhas, and mandalas (sacred diagrams).

Cave 12: architecture as sacred diagram

In her important study of Ellora’s Buddhist caves, Geri Malandra identifies the mandala as a governing framework for understanding the sculptural programs and their arrangement within the caves. [5] Mandalas are schematic arrangements of Buddhas, Buddhist deities, and bodhisattvas. They can serve as maps or diagrams during meditation and worship to reveal complex spatial connections between earthly and cosmic realms. Ellora’s Buddhist caves feature mandalas carved in relief and as part of an expansive, three-dimensional shrine program.

Numerous reliefs of mandalas are carved in the three-storied vihara, Cave 12. In this relief, we see nine figures, each placed into its own rectangular space. The central figure is a Buddha who is surrounded by eight ornamented bodhisattvas. Mandalas like this one may have served as a guide for worship as it would have been viewed prior to entering into the main shrine. Significantly, this mandala replicates the large-scale shrine programs of all three stories of Cave 12 which include a seated Buddha flanked by groups of bodhisattvas.

Walk through Cave 12 to see numerous examples of sculpture in a cave

Although mandalas are popularly known through painted examples across Buddhist Asia, Ellora’s Buddhist caves can also be viewed as three-dimensional representations. This is underscored by the carving of such diagrams in liminal spaces of the cave, such as in or near shrine rooms, at stairwells, and on ground level (such as the example from Cave 12). Our movement through the Buddhist caves—inward towards shrines and upward towards top levels—parallels visualization practices aided by mandalas. Some of these practices likely included visualizing the different realms governed over by specific bodhisattvas that ultimately lead to enlightenment and Buddhahood.

Questions of patronage at Ellora

Scholars generally identify the patrons of Ellora’s early Hindu and Buddhist caves as rulers of the Kalachuri and Chalukya courts, respectively, even though there is no inscriptional evidence at the site to confirm such associations. Royal use of the site is, however, recorded in three inscriptions affiliated with a dynasty of rulers known as the Rashtrakutas. In 742 C.E., the Rashtrakuta king Dantidurga visited the site and purified himself by bathing at the tirtha (sacred pilgrimage place) of the “Lord of the Cave” (a phrase from Dantidurga’s copper-plate land grants, found at Ellora, that refers to the god Shiva). [6] This ritual ablution may have taken place in the body of water formed by the waterfall adjacent to Cave 29. This would make sense because Cave 29 likely continued to serve as an important Shiva temple at Ellora.

The importance of Ellora for Dantidurga is also witnessed in an inscription carved on a monolithic pavilion that precedes Cave 15. Throughout Ellora’s caves, this is the only inscription carved on a monument to link it with a royal dynasty. The inscription, located above the central, pierced-stone window, begins with an invocation to Shiva and documents the genealogy of the Rashtrakutas. The list of kings ends with praise for Dantidurga’s accomplishments, including his victory over other regional kings. [7]

While the Cave 15 inscription ties Dantidurga (and the Rashtrakutas) to Ellora, curiously, it does not identify him as the patron of the monolithic pavilion or the multistoried cave behind it. Moreover, the visual evidence of Cave 15 indicates that this monument was initially carved out prior to Rashtrakuta involvement with the site. Images of seated Buddhas are carved on the bracket-capitals of the upper-story veranda pillars, indicating that Cave 15 began as a multistoried Buddhist cave, much like Caves 11 and 12. However, perhaps in response to Dantidurga’s visit, large Shaiva guardians were subsequently carved into the façade (and interior programs were added) to transform the cave into an abode of Shiva. This transformation ushered in a dynamic period of excavation activity at Ellora by a multitude of patrons in the eighth through tenth centuries. Monuments include additional temples to Shiva (such as the Kailasanatha) and a Jain complex of caves.

Kailasanatha—a temple beyond the cave

The site’s most impressive monument is actually not a cave per se, but a rock-cut monolithic temple. This temple is Cave 16, also known as the Kailasanatha. The name of this temple makes reference to Shiva’s residence on Mt. Kailasa—a sacred mountain and axis mundi in select Indian cosmologies. To create the temple, stone-cutters had to first carve three trenches into the hill to isolate a rectangular block of stone. While teams of artists tackled the back of the block to begin the top of the temple’s main tower, others focused on shaping the colossal gateway and other components of the temple. Remarkably, though the Kailasanatha is cut from the living rock, it replicates elements found in structural (not rock-cut) temples, including the gateway, a separate pavilion for Shiva’s bull Nandi, a pillared main hall, subsidiary shrines around the main tower, and a sanctum enshrining a rock-cut linga. The extraordinary nature of the Kailasanatha as a simulacrum of a structural temple is only surpassed by the high quality of its imagery. The temple tower and the exterior walls of the main hall are carved with a variety of proliferating forms including vegetal and aquatic motifs, vessels of abundance, flying celestial figures, and the entire pantheon of Hindu deities. A number of the colossal reliefs carved on the exterior of the temple make direct reference to Shiva’s Himalayan abode on Mt. Kailasa—further linking this monument to Shiva’s place of residence.

Inside the Kailasanatha

Carved entirely from the rock, the Kailasanatha is perhaps the most dramatic expression of the temple as sacred mountain and cave. The spectacular form and innovation of this sculpted temple is highlighted in a famous inscription issued by a ruling king of the dynasty’s branch in Gujarat. The reference to the Kailasanatha temple is found in the genealogical account of the dynasty and states that Dantidurga’s successor, Krishnaraja I constructed a temple so wondrous that it astonished the gods and even the architect who made it. [8] Although most scholars cite this inscription as evidence of Krishnaraja’s patronage of Ellora’s Kailasanatha temple, this particular record is somewhat problematic given its late date (forty years after his reign), place of issue (western state of Gujarat), and the fact that this information is not repeated in other Rashtrakuta genealogies. Thus, the exact nature of Rashtrakuta patronage at Ellora remains unclear. [9]

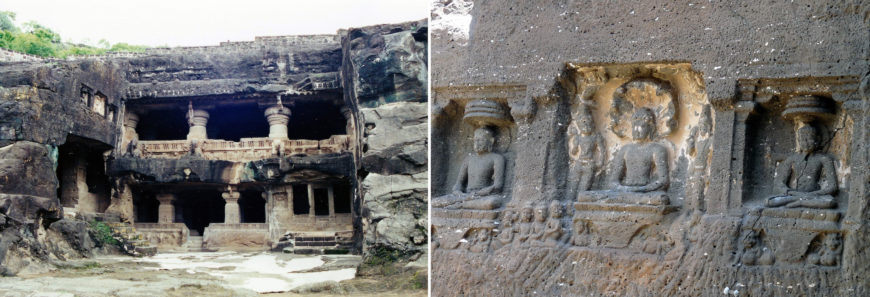

Through a Jain lens

Ellora’s Jain caves provide more information in regard to patronage and the site’s internal development. Five Jain caves (Caves 30–34) are carved at the northern end of the site. The sculpted and painted programs feature Jinas, Jain deities (particularly associated with health, wealth, and abundance), and the Jain figure Bahubali. Reliefs of Bahubali at Ellora typically present the figure flanked by two females who are in the process of removing the vines that encircle his legs. Overhead are flying, celestial couples who hold long flower garlands to honor and worship Bahubali who has just attained omniscience due to his steadfast meditation. The forest setting of this event is referenced through the vines and the small deer that gather around his feet.

In addition to these subjects, the Jain caves are also carved with numerous human worshippers, both monastic and lay. [10] Typically they are carved in gestures of homage at the feet of a Jina. Some of these figures are identified through an inscription as the patron(s) of the sculpture, such as Nagavarma and Sohila in Cave 32. Their presence points to patterns of patronage at the site that go beyond royal elites. Moreover, it appears that scenes of human devotion made an impression on later imagery carved at the site, as seen in some additions to the Kailasanatha complex that feature portraits of anonymous devotees worshipping Shiva.

While the vast majority of Ellora’s Jain caves were carved in the ninth and tenth centuries, there is some evidence that Jain artistic activity was initiated much earlier. This can be seen in the pillar type carved in the upper-story veranda of Cave 33. These pillars, with their fluted, cushion-shaped capitals and tall, plain shafts, mirror those carved in some of the site’s early Shaiva and Buddhist caves. Also supporting an earlier date for the inception of Jain activity are three Jina images carved adjacent to Cave 33. The throne bases supporting these Jinas have a cloth or fabric that drapes down and covers the central section of the base. Carved above the cloth is a double-lotus seat that visually supports the Jina. These motifs are similarly found on the thrones supporting select Buddhas at the site. [11] These elements, among others, indicate a seventh or early eighth-century date for initial Jain activity. This is significant as it demonstrates that teams of artists were working on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain caves simultaneously during this period.

The three Jina images adjacent to Cave 33 likely served as “placeholders” until artists could resume work on the Jain caves after the completion of the monolithic Kailasanatha temple in the mid-eighth century. As a result, we also have the innovative “Chhota (small) Kailasa” at Ellora (Cave 30)—a monolithic Jain temple that replicates the Kailasanatha in terms of its process of creation, directional orientation, and main architectural components, albeit on a smaller scale. [12]

Undoubtedly, future research will reveal more evidence for the movement of artists across the site and highlight ways that Ellora functioned as a multireligious tirtha in India’s early medieval period.

Cave 33, interior

Copyright: Dr. Lisa N. Owen, “The multireligious caves at Ellora,” in Smarthistory, July 29, 2021, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-multireligious-caves-at-ellora/.

PERFORMING ARTS

Music

Classical Indian Music

Indian classical music is based on the concept of ragas, which are melodies that evoke certain emotions in the listener. Some of the most popular ragas used in Indian music include Bhairav, Yaman, Malkauns, Todi, Bhupali, Marwa, and Darbari. Each raga has a distinct melodic structure and is associated with a particular time of day, season, or mood.

Talas are rhythmic cycles used in Indian classical music. They are composed of a specific number of beats and can be used to structure improvisations, compositions and performances. Talas are divided into three parts: thekhādī, the vibhāg and the laggī. Thekhadi is the cyclical pattern of beats, the vibhag divides the cycle into two halves and the laggi is the part of the cycle which is improvised. Each tala has its own unique character, which is determined by the number of beats and the way in which they are grouped together. Talas are an essential part of Indian classical music, and are used to create a sense of structure, repetition and form in the music.

In Indian classical music, a tala is a rhythmic cycle that serves as the foundation for a composition or improvisation. It is characterized by a specific number of beats and a specific time-cycle and is usually indicated by a specific hand or finger gesture called a “kriya” that is used by the percussionist to signal the start of each cycle.

Tala is an integral part of Indian classical music and is used in both Hindustani and Carnatic music traditions. The use of tala creates a structure for the improvisation and composition by providing a framework for the musicians to build their improvisations around.

In Hindustani music, talas are classified into four main categories: Trital, Dhamar, Ek tal, and Jhaptal.

In Carnatic music, talas are classified into three main categories: Tisra, Chatusra, and Misra.

Each tala has its own specific name, such as Dadra, Jhaptal, and Rupak in Hindustani music and Adi, Rupaka, and Triputa in Carnatic music.

The use of talas requires a high level of skill and practice to master, as the musician must be able to keep a steady beat while also improvising and adapting to the other musicians in the ensemble.

Indian classical music is traditionally performed on a variety of instruments, many of which have been in use for centuries. Some of the most used instruments in Indian classical music include:

Sitar: A long-necked string instrument with a large number of strings that is played with a plectrum (mizrab) and is commonly used in Hindustani music.

Sarod: A string instrument with a deep, mellow tone that is played with a plectrum (jawari) and is commonly used in Hindustani music.

Tabla: A pair of small hand drums that are played with the fingers and palms and are used to provide the rhythm in Indian classical music.

Harmonium: A small reed organ that is played with the fingers and is used to provide accompaniment in Indian classical music.

Mridangam: A double-headed drum that is played with the hands and is commonly used in Carnatic music.

Ghatam: A clay pot that is played with the hands and is commonly used in Carnatic music.

Kanjira: A tambourine-like instrument that is played with the hands and is commonly used in Carnatic music.

Violin: A bowed string instrument that is played with a bow and is commonly used in both Hindustani and Carnatic music.

Flute: A wind instrument that is played by blowing into a hole and is commonly used in both Hindustani and Carnatic music.

Sarangi: A bowed string instrument that is played with a bow and is commonly used in Hindustani music.

These are just some of the instruments commonly used in Indian classical music, and there are many more instruments that are used depending on the specific style and tradition of music.

In Indian music, texture refers to the way in which the different musical elements of a piece are arranged and combined. There are several different types of texture found in Indian music, including:

Monophonic: A monophonic texture is one in which a single melody is played or sung. This is often the case in traditional Indian vocal music, where a solo vocalist sings a melody accompanied by a drone or a simple percussion instrument.

Polyphonic: A polyphonic texture is one in which multiple melodies are played or sung simultaneously. This is less common in Indian music, but can be found in some forms of Indian classical music, such as the South Indian carnatic music where there is a use of counterpoint melodies.

Homophonic: A homophonic texture is one in which multiple voices or instruments play or sing the same melody simultaneously, but with slightly different variations. This type of texture is common in Indian classical music, particularly in ensemble performances where multiple instruments play the same melody in a coordinated manner.

Heterophonic: A heterophonic texture is one in which multiple voices or instruments play or sing the same melody simultaneously, but with slightly different variations. This is a common feature in Indian classical music, particularly in improvisation, where the musicians play the same melody with different nuances.

Drone: Drone is a constant and unchanging sound that provides a foundation for the melody to be played or sung. The use of drone is common in Indian classical music, particularly in vocal music where the drone is provided by a tanpura or a sruti box.

Overall, Indian music is known for its rich and diverse textures, which are created through the combination of different musical elements such as melody, rhythm, and timbre.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Zlshv4TqIHw?si=AIxUm1G1SfYa559O

Copyright: Chapter 3: The Music of India Copyright © 2023 by Antoni Pizà is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Theater

Video URL: https://youtu.be/5lp-HBv-3bA?si=ZAnaRUXoXLT_gMT9

VISUAL ARTS

Portraying Hindu Gods

Vishnu- the Hindu Preserver

Vishnu is one of the most popular gods of the Hindu pantheon. His portrayal here is standard: a royal figure standing tall, crowned and bejeweled, in keeping with his role as king and preserver of order within the universe. He carries a gada (mace) and chakra (disc) in his hands. The other two hands, which would have held a lotus and conch, are broken. On his forehead he wears a vertical mark or tilak, commonly worn by followers of Vishnu. In keeping with his iconography as the divine king, he is heavily bejeweled, wears a sacred thread that runs over his left shoulder and a long garland that comes down to his knees.

He stands flanked by two attendants, who may be his consorts Bhu and Shri, on a double lotus. The stele has a triangular top unlike earlier examples which were usually in the shape of a gently lobed arch. On either side of his crown are celestial garland bearers and musicians, the Vidyadharas and Kinnaras. A kirtimukha, or auspicious face of glory, is carved on the top centre of the arch.

The sculpture is typical of workmanship of the Pala dynasty of twelfth-century Bengal. The heart-shaped face with stylized arched eyebrows, long eyes that are slightly upturned at the ends, the broad nose, and the pursed smile are all characteristic.

Shiva- the Lord of the Dance

Shiva is a powerful Hindu deity, sometimes called the destroyer. “Destroyer” in this sense is not an entirely negative force, but one that is expansive in its impact. In Hindu religious philosophy all things must come to a natural end so they can begin anew, and Shiva is the agent that brings about this end so that a new cycle can begin. He has a female consort, like most of the gods, one of whose names is Parvati, “the daughter of the mountain.” Shiva and Parvati may appear as a loving couple sitting together in a form called Umamaheshvara. In this example two separate bronze images have been designed as a group. Both Shiva and Parvati wear elaborate jewelry. Shiva is the more powerful deity and so he is depicted with four arms and is the taller figure. In his hands he holds his weapon, the trident, a small deer and a fruit. His fourth hand is raised in reassurance (abhayamudra). Like other images of Shiva he wears two different earrings. Parvati holds a lotus in one hand and a round fruit in the other.

Bronze-casting in the eleventh century was highly developed in Tamil Nadu in the far south of India. However, these two bronzes are unusually large for the Deccan in the same period.

The erect frontal pose of these two figures contrasts with the relaxed, naturalistic posture of many images from Tamil Nadu of the Chola period.

During this period a new kind of sculpture is made, one that combines the expressive qualities of stone temple carvings with the rich iconography possible in bronze casting. This image of Shiva is taken from the ancient Indian manual of visual depiction, the Shilpa Shastras (The Science or Rules of Sculpture), which contained a precise set of measurements and shapes for the limbs and proportions of the divine figure. Arms were to be long like stalks of bamboo, faces round like the moon, and eyes shaped like almonds or the leaves of a lotus. The Shastras were a primer on the ideals of beauty and physical perfection within ancient Hindu ideology.

A dance within the cosmic circle of fire

Here, Shiva embodies those perfect physical qualities as he is frozen in the moment of his dance within the cosmic circle of fire that is the simultaneous and continuous creation and destruction of the universe. The ring of fire that surrounds the figure is the encapsulated cosmos of mass, time, and space, whose endless cycle of annihilation and regeneration moves in tune to the beat of Shiva’s drum and the rhythm of his steps.

In his upper right hand he holds the damaru , the drum whose beats syncopate the act of creation and the passage of time. His lower right hand with his palm raised and facing the viewer is lifted in the gesture of the abhaya mudra , which says to the supplicant, “Be not afraid, for those who follow the path of righteousness will have my blessing.” Shiva’s lower left hand stretches diagonally across his chest with his palm facing down towards his raised left foot, which signifies spiritual grace and fulfillment through meditation and mastery over one’s baser appetites. In his upper left hand he holds the agni (image left), the flame of destruction that annihilates all that the sound of the damaru has drummed into existence.

Shiva’s hair, the long hair of the yogi, streams out across the space within the halo of fire that constitutes the universe. Throughout this entire process of chaos and renewal, the face of the god remains tranquil, transfixed in what the historian of South Asian art Heinrich Zimmer calls, “the mask of god’s eternal essence.”

Brahma- the Hindu Creator God

It is often said that there is a trinity of Hindu gods: Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer. But while Vishnu and Shiva have followers and temples all over India, Brahma is not worshiped as a major deity. Brahma is the personified form of an indefinable and unknowable divine principle called by Hindus brahman. In the myth of Shiva as Lingodbhava, when Brahma searches for the top of the linga of fire, Brahma falsely claimed that he had found flowers on its summit, when in fact the Shiva linga was without end. For this lie he was punished by having no devotees. There are very few temples dedicated to Brahma alone in India. The only one of renown is at Pushkar, in Rajasthan.

Brahma can be recognized by his four heads, only three of which are visible in this sculpture. In two of his four hands he holds a water pot and a rosary. Brahma originally had five heads but Shiva, in a fit of rage, cut one off. Shiva as Bhairava is depicted as a wandering ascetic with Brahma’s fifth head stuck to his hand as a reminder of his crime. Brahma is commonly placed in a niche on the north side of Shaiva temples in Tamil Nadu together with sculptures of Dakshinamurti and Lingodbhava.

The British Museum, “Three Hindu gods,” in Smarthistory, March 30, 2020, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/three-hindu-gods/.

Farisa Khalid, “Shiva as Lord of the Dance (Nataraja),” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/shiva-as-lord-of-the-dance-nataraja/.

Parvati

Video URL: https://youtu.be/1Qm7jJ2lP60?si=9S_3ebPGVcKhVejL

Durga Slay the Buffalo Demon

The story of Mahishasuramardini (in Sanskrit: “crusher of Mahishasura”) is preserved in a devotional text from c. 600 C.E. titled the Devi Mahatmya (“Glory of the Goddess”) which exalts the divine feminine force shakti, also known as Mahadevi.

This episode, which recounts the deeds of the goddess Chandika (later known as Durga), a fierce warrior, is carved in an exquisite bas-relief panel inside a rock-cut cave temple known as Mahishasuramardini mandapa (hall) in the town of Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu, India.

The goddess is roughly life-sized and draws her bow as she steadies an implied arrow. [4] The weapons in her six other arms have been identified, in clockwise order:

- a sword

- a bell

- a wheel (or discus)

- a noose to restrain her enemies

- a conch shell

- a shield [5]

She is shown wearing a dhoti (cloth tied at the waist) — notice the hem just above the knee that delineates the garment — and a kuca bandha (breast band). Like the kuca bandha, the dhoti may have once carried patterned details, but this is no longer visible. Durga is also adorned with a distinct crown and jewelry including large earrings, necklaces, bangles, armlets, belt, and anklets, all of which demonstrate her divinity and royalty. Even the goddess’s vahana (vehicle), a lion, is beautifully ornamented with a mane of neatly demarcated ringlets.

Duga is surrounded by an entourage of several gana (small, male attendants) and a singularly remarkable female warrior at the bottom center who is raising her sword (see detail below). In addition to gana who support the goddess in battle, see for instance the moustached gana who stands beneath her foot and takes aim at the villains, again, with an implied arrow, and the others that appear at the ready with sword and shield, there are gana who underscore the goddess’s identity as both divine and royal. Two gana carry attributes signifying royalty (i.e., a parasol and a fly-whisk) above the goddess and another (at the top-left) flies into the scene holding a plate with offerings for Durga.

-

The Great Goddess Durga (Mahishasuramardini) Slaying the Buffalo Demon, Kota (Rajasthan, India), watercolor and metallic paint on paper, c. 1750, image 9 7/8 × 11 inches; sheet: 10 11/16 × 12 3/8 inches (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Stella Kramrisch Collection 1994)

Copyright: Dr. Arathi Menon, “Durga Slays the Buffalo Demon at Mamallapuram,” in Smarthistory, July 31, 2019, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/durga-mahisha-mamallapuram/.