27 CENTRAL ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

Sultanate art and architecture in India

Mosques, tombstones, textiles, and murals are only a few examples of the art and architecture created on the Indian subcontinent in the sultanates. The sultanates were areas governed by Muslim sultans that were originally unified as the Delhi sultanate but would eventually fracture into independent states, and whose art and architecture was innovative and eclectic, drawing on sources from across Asia. For some sultanates, the Indian Ocean trade network, which connected East Africa, the Arabian peninsula, the south coast of Iran, the Indian subcontinent, and south east Asia, allowed for the easy mobility of objects and ideas across this vast geography. For others, overland trade and shifting political affiliations would facilitate mobility. By the fourteenth century, the Delhi sultanate had expanded considerably, extending all the way south to encompass the Deccan Plateau. Their hold over this vast empire, however, was often tenuous and multiple groups—in Gujarat, northern Karnataka, Jaunpur, Bengal, and Sindh—broke away to form independent sultanates.

Map of the sultanates (Gujarat, Sindh, Jaunpur, Bengal, and the Bahmani, sultanate), c. 1400; also indicated are the cities of Delhi and Bidar (underlying map © Google)

The arts of these breakaway states were influenced by the artistic traditions of the Delhi sultans. One of the earliest and most influential examples of architecture from the Delhi sultanate is the Qutb complex in Delhi. Key elements of the complex, notably the architectural stone screen in front of the prayer hall and the towering Qutb minar (tower), would be replicated or referenced in monuments across the Subcontinent. Sultanate arts did not simply replicate the architecture of Delhi, however, they were also informed by local styles, materials, and practices resulting in an astonishing variety of artistic products.

The courtyard of the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi. In the foreground are pillars of the colonnaded walkway and in the background is the 12th-century screen and prayer hall. (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Dr. Fatima Quraishi, “Sultanate art and architecture, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, May 20, 2022, accessed May 2, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/sultanate-art-architecture-introduction/.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Talismanic Textiles

Video URL: https://youtu.be/CaxKhMwYvK4?si=_FKEP3DiTNbGykyp

LITERATURE

ARCHITECTURE

Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho (India)

The temples at Khajuraho, including the Lakshmana temple, have become famous for these amorous images—variations of which graphically depict figures engaged in sexual intercourse. These erotic images were not intended to be titillating or provocative, but instead served ritual and symbolic function significant to the builders, patrons, and devotees of these captivating structures.

Sculpture of a woman removing a thorn from her foot, northwest side exterior wall, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 C.E. (image source)

Look closely at the image to the above. Imagine an elegant woman walks barefoot along a path accompanied by her attendant. She steps on a thorn and turns—adeptly bending her left leg, twisting her body, and arching her back—to point out the thorn and ask her attendant’s help in removing it. As she turns the viewer sees her face: it is round like the full moon with a slender nose, plump lips, arched eyebrows, and eyes shaped like lotus petals. While her right hand points to the thorn in her foot, her left hand raises in a gesture of reassurance.

Images of beautiful women like this one from the northwest exterior wall of the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho in India have captivated viewers for centuries. Depicting idealized female beauty was important for temple architecture and considered auspicious, even protective. Texts written for temple builders describe different “types” of women to include within a temple’s sculptural program, and emphasize their roles as symbols of fertility, growth, and prosperity. Additionally, images of loving couples known as mithuna (literally “the state of being a couple”) appear on the Lakshmana temple as symbols of divine union and moksha, the final release from samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth).

Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 C.E. (Chandella period), sandstone (photo: Christopher Voitus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The central deity at the Lakshmana temple is an image of Vishnu in his three-headed form known as Vaikuntha[4] who sits inside the temple’s inner womb chamber also known as garba griha (above)—an architectural feature at the heart of all Hindu temples regardless of size or location. The womb chamber is the symbolic and physical core of the temple’s shrine. It is dark, windowless, and designed for intimate, individualized worship of the divine—quite different from large congregational worshipping spaces that characterize many Christian churches and Muslim mosques.

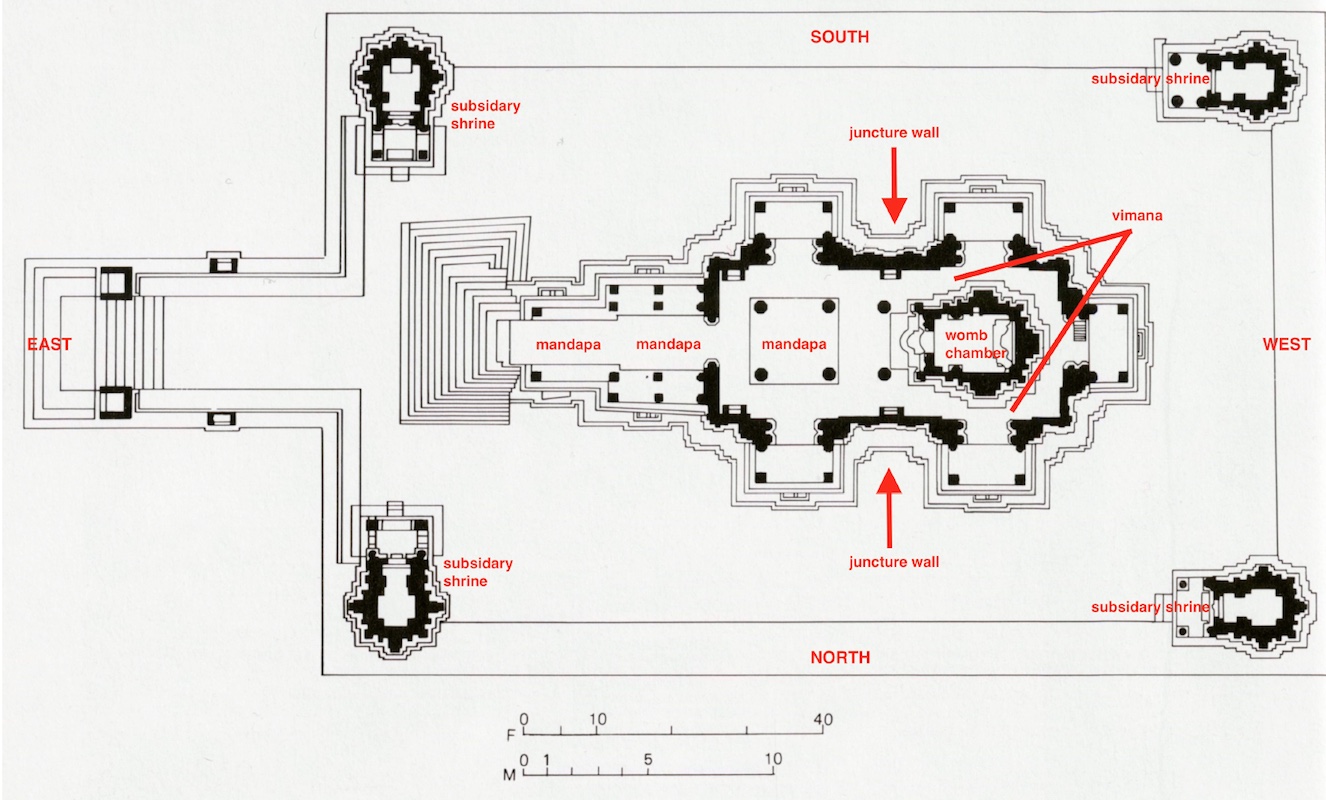

Plan of Lakshmana temple

Devotees approach the Lakshamana temple from the east and walk around its entirety—an activity known as circumambulation. They begin walking along the large plinth of the temple’s base, moving in a clockwise direction starting from the left of the stairs. Sculpted friezes along the plinth depict images of daily life, love, and war and many recall historical events of the Chandella period (see image below and Google Street View).

Devotees then climb the stairs of the plinth, and encounter another set of images, including deities sculpted within niches on the exterior wall of the temple (view in Google Street View).

In one niche (left) the elephant-headed Ganesha appears. His presence suggests that devotees are moving in the correct direction for circumambulation, as Ganesha is a god typically worshipped at the start of things.

Ganesha in niche, exterior mandapa wall, south side, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Manuel Menal, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Other sculpted forms appear nearby in lively, active postures: swaying hips, bent arms, and tilted heads which create a dramatic “triple-bend” contrapposto pose, all carved in deep relief emphasizing their three-dimensionality. It is here —specifically on the exterior juncture wall between the vimana and the mandapa (see diagram above)—where devotees encounter erotic images of couples embraced in sexual union (see image below and here on Google Street View). This place of architectural juncture serves a symbolic function as the joining of the vimana and mandapa, accentuated by the depiction of “joined” couples.

Four smaller, subsidiary shrines sit at each corner of the plinth. These shrines appear like miniature temples with their own vimanas, sikharas, mandapas, and womb chambers with images of deities, originally other forms or avatars of Vishnu.

Following circumambulation of the exterior of the temple, devotees encounter three mandapas, which prepare them for entering the vimana. Each mandapa has a pyramidal-shaped roof that increases in size as devotees move from east to west.

Figural groupings on the temple exterior including Shiva, Mithuna, and erotic couples, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Antoine Taveneaux, CC BY-SA 3.0). View this on Goole Street View.

Once devotees pass through the third and final mandapa they find an enclosed passage along the wall of the shrine, allowing them to circumambulate this sacred structure in a clockwise direction. The act of circumambulation, of moving around the various components of the temple, allow devotees to physically experience this sacred space and with it the body of the divine.

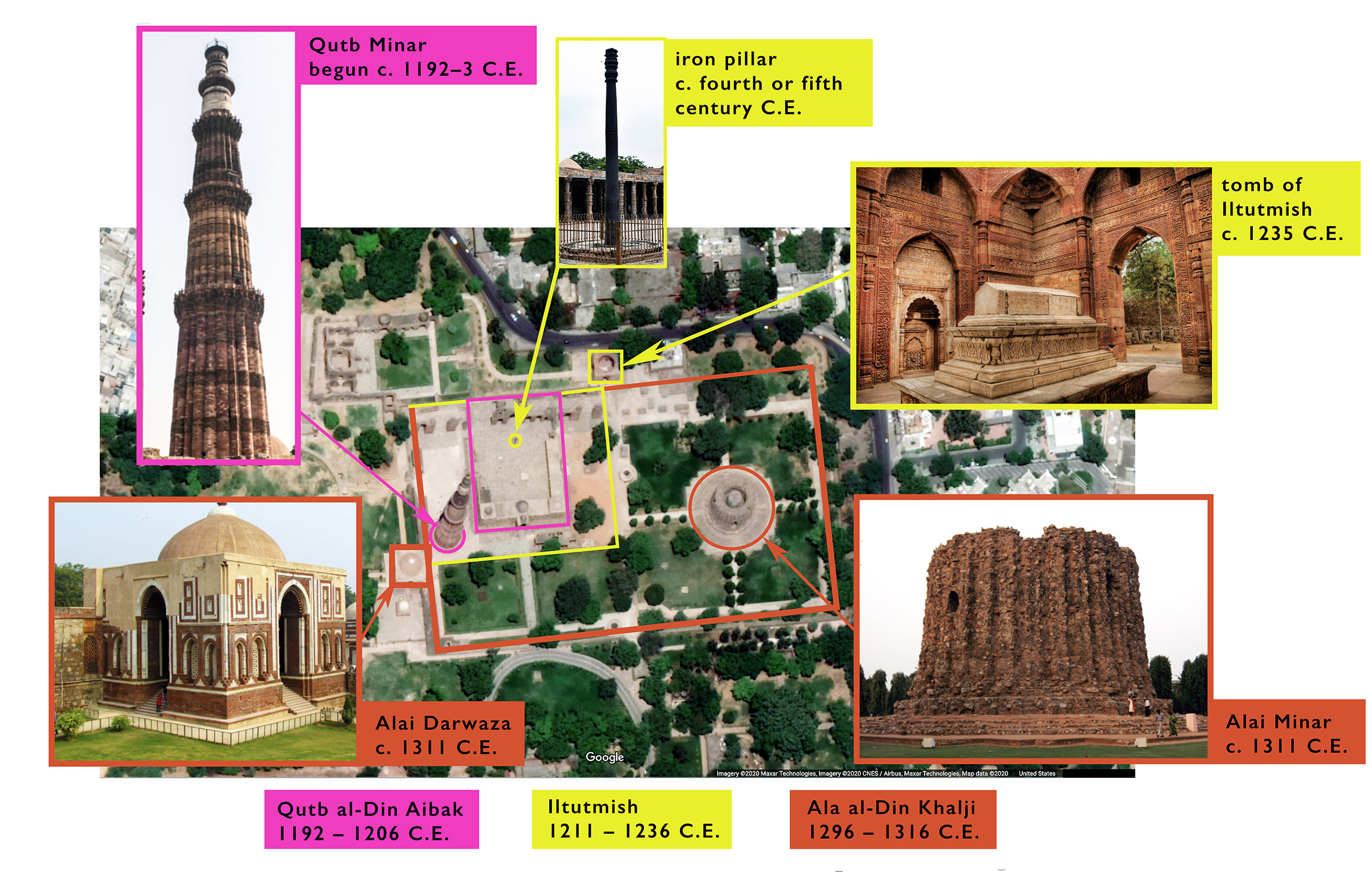

Qutb Complex

The courtyard of the Qutb mosque, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0). In the foreground are pillars of the colonnaded walkway and in the background is a c. 4th – 5th century iron pillar and the mosque’s arched screen and prayer hall.

Layers of cultural, religious, and political history converge in the Qutb archaeological complex in Mehrauli, in Delhi, India. In its beautiful gateways, tombs, lofty screens, and pillared colonnades is a record of a centuries-long history of artistic vision, building techniques, and patronage. At the heart of the Qutb complex is a twelfth century mosque— an early example in the rich history of Indo-Islamic art and architecture.

Plan of the Qutb complex showing the phases of construction of select monuments (photos: clockwise from top, Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0; Bikashrd, CC BY-SA 4.0; Kavaiyan, CC BY-SA 2.0; Alimallick, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Qutb mosque and architectural re-use

The main entrance into the mosque today is on its east side. This arched doorway leads to a pillared colonnade and an open-air courtyard that is enclosed on three sides. Directly across from the main entrance, at the far end of the mosque, is an iron pillar, a monumental stone screen, and a hypostyle prayer hall.

Pillars, ceilings and stones from multiple older Hindu and Jain temples were reused in the construction of the colonnades surrounding the mosque’s open courtyard and in the prayer hall. Since the desired height for the colonnade did not match the height of older temple pillars, two or three pillars were stacked, one on top of the other, to reach the required elevation.

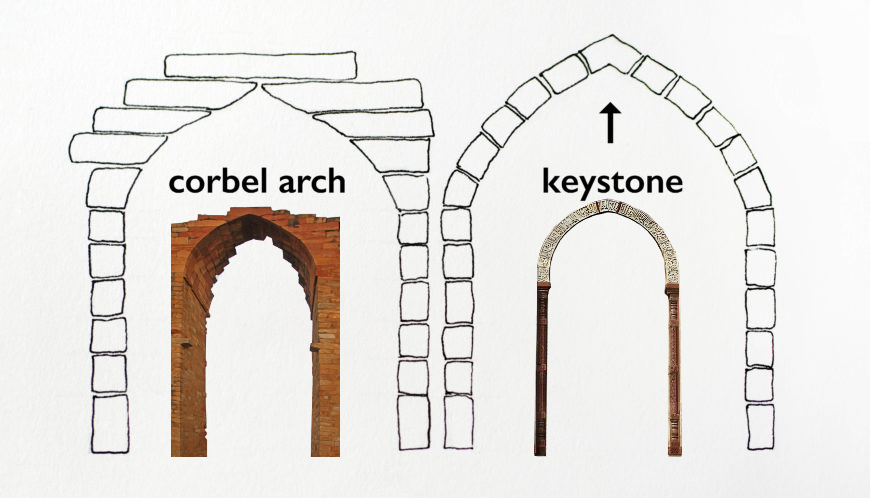

A corbeled arch on the left (inset: Qutb mosque screen, dated 1198) and arch with a keystone on the right (inset: entrance to the Alai Darwaza, dated 1311). Photos: Gerd Eichmann, CC BY-SA 4.0; Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0).

A view of a temple ceiling (constructed in the post and lintel and corbel technique) and pillars in the colonnaded walkway of the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Divya Gupta, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Indian temple pillars are often adorned with anthropomorphic figures of deities and divine beings, mythical zoomorphic, and apotropaic motifs, as well as decorative bands of flowers. A belief by the builders of this mosque in a proscription against the portrayal of living beings is evident in the removal of the faces carved in the older stonework. Other decorative motifs were left untouched, likely for their apotropaic and ornamental qualities.

A view of a temple ceiling (constructed in the post and lintel and corbel technique) and pillars in the colonnaded walkway of the Qutb mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Divya Gupta, CC BY-SA 3.0).

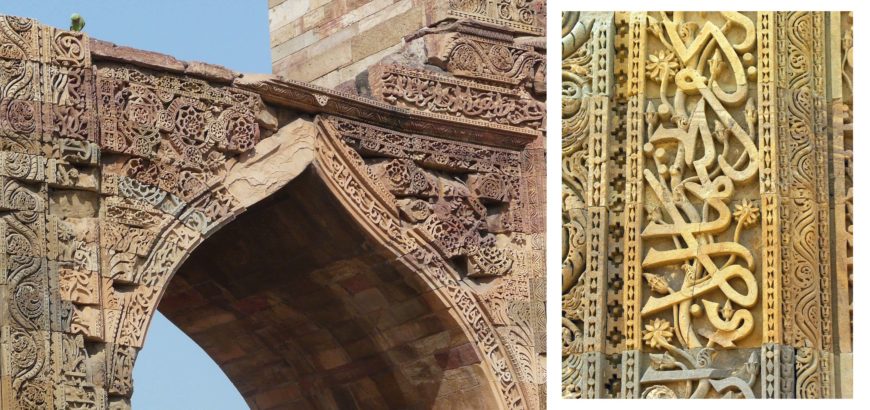

In 1198 Aibak commissioned a monumental sandstone screen with five pointed arches that was built between the courtyard and the prayer hall. The screen was constructed with corbeled arches and is emphatically decorative with bands of calligraphy, arabesques, and other motifs, including flowers and stems that pop over, under, and through the stylized letters (see below).

An arch in the screen (left) and a detail showing the calligraphy on the screen (right), Qutb mosque, screen begun c. 1198, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photos: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0; Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In 1206, following the death of Muhammad Ghuri, Aibak declared himself ruler of the independent Mamluk (translated as “slave”) dynasty. Aibak’s efforts in building the Qutb mosque would endure longer than his tenure as sultan. Later rulers retained the mosque during expansions, indicating their reverence for the first mosque built in Delhi, and their regard for Aibak himself.

When Iltutmish became the new sultan of the Mamluk dynasty in 1211, he made Delhi the capital of the sultanate. During his reign, Iltutmish extended the screen and prayer hall on both sides of the west end of the Qutb mosque and added surrounding colonnades that, in effect, enclosed the original mosque. Iltutmish is also believed to have been responsible for the installation of the iron pillar in the mosque, a dhwaja stambha (ceremonial pillar) that dates to the fourth or fifth century and was originally installed in a Hindu temple.

The pillar has an inscription in the Sanskrit language that praises and eulogizes a ruler. In installing the pillar in the mosque and giving it pride of place, Iltutmish was following a tradition of previous rulers who appropriated such emblems of historic kingship to announce their legitimacy. In appropriating the pillar—and in effect th

Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192–3, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: lensnmatter, CC BY-2.0)

The Qutb Minar

In 1192–93, soon after conquering Delhi, Aibak also began work on the Qutb Minar, the impressive 238 foot tall minaret (tower) of red and light sandstone for his Ghurid overlord. The minar’s tapering, fluted, and angular bands contribute to the soaring affect of the monument. Its balconies are decorated with muqarna style (three-dimensional honeycomb forms) corbels that allow us to imagine the expansive views of Delhi from each of its five stories. The minar is decorated with bands of calligraphy that are both historic (referencing Muhammad Ghuri) and religious.

Detail of the Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192–3, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: juggadery, CC BY-2.0)

Construction on the minar had only reached the height of its first story at the time of Aibak’s death in 1210. The minar would be completed by Iltutmish and its great height and beauty would became emblematic of the power of the Delhi Sultanate.

Exterior view of Iltutmish’s tomb, c. 1236, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

An open-air tomb

Iltutmish’s tomb, which the namesake commissioned during his reign, is located in the northwest corner of the Qutb complex, outside of the mosque’s courtyard. Constructed from new stone (that is, not spolia), this square tomb is relatively simple in its exterior decorative program, but its interior stuns with its overwhelming ornament. Tall pointed arches frame arched doorways and niches, and calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran, floral ornament, arabesques, and geometric patterns adorn the walls.

Although it has been suggested that the tomb is missing its dome, its absence may have been intentional, allowing light to bathe the marble grave marker. Like the ornament that surrounds the tomb’s interior, this light directs our focus to the center of the monument, below which lies Iltutmish’s burial chamber.

Iltutmish’s tomb, c. 1236, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

Like the Qutb mosque and screen, Iltutmish’s tomb was built in the post and lintel fashion and its arches were corbeled. In contrast, less than a hundred years later, arches in Ala al-Din Khalji’s monuments were constructed with a keystone at its summit.

Domed gateways

Ala al-Din Khalji, a fourteenth century ruler who conducted many campaigns to subjugate rivals and to increase his wealth, had plans to expand the Qutb complex substantially. Although he was largely unsuccessful in realizing these ambitions, a ceremonial gateway attributed to his patronage is one of the site’s most important monuments. It is the only remaining monumental gateway of four that are believed to have been built along the perimeter walls of the complex.

Alai Darwaza, c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Known as the Alai Darwaza, the gateway is a square structure built in 1311. Like Iltutmish’s tomb, the gateway is built from new stone. The tall red base, the alternation of white marble and red sandstone ornament, and the latticed windows lend substantial grandeur to the gateway.

The arches in the Alai Darwaza are in the form of horseshoe arches (literally an arch in the form of a horseshoe); the same form is used to also ornament the squinches, i.e., the transition (at the corners of the structure) from the square base to the octagonal ceiling that helps receive the dome. The dome rests on the arches and squinches, in the fashion commonly found in contemporaneous Islamic architecture outside of India.

Interior of the Alai Darwaza showing part of the dome, horseshoe-arch doorways, and the squinch (in the ceiling corner, above the latticed window), c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

While building techniques changed from the corbeled arches of the Qutb mosque to the keystone-arches of the Alai Darwaza, there were also continuities. The use of Indic style architectural ornament (flowers, lotus buds, and bells), for example, remained an emphatic part of the sculptural vocabulary of Sultanate architecture.

Alai Minar

Ala al-Din also began construction of a minar that would have been considerably taller than the Qutb Minar, had it been completed—the unfinished base rises 80 feet in height. All that was built is the rubble core of the structure; the minar would have eventually been faced with stone, perhaps in a fashion and with adornment similar to that of the Qutb Minar.

Alai Minar, c. 1311, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Kavaiyan, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The early sultans of the Delhi Sultanate employed architecture as a tool to announce, maintain, and advance their identity as rulers. Much like older monuments were appropriated in the construction of the Qutb mosque, subsequent sultans appropriated the Sultanate’s earliest work to advance their claims to legitimacy.

Copyright: Dr. Arathi Menon, “The Qutb complex and early Sultanate architecture,” in Smarthistory, June 5, 2020, accessed May 6, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/qutb-delhi-sultanate/.

PERFORMING ARTS

VISUAL ARTS

Textiles in India

South Asia is home to hundreds of textile traditions that have evolved over centuries. Its regionally-varying resources, methods of production, and decoration techniques have given rise to diverse practices of creating cloth with different textures, colors, designs, and functions. Some of these are luxurious and ornamental, crafted for special occasions and ritual use. Others, whether plain or patterned, are used as daily attire or for domestic purposes.

While the breadth of traditions across the subcontinent can be approached in many ways, textile scholar Ruchira Ghose offers us an accessible entry point through which we can classify textiles. Her approach is based on the stage of weaving at which designs or patterns are incorporated into the fabric. These classifications are:

- Pre-Loom: When patterns are predetermined on yarns that are dyed in specially formulated sections before they enter the loom.

- On-Loom: When plain and patterned textiles are woven on the loom with the use of threads of different colors and materials that can produce a number of designs and patterns based on various types of intersections between the warp and weft threads.

- Post-Loom: When finished textiles that are off the loom are decorated using techniques such as dyeing and embroidery.

For examples of specific types of textiles and fabrics, use the following link: Smarthistory – Practice and perfection: textile traditions

Copyright: The MAP Academy, “Practice and perfection: textile traditions,” in Smarthistory, February 10, 2023, accessed May 6, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/practice-and-perfection-textile-traditions/.

Painted and Printed Textiles

Video URL: https://youtu.be/5TlpaNB2gTI?si=lMBJMRs7KtI8svOF

Textiles and Royal Life

Video URL: https://youtu.be/VtuTCjEAlZ8?si=7RsL3ytUsKmmo_Eo

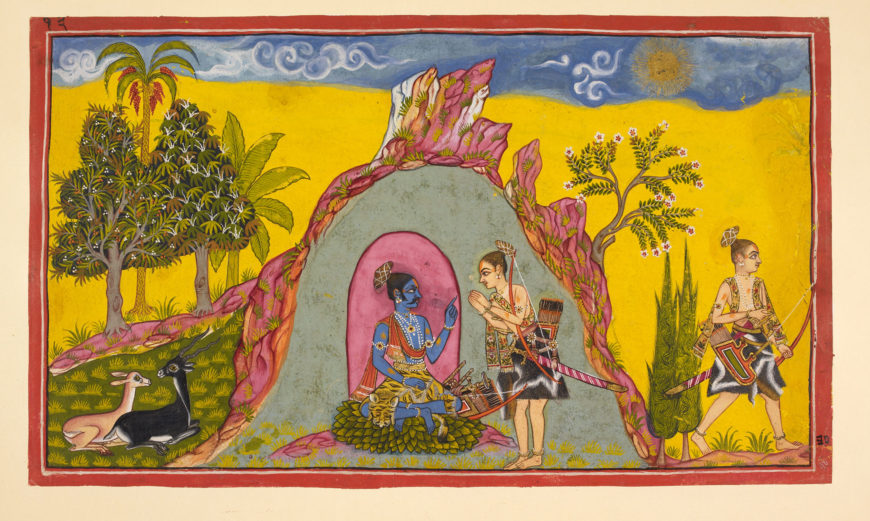

Divine “Blueness”

Unknown artist (Madhubani district, Mithila, Bihar, India), the Hindu god Krishna playing his flute while standing on the back of a multi-headed serpent (perhaps the demon Kaliya), mid-20th century, ink and color on paper, 27.9 x 44.1 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art)

“Why is Vishnu blue? Why is Krishna blue?” There are a variety of responses that can be found in the diverse literature and art of South Asia which can help us begin to answer these questions.

Representations of Vishnu. Left: Ceremonial Cover (Rumal): Vishnu on the Cosmic Ocean, late 18th or early 19th century, cotton plain weave with silk embroidery, made in Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, India (Philadelphia Museum of Art); right: Vishnu as Vishvarupa (cosmic or universal man), c. 1800–20, watercolour on paper, early 19th century, Jaipur, India (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

Vishnu has a blue or dark complexion because he reflects the color of the cosmos. Vishnu’s complexion is also understood to be the color of dark storm clouds and the color of the moon. Some scholars believe that Vishnu’s “blueness” is a result of Krishna’s dark complexion, as Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu. In other words, it may be that Krishna’s “blueness” came first.

Different representations of Krishna. Left: detail from a painting of Krishna and Nikumba, Harivamsha, c. 1590 (Mughal Empire), opaque watercolor and gold on paper (Victoria & Albert Museum, London); center: detail of Ceremonial Cloth with the Ten Avatars (Dasavataras) of Krishna, first half of 19th century, silk plain weave with discontinuous interlocking weft, Assam, India (Philadelphia Museum of Art); and right: Krishna Playing the Flute (Venugopala), c. 1920, phyllite with pigment, Calcutta (present-day Kolkata), West Bengal, Bengal Region, India (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Krishna is known as “the dark one” and his name translates as “black” or “dark” in Sanskrit (also spelled Kṛṣṇa).

According to Hinduism, Vishnu (and by extension Krishna) is the cosmic or divine power of the “Dark Age” or Kali Yuga. Some believe that Vishnu previously appeared in different forms (and with different complexions) during previous ages (yugas) of the universe: white in Krita Yuga, yellow in Dwaparaa Yuga, red in Treta Yuga, and black in Kali Yuga. Accordingly, Vishnu’s (and Krishna’s) appearance during the Kali Yuga is “black” in complexion.

In artistic renderings—whether on paper, stone, or cloth—Krishna’s “dark” skin appears in a variety of shades from pale silvery blue to midnight black. In fact, different artists interpreted the exact hue of Krishna’s complexion in different ways, depending on region and time period. Some stories describe Krishna’s birth occurring at night and during the late August / early September monsoon storm season. So, Krishna’s dark skin reflects both the time of his birth and the color of monsoon clouds. Krishna’s physical appearance reflects the geography of his hometown of Brindaban and the region where he grew up, a place known as Braj. Accordingly, his body is the color of the landscape of Braj, dark like the surrounding mountains. Krishna’s complexion may also be related to moments during his life when he drank poison as an attempt to vanquish evil forces or purify the world. One story related to Krishna as a baby describes him sucking the poisoned milk from a bird-demoness who disguised herself as a beautiful woman and visited the baby soon after he was born, in an attempt to kill him. Some believe the poison caused his skin to turn dark or blue.

Rama, the protagonist of the epic story the Ramayana, similarly appears in artistic renderings and textual descriptions as having a dark complexion. Rama’s dark skin (often depicted as blue) connects him to the divinity of Vishnu.

In addition to Vishnu (and his avatars including Krishna and Rama), many divine figures in Hinduism are depicted with dark complexions. For example the fierce form of the mother goddess known as Kali (a name which translates as “black”) often appears with jet black skin. The god Shiva often appears with ashy blue-gray skin, perhaps a result of his ascetic nature and spending time at cremation grounds. The Princess Draupadi (an important female character in the Mahabharata) is described as having skin the color of a “blue lotus” and is sometimes referred to as the “dark beauty.” The author of the Mahabharata, the sage Vyasa, is also described as having a dark (“krishna-like”) complexion.

Blue minerals and pigments—such as aquamarine, indigo, and lapis lazuli—have long been culturally and commercially valuable materials, not only in South Asia, but also around the world. The choice to depict Krishna as blue (rather than black) may have been a result of the availability and popularity of these materials.

While we don’t necessarily know what the term Kṛṣṇa meant to early artists (“black,” “dark blue,” “green-blue” etc.), it is clear that specific colors have been used for centuries in South Asia to convey information about artistic and religious subjects. Whether creating objects and depictions for use in Hinduism, Esoteric Buddhism, or Jainism, artists were conscious and intentional about which colors to use when depicting divine and sacred figures.

Copyright: Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi, “Understanding divine “blueness” in South Asia,” in Smarthistory, August 15, 2021, accessed May 2, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/understanding-divine-blueness-in-south-asia/.