18 EASTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

The Silk Road

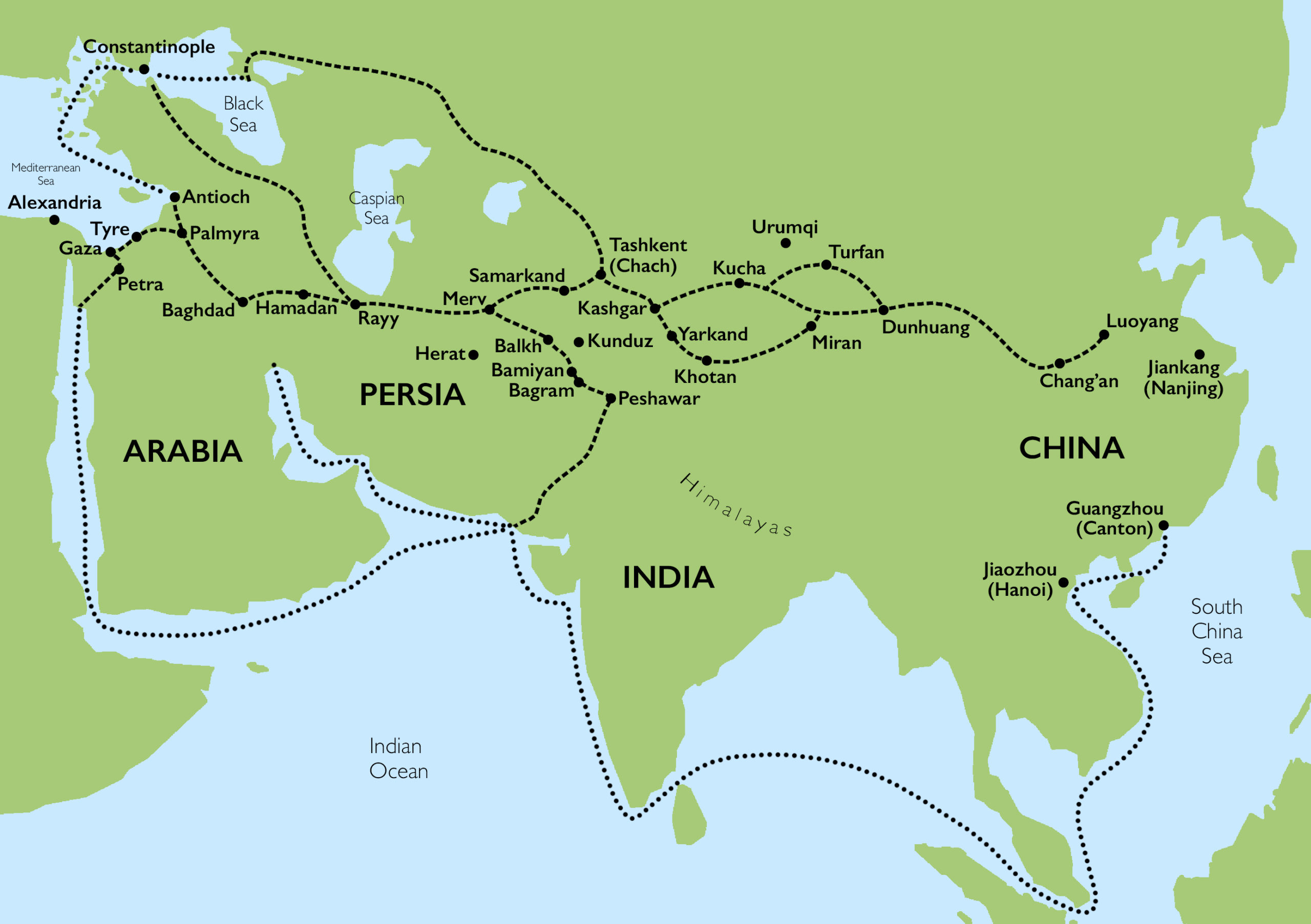

The name “Silk Road” is familiar to many, conjuring up caravan trains of camels crossing deserts weighed down by exotic goods such as tea, spices, medicines, and crucially, silk, but the reality of the Silk Roads was both more complex and more ordinary. The Silk Roads were a network of trade routes that connected towns and peoples across Asia that flourished from about 200–900 C.E. but existed from about 100 B.C.E. through the mid-1400s C.E. The foundation of the “Silk Roads” is attributed to Han dynasty envoy, Zhang Qian, whose mission to Central Asia in 114 B.C.E. brought the Chinese court into direct contact with kingdoms in Central Asia.The phrase “Silk Road,” invokes a pre-modern cross-continental highway, but the idea of a road meandering across Asia is relatively recent. The name “Silk Road” was given to the network of ancient trade routes crossing Asia by the German traveler and geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. Goods (including art objects, textiles, medicine, and foods) and ideas (including religious thought and philosophical concepts) certainly traveled very impressive distances along these trade routes, but most of the travel was relatively local in scope.

Many of the same routes continued to be used by later traders and travelers, but the combination of short and long-distance trade that characterized these overland routes shifted beginning in the 10th century. This occurred for several reasons, including the fall of the Tang dynasty in China; the rise of maritime trade routes through Southeast Asia that allowed for goods and people to travel long distances much more quickly; and the absorption of communities of Sogdians, merchants who were responsible for much of the long-distance Silk Road trade, by Islamic empires. Pan-Asian exchange flourished again in the Mongol period in the 13th and 14th centuries which saw Mongol rule over most of Asia, sometimes following the old Silk Roads overland, sometimes following the maritime trade routes that had been established between the decline of the overland Silk Roads and rise of the Mongols.

Asia is the primary focus of Silk Road trade, but it can be argued that the Silk Roads extended as far west as Rome, as attested by the presence of Roman glass bowls and other objects found in tombs in China and the Korean peninsula. Chinese silk was also highly sought after by Roman elites beginning as early as the second century B.C.E. Beginning in the fourth century C.E., the interconnectivity between Central Asia and the Eastern Roman Empire, which brought Asian goods into the Mediterranean, can also be understood as part of the Silk Roads.

Spread of Buddhism

Many ideas and philosophical concepts were carried along the Silk Roads. Buddhism was arguably the most far-reaching of these. Buddhism originated in India in the 5th or 4th century B.C.E., and soon spread out of India to the east and west via the Silk Roads, arriving in China sometime in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.– 220 C.E.). Some of the earliest Buddhist art objects to arrive in China were portable Buddhas brought from Central Asia to China by Buddhist monks, which may have served as objects of personal devotion.

The paintings and sculpture at these sites tell the story of different artistic traditions that came together along the Silk Roads, including inspiration from Greek art via Gandhara (in present-day north India and Pakistan). Most impressive are the monumental Buddhas found in several of the most prominent of these cave temple complexes, notably Bamiyan (tragically, the two monumental Buddhas were destroyed in 2001), Longmen, and Yungang in China.The introduction of Buddhism into China, and then to Korea and Japan was not a smooth and linear process but took place over hundreds of years, with Buddhism falling in and out of favor over the centuries. However, during the height of the Silk Road, Buddhism enjoyed support among Chinese elites. In particular, the cave temples at Luoyang and Yungang were important sites of Chinese imperial patronage of Buddhism during the Northern dynasties period into the Tang dynasty (618–906).

Copyright: Dr. Eiren Shea, “The Silk Roads,” in Reframing Art History, Smarthistory, August 19, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/reframing-art-history/the-silk-roads/.

The Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (618–907) is considered a golden age in Chinese history. It succeeded the short-lived Sui dynasty (581–618), which reunified China after almost four hundred years of fragmentation. The Tang benefited from the foundations the Sui had laid, and they built a more enduring state on the political and governmental institutions the Sui emperors established. Known for its strong military power, successful diplomatic relationships, economic prosperity, and cosmopolitan culture, Tang China was, without doubt, one of the greatest empires in the medieval world.

During the Tang dynasty, China stretched its territory (including the protectorate states) from the Korean peninsula in the east, to the steppes of Mongolia in the north, to present-day Afghanistan in the west, and to northern Vietnam in the south. Tang secured peace and safety on overland trade routes—the Silk Road—that reached as far as Rome. Merchants, diplomats, and pilgrims came from all over East and Central Asia. They brought with them new religions, ideas, and cultural practices that were eagerly embraced by Tang elite circles. The two capital cities of Chang’an and Luoyang were flooded with foreigners from different parts of the world.

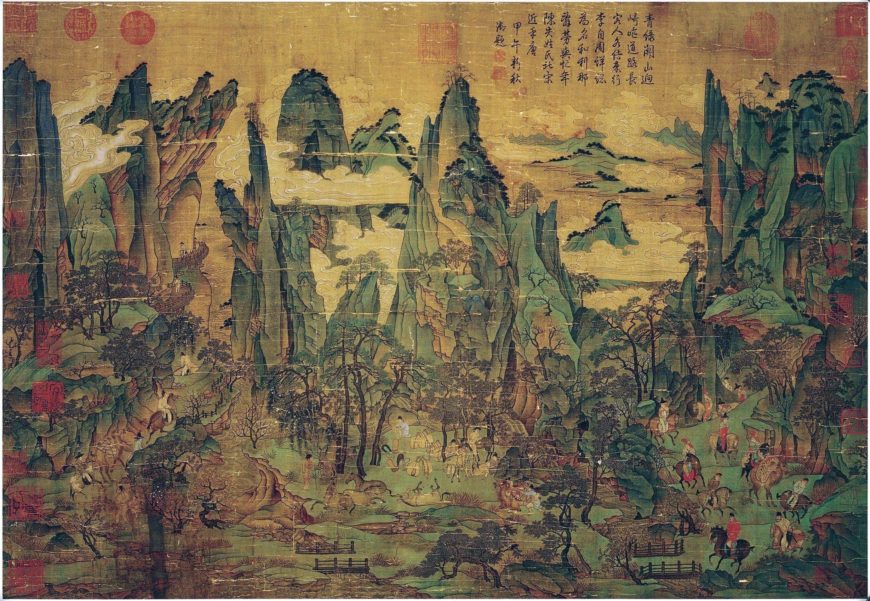

Tang painting prospered, partly thanks to the patronage of the Tang court. Painters from all over the empire were attracted to the court. Figure painting thrived during this period. Famous court painters established themselves with their masterful drawing skills. For example, Yan Liben (c. 601–673) was known for his rich and glowing colors and delicate details; while Wu Daozi (c. 680–759) was famous for his vigorous brushwork. Landscape painting took two directions during the Tang. One was a style of painting known as blue-green landscape developed by the court painters, executed in fine lines with added mineral colors. It may have been inspired by Central Asian painting styles. The other was the monochrome ink painting developed by the poet-painter Wang Wei (701–761). This style was favored by the newly emerging social elite who became government officials through the official examination system. The division between the two styles became more apparent during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Besides their excellent painting skills, many of the cultivated scholar-officials were also great poets and calligraphers. The three arts—painting, poetry, and calligraphy—have since been connected and appreciated as “the three perfections.”

Copyright: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, “Tang dynasty (618–907), an introduction,” in Smarthistory, April 23, 2021, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/tang-dynasty-intro/.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

LITERATURE

Tang Poetry

During the Tang Dynasty, over 48,900 poems were written in what was the height of the golden age of Chinese poetry. Tang poetry is typically characterized by a short number of lines, a strong connection to religion (usually Confucianism or Daoism), captures everyday lives of the Chinese people, and connects to nature. Li Bai, a Daoist, and Du Fu, a Confucian, both living in the early 8th century, use Zhou anthologies of poems to inspire their Tang poetry. Li Bai’s poems mainly connect to nature, friendship, and solitude while Du Fu, who was a civil servant, included more technical precision in his poetry.

The seven forms of Tang Poetry are:

- Five-character-ancient-verse

- Five-character-regular-verse

- Five-character-quatrain

- Seven-character-ancient-verse

- Seven-character-regular-verse

- Seven-character-quatrain

- Folk-song-styled-verse

Five-character-ancient-verse

Li Bai DRINKING ALONE WITH THE MOON

From a pot of wine among the flowers

I drank alone. There was no one with me —

Till, raising my cup, I asked the bright moon

To bring me my shadow and make us three.

Alas, the moon was unable to drink

And my shadow tagged me vacantly;

But still for a while I had these friends

To cheer me through the end of spring….

I sang. The moon encouraged me.

I danced. My shadow tumbled after.

As long as I knew, we were boon companions.

And then I was drunk, and we lost one another.

…Shall goodwill ever be secure?

I watch the long road of the River of Stars.

Du Fu A VIEW OF TAISHAN

What shall I say of the Great Peak? —

The ancient dukedoms are everywhere green,

Inspired and stirred by the breath of creation,

With the Twin Forces balancing day and night.

…I bare my breast toward opening clouds,

I strain my sight after birds flying home.

When shall I reach the top and hold

All mountains in a single glance?

Five-character-regular-verse

Li Bai A MESSAGE TO MENG HAORAN

Master, I hail you from my heart,

And your fame arisen to the skies….

Renouncing in ruddy youth the importance of hat and chariot,

You chose pine-trees and clouds; and now, whitehaired,

Drunk with the moon, a sage of dreams,

Flower- bewitched, you are deaf to the Emperor….

High mountain, how I long to reach you,

Breathing your sweetness even here!

Du Fu ON A MOONLIGHT NIGHT

Far off in Fuzhou she is watching the moonlight,

Watching it alone from the window of her chamber-

For our boy and girl, poor little babes,

Are too young to know where the Capital is.

Her cloudy hair is sweet with mist,

Her jade-white shoulder is cold in the moon.

…When shall we lie again, with no more tears,

Watching this bright light on our screen?

Five-character-quatrain

Li Bai IN THE QUIET NIGHT

So bright a gleam on the foot of my bed —

Could there have been a frost already?

Lifting myself to look, I found that it was moonlight.

Sinking back again, I thought suddenly of home.

Du Fu THE EIGHT-SIDED FORTRESS

The Three Kingdoms, divided, have been bound by his greatness.

The Eight-Sided Fortress is founded on his fame;

Beside the changing river, it stands stony as his grief

That he never conquered the Kingdom of Wu.

Seven-character-ancient-verse

Li Bai PARTING AT A WINE-SHOP IN NANJING

A wind, bringing willow-cotton, sweetens the shop,

And a girl from Wu, pouring wine, urges me to share it

With my comrades of the city who are here to see me off;

And as each of them drains his cup, I say to him in parting,

Oh, go and ask this river running to the east

If it can travel farther than a friend’s love!

Du Fu A SONG OF AN OLD CYPRESS

Beside the Temple of the Great Premier stands an ancient cypress

With a trunk of green bronze and a root of stone.

The girth of its white bark would be the reach of forty men

And its tip of kingfish-blue is two thousand feet in heaven.

Dating from the days of a great ruler’s great statesman,

Their very tree is loved now and honoured by the people.

Clouds come to it from far away, from the Wu cliffs,

And the cold moon glistens on its peak of snow.

…East of the Silk Pavilion yesterday I found

The ancient ruler and wise statesman both worshipped in one temple,

Whose tree, with curious branches, ages the whole landscape

In spite of the fresh colours of the windows and the doors.

And so firm is the deep root, so established underground,

That its lone lofty boughs can dare the weight of winds,

Its only protection the Heavenly Power,

Its only endurance the art of its Creator.

Though oxen sway ten thousand heads, they cannot move a mountain.

…When beams are required to restore a great house,

Though a tree writes no memorial, yet people understand

That not unless they fell it can use be made of it….

Its bitter heart may be tenanted now by black and white ants,

But its odorous leaves were once the nest of phoenixes and pheasants.

…Let wise and hopeful men harbour no complaint.

The greater the timber, the tougher it is to use.

Seven-character-regular-verse

Li Bai ON CLIMBING IN NANJING TO THE TERRACE OF PHOENIXES

Phoenixes that played here once, so that the place was named for them,

Have abandoned it now to this desolate river;

The paths of Wu Palace are crooked with weeds;

The garments of Qin are ancient dust.

…Like this green horizon halving the Three Peaks,

Like this Island of White Egrets dividing the river,

A cloud has arisen between the Light of Heaven and me,

To hide his city from my melancholy heart.

Du Fu THE TEMPLE OF THE PREMIER OF SHU

Where is the temple of the famous Premier? —

In a deep pine grove near the City of Silk,

With the green grass of spring colouring the steps,

And birds chirping happily under the leaves.

…The third summons weighted him with affairs of state

And to two generations he gave his true heart,

But before he could conquer, he was dead;

And heroes have wept on their coats ever since.

Seven-character-quatrain

Li Bai A FAREWELL TO MENG HAORAN ON HIS WAY TO YANGZHOU

You have left me behind, old friend, at the Yellow Crane Terrace,

On your way to visit Yangzhou in the misty month of flowers;

Your sail, a single shadow, becomes one with the blue sky,

Till now I see only the river, on its way to heaven.

Du Fu ON MEETING LI GUINIAN DOWN THE RIVER

I met you often when you were visiting princes

And when you were playing in noblemen’s halls.

…Spring passes…. Far down the river now,

I find you alone under falling petals.

Folk-song-styled-verse

Li Bai THE MOON AT THE FORTIFIED PASS

The bright moon lifts from the Mountain of Heaven

In an infinite haze of cloud and sea,

And the wind, that has come a thousand miles,

Beats at the Jade Pass battlements….

China marches its men down Baideng Road

While Tartar troops peer across blue waters of the bay….

And since not one battle famous in history

Sent all its fighters back again,

The soldiers turn round, looking toward the border,

And think of home, with wistful eyes,

And of those tonight in the upper chambers

Who toss and sigh and cannot rest.

Du Fu A SONG OF SOBBING BY THE RIVER

I am only an old woodsman, whispering a sob,

As I steal like a spring-shadow down the Winding River.

…Since the palaces ashore are sealed by a thousand gates —

Fine willows, new rushes, for whom are you so green?

…I remember a cloud of flags that came from the South Garden,

And ten thousand colours, heightening one another,

And the Kingdom’s first Lady, from the Palace of the Bright Sun,

Attendant on the Emperor in his royal chariot,

And the horsemen before them, each with bow and arrows,

And the snowy horses, champing at bits of yellow gold,

And an archer, breast skyward, shooting through the clouds

And felling with one dart a pair of flying birds.

…Where are those perfect eyes, where are those pearly teeth?

A blood-stained spirit has no home, has nowhere to return.

And clear Wei waters running east, through the cleft on Dagger- Tower Trail,

Carry neither there nor here any news of her.

People, compassionate, are wishing with tears

That she were as eternal as the river and the flowers.

…Mounted Tartars, in the yellow twilight, cloud the town with dust.

I am fleeing south, but I linger-gazing northward toward the throne.

Poems Copyright: University of Virginia 1997, Home of 300 Tang Poems (virginia.edu)

ARCHITECTURE

Buddhist Cave Shrines

Video URL: https://youtu.be/9bE-n0n2BBA?si=kbuzeHrVsPXmTK9S

Asian Art Museum, “Chinese Buddhist cave shrines,” in Smarthistory, January 28, 2016, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/chinese-buddhist-cave-shrines/.

Todai-ji

When completed in the 740s, Tōdai-ji (or “Great Eastern Temple”) was the largest building project ever on Japanese soil. Its creation reflects the complex intermingling of Buddhism and politics in early Japan. When it was rebuilt in the twelfth century, it ushered in a new era of Shōguns and helped to found Japan’s most celebrated school of sculpture. It was built to impress. Twice.The roots of Tōdai-ji are found in the arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the sixth century. Buddhism made its way from India along the Silk Route through Central Asia, China and Korea. Mahayana Buddhism was officially introduced to the Japanese Imperial court around 552 by an emissary from a Korean king who offered the Japanese Emperor Kimmei a gilded bronze statue of the Buddha, a copy of the Buddhist sutras (sacred writings) and a letter stating: “This doctrine can create religious merit and retribution without measure and bounds and so lead on to a full appreciation of the highest wisdom.”

Buddhism quickly became associated with the Imperial court whose members became the patrons of early Buddhist art and architecture. This connection between sacred and secular power would define Japan’s ruling elite for centuries to come. These early Buddhist projects also reveal the receptivity of Japan to foreign ideas and goods—as Buddhist monks and craftspeople came to Japan.

Buddhism’s influence grew in the Nara era (710–94) during the reign of Emperor Shōmu and his consort, Empress Komyo who fused Buddhist doctrine and political policy—promoting Buddhism as the protector of the state. In 741, reportedly following the Empress’ wishes, Shōmu ordered temples, monasteries and convents to be built throughout Japan’s 66 provinces. This national system of monasteries, known as the Kokubun-ji, would be under the jurisdiction of the new imperial Tōdai-ji (“Great Eastern Temple”) to be built in the capital of Nara.

Building Tōdai-ji

Why build on such an unprecedented scale? Emperor Shōmu’s motives seem to have been a mix of the spiritual and the pragmatic: in his bid to unite various Japanese clans under his centralized rule, Shōmu also promoted spiritual unity. Tōdai-ji would be the chief temple of the Kokubun-ji system and be the center of national ritual. Its construction brought together the best craftspeople in Japan with the latest building technology. It was architecture to impress—displaying the power, prestige and piety of the imperial house of Japan.

However the project was not without its critics. Every person in Japan was required to contribute through a special tax to its construction and the court chronicle, the Shoku Nihon-gi, notes that, “the people are made to suffer by the construction of Tōdai-ji and the clans worry over their suffering.”

Bronze Buddha

Tōdai-ji included the usual components of a Buddhist complex. At its symbolic heart was the massive hondō (main hall), also called the Daibutsuden (Great Buddha Hall), which when completed in 752, measured 50 meters by 86 meters and was supported by 84 massive cypress pillars. It held a huge bronze Buddha figure (the Daibutsu) created between 743 to 752. Subsequently, two nine-story pagodas, a lecture hall and quarters for the monks were added to the complex.

Buddhism, Emperor Shomu and the creation of Tōdai-ji

The statue was inspired by similar statues of the Buddha in China and was commissioned by Emperor Shōmu in 743. This colossal Buddha required all the available copper in Japan and workers used an estimated 163,000 cubic feet of charcoal to produce the metal alloy and form the bronze figure. It was completed in 749, though the snail-curl hair (one of the 32 signs of the Buddha’s divinity) took an additional two years.

When completed, the entire Japanese court, government officials and Buddhist dignitaries from China and India attended the Buddha’s “eye-opening” ceremony. Overseen by the Empress Koken and attended by the retired Emperor Shōmu and Empress Komyo, an Indian monk named Bodhisena is recorded as painting in the Buddha’s eyes, symbolically imbuing it with life. The Emperor Shōmu himself is said to have sat in front of Great Buddha and vowed himself to be a servant of the Three Treasures of Buddhism: the Buddha, Buddhist Law, and Buddhist Monastic Community. No images of the ceremony survive but a Nara period scroll painting depicts a sole, humbly small figure at the Daibutsu‘s base suggesting its awe-inspiring presence.

The Daibutsu sits upon a bronze lotus petal pedestal that is engraved with images of the Shaka (the historical Buddha, known also as Shakyamuni) Buddha and varied Bodhisattvas (sacred beings). The petal surfaces are etched with fleshy figures with swelling chests, full faces and swirling drapery in a style typical of the elegant naturalism of Nara era imagery. The petals are the only reminders of the original statue, which was destroyed by fire in the twelfth century. Today’s statue is a seventeenth-century replacement but remains a revered figure with an annual ritual cleaning ceremony each August.

The grand Buddhist architectural and sculptural projects of early Japan share a common material—wood—and are thus closely linked to the natural environment and to the long history of wood craftsmanship in Japan.When Korean craftsmen brought Buddhist temple architecture to Japan in the sixth century, Japanese carpenters were already using complex wooden joints (instead of nails) to hold buildings together. The Koreans’ technology allowed for the support of larger, tile-roof structures that used brackets and sturdy foundation pillars to funnel weight to the ground. This technology ushered in a new, larger scale in Japanese architecture.

Monumental timber framed architecture requires enormous amounts of wood. The wood of choice was cypress, which grows up to forty meters tall and has a straight tight grain that easily splits into long beams and is resistant to rot.

The eighth-century campaign to construct Buddhist temples in every Japanese province under Imperial control (mostly in the Kinai area, today home to Osaka and Kyoto) is estimated to have resulted in the construction 600–850 temples using three million cubic meters of wood. As the years progressed Kinai’s old growth forests were exhausted and builders had to travel farther for wood.

By far the most prestigious and wood-demanding project was the Imperial monastery of Tōdai-ji. Eighth-century Tōdai-ji had two 9-story pagodas and a 50 x 86 meter great hall supported by 84 massive cypress pillars that used at least 2200 acres of local forest. After Tōdai-ji’s destruction in 1180, it was rebuilt under the supervision of the monk Chogen, who solicited aid from all over Western Japan. Builders had to travel hundreds of kilometers from Kinai to find suitable wood. Whole forests were cleared to find tall cypresses for pillars, which were then transported at great cost: 118 dams were built to raise river levels in order to transport the massive pillars. And that was only the pillars—wood for the rest of the structure came from at least ten provinces.

Tōdai-ji’s reconstructed main hall was only half the size of the original and its pagodas several stories shorter. The availability or scarcity of quality local wood was a major factor in the design and evolution of architecture in Japan. For example, the growing scarcity of cypress of structural dimensions led to innovations that allowed carpenters to work with less straight-grained woods, like red pine and zelkova.

Copyright: Dr. Deanna MacDonald, “Tōdai-ji,” in Smarthistory, November 27, 2015, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/todai-ji/.

Stone Pagodas (Korea)

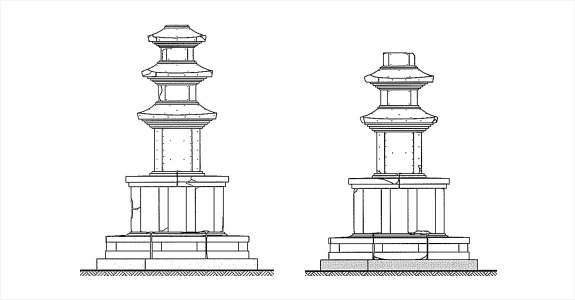

Same beautiful proportions as Seokgatap Pagoda

The style of Korean stone pagodas changed significantly in the seventh century, after Silla’s unification of the Three Kingdoms. The various existing styles of Silla and Baekje pagodas were incorporated into the Unified Silla style, as exemplified by the three-story stone pagodas of Gameunsa Temple and Goseonsa Temple in Gyeongju, which were built around the late seventh century. As if symbolizing the authority and grandeur of the newly unified kingdom, these pagodas impart a sense of stability and majesty. The lower half of the pagodas (i.e., the platform and the first story) was shaped roughly like a triangle with a wide base, while the upper half (i.e., the second and third stories) gradually decreased in proportion moving up to the roof.

However, the stable stone pagodas of the early Unified Silla period quickly changed, as the overall proportions became longer and thinner, even as the overall size decreased, and the base of the lower triangle became narrower. Also, the stones were combined and placed with more precision and efficiency. By the mid-eighth century, Silla stone pagodas reached the peak of their beauty, as epitomized by Seokgatap Pagoda, with the lower half shaped like an equilateral triangle and a superb rate of decrement moving up towards the top. Pagodas with these proportions were enormously popular not only in the Silla capital of Gyeongju, but also in the regional provinces.

Although some parts of the east and west stone pagodas from the site of Galhangsa Temple are missing, they still show almost the same lovely proportion as Seokgatap Pagoda, indicating that they were produced around the same time period.

Nail holes

Interestingly, both of these pagodas have numerous nail holes all over their surface, a detail that is not seen on Seokgatap Pagoda and has rarely been seen on other typical stone pagodas with a similar form that were produced in the previous era.

From the late seventh century to the mid-eighth century, nails or spikes were rarely used on stone pagodas, except perhaps to attach a wind chime to a roof stone. However, the stone pagoda from the site of Goseonsa Temple, which is estimated to have been made slightly earlier, also has nail holes on the surface. The nail holes were likely used to attach ornaments, such as metal plates, to the pagoda.

This raises an interesting question: why would two pagodas in a relatively remote location (Gimcheon, North Gyeongsang Province) be covered with such decorations? The inscription states that the two pagodas from Galhangsa Temple were built in 758, and that information corresponds to the arrangement and proportion of materials in the platform. Two similar pagodas can be found at the reported site of Inyongsa Temple in Gyeongju, and they also have nail holes. The east and west stone pagodas from Inyongsa Temple, which are estimated to date from the late eighth century, have been badly damaged over the years, but their roof stones and the body of the stones in the first story are similar to the pagodas from Galhangsa Temple. Although the arrangement of nail holes on the roof stone is different from the Galhangsa Temple pagodas, both sets of pagodas have holes along the edge at regular intervals. Thus, based on the surface decorations, the Inyongsa Temple pagodas seem to have been constructed after the Goseonsa Temple pagoda (prior to the late seventh century), but before the Galhangsa Temple pagodas (758).In fact, however, the Inyongsa Temple pagodas are estimated to have been produced in the late eighth century, and the Galhangsa Temple pagodas were produced in 758.

This discrepancy forces us to reconsider the circumstances of the inscription on the Galhangsa Temple pagodas. The inscription can be translated as follows:

These two pagodas were completed in 758, thanks to the good deeds of one brother and two sisters: the brother is Monk Eonjeok of Yeongmyosa Temple in Gyeongju; the older sister is Queen Somun; the younger sister is the maternal aunt of Great King Gyeongsin.

(二塔天寶十七年戊戌中立在之 娚女市妹三人業以成在之 娚者零妙寺言寂法師在 女市者照文皇太后君妳在 妹者敬信太王妳在也)

The names “Great King Gyeongsin” (敬信太王) and “Queen Somun” are also recorded in History of the Three Kingdoms, in reference to King Wonseong and his mother. Notably, the inscription refers to him as the king, and uses the name “Gyeongsin,” as he was known during his lifetime; “King Wonseong” is an honorary title that was posthumously granted to him. Thus, the inscription must have been carved during the reign of King Wonseong, from 785 to 798.

But why wouldn’t the patrons have made the inscription in 758, at the time that the pagodas were built? Then again, why did they feel the need to create the inscription many years later, and to mention their relation to the reigning king? One possible theory is that, after King Wonseong ascended to the throne, his maternal relatives celebrated his enthronement by making Buddhist dedications and offerings at Galhangsa Temple, the temple that was dedicated to their family. Although the details of these dedications and offerings are not known, the nail holes and the inscription may provide some important clues.

Perhaps the nail holes, a unique feature of the Galhangsa Temple pagodas, were newly added when surface decorations were attached to the pagodas during the reign of King Wonseong. The general arrangement of the decorations and nail holes may have been based on the Inyongsa Temple pagodas, which were built near the city wall in Silla’s capital. This hypothesis would resolve the aforementioned discrepancy caused by the surface decorations.

PERFORMING ARTS

Music

Classical Chinese Music

Chinese music is a rich and diverse tradition that has evolved over thousands of years. It encompasses a wide range of musical styles, instruments, and forms, including traditional Chinese instruments like the erhu, guzheng, and dizi, as well as more modern instruments like the piano and guitar. Chinese music is characterized by its use of pentatonic scales and complex rhythms, as well as its emphasis on melody and expressiveness. Traditional Chinese music is often associated with specific occasions, such as weddings and religious ceremonies, and is often accompanied by dance or other performances. In recent years, Chinese music has also been influenced by Western styles, resulting in the emergence of a vibrant contemporary music scene in China.

Chinese traditional music is based on a pentatonic scale, which is a five-note scale. The most used pentatonic scale in Chinese music is the gong hexatonic scale, which consists of the notes C, D, E, G, A, and C. This scale is often used in solo instrumental and vocal music.

In addition to the pentatonic scale, Chinese music also uses various modes, which are similar to Western modes such as major and minor. Some of the most common modes used in Chinese music include the Zhi mode, the Yu mode, and the Shang mode. Each of these modes has its own unique characteristics and is used in different types of music.

The Zhi mode is often used in folk music and has a bright and lively character. The Yu mode is used in slower, more contemplative music and is often associated with sadness and longing. The Shang mode is used in more formal and ceremonial music and has a more serious and dignified character.

Overall, the scales and modes used in Chinese music are an integral part of its unique character and help to create the diverse range of emotions and feelings expressed in the music.

There are many traditional Chinese instruments, some of the most well-known include:

Guqin – a seven-stringed zither

Guzheng – a plucked zither with up to 21 strings

Erhu – a two-stringed fiddle

Pipa – a four-stringed lute

Dizi – a flute

Yangqin – a hammered dulcimer

Sheng – a mouth organ

Xiao – end-blown bamboo flute

Ruan – a plucked lute

These instruments have a long history and are an important part of Chinese culture and music. They are used in traditional Chinese music, as well as in contemporary and fusion music.

A Chinese orchestra typically consists of a variety of traditional Chinese instruments, including string instruments such as the erhu and guzheng, wind instruments like the dizi and suona, and percussion instruments like the gong and drum. These instruments are combined to create a unique and distinct sound that is associated with traditional Chinese music. The orchestra may also include a conductor and a vocalist who performs traditional Chinese songs and operas. The ensemble typically plays both traditional Chinese music and contemporary pieces that are based on traditional Chinese music.

Watch a short video of Tradition Chinese Music from the Kennedy Center

Chapter 4: The Music of China Copyright © 2023 by Antoni Pizà is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Theater

Beijing Opera

Video URL: https://youtu.be/yzAdZDK4XKA?si=8Z4AYzo1u47FX4hZ

VISUAL ARTS

Haniwa Warrior

Video URL: https://youtu.be/pCpiIPj7xgI?si=JygF0GrGC9JSLwTC

Haniwa (“clay cylinder” or “circle of clay” in Japanese) are large hollow, earthenware funerary objects found in Japan. Massive quantities of haniwa—many nearly life sized—were carefully placed on top of colossal, mounded tombs, known as kofun (“old tomb” in Japanese). During the Kofun Period (c. 250 to c. 600 C.E.), haniwa evolved in many ways—their shape, the way they were placed on the mounded tombs and, presumably, their specific function or ritual use.

We don’t know much about haniwa or the Kofun Period because there was no writing system in Japan at the time. However, there is general agreement that haniwa were meant to be seen. That is, instead of being buried deep underground with the deceased, haniwa occupied and marked the open surfaces of the colossal tombs. However, it is unlikely that they were readily visible to any person who happened to pass by since the tombs were sacred, ritualized spaces that were usually surrounded by one or more moats. As a result, close visual contact with haniwa would not have been easy for unauthorized visitors. So who was the intended audience of haniwa? Let’s explore further.

Monumental tombs and early Japan

Unlike many other ancient civilizations, we cannot rely on written records to inform us about the names or locations of the earliest kingdoms in Japan. Yet study of kofun indicate that a powerful state had emerged by around 250 C.E. This state is identified by various names (such as the Yamato polity), and was generally centered in what is now Nara, Kyoto, and Osaka prefectures.

We know that a powerful state emerged since vast resources were needed to construct these monumental tombs—starting with the economic means to sacrifice valuable flat land that could otherwise be used for farming and growing rice. Hundreds of workers were also necessary, and archaeologists excavating kofun have recovered pottery from neighboring locations such as present day Nagoya—suggesting that people came from elsewhere to Yamato to serve the needs of this early state.

Evolution and placement of haniwa

Closeup of the Warrior Haniwa

Starting with the visorless helmet, especially fascinating is the series of small, evenly spaced half-spherical rivets that appear on a raised section on top of the helmet, in addition to raised strips that connect the sides and front to a narrow band that circles around the forehead and continues behind the head. These rivets are believed to represent metal rivets, suggesting that the warrior’s head was protected by a metal helmet. Attached to the helmet are thick protective ear flaps, seemingly made of padded fabric or leather, while a sheet of thinner material wraps around the rest of the head and neck. Rivets also appear on the narrow quiver, containing four or more arrows, strapped to the warrior’s back.

The short-sleeved body armor that flares outward near the hips does not have rivets, but is covered by thin, vertically incised markings. Two large looped ties found on the chest suggest that this armor was laced together; whether the armor was made by stringing together thin iron plates is unclear based on the visual evidence, but remains as a possibility.

Copyright: Dr. Yoko Hsueh Shirai, “Haniwa Warrior,” in Smarthistory, November 27, 2015, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/haniwa-warrior/.

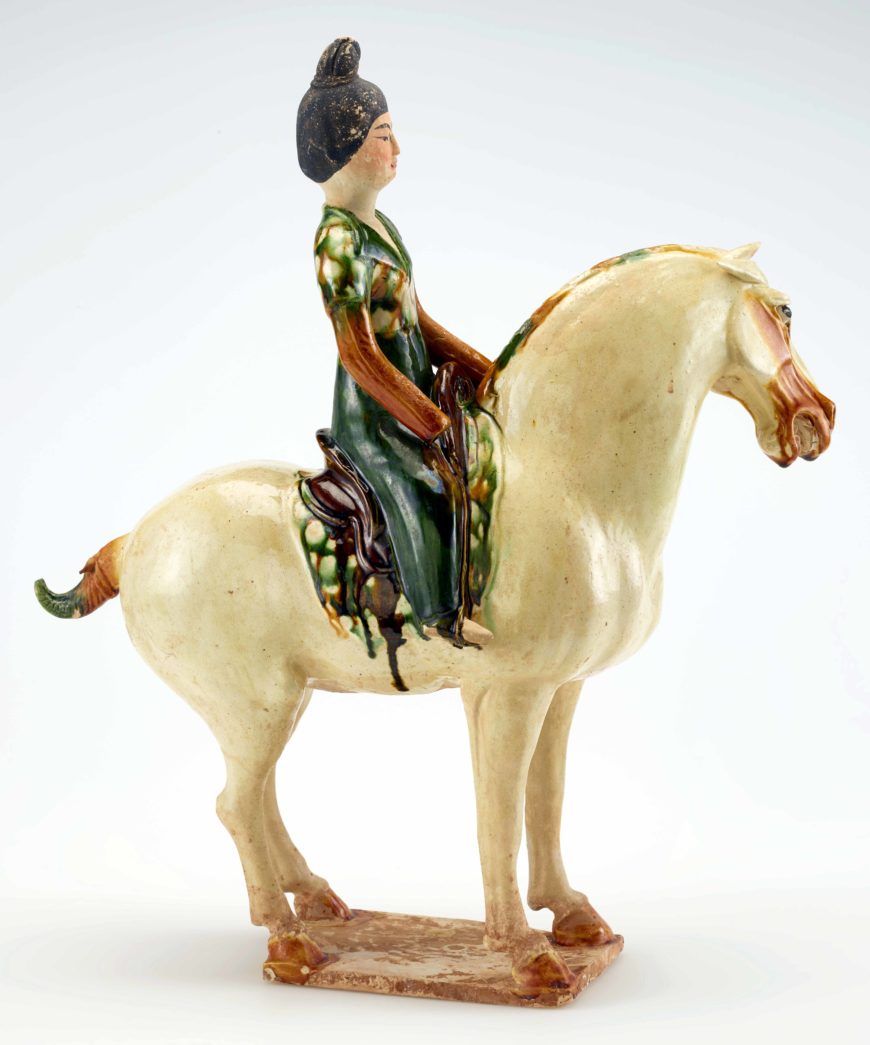

Tomb Figures

The pair of pottery male and female horse riders are vividly depicted. The man wears a heart-shaped hat, wide-sleeved green coat, and black boots. His arms are raised as if holding the rein. The woman, with a high-top knot, sits up straight on her horse. She wears a colorful, short-sleeved jacket and a pair of green trousers. The horses are depicted in lively poses. We can almost read their facial expressions.

The Tang dynasty (618–907) is famous for its sancai ceramics that prominently feature the colors white, green, and amber. The basic glaze is transparent, slightly white, and contains a mixture of lead oxide, silica, and alumina. It can be fired at temperatures between 650 and 1000 degrees centigrade. The color green was achieved by mixing copper oxide into this base glaze, and amber/yellowish brown was achieved by mixing in iron oxide. On rare occasions, expensive cobalt oxide was added as a glaze to generate blue. The clay body of many sancai wares is creamy white (sometimes enhanced by a white clay coating called “slip”), allowing the colored glazes to stand out vibrantly and thus making sancai ware one of the shining treasures of Chinese ceramics. Tang sancai wares are thought to have been reserved for burial use and were rarely, if ever, used in daily life.

Ancient Chinese believed in the existence of an afterlife. They made tomb figurines as replacements for real objects so that the deceased would enjoy their company or service in the afterlife. During the Tang dynasty, the use of sancai wares in tombs was restricted to people of a certain status. Furthermore, the number and size of the figures were determined by the rank of the deceased. As best we know, this pair of horse riders belong to a group of sixteen equestrian figures found in a tomb in northern China. They prove the high social status of the tomb owner and provide us with an intimate peek into certain aspects of the owner’s life.

Copyright: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, “Tomb figures of a man and woman on horseback,” in Smarthistory, July 6, 2021, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/tomb-figures-man-woman-on-horseback-tang/.

Chinese Scrolls

The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies is an eighth-century copy of the earliest and finest painting attributed to Gu Kaizhi (about 345–406). It illustrates a political parody written by Zhang Hua (about 232–300). The parody takes a moralizing tone, attacking the excessive behavior of an empress. The protagonist is the court instructress who guides the ladies of the imperial harem on correct behavior.

The handscroll has a complex, horizontal arrangement. Nine scenes illustrate the text, beginning from the right. There may have been three additional scenes and texts at the beginning of the scroll, which are now missing. It was re-mounted during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–95) as he greatly admired it. It was mounted in its current format at the British Museum in 1914, to preserve it more safely.

None of Gu Kaizhi’s original works has survived, but he has still acquired a legendary status, both as a painter and as a writer on Chinese painting. He was given extensive coverage in the dynastic histories and the seminal text on painting, Li-dai ming-hua ji written by Zhang Yanyuan (about 847). Gu Kaizhi’s reputation was probably helped by anecdotes about his eccentricity; he was said to have been perfect in ‘painting, literary composition and foolishness’.

This painting has been executed in a fine linear style that is typical of fourth-century figure painting. Similar pictorial motifs have been discovered in contemporary tombs. Texts describe Gu Kaizhi as having painted in this manner. The inscriptions and seals on this scroll date back to the eighth century, when this copy of Gu’s original was probably painted.

Before its arrival at the British Museum in 1903, the scroll passed through many hands. The history of the painting can be ascertained through the seals and inscriptions, beginning with the eighth-century seal of the Hongwen guan, a division of the Han-lin Academy.

The painting was subsequently in the collections of well-known connoisseurs who added their own seals and inscriptions, before ending up in the imperial collection during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (1736-96).

Copyright: The British Museum, “Admonitions Scroll, attributed to Gu Kaizhi,” in Smarthistory, February 26, 2021, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/admonitions-scroll-gu-kaizhi/.

Chinese Zither

This long, rectangular instrument is a zither, or qin in Chinese. It is extremely rare because not many musical instruments from this period still survive today. The scalloped outline (traditionally named “strung pearls”) and relatively thick sound box suggest it was made during the Song dynasty (960–1279) or earlier. The instrument has seven silk strings of varying thickness. The strings are mounted on a hollow, lacquered wooden box. Thirteen inlaid jade inserts run along the outer edge to indicate pitch positions and help the performer with finger placement.

Qin are one of the most ancient Chinese musical instruments, probably in use as early as the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 B.C.E.). When playing, the performer plucks the strings with the right hand and alters the pitch with the left. The design of a qin, such as its seven-string form, was standardized during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 C.E.). Qin owners and masters often incised the backboard of a treasured instrument with poetic writings, praising its venerable history and spiritual virtues. Unlike Western instruments that are often played in orchestras at large gatherings, qin are played mainly for personal enjoyment or for a small group of friends, often in private gardens.

Qin have for centuries been valued as a symbol of high culture by the Chinese elite class. Every scholar-gentleman is expected to be skilled in four art forms: qin (music), qi (chess), shu (calligraphy) and hua (painting). Qin playing is regarded as a spiritual and intellectual activity. It can help with self-cultivation and learning enhancement. In Chinese landscape paintings, sages and scholars are often seen playing qin while enjoying beautiful scenery.

Copyright: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, “Zither (qin) inscribed with the name “Dragon’s Moan”,” in Smarthistory, May 7, 2021, accessed April 23, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/zither-qin-inscribed-with-the-name-dragons-moan/.