37 CENTRAL ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

The Mughal Empire

Video URL: https://youtu.be/nbuM0aJjVgE?si=adgej_nMEmgDXSy2

British East India Company

Reports of the marvelous wealth of India and the riches amassed by Portuguese merchants encouraged the Europeans of other nations to seek their fortunes in the Indian Ocean. In 1600, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted a monopoly on trade in the Indian Ocean to the British East India Company (also known as the English East India Company or the East India Company).1 The British East India Company was a joint stock company in which numerous merchants pooled their money to fund trading voyages and share the profits. An expedition to India required an enormous outlay of money that few individuals could afford, and if they could, they might lose their entire fortunes if the expedition were unsuccessful. By pooling funds, none had to risk all they owned.

Dutch and French merchants also formed joint stock East India companies. While the Dutch focused most of their attention on the islands of Indonesia, France competed with England and Portugal to harvest the wealth of India. In 1661, Charles II of England received Bombay (Mumbai) as part of the dowry of his Portuguese wife, Catherine of Braganza, and leased it to the British East India Company. France, in turn, established a trading post at Surat in 1668 and founded others in the years that followed. Europeans often partnered with Indian merchants who sought new investment opportunities outside the subcontinent.

In 1685, the Mughal governor of Bengal increased taxes on English trade in the region. The British East India Company refused to pay and sought to wrest control of the territory from the Mughals. English ships blockaded Mughal ports on India’s west coast, interfering with both Mughal trade and the passage of Muslim pilgrims on their way to Mecca. In response, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb seized control of company possessions and, in 1689, began a blockade of Bombay, starving the English into submission. Company representatives were forced to pay a substantial fine before their trading privileges were returned to them.

In their attempt to resist English expansion, the Mughals turned to the French for assistance. Already rivals in trade, beginning in 1754 France and Britain found themselves enmeshed in a war in North America for control of that continent. This conflict, called the French and Indian War, soon spread to Europe where fighting broke out in 1756. As part of this now-global conflict, called the Seven Years’ War, French and British armies and navies engaged in battle in India as well. France allied itself with the Mughal Empire. In 1756, the French, who had greatly expanded their commercial activity in Bengal, pressured the region’s ruler to attack the British Fort William near Calcutta (Kolkata). The following year, the British struck back, defeating Bengali and French forces at the Battle of Plassey, allowing the British to trade unopposed in Bengal. In 1761, the British destroyed the French post of Pondicherry (Puducherry).

With both the Mughals and the Marathas weakened after years of combat with one another as well as with invading Afghans and encroaching Europeans, small states in northern India broke away from their control and recognized British authority in exchange for acknowledgment of their claims to rule. The chaos that ensued helped the British in their quest to gain control of India. In this way, through a combination of alliances and military victories and the use they made of existing divisions between its kingdoms and rulers, the British gradually gained control of India.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). India and International Connections. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Sikhism

The religion of Sikhism, a monotheistic faith that combines elements of Hinduism and Islam, was established in the Punjab region of northwestern India in the fifteenth century. Sikhs regard Guru Nanak (1469–1539 CE) as the founder of their faith and Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708 CE), the tenth Guru, as the Guru who formalized their religion. Religions and religious teachers do not exist in a vacuum: India, in the Gurus’ time, was ruled by Mughal emperors who were Muslim. Punjabi society was a mix of Muslims and Hindus.

The Sikh religion has evolved from the Gurus’ teachings, and from their followers’ devotion, into a world religion with its own scripture, code of discipline, gurdwaras (places of worship), festivals and life cycle rites and Sikhs share in a strong sense of identity and celebrate their distinctive history. A central principle of the Gurus’ teaching is the importance of integrating spirituality with carrying out one’s responsibilities. Sikhs should perform seva (voluntary service of others) while at the same time practicing simaran (remembrance of God). The ideal is to be a sant sipahi (warrior saint) i.e. a person who combines spiritual qualities with a readiness for courageous action. Guru Nanak, the first Guru, and Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru, continue to feature prominently in Sikhs’ experience of their religion.

Who was Guru Nanak?

Sikhs explain ‘Guru’ as meaning ‘remover of darkness’. There have been just ten human Gurus. Their lives spanned the period from Nanak’s birth in 1469 to the passing away of Guru Gobind Singh in 1708. Since then the Sikhs’ living Guru has been the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred volume of scripture. The Guru Granth Sahib is much more than a book: it is believed to embody the Guru as well as containing compositions by six of the ten Gurus. The preeminent Guru (Nanak’s Guru) is God, whose many names include ‘Satguru’ (the true Guru) and ‘Waheguru’ (a name which began as an exclamation of praise).

Guru Nanak was born in 1469 in Talvandi, a place now renamed Nankana Sahib, in the state of Punjab in present-day Pakistan. His parents were Hindus and they were Khatri by caste, which meant that they had a family tradition of account-keeping. The name ‘Nanak’, like Nanaki, his sister’s name, may indicate that they were born in their mother’s parents’ home, known in Punjabi as their nanake. Guru Nanak’s wife was called Sulakhani and she bore two sons. Until a life-changing religious experience, Nanak was employed as a store keeper for the local Muslim governor.

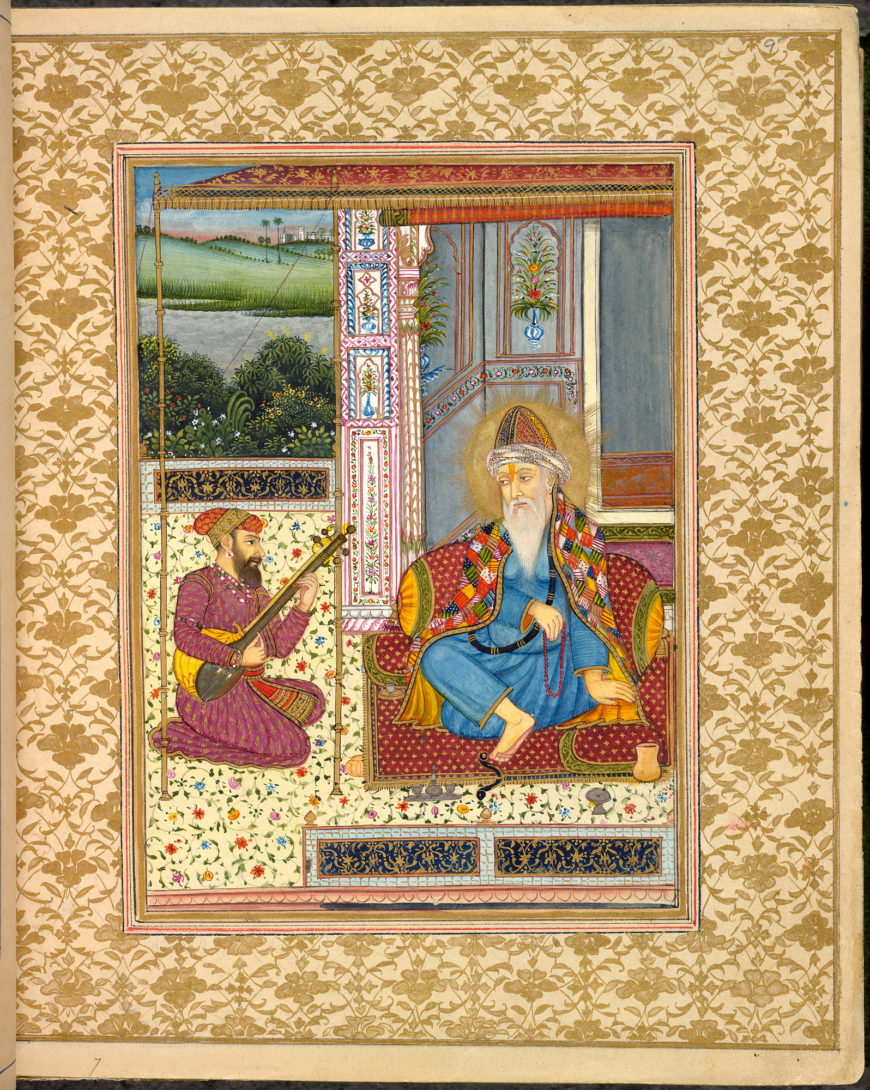

One day, when he was about thirty, he experienced being swept into God’s presence, while he was having his daily bath in the river. The result was that he gave away his possessions and began his life’s work of communicating his spiritual insights. This he did by composing poetic compositions which he sang to the accompaniment of a rabab, the stringed instrument that his Muslim travelling companion, Mardana, played. After travelling extensively Guru Nanak settled down, gathering a community of disciples (Sikhs) around him, in a place known as Kartarpur (‘Creator Town’).

Guru Nanak’s poems (or shabads) in the Guru Granth Sahib (scripture) give a clear sense of his awareness of there being one supreme reality (ik oankar) behind the world’s many phenomena. His shabads emphasize the need for integrity rather than outward displays of being religious, plus the importance of being mindful of God’s name (nam) and being generous to others through dan (pronounced like the English word ‘darn’) i.e. giving to others. His poems are rich in word-pictures of animals and birds and human activities such as farming and commerce.

Centrality of the Guru Granth Sahib

The Guru Granth Sahib is the sacred text of the Sikh community and the embodiment of the Guru. It is central to the lives of devout Sikhs, both in the sense of being physically present in the gurdwara (place of worship) and as Sikhs’ ultimate spiritual authority. Moreover, each day devout Sikhs hear or recite the scriptural passages that constitute their daily prayers and the Guru Granth Sahib also plays an integral part in life cycle rites and festivals.

As the Granth Sahib is Sikhs’ spiritual teacher, their Guru, it is honored as a sovereign used to be, centuries ago in India. The 1430-page volume is enthroned under a canopy and it reposes on cushions on the palki (literally palanquin i.e. the special stand). An attendant waves a chauri above it when it is open and being read: the chauri is a fan consisting of yak tail hair set in a wooden handle. When not being read, the volume is covered by red and gold cloths known as rumalas, and in many gurdwaras, after the late evening prayer, it is ceremonially carried to a special bedroom where it is laid to rest.

Those Sikhs who keep the Guru Granth Sahib at home honor it in a room of its own. If a copy is temporarily housed in a Sikh’s home for the duration of a path (reading of the entire volume) strict rules are observed – for example no non-vegetarian food is kept or cooked. In other words, the house is temporarily a gurdwara.

Sikhs believe that all ten human Gurus embodied the same spirit of Guruship and that their different styles were appropriate to the differing circumstances in which they lived. Guru Nanak’s first four successors, Guru Angad Dev, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das and Guru Arjan Dev, were also poets. Their compositions, together with Guru Nanak’s, became the basis of the Guru Granth Sahib. While their spiritual emphasis seamlessly continued Guru Nanak’s, each made a distinctive contribution to Sikh community life. Guru Angad formalized the Gurmukhi script in which the scripture is written. It was almost certainly developed from the shorthand that accountants used for keeping their accounts, as a simpler version of the script that is still used for the older language of Sanskrit.

Sikhs turn to the Guru Granth Sahib for guidance when they face a dilemma. The time-honored method is for the volume to be opened at random and for the words of the hymn at the top of the left-hand page to be taken as the Guru’s response. This guidance is called a vak. A vak is taken each day in all gurdwaras and the words are displayed for everyone to read.

Sikh Worship

Sikhs worship in Gurdwaras.

A gurdwara is a building in which Sikhs gather for congregational worship. However, wherever the Guru Granth Sahib is installed is a sacred place for Sikhs, whether this is a room in a private house or a gurdwara. The word is often translated as ‘doorway to the Guru’ and it means the place in which the Guru, embodied in the Guru Granth Sahib, is resident and honoured. In the 18th and 19th centuries the word gurdwara gradually replaced the earlier term ‘dharamsala’ for rooms used for religious purposes during the Gurus’ lifetimes.

There are gurdwaras in every country where Sikh communities have settled. In the UK alone there are probably about 300 gurdwaras. In the early years of Sikh settlement in the UK, rented premises served as gurdwaras. The next stage was to purchase a building and modify it for Sikh worship. An increasing number of gurdwaras are purpose-built, with architectural features inspired by historic gurdwaras in India.

In a gurdwara both men and women must wear a head covering to show their respect for the Guru Granth Sahib and footwear must be removed on entering the building. No tobacco or non-vegetarian food is allowed inside and no-one may enter under the influence of alcohol. In the worship hall it is respectful to bow before the enthroned Guru Granth Sahib and then sit on the floor, cross-legged and facing the Guru Granth Sahib.

Most of the Sikh historic gurdwaras are in north India though some are in Pakistan. (In the Gurus’ time, and until 1947, the Punjab region was not bisected by a national frontier, as Pakistan had not been created.) The architecture of major historic gurdwaras, involving fluted cupolas (gumbads), is influenced by Mughal style. Famous gurdwaras in Pakistan commemorate Guru Nanak’s life: in Nankana Sahib a gurdwara marks the place where he was born and at Kartarpur Sahib a gurdwara stands where he founded a settlement and (in 1539) passed away. Equally well-known is Panja Sahib gurdwara in Hasan Abdal (about 40 kilometres north-west of Islamabad), where a rock bears what is believed to be the imprint of Guru Nanak’s hand.

The title ‘sahib’ in the names of cities (e.g. Anandpur Sahib) and major gurdwaras expresses Sikhs’ reverence for locations associated with their Gurus’ lives.

Five notable gurdwaras in India are known as takhts: takht means throne or seat of authority.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/lIHJcTf31NM?si=JQW3FV4hbhXoYvmS

World Religions: the Spirit Searching Copyright © 2021 by Jody L Ondich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

LITERATURE

Tukaram’s Selected Poems

Composed ca. 1621-1649 C.E.

Translated by Nicol Macnicol; licensed public domain

Tukaram is a Marathi poet, born near Pune, India, who is often regarded as the greatest writer in the Marathi language. Tukaram was devoted to the Hindu god Vitthala, a local incarnation of Visnu, a principal Hindu deity that has ten avatars or incarnations. He was part of the bhakti movement that promoted the idea that moksha (or liberation) is attainable by anyone, and he came into conflict with the local Brahmins (the highest Hindu caste of priesthood) because he challenged caste hierarchy in Hindu religious practices. In the areas of Maharashtra (the western region of India), he is regarded as the most important poetic and spiritual figure; for this, he is also called “Sant Tukaram,” the epithet “Sant” noting his saintly quality. The canon of Tukaram’s poetry contains about 4600 abhangas (short “unbroken” hymns), which are among the most famous Indian poems. These poems are designed to be sung and performed with musical instruments. J. Nelson Fraser and K. B. Marathe translated his poems into English; they were published in 1909-15 and reprinted in 1981.

The Mother’s House

As the bride looks back to her mother’s house,

And goes, but with dragging feet;

So my soul looks up unto thee and longs,

That thou and I may meet.

As a child cries out and is sore distressed,

When its mother it cannot see,

As a fish that is taken from out the wave,

So ‘tis, says Tuka, with me.

The Suppliant

How can I know the right,—

So helpless I—

Since thou thy face hast hid from me,

O thou most high!

I call and call again

At thy high gate.

None hears me; empty is the house

And desolate.

If but before thy door

A guest appear,

Thou’lt speak to him some fitting word,

Some word of cheer.

Such courtesy, O Lord,

Becometh thee,

And we,—ah, we’re not lost to sense

So utterly.

A Beggar For Love

A beggar at thy door,

Pleading I stand;

Give me an alms, O God,

Love from thy loving hand.

Spare me the barren task,

To come, and come for nought.

A gift poor Tuka craves,

Unmerited, unbought.

God Who Is Our Home

To the child how dull the Fair

If his mother be not there!

So my heart apart from thee,

O thou Lord of Pandharl I

Chatak turns from stream and lake,

Only rain his thirst can slake.

How the lotus all the night

Dreameth, dreameth of the light!

As the stream to fishes thou,

As is to the calf the cow.

To a faithful wife how dear

Tidings of her Lord to hear!

How a miser’s heart is set

On the wealth he hopes to get!

Such, says Tuka, such am I!

But for thee I’d surely die.

Copyright: World Literature I: Beginnings to 1650 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

ARCHITECTURE

Meeknashi Temple

Many sacred sites and structures in India have mythical origins, and the city of Madurai near the southern tip of the subcontinent in Tamil Nadu state is no exception. According to tradition, more than 3500 years ago the god Indra installed a small tower over a naturally formed stone lingam as a sign of devotion to Shiva, one of the primary deities in the vast Hindu pantheon. (Typically considered the god of destruction, Shiva’s characteristics also include creation and virility.) Other gods followed Indra’s lead and began to worship there. Soon a human devotee witnessed the miraculous scene of gods worshipping at the lingam and notified the local king, Kulashekhara Pandya, who built a temple at the site.

The story of the figure of Meenakshi is also legendary. It describes a Pandya king, Malayadhvaja, who hoped for a son and heir. He carefully performed a fire ceremony requesting that the gods fulfill this wish. Instead, he was granted a daughter, Meenakshi, who was born with three breasts. The gods told the king not to worry, but to raise Meenakshi as a brave warrior, just as he would a son, and that when she grew up and met her true love, her third breast would disappear. Meenakshi proved herself gifted in battle, conquering armies in all directions. When she sought to attack the north, however, she was confronted by the god Shiva, who dwells on Mount Kailasha, deep in the Himalayas. Upon seeing him, one of her breasts fell off and the prophecy was realized. Another principal god in the Hindu pantheon, Vishnu (in the guise of Meenakshi’s brother), presided over the wedding of Shiva and Meenakshi, and the divine couple made their home in Madurai, where they ruled (and continue to symbolically rule) as queen and king.

Temple complex plan

The earliest temple at Madurai was likely constructed in the seventh century C.E., but the temple complex we experience today is largely the work of the Nayak dynasty in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They enlarged the complex and redesigned the surrounding streets in accordance with the sacred tradition of the Vastu Shastra (Hindu texts prescribing the form, proportions, measurements, ground plan, and layout of architecture).

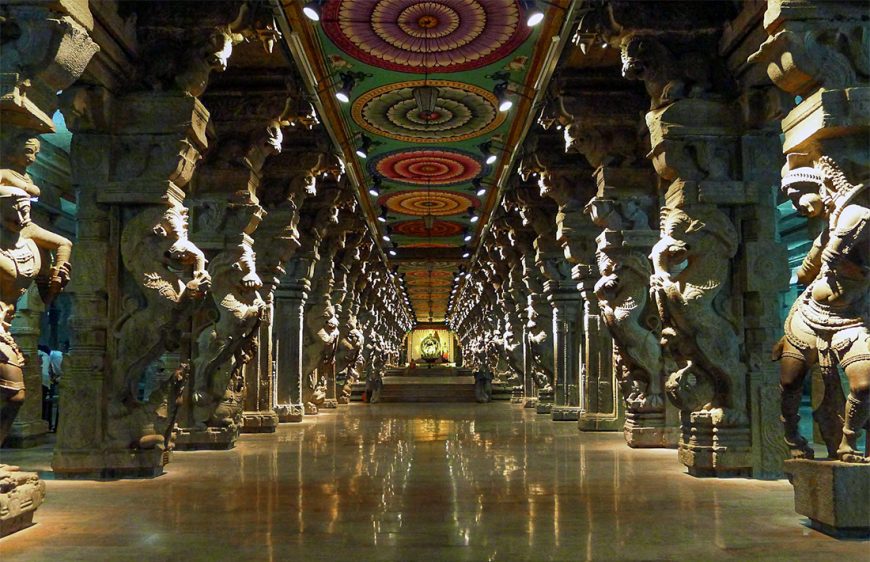

The Meenakshi Temple is a prime example of Dravidian architecture—a style of Hindu architecture common in the southern states of India. Characteristics of Dravidian architecture often include covered porches on temples, tall entry gate towers on two or more sides, many-pillared halls, and a water tank or reservoir for ritual bathing.

Two principal sanctuaries (accessible only by Hindus) sit at the center of the temple complex: one dedicated to Meenakshi (who is considered a manifestation of the goddess Parvati), and another dedicated to Sundareshwara or “Beautiful Lord” (a form of the god Shiva). A gold finial, visible only from a high vantage point, caps each of these sanctuaries. Fronting each sanctuary is a mandapa (a pillared, porch-like structure) that pilgrims pass through as they make their way to the garbagriha (the innermost sacred areas of the sanctuary).

Each Friday evening, sculpted figures of Meenakshi and Sundareshwara are placed upon a swing in the temple and gently rocked in imitation of a romantic interlude, and each spring they are celebrated in a massive multi-day festival.

At the south end of the complex is the Golden Lily Tank, which is used by believers for ritual bathing before they enter the sanctuaries of Meenakshi and Sundareshwara. The northeast corner of the complex is occupied by the Thousand Pillar Hall, a vast, ornate mandapa. Although there are actually only 985 pillars, the effect is impressive, with most of the stone pillars carved in high or low relief depicting gods, demons, and divine animals. Originally this space was likely used for religious dancing and musical performances as well as a place to gain an audience with the king. Today the Thousand Pillar Hall functions primarily as a museum, with exhibitions of bronze sculptures, paintings, and objects from the temple’s history.

The Gopuras

Some visitors to the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai mistake the gopuras for the sacred temples and shrines themselves. The word gopura may be derived from the Tamil words ko meaning “king,” and puram meaning “exterior or gateway”; or from the Sanskrit go meaning “cow” and puram meaning “town.” Here, there are fourteen gopuras roughly oriented to the cardinal directions and flanking either the temple of Meenakshi or Sundareshwara, or the entire walled compound. They generally increase in height as one moves further away from the center of the complex, as the outermost sections were continually added to by a succession of rulers, who commissioned ever grander towers as a sign of their power and devotion. The gopuras act as symbolic markers for the sacred space into which they lead and most are covered with a profusion of brightly painted stucco figures representing gods and demons.

The tallest gopura rises to approximately 170 feet and contains more than 1500 figures that are repaired and repainted every twelve years. This multitude of brightly-colored figures excites some visitors and repels others. It is likely that most Hindu temples (just like their ancient Greek and Egyptian counterparts) were painted in vibrant hues, and many are still today.

Copyright: Edward Fosmire, “The Meenakshi Temple at Madurai,” in Smarthistory, April 3, 2018, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/meenakshi-madurai/.

Taj Mahal

Shah Jahan was the fifth ruler of the Mughal dynasty. During the third year of his reign, his favorite wife (known as Mumtaz Mahal), died due to complications arising from the birth of their fourteenth child. Deeply saddened, the emperor started planning the construction of a suitable, permanent resting place for his beloved wife almost immediately. The result of his efforts and resources was the creation of what was called the Luminous Tomb in contemporary Mughal texts and is what the world knows today as the Taj Mahal.

In general terms, Sunni Muslims favor a simple burial, under an open sky. But notable domed mausolea for Mughals (as well as for other Central Asian rulers) were built prior to Shah Jahan’s rule, so in this regard, the Taj is not unique. The Taj is, however, exceptional for its monumental scale, stunning gardens, lavish ornamentation, and its overt use of white marble. Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal in Agra, where he took the throne in 1628. First conquered by Muslim invaders in the eleventh century, the city had been transformed into a flourishing area of trade during Shah Jahan’s rule. Situated on the banks of the Yamuna River allowed for easy access to water, and Agra soon earned the reputation as a “riverfront garden city,” on account of its meticulously planned gardens, lush with flowering bushes and fruit-bearing trees in the sixteenth century.

Paradise on Earth

Entry to the Taj Mahal complex via the forecourt, which in the sixteenth century housed shops, and through a monumental gate of inlaid and highly decorated red sandstone made for a first impression of grand splendor and symmetry: aligned along a long water channel through this gate is the Taj—set majestically on a raised platform on the north end. The rectangular complex runs roughly 1860 feet on the north-south axis, and 1000 feet on the east-west axis.

The white-marble mausoleum is flanked on either side by identical buildings in red sandstone. One of these serves as a mosque, and the other, whose exact function is unknown, provides architectural balance.

The marble structure is topped by a bulbous dome and surrounded by four minarets of equal height. While minarets in Islamic architecture are usually associated with mosques—for use by the muezzin who leads the call to prayer—here, they are not functional, but ornamental, once again underscoring the Mughal focus on structural balance and harmony.

The interior floor plan of the Taj exhibits the hasht bishisht (eight levels) principle, alluding to the eight levels of paradise. Consisting of eight halls and side rooms connected to the main space in a cross-axial plan—the favored design for Islamic architecture from the mid-fifteenth century—the center of the main chamber holds Mumtaz Mahal’s intricately decorated marble cenotaph on a raised platform. The emperor’s cenotaph was laid down beside hers after he died three decades later—both are encased in an octagon of exquisitely carved white-marble screens. The coffins bearing their remains lie in the spaces directly beneath the cenotaphs.

Qur’anic verses inscribed into the walls of the building and designs inlaid with semi-precious stones—coral, onyx, carnelian, amethyst, and lapis lazuli—add to the splendor of the Taj’s white exterior. The dominant theme of the carved imagery is floral, showing some recognizable, and other fanciful species of flowers—another link to the theme of paradise

Some of the Taj Mahal’s architecture fuses aspects from other Islamic traditions, but other aspects reflect with indigenous style elements. In particular, this is evident in the umbrella-shaped ornamental chhatris (dome shaped pavillions) atop the pavilions and minarets.

And whereas most Mughal-era buildings tended to use red stone for exteriors and functional architecture (such as military buildings and forts)—reserving white marble for special inner spaces or for the tombs of holy men, the Taj’s entire main structure is constructed of white marble and the auxiliary buildings are composed of red sandstone. This white-and-red color scheme of the built complex may correspond with principles laid down in ancient Hindu texts—in which white stood for purity and the priestly class, and red represented the color of the warrior class.

The gardens

Stretching in front of the Taj Mahal is a monumental char bagh garden. Typically, a char bagh was divided into four main quadrants, with a building (such as a pavilion or tomb) along its central axis. When viewed from the main gateway today, the Taj Mahal appears to deviate from this norm, as it is not centrally placed within the garden, but rather located at the end of a complex that is backed by the river, such as was found in other Mughal-era pleasure gardens.

When viewed from the Mahtab Bagh, moonlight gardens, across the river, however, the monument appears to be centrally located in a grander complex than originally thought. This view, only possible when one incorporates the Yamuna River into the complex, speaks to the brilliance of the architect. Moreover, by raising the Taj onto an elevated foundation, the builders ensured that Shah Jahan’s funerary complex as well as the tombs of other Mughal nobles along with their attached gardens could be viewed from many angles along the river.

The garden incorporated waterways and fountains. This was a new type of gardening that was introduced to India by Babur, Shah Jahan’s great great grandfather in the sixteenth century. Given the passage of time and the intervention of many individuals in the garden since its construction, it is hard to determine the original planting and layout scheme of the garden beds at the Taj.

From the outset, the Taj was conceived of as a building that would be remembered for its magnificence for ages to come, and to that end, the best material and skills were employed. The finest marble came from quarries 250 miles away in Makrarna, Rajasthan. Mir Abd Al-Karim was designated as the lead architect. Abdul Haqq was chosen as the calligrapher, and Ustad Ahmad Lahauri was made the supervisor. Shah Jahan made sure that the principles of Mughal architecture were incorporated into the design throughout the building process.

What the Taj Mahal represents

When Mumtaz Mahal died at age 38 in 1631, the emperor is reported to have refused to engage in court festivities, postponed two of his sons’ weddings, and allegedly made frequent visits to his wife’s temporary resting place (in Burhanpur) during the time it took for the building of the Taj to be completed. Stories like these have led to the Taj Mahal being referred to as an architectural “symbol of love” in popular literature. But there are other theories: one suggests that the Taj is not a funeral monument, and that Shah Jahan might have built a similar structure even if his wife had not died. Based on the metaphoric specificity of Qur’anic and other inscriptions and the emperor’s love of thrones, another theory maintains that the Taj Mahal is a symbolic representation of a Divine Throne—the seat of God—on the Day of Judgment. A third view holds that the monument was built to represent a replica of a house of paradise. In the “paradisiacal mansion” theory, the Taj was something of a vanity project, built to glorify Mughal rule and the emperor himself.

If his accession to the throne was smooth, Shah Jahan’s departure from it was not. The emperor died not as a ruler, but as a prisoner. Relegated to Agra Fort under house arrest for eight years prior to his death in 1666, Shah Jahan could enjoy only a distant view of the Taj Mahal. But the resplendent marble mausoleum he built “with posterity in mind” endures, more than 350 years after it was constructed, and is believed to be the most recognizable sight in the world today. Laid to rest beside his beloved wife in the Taj Mahal, the man once called Padshah—King of the World—enjoys enduring fame, too, for having commissioned the world’s most extravagant and memorable mausoleum.

Copyright: Roshna Kapadia, “The Taj Mahal,” in Smarthistory, January 26, 2018, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-taj-mahal-2/.

PERFORMING ARTS

VISUAL ARTS

Art of the Mughal Empire

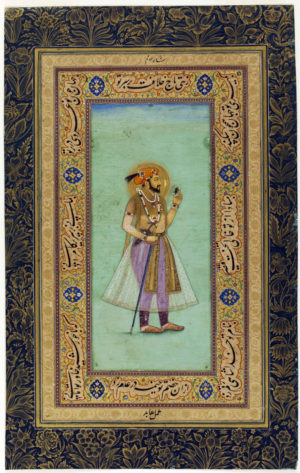

The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan stands against a plain, mint-green background dressed in a gossamer-thin tunic, his head encircled by a golden halo. A bejeweled dagger is tucked into the sash tied around his waist, and he wears a treasury of gems set in his ears and on his turban, wrapped around his upper arms, circling his wrists, and suspended in the long strands of his necklaces. Amidst all of this finery, however, there is one item that stands out: the sizeable emerald Shah Jahan grasps in his left hand, secured in a gold setting and encircled by pearls. This, we might speculate, is the very emerald that he captured during an important military campaign that he led as a prince, one of the many treasures he plundered from the sultan of Bijapur in central India. On his return to the Mughal court, Shah Jahan presented the emerald to his father, the emperor Jahangir, as a show of his fealty.

Possession of the magnificent gem would have reverted to Shah Jahan once he took the throne, however, and it was apparently meaningful enough to him for it to be included in his accession portrait, made at the time he took the throne in 1628. This painting would have been made not only to mark the historic occasion but would have been one of many intended to capture different aspects of his Shah Jahan’s authority. The particular imagery of this portrait, for instance, would have been selected as to remind viewers of his already distinguished career on the battlefield.

Interestingly, of all the treasures Shah Jahan captured from Bijapur, including particularly large diamonds and rubies, it is notable that the emerald is featured in this portrait. Here, the emerald not only represents wealth, and Shah Jahan’s defeat of a rival, but also the Mughals’ desire for precious objects from around the world, and their ability to obtain such foreign luxuries on the global trade markets that were then expanding in many novel directions.

A magnificent gem

Prior to the 1500s and the advent of the global trade involving the Americas, emeralds were only available in limited numbers from sources in Egypt, Austria, and Pakistan. However, sources in South America, particularly Colombia, provided gems of higher quality and in greater quantity, although prior to the European invasions, they only circulated within the immediate area of the mines. But as the Spanish colonists in Colombia started their own mining operations, emeralds were extracted in greater numbers and began to travel further afield, reaching Europe and Asia through a variety of sea and land networks.

The impact of this trade at the Mughal court is apparent in the expanded prominence of emeralds in writings, in paintings, and in surviving objects from the late sixteenth century on. A chronicler of the reign of Emperor Akbar, for instance, recorded emeralds as one of the major holdings in the Mughal treasury, along with the kind of gems that long been collected there, such as spinels, pearls, diamonds, sapphires, and rubies.

In the records of the reigns of Akbar’s son Jahangir and grandson Shah Jahan, there are frequent mentions of the presentation of emeralds or emerald jewelry, commissioned by the emperors as gifts to their sons and subordinates at key moments such as their birthdays, military deployments, or new governorships. In addition, European visitors to court mention that the emperors wore emerald jewelry and displayed emerald-encrusted objects during public ceremonies. In 1611, the Englishman John Jourdain describes a procession of elephants with trappings inlaid with emeralds, while in 1616, English ambassador Thomas Roe speaks of a cup, cover, and dish used by Jahangir, set with turquoises, rubies, and emeralds. In imperial portraits emerald jewelry became more noticeable as well, as demonstrated by the likeness of Shah Jahan discussed above, in which he wears emeralds mounted in necklaces and turban ornaments.

Surviving emerald objects are also plentiful. While many stones were never cut and were stored loose, there are dozens of carved beads and pendants that would have been strung with pearls and rubies to create the necklaces that appear in so many Mughal paintings. There are also a number of flat plaques decorated with floral motifs that would have been set in armbands and bracelets. Finally, there is a set of small cups whose bowls are made from solid emeralds, along with a box made of emerald plaques set into a gold lid and base.

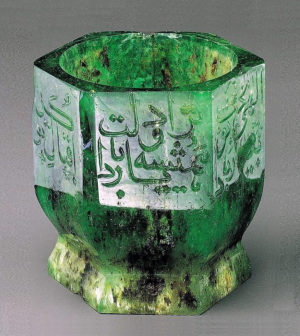

Mughal court inscriptions

But most intriguing are three emeralds that were inscribed by Jahangir with his name and titles, for this indicates that the emerald itself was of special significance in the Mughal iconography of state. These three emeralds are impressive in size, with the largest, now in the Museum of the Islamic Art, Doha weighing in at 98.74 carats. All three include the phrase Jahangir shah-i Akbar shah (King Jahangir, son of King Akbar), and two include a date of 1018 in the Islamic calendar (converting to 1609–10 C.E.). The third also included a date but it is no longer legible.

![Emerald inscribed "Jahangir Shah-i Akbar Shah 1018 [1609–10 C.E.]," India, Mughal, 3.4 x 2.8 cm, 98.74 carats (Museum of Islamic Art, Doha)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/emerald-with-inscription-300x271.jpg)

This practice can be contextualized by looking to other types of objects that the Mughals emperors inscribed, for they added their names to a range of precious items and historical objects that they collected for their personal treasuries. This includes rare and valuable porcelains acquired from China, and imperial manuscripts sourced from Iran. Most relevant to the example of the emeralds, though, would be other gemstones, specifically spinels (such as the Carew spinel above) and jades. On the one hand these stones were considered aesthetically striking and could be made into jewelry or precious objects to be used and displayed at court. These stones also had great monetary value and unblemished and high-quality specimens were hard to come by; like monarchs the world over, the Mughals sought them as an expression of their wealth. But in addition, these particular stones were desirable because they had special significance for the Mughal family line. Spinels come from a region in Afghanistan once ruled by the conqueror Timur, one of the great forebears of the Mughal line, and Timur and his descendants had also collected and inscribed them.

If this helps us to understand the Mughal practice of inscribing objects with names and titles, there is one aspect of the emeralds that diverges from the earlier examples: the fact that the emeralds did not have the same ancestral connection, having come from Colombia. Therefore, we imagine that the emeralds’ appeal was quite different in nature, and one avenue for understanding the value of emeralds to the Mughals is the extensive Persian-language literature on gems. One treatise, in circulation at the Mughal court, entitled Javahirnama (“Treatise on Precious Stones”) lists the numerous benefits of emeralds: it was considered an antidote for poisoning, it was believed to strengthen the heart, and it was thought to be useful against ailments of the stomach and liver as well as epilepsy. Therefore, the text states, the children of a ruler often wear emeralds. This may be why emeralds were gifted at significant court events, especially when princes were given new assignments.

Copyright: Dr. Marika Sardar, “Shah Jahan’s portrait, emeralds, and the exotic at the Mughal court,” in Smarthistory, October 7, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/shah-jahan-portrait-emeralds-exotic-mughal-court/.

Color in Mughal Painting

Video URL: https://youtu.be/WO9IkkjQhso?si=zC6nQKj48lorvq-k

Copyright: The J. Paul Getty Museum, “Exploring Color in Mughal Paintings,” in Smarthistory, January 29, 2020, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/color-mughal-paintings/.

Christian Art

Seated on a tiered landscape, with eyes closed in sleep, the Christ Child ponders his eventual role on earth, as sacrifice for the sins of humans. Standing on a crescent moon with hands clasped at her chest, the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception gazes towards the viewer. These two statuettes are examples of a large number of ivory figural types created in Goa and Sri Lanka during the time of Portuguese rule that began in the 16th century. For this reason, these small sculptures are often referred to as Indo-Portuguese in scholarship and by museums.

Christian Art in India

The arrival of Vasco da Gama’s fleet to Calicut in 1498 marked the beginning of Portuguese evangelization in the lands along the Malabar (southwestern) Coast of India. The Portuguese saw themselves as promoting and spreading Christian ideas and values, part of a global Catholic missionary enterprise that sought to convert non-Christians to the faith.

By the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese had established themselves in Goa, a small state on the western coast of India, with the goals of dominating the spice trade and promoting the Christian faith. Various Christian religious orders came to Goa at this time to begin the process of converting the mostly Hindu population of Goa. For the mission enterprise, churches were constructed, and small, portable images of the Catholic divine were carved in ivory and wood. Larger wooden sculptures depicting Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and Catholic saints were also created to adorn the interior of the churches. These sacred spaces and divine figures would serve to shelter, teach, and convert the population of Goa to Christianity.

In Old Goa, the former capital of Portuguese India, there are numerous churches that reflect European influence, such as the Sé Cathedral and the Church of Bom Jesus, with the former composed of a nave and side aisles of equal height. These churches recall those in Lisbon, with images of the Christian divine adorning the main altar and side altars. A wooden sculpture of Saint Francis Xavier (not shown here), for instance, is found in the Church of Bom Jesus.

Small, portable images included, for example, figurines carved in ivory, ranging from several inches to over a foot in height. These statuettes could serve as devotional objects on church altars in Goa and private altars in Goan homes, and within churches and homes abroad. Several thousand statuettes in various sizes were carved by Indian artisans under the direction of the religious orders, most notably the Jesuits (a Christian religious order founded in 1540). The Jesuits had a special interest in understanding the cultures they encountered worldwide, and they worked directly with indigenous artists to support their missionary work. As art historian Gauvin Alexander Bailey describes, Jesuit art commissions “were . . . a partnership in which the artists’ own interpretations of sacred art were encouraged and fostered.”

The Jesuits brought small paintings, prints, and sculptures from Europe for the Indian sculptors to use as models for creating artworks for their missionary enterprise. Prints were the most common European model used in the Goan workshops, due to their low cost and easy transport

In addition to these European models, Goan artisans drew from their own traditions for fashioning images of the divine and architectural forms, as well as their knowledge of sculpting. Round faces and smooth skin, for example, are features set down in the Shilpashastras, ancient texts that address the production of sculpture. Through these influences, the sculptors created works that often exhibit a synthesis of cultural traditions.

Devotional objects made whole

Indo-Portuguese ivory statuettes, many of which are now found in museum and private collections, are often incomplete and fragmentary in nature. Single figures, such as the Good Shepherd Rockery, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, and the Madonna of the Immaculate Conception from The Walters Art Museum collection all shown above, are typically all that remain of a once more vibrant, complete devotional object. A base of stylized acanthus leaves or other sculptural forms are missing from most works. Halos, crowns, and staffs made of silver as well as ivory shepherd crooks and flowering tree branches at the sides of the rockeries are now commonly lost to time, though some were also repurposed. Finally, many of these statuettes would have had painted details to accentuate facial features and garments. Others would have been fully painted.

These losses are understood through the few surviving examples that are mostly complete and through the remnants of color in the nooks and crannies of the works.

The Mount of the Good Shepherd from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is one of the more spectacular examples of a mostly complete rockery. In this work, the additional ivory pieces are still attached, depicting a flowering tree that surrounds the mount and the figure. With the decorated base of lambs, the full flowering tree surrounding Jesus, and the crooked shepherd’s staff in its rightful place, this rockery is a vision to behold. These accoutrements, along with color, add significance to the image, creating a more complete “picture” of the divine figure. They also provide iconographic details for understanding the intended messages of the piece, which were used for teaching purposes and devotional practice. The possibility of additional parts is important to keep in mind when examining these works of art.

Indo-Portuguese ivories exhibit the coming together of cultures, and the Good Shepherd Rockery figural type perfectly encapsulates how Goan sculptors created images of the divine that are at once Catholic, European, and South Asian.

Copyright: Dr. Marsha G. Olson , “Christian art in India: Indo-Portuguese ivory statuettes,” in Smarthistory, August 29, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/indo-portuguese-ivory-statuettes/.

British East India Company Art

Beginning in the seventeenth century, groups of merchants in different European countries pooled their resources to form East India Companies to increase the opportunities for lucrative trade with countries in Asia. In eighteenth-century India, these mercantile relationships turned into political and military ones. In the wake of the Battle of Plassey in 1757, for instance, the British East India Company gained the rights to collect taxes in the northeast state of Bengal, which led to their governance of the region and their negotiations with other Indian rulers to increase their power over the subcontinent. Over the next century, the British East India Company (in shorthand, the “Company”) asserted colonial control over much of India until 1858, when in the wake of a major Indian rebellion against their policies, the British crown took over rule until India regained independence in 1947.

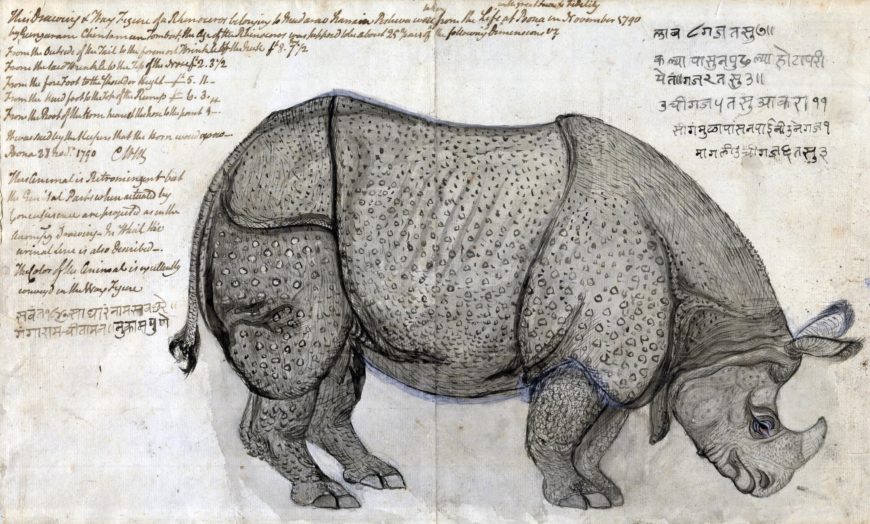

In this period, Company officials hired Indian artists to document their experiences, who have come to be known as “Company” painters as a result. Some of these artists even created images of artists working on Company commissions, such as Gangaram Tambat who depicted four artists using an optical device to draw a series of temples on a hill in the western Indian city of Poona (Pune) in 1795. [1] Gangaram worked for the Company official Charles Warre Malet, who was in Poona as a type of ambassador or “Resident” to the court of the Maratha rulers, a military elite who rose to power in western India in the late seventeenth century and expanded their territories across western and central India over the eighteenth century. Malet’s brief was to negotiate a treaty with the Marathas against their mutual enemy, Tipu Sultan of Mysore, to the south; however, he also sought other types of information related to the rulers with whom he sought to ally.

Gangaram’s drawings are sketchy, conveying a sense of immediacy balanced by clarity and precision. They include his signature, the date, and inscriptions by him and Malet in multiple languages. They offer a lens into how Indian artists learned European techniques and attended to subjects of interest to Company officials. View of Parbati (Parvati) portrays regional architecture and the surrounding landscape in conventions familiar to a European viewer. For example, Gangaram used one-point perspective to render the distant hill, added shadows to the figures and hillside to build three dimensions, and framed the image with large trees and a blue sky in a “picturesque” manner even as he stressed the “scientific” rendering of the structures via the viewing device.

Gangaram applied European techniques to other subjects he produced for Malet, including animals in the Maratha court’s menagerie, such as a rhinoceros, a series of wrestlers (jeyties) exercising, a group of Hindu devotees (not shown), figures intimate with Malet, including his Indian mistress, Bibi Amber Kaur, and their children (not shown). He also used European techniques for architecture, such as for the famed rock-carved temples of the region, as seen in an intricate façade of a Buddhist temple at Karle (known to Company officials as Ekvera in the period due to a Hindu temple dedicated to the goddess at the site), but he interpreted them with flair.

Here, Gangaram registered his patron’s desire for a perspectival, three-dimensional structure by creating a type of diorama. To his depiction of the main façade, he attached slim pieces of paper to either side via seams and shaded them a darker gray to represent the passage into the temple.

These subjects—landscape and architecture, natural history, manners and customs of the populace, and personal life—are found across paintings commissioned by Company officials and purchased by them on the commercial market. [2] They point to the ultimate aim of the Company, and of many Company officials: to understand and categorize information about the subcontinent in order to control people, goods, and lands. These colonial goals were nuanced by the specific interests of patrons and by the ingenuity of the artists they hired.

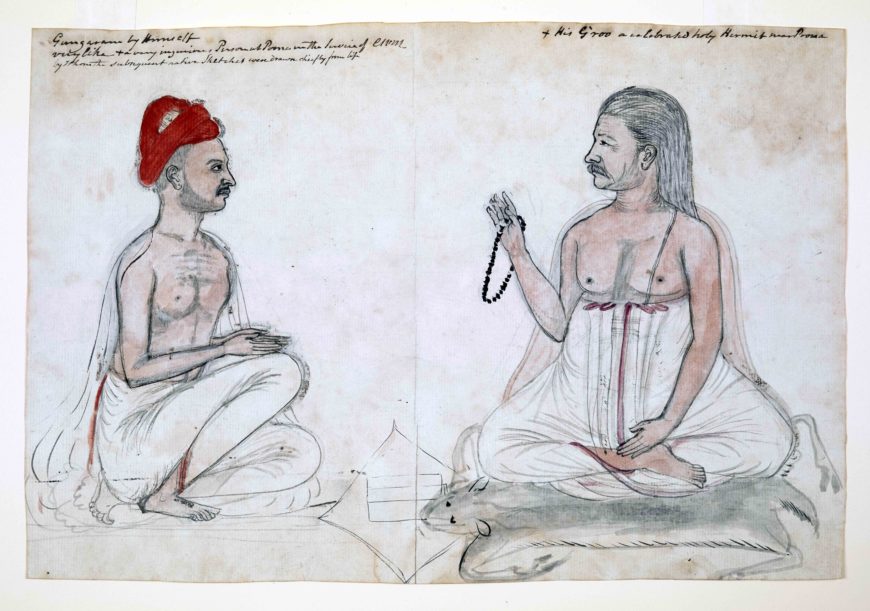

Gangaram’s drawings elucidate his work as a Company artist, but they also point to his training in a style of painting popular in western India, in which artists delineated figures through strong outlines embellished with flat planes of color, as well as his own artistic interests. For example, a sketch by Gangaram depicts the artist in a red turban seated on the ground facing his Guru (spiritual leader) with his hands clasped together in a gesture of respect. This arrangement of figures is seen in other local paintings, such as one by Shivram Chitari of a Maratha king with his minister. While Shivram’s painting is embellished with a formidable entourage inhabiting a bright and busy landscape in the tradition of courtly paintings in the region, Gangaram’s stands as a personal and informal record of the artist’s devotion. We might think of Gangaram then as a “Company” painter, a “Poona” painter, and his own painter.

Artistic agency and adaptation in Mughal Delhi

Artists across India who worked for the Company, for Indian patrons, and for the open market in this period can be described in similarly multivalent terms. [3] The Company works share an attention to certain subjects and categories, like landscape, architecture, portraiture, manners and customs, and natural history, and the adaptation of selective European artistic conventions and techniques such as perspective and shading, but these artists worked in diverse styles that reflect their artistic training and individual approaches and the patrons for whom they worked.

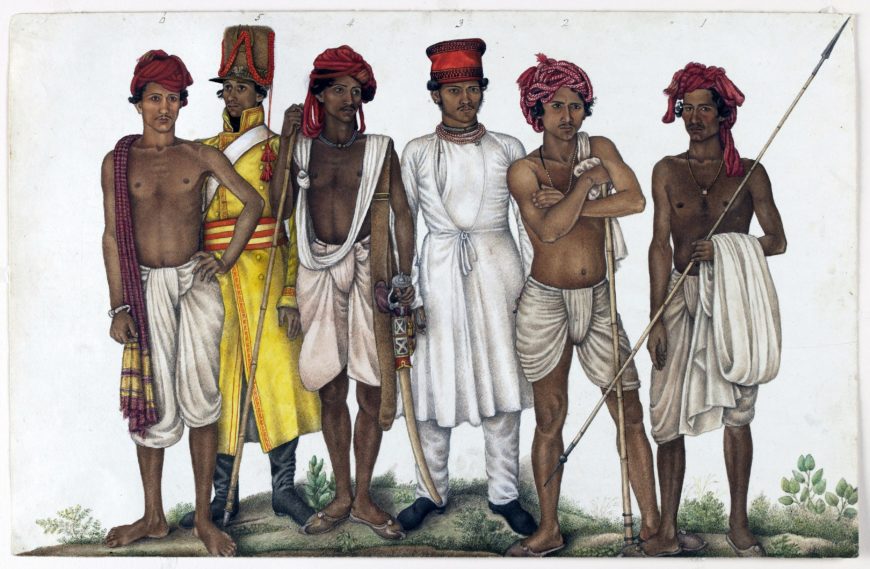

In Delhi, artists trained to render their paintings in fine brushwork on burnished paper in the painting techniques of the Mughal empire (1526–1858) poignantly portrayed figures related to their Company patrons’ governance and military units. For example, in an album for William Fraser, Ghulam ‘Ali Khan (or another artist in his family) portrayed six recruits. [4] He carefully rendered the men’s faces, bodies and dress through tone and shadows to detail their forms and penetrating gazes.

This ability to call forth the presence of a person in a portrait was a honed skill at the Mughal court. However, the collection of these men—facing forward in comparison to the preferred profile or three-quarter view of the Mughals—on a bare background is more to the taste of the Company.

Colonial knowledge in paint in Calcutta, Patna, Tanjore, and the Deccan

Works like the drawing of a Mughal Tomb classified information at the same time as they marveled at the sources. These images participated in artists’ and Company officials’ collection of colonial knowledge across the subcontinent; they projected the continuity of past empires with their own, highlighted the value of colonial goods and possessions, and provided information about the people whom they wished to control. Another artist, Sheikh Zain al-Din, and others in his artistic circle in Calcutta (now Kolkata), produced hundreds of highly detailed paintings of flora and fauna, such as of an Indian roller on a sandalwood branch, for Lady Mary Impey and other Company patrons’ natural history projects. [7]

In Patna, artists such as Shiva Lal and Shiva Dayal Lal, created series of images of trades and occupations, such as this scene of women selling vegetables and grain, which they sold from their market shop.

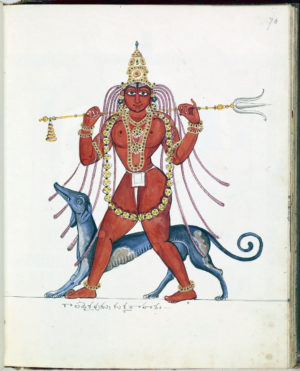

In the central Indian region of the Deccan, artists produced highly finished albums of Indian rulers from an early period; while in south India, such as in Tanjore (Thanjavur), they made albums of deities, such as the Hindu god Bhairava, among other subjects. [8]

These artists produced series of images that defined Indian subjects for their Company patrons and the wider market. They share an interest in natural history, people, or gods, for instance, while they also differ according to their region of production and the particularity of the artists or patrons involved.

Indian artists who worked for Company patrons attended to certain categories and adapted European artistic conventions and techniques, which is why they have been called Company painters in scholarship. However, these same artists also worked for Indian patrons and the commercial market; they were skilled in multiple modes of production, including those of their own invention. Their diverse skillsets puts pressure on the term Company painter as the sole definition of an individual artist, one that is ethnically and hierarchically based. Rather, “Company” painting should be used as a stylistic term, a method to identify how artists from a range of backgrounds produced art for patrons connected to East India Companies or the wider market. These arts can be identified through certain European techniques and an attention to certain subject matters, but also differentiated by the diversity of their production. These artists developed the Company style alongside others in seventeenth- to nineteenth-century India that both shaped the Company’s understanding of India and was shaped by these artists’ knowledge.