38 EASTERN ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

China

By cutting off access to foreign trade outside the tribute system, the Ming government greatly reduced its tax revenue, which left it constantly short of funds. To reduce the cost of government, Hongwu made wealthier peasant families responsible for collecting taxes and maintaining order in their villages, saving the expense of paying officials to do so. Soldiers’ families were given land to farm in order to make the army self-supporting. High taxes were imposed on merchants and scholarly elites. These reforms were largely unsuccessful. Soldiers often could not raise enough food to support themselves and either sold the land they had been given or deserted. Even wealthy peasants could not always afford to provide the services the government expected of them. Local officials lacked necessary funds, and they began to impose additional fees on peasants.

Hongwu’s son, the Yongle emperor, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty, was a bit more curious about the world outside China and more desirous of tribute than his father. Between 1405 and 1421, he dispatched Zheng He, a trusted palace eunuch, on a series of six voyages throughout the Indian Ocean. The purpose of these voyages was to demonstrate the wealth and power of China by distributing gifts to foreign rulers, thus prompting them to pledge themselves as vassals and offer tribute to the Ming emperor.

The first fleet departed in 1405. It consisted of 317 ships and 27,000 people, including sailors, soldiers, scholars, craftspeople, and fortune-tellers. It rode the monsoon winds from the coast of Fujian in southeast China to the Kingdom of Champa in southern Vietnam, where the crew traded silks and porcelain for lacquer wood, rhinoceros horn, and elephant ivory. The ships then visited Aceh, Majapahit, and several other city-states in Indonesia, where many Chinese merchants lived. From there, they moved on to Sri Lanka and Calicut. In Calicut, the crew traded for pearls, peppers, gems, and coral. On the return leg, Zheng He brought diplomats from the states he had visited to meet the emperor. On later voyages, the ships visited Persia, Arabia, and East Africa, and on one return trip, a ship carried a giraffe as a gift for the Ming emperor.

China continued to interest itself in the affairs of territories it bordered, however. In 1406–1407, China invaded Vietnam to restore the Tran emperor to his throne after it had been usurped. A Vietnamese revolt ended China’s occupation of the country in 1427. The victorious Lê dynasty then pledged loyalty to China as a vassal state. In 1449, a Chinese military expedition into Mongol territory ended in the slaughter of the Chinese at the Battle of Tumu. In 1592 and 1597, Ming armies helped Korean troops repel a Japanese invasion. At other times, though, the Ming attempted to avoid conflict whenever possible. After the 1449 defeat of the Chinese by western Mongols (known as the Oirat) at the Battle of Tumu, construction began on a new Great Wall to supplement the original Great Wall, the earthen fortifications erected by the Qin in the third century BCE. It was hoped that the new fortification would protect China from the outside world.

As the Ming economy grew, so too did its population. Crops from the Americas such as sweet potatoes and maize were adopted by many peasants, especially those who lived in hilly, dry regions like Sichuan. These crops grew well and provided abundant calories for farm families. Hot and sweet peppers from the Americas were added to regional cuisines, transforming them, and peanuts added not only variety but an important source of fat in diets lacking meat. These new crops ultimately proved harmful, however. As hillsides were cleared to plant corn, for example, regions became deforested and lost their valuable topsoil. Population growth was also not accompanied by an increase in cultivated land sufficient to support the added numbers of people, and in many regions, farmers found themselves tilling smaller fields as the generations passed.

New wealth led many commoners to imitate the nobility, building large homes with courtyards and gardens, purchasing fine rosewood furniture, collecting art and antiques, and hiring tutors to educate their children and prepare their sons for the examinations that would earn them jobs in the imperial bureaucracy. Restaurants, inns, and taverns sprang up in market towns and cities across the country as people became able to afford leisure activities. A flourishing printing industry produced not only agricultural manuals and copies of the Confucian classics but also plays and novels, some with erotic scenes and storylines. Guidebooks advised people traveling on business about where to stay and eat and also provided information about sites of historical interest. Increasingly, people began to travel for pleasure as well. In the cities prostitution boomed, and at the very top of a complex hierarchy, courtesans hired themselves out to wealthy merchants to entertain male guests at parties by playing music or competing with them in poetry contests.

North of the Yellow River, discontented peasants formed an army led by Li Zicheng. In the area between the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, other rebels were led by Zhang Xianzhong. Province after province erupted in violence. In April 1644, Li Zicheng’s peasant army seized Beijing. In desperation, the last Ming emperor hanged himself in the palace garden after killing most of his family. Li declared himself the ruler of China and the founder of a new dynasty. He did not rule long enough to establish his dynasty, however. The next rulers of China were the Manchus.

The Manchus were members of an ethnic group that lived northeast of the Great Wall in southern Manchuria. They were descended from Jurchen pastoralists who had established the Jin dynasty that ruled northern China from 1115 to 1234 until their defeat by the Mongols. The Manchus had then settled down and become farmers. In the late sixteenth century, the Manchu leader Nurhaci formed the Manchu tribes into a state that paid tribute to the Ming emperor. In 1616, as the Ming dynasty began to collapse, the Manchus attacked Chinese settlements on the Liaodong Peninsula. They forced artisans to provide weapons for their army and farmers to provide food. Officials and army officers who were willing to submit to them were given positions in the Manchu administration. Those who rebelled were massacred.

Following Nurhaci’s death in 1626, his son Hong Taiji proclaimed himself the leader of the Qing (“pure,” “clear”) dynasty. As he expanded Manchu control over Chinese territory, he adopted Chinese forms of administration and incorporated greater numbers of Chinese officials in his government. Chinese bureaucrats and army officers, disgusted with the corruption of the Ming government and its inability to respond to the country’s problems, began to defect to the Manchus in large numbers. Fearing ongoing chaos following Li Zicheng’s capture of Beijing, Ming general Wu Sangui, who was charged with guarding the eastern end of the Great Wall, allowed the Manchu armies through. On May 27, 1644, Wu Sangui’s troops and Manchu forces defeated Li Zicheng’s army and took control of Beijing. The Manchu armies swept south, but Ming resistance there was fierce, and it was not until 1683 that all of China was brought under Manchu control.

Despite what many Chinese had feared, the early Qing emperors proved good rulers. They strove to preserve their identity as Manchus, but they also embraced Chinese culture. The first Qing emperor, Kangxi, toured China to acquaint himself with his new domain. He adopted the Chinese bureaucratic apparatus and ordered that each of the government’s six major ministries be led by Manchu and Han Chinese co-administrators. Kangxi governed according to Confucian principles and maintained the system of imperial examinations for government jobs.

The Manchu were careful to maintain their superior positions, however, and demanded loyalty from the Chinese. For example, local positions in government were usually given to Han Chinese bureaucrats, but supervisory positions were given to Manchus. All males were also required to demonstrate their acceptance of Manchu rule by wearing the distinctive Manchu hairstyle; the front part of the head was shaved, and the hair in the back was grown long and braided into a single queue. After 1645, men who did not wear their hair in this fashion were subject to execution.

The Qing, however, continued the Ming policy of interacting with other countries as little as possible. Like the Ming, they did intervene in Asia where it seemed their interests were at stake. For example, in 1683, the island of Taiwan, a base for pirates and a refuge for fleeing Ming loyalists, was made part of China. In 1720, Qing armies took control of the city of Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. In the 1750s, they fought Mongols and Uighurs in central Asia and incorporated the province of Xinjiang (“new province”) into China.

During the Qing dynasty, China continued to rely on foreign trade income, and European demand for Chinese products did not cease. The Qing remained wary of Europeans, however, and wished to minimize contact with foreigners as the Japanese had done. Non-Chinese were allowed to reside in Macao, but after 1759 they could conduct trade only through the port of Guangzhou and trade only with the Co-hong, the official Chinese merchant guild. While in the city on business, they had to stay in a special quarter for Europeans. When they had finished their transactions, they had to depart.

In the eyes of the Chinese, Europe was an inferior place that possessed nothing of interest. Although European scientific knowledge was impressive to some, most Chinese merchants and officials maintained a disdainful attitude toward the West that was reflected in the way in which Qianlong received Lord George Macartney, who visited China in 1793 on behalf of the British king. Qianlong demanded that Macartney, as the representative of an inferior monarch, demonstrate his respect by kneeling and knocking his head on the ground, the traditional way in which vassals greeted the emperor. Macartney refused to do so, and Qianlong announced that he was willing to accept the British monarch as a vassal but did not consider him an equal. He also refused Britain’s request to establish a permanent embassy in China. China, he noted, already had everything it needed, and Britain had nothing of value to offer.

Japan

In the 1400s, Japan was locked in what seemed to be unending internal strife. The Ashikaga shoguns (military overlords) who supposedly ruled the country were too weak to prevent their vassals from fighting one another or to deal with pirate bands that attacked the coasts of Japan, Korea, and China (Figure 2.18). Powerful samurai began to style themselves daimyos (“great lords”) and ruled their territories as if they were independent kingdoms; they imposed their own laws, collected tolls from those who entered, and recruited warriors loyal only to them, instead of to the shogun or the emperor. From this period of chaos emerged a succession of three powerful samurai who came to be known as “the three unifiers.” Beginning in the 1560s, Oda Nobunaga began to unite Japan under his rule. He was succeeded by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. These men ended the incessant violence, united Japan under a strong central government, and defined the relationship their nation had with the West.

In 1543, Portuguese ships arrived in Japan. It was the logical end point of a route that had taken them around the coast of Africa, eastward through the Indian Ocean, and into the Pacific. They wished to trade. They also wished to win converts for the Roman Catholic Church, as they had done elsewhere in Asia. The Portuguese were soon followed by the Spanish in 1549, and on the heels of the Portuguese and Spanish came the Dutch and the English. These last two nations, however, were less interested in religion than in profit.

The Jesuit priests brought by the Spanish and Portuguese proved quite successful at winning souls. Those like Gaspar Vilela, who arrived in Japan in 1556, often learned the Japanese language so they could communicate directly with converts. By 1600, more than 100,000 Japanese had become Roman Catholics, and half the Jesuits serving in Japan were Japanese. Nagasaki, on the southern island of Kyushu, was the most Christianized community in Japan and had ten churches. Although most samurai were not interested in becoming Roman Catholics, they were nevertheless interested in something else the Europeans had to offer—guns. Many daimyos became Christian or offered the missionaries support in an effort to obtain weapons and gunpowder to assist them in their battles with rival samurai.

Guns had a great impact on Japanese warfare even though they were difficult to aim and slow to reload. One gun did not give its possessor an advantage in battle over opponents armed with swords, pikes, or lances. However, when soldiers massed together and groups of them fired in succession, as Europeans fought, they could easily defeat those armed with traditional Japanese weapons. Oda Nobunaga made use of this new style of fighting. In 1575, at the Battle of Nagashino, he and his vassal Tokugawa Ieyasu used companies of samurai armed with European guns to defeat the warriors of the Takeda clan. By 1582, the year he was assassinated by one of his vassals, Oda had unified the central portion of the main Japanese island of Honshu, including the area surrounding Kyoto, the seat of the emperor.

Upon Oda’s death, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a vassal of his, succeeded to his position after defeating the army of Oda’s assassin. By 1590, Hideyoshi had defeated all the daimyos in Japan and required that they declare their loyalty to him. He disarmed non-samurai and forbade peasants to leave the land or become soldiers, while also forbidding samurai to take up any occupation other than war.

Unlike Oda Nobunaga, who had been relatively unconcerned with the activities of Christians, Hideyoshi was more suspicious of them. A devout Buddhist, he disapproved of Christians’ eating of cattle and horses and was horrified by the destruction of Buddhist temples and objects of worship by some overly zealous converts, acts in which Gaspar Vilela had participated. In 1587, Hideyoshi ordered Christian missionaries to leave Japan. The edict was not enforced, but the Jesuits, alarmed, asked Christian daimyos to help them attack the shogun, which they refused to do. In 1590, the Jesuits in Japan resolved instead to refrain from intervening in Japanese affairs, but they secretly continued to provide funds for Christian daimyos.

Neither approach was completely successful in avoiding Hideyoshi’s ire. In 1596 the San Felipe, a Spanish ship sailing from the Philippines to Mexico, was caught in typhoons in the Pacific and wrecked on a sandbar in the harbor of Urado, on the Japanese island of Shikoku. The local daimyo confiscated the vessel’s cargo, which Japanese law allowed, and when the ship’s captain protested, the daimyo suggested he approach Mashita Nagamori, one of the shogun’s officials, for assistance. Accordingly, the Spanish captain sent two men to the capital of Kyoto to meet with Nagamori.

In 1592, Hideyoshi invaded Korea, a vassal state of the Ming dynasty, but Chinese troops stopped the Japanese advance. In 1597, he attacked again and was again defeated, this time by Chinese and Korean troops and Korea’s navy. In 1598 he died, leaving his five-year-old son Hideyori to inherit his position. However, the five-member council that was to rule until Hideyori came of age was soon divided, and the two sides made war upon each other. In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu, a vassal of Hideyoshi, defeated his opponents at the Battle of Sekigahara (Figure 2.19), and he became shogun in 1603.

To consolidate power, Tokugawa Ieyasu rewarded loyal daimyos with gifts of land. He allocated 15 percent of Japan’s richest rice-producing land to himself and his heirs. The next-best land, about half of that available, was given to his “inside daimyos,” samurai who were related to him or who had declared their loyalty before the Battle of Sekigahara. The remaining land, less fertile or farthest away from the new capital of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), was given to the “outside daimyos,” samurai clans that had proclaimed loyalty only after his victory or that had fought against him. Ieyasu prohibited daimyos from forming alliances, including marriages, without his approval. He also required them to spend every other year in Edo, where it would be more difficult for them to formulate rebellion.

The peace and unity that Tokugawa Ieyasu’s rule brought to Japan ushered in a period of prosperity and cultural blossoming. The daimyos took control of the lands that had belonged to their samurai, and the samurai moved to the cities in which their lords’ castles were located. The daimyos established schools where the sons of their vassals studied Chinese characters, learned the Confucian classics, and were instructed in military skills. Temple schools taught the children of artisans and merchants. Tokugawa Japan boasted a high level of literacy, which supported a thriving publishing industry. In Edo alone, there were hundreds of shops in which people could buy or rent novels and other types of books. People visited restaurants and theaters in their leisure time, and those who could afford to do so traveled to Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, often at festival time.

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu also feared that Christians posed a threat to Japan, a belief Dutch and English merchants seeking trade advantages encouraged. Ieyasu was aware of hostile Portuguese and Spanish actions in India and the Philippines and did not intend to surrender control of Japan. He also feared that by adopting the foreign faith, he would give disloyal daimyos opportunities to conspire against him. He was encouraged in this belief when a Christian samurai forged a document to help another Christian samurai claim land he desired and a scandal erupted. The forger, caught, also claimed that a plan existed to kill an official of the shogun’s government.

In 1614, Ieyasu outlawed the practice of Christianity and ordered missionaries to leave the country. Japanese Christians were warned that if they did not renounce their faith, they would be killed. It was clear to Ieyasu that the best way to keep Christian influence—and other dangerous forces—out of the country was to ban the entry of foreigners and forbid Japanese to leave. Preventing Japanese from leaving the country would also keep daimyos from conspiring against him in foreign lands.

In 1624, the Spanish were banned from entering Japan. In 1639, Ieyasu prohibited the entry of the Portuguese. The Dutch, who had refrained from missionary activity, were still allowed to enter Japan to trade. However, to limit any harmful influence on their part, Dutch merchants were confined to a settlement on Dejima Island in the harbor of Nagasaki, in a walled compound they were not allowed to leave. Only licensed trade officials and translators (a position that became hereditary) could have contact with them. The English might have been extended the same rights, but finding trade with Japan not as profitable as they had hoped, they no longer sent ships. Chinese merchants were also still allowed to enter the country, but their trade was confined to Nagasaki, and they were forced to live in a special Chinese enclave. In 1635, Japanese were forbidden to leave the country except on special missions, like transacting trade with Korea, China, and Russia.

Copyright: Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). Exchange in East Asia. In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Christianity in Japan

In July 1549, Francis Xavier arrived in Japan, hoping to find success converting the Japanese to Christianity. Xavier initially struggled due to his lack of knowledge of the Japanese language and his inaccurate understanding of Japanese Buddhism. Still, he laid the foundation for a successful mission that continued to grow after he left Japan to return to India two years later. Scholars have estimated that more than 300,000 people in Japan converted to Christianity over the next fifty years. However, this brief Christian experiment ended in 1614 when the Tokugawa government outlawed the religion, beginning a period of persecution that resulted in the torture and execution of more than a thousand Japanese Christians and European missionaries. At this time, all Christian churches that had been built in Japan were destroyed, along with the works of art that had decorated them.

A sizeable portion of these Christians managed to continue to practice their faith despite the constant danger of detection by government officials. Christian works of art played an important role in helping them maintain their devotional practices, and create a sense of religious community and identity. For example, statues of the bodhisattva Kannon in a feminine form holding a child (such as the one above) appeared Buddhist on the surface, but due to similarities in iconography, could be regarded as images of the Virgin and Child by secret Christians. Devotional images with obvious Christian iconography that had no Buddhist counterpart, such as the Kobe painting of St. Francis Xavier, were more dangerous. In many cases, they had to be hidden away.

In 1920, researchers from the Kyoto Imperial University in Japan made a miraculous discovery. They found a locked chest—seemingly unopened for centuries—tied to a beam in the ceiling of an old house. When they opened it, they discovered a small collection of Christian artworks and texts. These were rare survivors from the European missions that sought to convert the Japanese people (who traditionally practiced Shinto and Buddhism) to Catholicism. This effort dramatically came to an end in 1614 when the Tokugawa government outlawed Christianity and expelled all European missionaries.

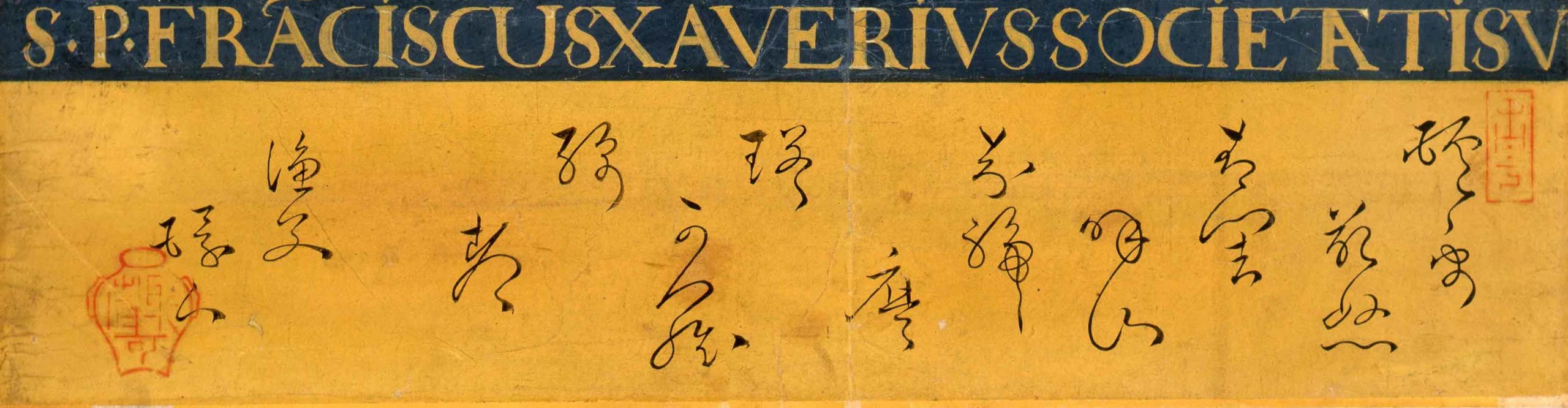

The two paintings in the chest—likely created by unknown Japanese-Christian artists—depicted the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary and St. Francis Xavier, the first Catholic missionary in Japan and a member of the Society of Jesus. Unfortunately, the box contained no documentary records that could tell us when this image of Francis Xavier was created, where or who it was made for, or how it was used. Although many of the basic facts about the painting remain the subject of debate, it is clear that the painting is an invaluable record of cultural, religious, and artistic interaction between Europe and Japan in the early modern period.

The Kobe painting of St. Francis Xavier is undeniably a product of both Japanese and European visual culture. The materials are Japanese, but the artist demonstrates some familiarity with European pictorial techniques like modeling in light and shade. The artist has also based the composition on prints of Xavier, such as those by Flemish printmakers Theodoor Galle and Hieronymus Wierix. European prints were sent to overseas missions to instruct converts in their new faith and also served as source material for non-European artists. They were a common means by which artistic knowledge circulated throughout the early modern world.

The Kobe painting of Xavier follows the basic format of the Wierix and Galle prints by depicting the saint from the waist up in a three-quarter pose. His physical appearance is consistent with textual descriptions written by those who knew him in life. These accounts stress his light complexion, beard, dark hair, and eyes always uplifted towards heaven. In his left hand, he holds a flaming heart from which a crucifix emerges. In the upper right portion of the painting, the background, a neutral dark blue field in most of the painting, transforms into dark clouds that part to reveal a golden aura that surrounds the crucifix.

Emerging from Xavier’s mouth is the Latin phrase “Satis est, Domine, satis est,” meaning “It is enough, O Lord, it is enough.” Many sources record that Xavier, when he thought no one was observing him, would open his cassock to try to cool his burning heart and would utter this phrase, marveling at the generous consolations God had sent him.

Below the image of Xavier is an inscription in Latin identifying him as a saint and a member of the Society of Jesus. His name is repeated once more, in the bottom-most portion of the painting, where Chinese characters are used to write out the words “St. Francis Xavier Sacrament” phonetically. The painting is also signed “Gyofu Kanjin,” a confusing signature that is not really a name, but instead translates to “fisherman.”

The only other clue to the artist’s identity is a red seal in the lower left portion of the painting, shaped like a pot. This is the seal of the Kanō school, a painting workshop that dominated the artistic scene of the Tokugawa period. One scholar has hypothesized that the Kobe portrait of Francis Xavier was painted by a Japanese artist who had initially trained with the Kanō, but then converted to Christianity and became a priest. This might explain the signature on the portrait, which refers to the artist as a “fisherman” perhaps meaning a “fisher of men.” [1] For the time being, however, this remains speculation.

Japanese Devotion to St. Francis Xavier

Early modern Japanese Christians were especially devoted to Xavier since he had been the first Catholic missionary to bring knowledge of the Gospel to Japan and had supposedly worked several miracles in the Japanese islands. One of the most prominent Xavierian devotees was Ōtomo Yoshishige, a sixteenth-century daimyo who, after his baptism, had taken the Christian name Francisco in honor of Xavier. In 1585, he wrote a letter to Rome asking that Xavier be canonized, so that Japanese Christians could build churches dedicated to Xavier, set up images depicting him on altars, celebrate his Mass, and pray to him for intercession. We know nothing about where the Kobe painting of Xavier was originally displayed, but if it was painted before the prohibition against Christianity, it is possible that it would have been put up in a church on an altar. One scholar has proposed that it was publicly displayed in the Jesuit church in Kyoto and later taken to Takatsuki to be concealed after Christianity was prohibited.[2] Like most things related to the Kobe St. Francis painting, this is just an educated guess.

We do have a few scattered mentions of other images of St. Francis Xavier in letters written by the Jesuit missionaries who remained in hiding in Japan after the 1614 prohibition. A 1625 letter written by a Jesuit who managed to evade the authorities mentions that he brought an image of St. Francis Xavier to a group of hidden Christians in Yamaguchi. These brief, but tantalizing, references demonstrate that although its survival was extraordinary, the painting of Francis Xavier itself was not unique. At the time it was created, it was but one example of the vibrant visual and material culture of Japanese Christianity that celebrated Francis Xavier, the “Apostle of Japan” whose mission had inaugurated the Japanese Catholic Church.

Copyright: Dr. Rachel Miller, “A portrait of St. Francis Xavier and Christianity in Japan,” in Smarthistory, June 10, 2020, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/francis-xavier-christianity-japan/.

LITERATURE

Cao Xueqin

The Story of the Stone (or The Dream of the Red Chamber) sis a novel attributed to Cao Xueqin of 18th century China. The novel shows the decline of the wealth Jia family. Cao’s own family experienced a similar decline during the Qing Dynasty. The novel portrays the experiences of closer to forty main characters and about 400 minor characters. The framework of the story tells the tale of a flower that gives life to the conscious stone in the mythic world of the past; in the main narrative, the flower and the stone are both incarnated as humans and become part of a love triangle. It also sheds light on 18th century Chinese society and probes into the ideas of truth and illusion.

Copyright: Compact Anthology of World Literature, Part Four: The 17th and 18th Centuries. University System of Georgia. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Read the entirety of The Story of the Stone through Project Gutenberg

Matsuo Basho

Haiku master, Matsuo Basho, wrote The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Basho started on his journey to the north eastern part of Japan in 1689, with his traveling compassion, Sora. Basho was hoping to get a glimpse of eternity in this dangerous and unexplored region of Japan. His travelogue is an account of various geographical and historical sites in Japan.

A haiku is a Japanese poem of three lines, with the syllable scheme of 5 syllables-7 syllables-5 syllables.

Station 1 – Prologue

Days and months are the travellers of eternity. So are the years that pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives travelling. There are a great number of the ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind- filled with a strong desire to wander.

It was only toward the end of last autumn that I returned from rambling along the coast. I barely had time to sweep the cobwebs from my broken house on the River Sumida before the New Year, but no sooner had the spring mist begun to rise over the field than I wanted to be on the road again to cross the barrier-gate of Shirakawa in due time. The gods seem to have possessed my soul and turned it inside out, and the roadside images seemed to invite me from every corner, so that it was impossible for me to stay idle at home.

Even while I was getting ready, mending my torn trousers, tying a new strap to my hat, and applying moxa to my legs to strengthen them, I was already dreaming of the full moon rising over the islands of Matsushima. Finally, I sold my house, moving to the cottage of Sampu, for a temporary stay. Upon the threshold of my old home, however, I wrote a linked verse of eight pieces and hung it on a wooden pillar.

The starting piece was:

Behind this door

Now buried in deep grass

A different generation will celebrate

The Festival of Dolls.

Station 2 – Departure

It was early on the morning of March the twenty-seventh that I took to the road. There was darkness lingering in the sky, and the moon was still visible, though gradually thinning away. The faint shadow of Mount Fuji and the cherry blossoms of Ueno and Yanaka were bidding me a last farewell. My friends had got together the night before, and they all came with me on the boat to keep me company for the first few miles. When we got off the boat at Senju, however, the thought of three thousand miles before me suddenly filled my heart, and neither the houses of the town nor the faces of my friends could be seen by my tearful eyes except as a vision.

The passing spring

Birds mourn,

Fishes weep

With tearful eyes.

With this poem to commemorate my departure, I walked forth on my journey, but lingering thoughts made my steps heavy. My friends stood in a line and waved good-bye as long as they could see my back.

Read the rest of Basho’s writings from Terebess Asia Online (TAO)

Japanese Poetry

Video URL: https://youtu.be/CJ17bWVrgho?si=63tGsE5LXVLZs_1V

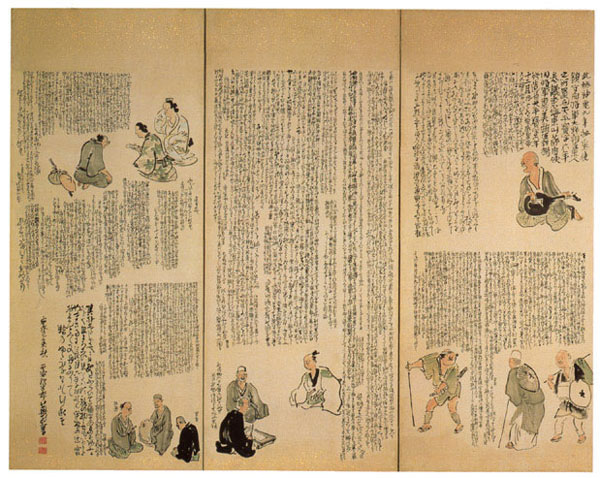

Copyright: Dr. Sonia Coman and Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “Hon’ami Kōetsu, Folding Screen mounted with poems,” in Smarthistory, November 8, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/honami-koetsu-folding-screen-with-poems/.

ARCHITECTURE

The Forbidden City

The Forbidden City is a large precinct of red walls and yellow glazed roof tiles located in the heart of China’s capital, Beijing. As its name suggests, the precinct is a micro-city in its own right. Measuring 961 meters in length and 753 meters in width, the Forbidden City is composed of more than 90 palace compounds including 98 buildings and surrounded by a moat as wide as 52 meters.

The Forbidden City was the political and ritual center of China for over 500 years. After its completion in 1420, the Forbidden City was home to 24 emperors, their families and servants during the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. The last occupant (who was also the last emperor of imperial China), Puyi (1906–67), was expelled in 1925 when the precinct was transformed into the Palace Museum. Although it is no longer an imperial precinct, it remains one of the most important cultural heritage sites and the most visited museum in the People’s Republic of China, with an average of eighty thousand visitors every day.

Construction and layout

The construction of the Forbidden City was the result of a scandalous coup d’état plotted by Zhu Di, the fourth son of the Ming dynasty’s founder Zhu Yuanzhang, that made him the Chengzu emperor (his official title) in 1402. In order to solidify his power, the Chengzu emperor moved the capital, as well as his own army, from Nanjing in southeastern China to Beijing and began building a new heart of the empire, the Forbidden City.

The establishment of the Qing dynasty in 1644 did not lessen the Forbidden City’s pivotal status, as the Manchu imperial family continued to live and rule there. While no major change has been made since its completion, the precinct has undergone various renovations and minor constructions well into the twenty-first century. Since the Forbidden City is a ceremonial, ritual and living space, the architects who designed its layout followed the ideal cosmic order in Confucian ideology that had held Chinese social structure together for centuries. This layout ensured that all activities within this micro-city were conducted in the manner appropriate to the participants’ social and familial roles. All activities, such as imperial court ceremonies or life-cycle rituals, would take place in sophisticated palaces depending on the events’ characteristics. Similarly, the court determined the occupants of the Forbidden City strictly according to their positions in the imperial family.

The architectural style also reflects a sense of hierarchy. Each structure was designed in accordance with the Treatise on Architectural Methods or State Building Standards (Yingzao fashi), an eleventh-century manual that specified particular designs for buildings of different ranks in Chinese social structure.

Public and private life

Public and domestic spheres are clearly divided in the Forbidden City. The southern half, or the outer court, contains spectacular palace compounds of supra-human scale. This outer court belonged to the realm of state affairs, and only men had access to its spaces. It included the emperor’s formal reception halls, places for religious rituals and state ceremonies, and also the Meridian Gate (Wumen) located at the south end of the central axis that served as the main entrance.

Upon passing the Meridian Gate, one immediately enters an immense courtyard paved with white marble stones in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian). Since the Ming dynasty, officials gathered in front of the Meridian Gate before 3 a.m., waiting for the emperor’s reception to start at 5 a.m.

While the outer court is reserved for men, the inner court is the domestic space, dedicated to the imperial family. The inner court includes the palaces in the northern part of the Forbidden City. Here, three of the most important palaces align with the city’s central axis: the emperor’s residence known as the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong) is located to the south while the empress’s residence, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunninggong), is to the north. The Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union (Jiaotaidian), a smaller square building for imperial weddings and familial ceremonies, is sandwiched in between. Although the Palace of Heavenly Purity was a grand palace building symbolizing the emperor’s supreme status, it was too large for conducting private activities comfortably. Therefore, after the early 18th century Qing emperor, Yongzheng, moved his residence to the smaller Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxindian) to the west of the main axis, the Palace of Heavenly Purity became a space for ceremonial use and all subsequent emperors resided in the Hall of Mental Cultivation.

The residences of the emperor’s consorts flank the three major palaces in the inner court. Each side contains six identical, walled palace compounds, forming the shape of K’un “☷,” one of the eight trigrams of ancient Chinese philosophy. It is the symbol of mother and earth, and thus is a metaphor for the proper feminine roles the occupants of these palaces should play. Such architectural and philosophical symmetry, however, fundamentally changed when the empress dowager Cixi (1835–1908) renovated the Palace of Eternal Spring (Changchungong) and the Palace of Gathered Elegance (Chuxiugong) in the west part of the inner court for her fortieth and fiftieth birthday in 1874 and 1884, respectively. The renovation transformed the original layout of six palace compounds into four, thereby breaking the shape of the symbolic trigram and implying the loosened control of Chinese patriarchal authority at the time.

The eastern and western sides of the inner court were reserved for the retired emperor and empress dowager. The emperor Qianlong (r. 1735–96) built his post-retirement palace, the Hall of Pleasant Longevity (Leshoutang), in the northeast corner of the Forbidden City. It was the last major construction in the imperial precinct. In addition to these palace compounds for the older generation, there are also structures for the imperial family’s religious activities in the east and west sides of the inner court, such as Buddhist and Daoist temples built during the Ming dynasty. The Manchus preserved most of these structures but also added spaces for their own shamanic beliefs.

Copyright: Dr. Ying-chen Peng, “The Forbidden City,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/the-forbidden-city/.

European Palaces of the Qianlong Emperor

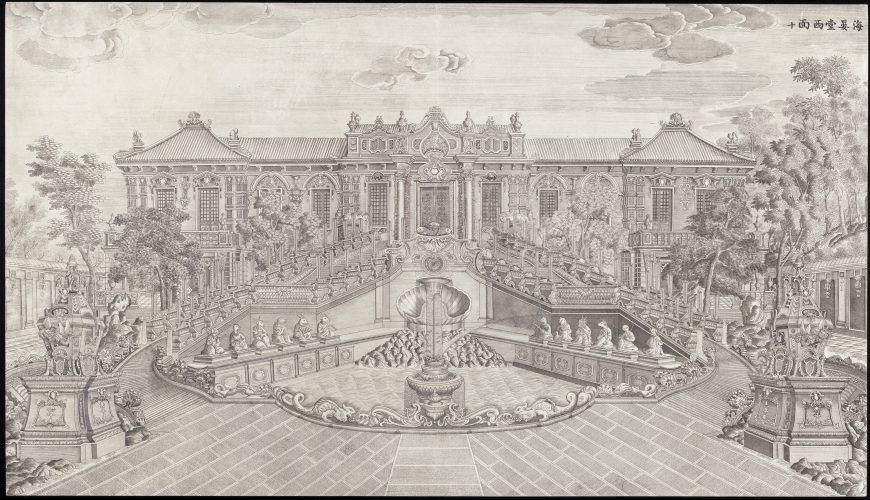

The Garden of the Eternal Spring is a larger complex made up of three large imperial gardens — The Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan), the Garden of Eternal Spring (Changchun Yuan), and the Garden of Elegant Spring (Qichun Yuan). These gardens are also sometimes called the “Old Summer Palace” in English, which inaccurately implies that this was a place of leisurely summer retreat, secondary in importance to the Forbidden City. In reality, the gardens were the primary residences of the Qing emperors for most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Garden of Eternal Spring was begun in 1749 and consisted of hundreds of acres of pavilions, palaces, landscaping, artificial hills, and water features. When one of the few privileged guests who were allowed to view the palaces arrived in the northern section of this vast complex, a surprise awaited. Here, they would suddenly encounter a sequence of stone buildings done in a hybrid Chinese-European style, known as the Xiyang Lou, or “European Palaces.”

The European Palaces were the result of a collaboration between the Qianlong emperor and a group of European Jesuit missionaries who were working at the Qing court as painters, botanists, mathematicians, and astronomers. The Jesuits are a Roman Catholic religious order founded during the 16th century who had been active as missionaries in China. Christianity had been outlawed during the reign of the Qianlong emperor’s father, however, small number of Jesuits remained in China solely as servants to the emperor and subject to his command.

In the 1740s, one of these Jesuits showed the Qianlong emperor engravings of the fountains at Versailles, the principal royal residence in eighteenth-century France. Fascinated, the Chinese emperor commissioned an Italian Jesuit painter named Giuseppe Castiglione, known as Lang Shining in China, to oversee the construction of a similar fountain. Eventually this project dramatically expanded from a single fountain to an entire complex of palaces, scenic views, and waterworks. Although the European Palaces are usually attributed to Castiglione alone, he actually collaborated on this project with the prolific Lei family of imperial Chinese architects and with other Jesuits at court, including a hydraulics expert and mathematician named Michel Benoist.

A landscape full of surprises

According to traditional Chinese garden design, a garden should include discrete scenes that are sequentially revealed to the visitor as they traverse the landscape. Each view should contain an unexpected element that would astonish the viewer in its creativity and cleverness. The European Palaces, despite their foreign appearance, are fully in line with this tradition. A wall enclosed the section of the garden where the European palaces were; only the tall roofs of the structures, covered in traditional Chinese ceramic tiles, were visible from the rest of the garden. The viewer would have no reason to suspect that the buildings were unusual until they passed through the gate and suddenly encountered this fantastical vision of Europe.

As visitors traveled through the palace complex, it continuously concealed and revealed surprises. For example, the Aviary, which held the emperor’s menagerie of peacocks and exotic birds, appeared to be entirely Chinese in design from the western façade; however, after the visitor exited the Aviary on the eastern side, they would look back over their shoulder to see a curved façade done in an exuberant European Rococo style. It would have appeared to them as if they had entered the building in China and exited in Europe.

Another visual trick was placed at the far eastern end of the European Palaces section. After descending from the Hill of Linear Perspective, the visitor would get on a boat to cross the Square Lake. On the eastern shore of the lake, Castiglione had painted twelve illusionistic scenes using European linear perspective. These paintings were meant to fool the viewer into thinking that an entire European city street had been constructed in the garden.

The Qianlong emperor never actually lived in any of the European palaces and neither did any of his consorts, as has sometimes been asserted. Instead, the function of the European palaces was to hold his enormous collections of European and European-style objects. Some of these treasures were given to the emperor as diplomatic gifts by European monarchs, while others were imported from the West or even created in China as imitations of European luxury goods.

For example, the emperor ordered the construction of a new palace, the Distant Waters Observatory, specifically to display a set of Beauvais tapestries gifted to the emperor by King Louis XV of France. Interestingly, these tapestries, designed by François Boucher, depicted imaginary scenes of China. This was a unique situation in which a European artist’s vision of Asia was hung in a fantastical European architectural setting commissioned by a Chinese emperor.

The Qianlong emperor also had a particular interest in European technology like clocks and automata. In the garden maze (in Chinese, “The Garden of Ten Thousand Flowers”), the first to be built in China, there was a marble building that housed a collection of bird automata that could sing, as well as a large music box that had been brought from Europe.

The fountains constructed throughout the garden form another collection of European-style machines and are particularly impressive from both an aesthetic and engineering point of view. The fountain in front of the Hall of Calm Seas included an ingenious water clock comprised of sculptures depicting the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac, including the rat and rabbit sculptures auctioned in 2009. Each animal was associated with a particular two-hour period of the day and water would shoot from the animal’s mouth during the appropriate time. At noon each day, water would spout from all of the animals at once. Even though these fountains were constructed using European hydraulics, their imagery was adapted to suit Chinese taste. For example, nude figures commonly decorated fountains in Europe, but were not used in the Garden of Eternal Spring. Instead, the fountains’ iconography referenced Chinese traditions, such as the animals of the zodiac, as well as other mythological stories and Daoist parables.

The European Palaces are often interpreted as expressions of the Qianlong emperor’s power. Chinese emperors throughout history have viewed themselves as having a mandate to rule everything “under Heaven” (meaning, the entire world). Several scholars have connected this idea to the European palaces, asserting that the appropriation of European architecture and technology in the Garden of Eternal Spring was meant to be seen as a visual demonstration of Qing superiority over Europe and Qianlong’s dominion over the known world. However, a recent alternative interpretation proposes that the Qianlong emperor was not interested in literally colonizing Europe. Instead, we should view his European Palaces as a means of “collecting” Europe. The emperor and his rare guests were always aware that the built structures in the garden were a fantasy of Europe conjured up at the emperor’s command, demonstrating his mastery over reality itself.

Copyright: Dr. Rachel Miller, “The European Palaces of the Qianlong Emperor, Beijing,” in Smarthistory, July 31, 2019, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/yuanming-yuan/.

Angkor War

Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, Cambodia is the largest religious monument in the world. Angkor Wat, translated from Khmer (the official language of Cambodia), literally means “City Temple.” As far as names go this is as generic as it gets. Angkor Wat was not the original name given to the temple when it was built in the 12th century. We have little knowledge of how this temple was referred to during the time of its use, as there are no extant texts or inscriptions that mention the temple by name—this is quite incredible if we consider the fact that Angkor Wat is the greatest religious construction project in Southeast Asia.

A possible reason why the temple’s original name may have never been documented is that it was such an important and famous monument that there was no need to refer to it by its name. We have several references to the king who built the temple, King Suryavarman II, and events that took place at the temple, but no mention of its name.

Historical context

Angkor Wat is dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu who is one of the three principal gods in the Hindu pantheon (Shiva and Brahma are the others). Among them he is known as the “Protector.” The major patron of Angkor Wat was King Suryavarman II, whose name translates as the “protector of the sun.” Many scholars believe that Angkor Wat was not only a temple dedicated to Vishnu but that it was also intended to serve as the king’s mausoleum in death.

The construction of Angkor Wat likely began in the year 1116 C.E.—three years after King Suryavarman II came to the throne—with construction ending in 1150, shortly after the king’s death. Evidence for these dates comes in part from inscriptions, which are vague, but also from the architectural design and artistic style of the temple and its associated sculptures.

The building of temples by Khmer kings was a means of legitimizing their claim to political office and also to lay claim to the protection and powers of the gods. Hindu temples are not a place for religious congregation; instead, they are homes of the god. In order for a king to lay claim to his political office he had to prove that the gods did not support his predecessors or his enemies. To this end, the king had to build the grandest temple/palace for the gods, one that proved to be more lavish than any previous temples. In doing so, the king could make visible his ability to harness the energy and resources to construct the temple and assert that his temple was the only place that a god would consider residing in on earth.

The building of Angkor Wat is likely to have necessitated some 300,000 workers, which included architects, construction workers, masons, sculptors, and the servants to feed these workers. Construction of the site took over 30 years and was never completely finished. The site is built entirely out of stone, which is incredible as close examination of the temple demonstrates that almost every surface is treated and carved with narrative or decorative details.

Carved bas reliefs of Hindu narratives

There are 1,200 square meters of carved bas reliefs at Angkor Wat, representing eight different Hindu stories. Perhaps the most important narrative represented at Angkor Wat is the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, which depicts a story about the beginning of time and the creation of the universe. It is also a story about the victory of good over evil. In the story, devas (gods) are fighting the asuras (demons) in order reclaim order and power for the gods who have lost it. In order to reclaim peace and order, the elixir of life (amrita) needs to be released from the earth; however, the only way for the elixir to be released is for the gods and demons to first work together. To this end, both sides are aware that once the amrita is released there will be a battle to attain it.

The relief depicts the moment when the two sides are churning the ocean of milk. In the detail above you can see that the gods and demons are playing a sort of tug-of-war with the Naga or serpent king as their divine rope. The Naga is being spun on Mt. Mandara represented by Vishnu (in the center). Several things happen while the churning of milk takes place. One event is that the foam from the churning produces apsarasor celestial maidens who are carved in relief throughout Angkor Wat (we see them here on either side of Vishnu, above the gods and demons). Once the elixir is released, Indra is seen descending from heaven to catch it and save the world from the destruction of the demons.

Angkor Wat as temple mountain

An aerial view of Angkor Wat demonstrates that the temple is made up of an expansive enclosure wall, which separates the sacred temple grounds from the protective moat that surrounds the entire complex (the moat is visible in the photograph at the top of the page). The temple proper is comprised of three galleries (a passageway running along the length of the temple) with a central sanctuary, marked by five stone towers.

The five stone towers are intended to mimic the five mountain ranges of Mt. Meru—the mythical home of the gods, for both Hindus and Buddhists. The temple mountain as an architectural design was invented in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian architects quite literally envisioned temples dedicated to Hindu gods on earth as a representation of Mt. Meru. The galleries and the empty spaces that they created between one another and the moat are envisioned as the mountain ranges and oceans that surround Mt. Meru. Mt. Meru is not only home to the gods, it is also considered an axis mundi. In designing Angkor Wat in this way, King Suryavarman II and his architects intended for the temple to serve as the supreme abode for Vishnu. Similarly, the symbolism of Angkor Wat serving as an axis mundi was intended to demonstrate the Angkor Kingdom’s and the king’s central place in the universe. In addition to envisioning Angkor Wat as Mt. Meru on earth, the temple’s architects, of whom we know nothing, also ingeniously designed the temple so that embedded in the temple’s construction is a map of the cosmos (mandala) as well as a historical record of the temple’s patron.

Angkor Wat as a mandala

According to ancient Sanskrit and Khmer texts, religious monuments and specifically temples must be organized in such a way that they are in harmony with the universe, meaning that the temple should be planned according to the rising sun and moon, in addition to symbolizing the recurrent time sequences of the days, months, and years. The central axis of these temples should also be aligned with the planets, thus connecting the structure to the cosmos so that temples become spiritual, political, cosmological, astronomical, and geo-physical centers. They are, in other words, intended to represent microcosms of the universe and are organized as mandalas—diagrams of the universe.

Video URL: https://youtu.be/fPc20_vtlaM?si=dD4FGahLFwleEbEN

Copyright: Dr. Melody Rod-ari, “Angkor Wat,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/angkor-wat/.

PERFORMING ARTS

Kabuki and Bunraku

Video URL: https://youtu.be/oc3dWwbctw4?si=1TdkUSdw3WRZTG_r

Copyright: Crash Course 2024

Kabuki Prints

Kabuki theatre developed from a popular entertainment performed by female dancers in Kyoto. This was banned in 1629 as detrimental to public morals, and replaced by young men’s Kabuki. From 1652 this was replaced by Kabuki performed by adult males. Although the government attempted to regulate Kabuki, the theatres, and their neighboring teahouses and houses of often homosexual assignation became thriving centers of urban culture, part of the ‘floating world’. The leading actors, including the onnagata, male performers of female roles, influenced fashion and taste and quickly became the subject of popular woodblock prints. It is likely that between one third and a half of prints published in the Edo period depicted Kabuki actors.

Three schools of artists specialized in designing actor prints. In the first half of the eighteenth century the Torii school was prominent. They started out using an exaggerated, muscular drawing style which captured the action of the animated aragoto (‘rough stuff’) style of the Kabuki. Later the Torii were eclipsed by the Katsukawa school. The founder, Shunshō and his contemporary Bunchō, were more restrained, and concentrated on capturing the likenesses of the actors (nigao-e). The Katsukawa school gave way to the Utagawa school (Toyokuni and Kunisada) from the 1790s onwards, and a return to a more florid schematic style. In addition, the enigmatic Tōshūsai Sharaku appeared briefly like a passing comet in 1794–95. In 1794 he produced a unique group of almost thirty highly individualized portraits in the ōkubi-e (‘big head’) format. These exaggerate the expressive quirks and gestures of the leading actors of his day.

It is often possible to date actor prints by referring to surviving printed banzuke (playbills) and yakusha hyōbanki (actor critiques). This is useful when studying the chronological development of an Ukiyo-e artist’s style.

‘Gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’

The Kabuki ‘armor-tugging’ scene originated in the play about the revenge of the Soga brothers. It involved a struggle between the characters Soga no Gorō (right) and Kobayashi Asahina (left). However, it came to be inserted into other unrelated plays and in the summer of 1717 it was due to be performed ‘underwater’ in the play ‘The Battle of Coxinga’ (Kokusenya gassen), at the Ichimura Theatre. A large signboard was painted to hang outside the theatre, showing Hiroji bursting out through the side of the boat to grasp Danzō’s armor. In the event, the scene was cancelled, but the signboard painting, now lost, may well have been the inspiration for this print, since the Torii artists were responsible for producing all of the signboards, prints and illustrated programmes for the Kabuki theatres in Edo.

The characteristic acting style of Edo was known as aragoto (‘rough stuff’). The lively drawing style of the early Torii artists admirably catches the boisterous energy of the action. A later Japanese critic describes their figures as typically having ‘gourd-shaped legs and wriggling worm lines’. The impact of this print is increased by the application by hand of orange lead pigment (tan).

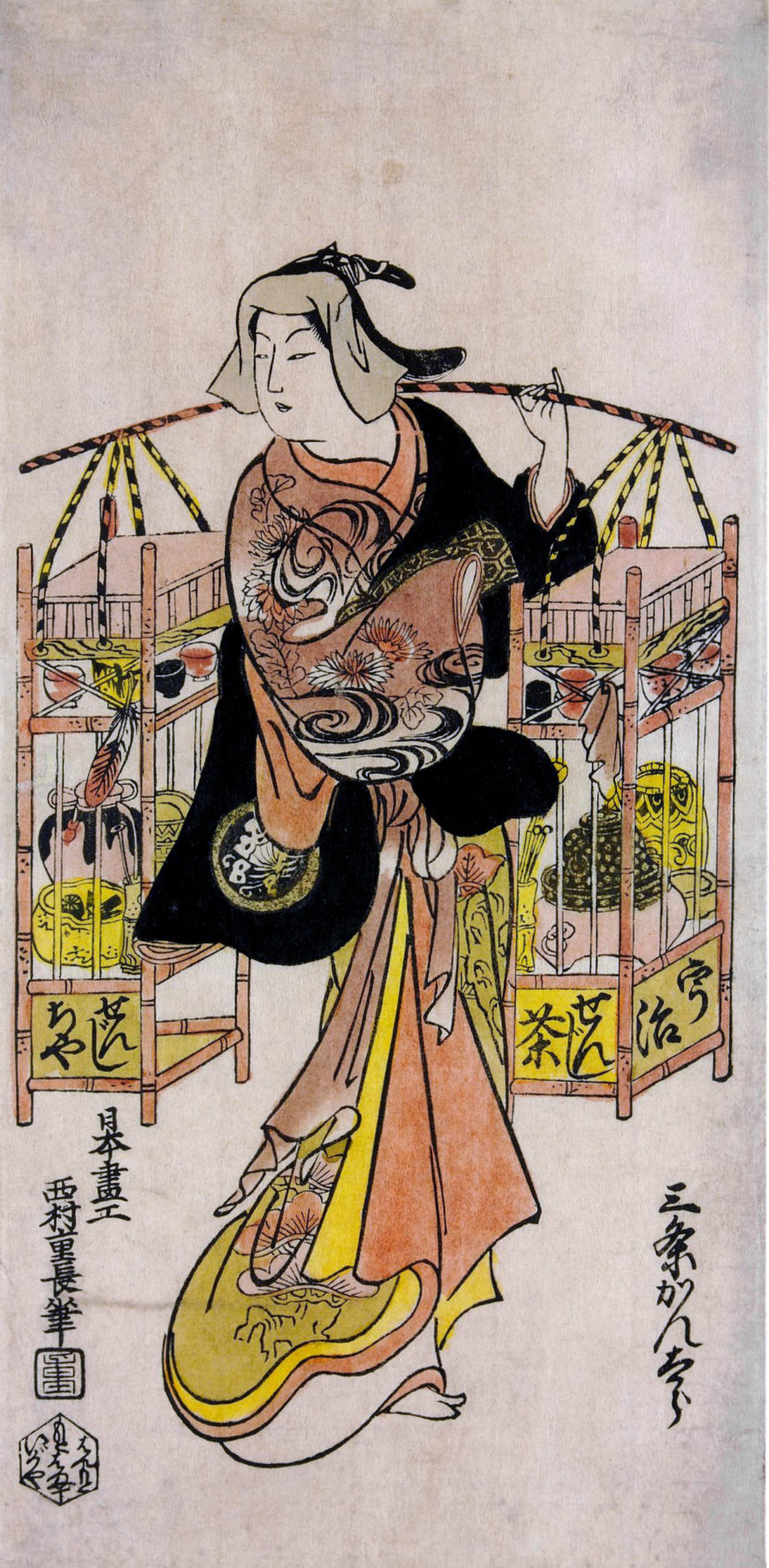

Female impersonators

The onnagata (female impersonator) Sanjō Kantarō plays the Kabuki role of a seller of Uji tea carrying her portable stall. The print is hand-colored in shades of red, pink and purple, all now somewhat faded. Glossy glue has been applied to the black over-kimono to give the effect of lacquer and there are sprinklings of brass dust on the obi sash, the butterfly crest on the sleeve and the lid of the kettle.

Kantarō has slipped off the right sleeve of the over-kimono to show off the elaborate under-kimono patterned with designs of waves and chrysanthemums. The overall elegance of the figure, especially the cocked little finger, suggests the he may be playing the role of some famous beauty in humble disguise. The tea implements are also drawn with great care, and we can see clearly all the details of the brazier and kettle with bamboo tea-scoop, tea jar, water pot and small cups.

Large head portraits

The artist Tōshūsai Sharaku worked for a only a brief period, for ten months between 1794 and 1795. Very little is known of him before or after this period and his identity is the object of much conjecture among historians of Japanese art. The most likely theory is that he was one Saitō Jūrobei originally a nō actor in the service of the Lord of Awa.

Sharaku had a special talent for characterizing his subjects by differentiating their facial features. Furthermore, the development of the okubi-e (‘large head’ portraits) in the mid-1790s encouraged a more penetrating analysis of character. This print shows a scene from the play ‘A Medley of Tales of Revenge’ (Katakiuchi noriai-banashi) performed at the Kiri Theatre in the fifth month of 1794. The two subjects are strongly contrasted. On the right, Wadaemon in the role of Bodara no Chōzaemon, a customer visiting a house of pleasure, with his sharp, angular features, pleads with Kanagawaya Gon, the chubby boatman, played by Konozō. The boatman’s narrowed eyes and snub nose suggest that he is bent on striking a hard bargain.

‘Wait a moment!’

Kunimasa (1773–1810) designed this print as a tribute to the great Ebizō (formerly Ichikawa Danjūrō V) on the occasion of his retirement from the Kabuki stage in 1796. He chose to depict him in the shibaraku scene, one of the most famous in all Kabuki drama. With a thundering cry of ‘shibaraku!‘ (‘wait a moment!’), the hero bursts on to the hanamichi walkway from the back of the theatre just in time to save the characters on stage from certain death. Perhaps, in this print, Ebizō is depicted on the very brink of calling out.

In this okubi-e (‘large-head portrait’), Kunimasa gives us an unusual profile view of Ebizō. The main elements of the striking costume and make-up are clearly visible: the ‘five-spoke wheel’ wig with, top right, the paper ‘strength’ decorations under the black lacquer court hat; the fierce red make-up; the green jacket with design of stylized cranes; and most significant of all, the familiar persimmon-colored costume with the three white interlocking squares (mimasu), which are the Ichikawa family emblem.

Tribute to a Kabuki actor

This print marks the occasion of the actor Danjūrō VIII’s temporary departure from the Edo stage in 1849 when he travelled to Osaka to visit his father, Danjūrō VII, who had been sent into exile there some seven years earlier under the severe Tempō Reforms.

To honor their idol, Danjūrō VIII, members of two haiku poetry clubs—the Shimba and the Uogashi clubs located in the fish market districts of Edo—banded together and commissioned the large de-luxe-edition print from Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). He chose as his subject a monster carp kite, appropriate to his sponsors and also to the time of year: Boys’ Day Festival is celebrated on the 5th day of the 5th month, when giant carp streamers are flown from poles. A carp ascending a waterfall was also one crest used by the Danjūrō lineage of actors. The design includes a cloth banner painted with a portrait of Shōki, ancient Chinese queller of demons. As a further tribute to the Danjūrō line, Shōki is given the features of the father, while the leaping carp, representing perseverance, may symbolize the son.

Copyright: The British Museum, “Kabuki actor prints,” in Smarthistory, March 4, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/kabuki-actor-prints/.

VISUAL ARTS

Chinese Nature Imagery

Shen Zhou, A Spring Gathering

As we open the painting from the right, a gentleman sits in the doorway of a modest studio or residence located among rolling hills. A serving boy stands beside him holding a scroll. They are waiting for the arrival of the gentleman’s friends. One friend with a walking stick is crossing the small bridge. His boat is moored nearby. Further left, another scholar approaches by boat, bringing a box of food and a jar of wine. His serving boy is rowing the boat.

The scene is set in a beautiful mountain river landscape. Sprouting willows and blossoming peach trees suggest it is springtime. The artist is Shen Zhou (1427–1509), an elite painter considered one of the Four Masters of Ming.

In his remarks at the far left, Shen Zhou dedicated the painting to Hua Fang (1407–1487). Hua was from a prominent wealthy family and was known for his charitable acts. He is probably the figure seated inside the pavilion. Gardens and estates were considered symbols of wealth, cultivation, and social status. Artists during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) often honored their patrons by portraying them in a garden studio, thus commenting on the owner’s character and aesthetic taste. The painting here should not be taken as a realistic depiction of either Hua or his property. Rather, Shen was suggesting Hua as a cultivated host in a well-designed, natural-looking garden.

The scroll has quite a few collector seals of the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1735–96). He also added three poetic inscriptions in 1765, 1782, and 1791 across the top of the painting, and a fourth one in 1793 before the beginning of the painting. Such continuous attention clearly indicates the emperor’s admiration for this work. Wen Zhengming (1470–1559), the star pupil of Shen Zhou, wrote a long inscription in 1545 in an attachment to the painting, commemorating his teacher. These seals and comments compose a vivid history of the painting’s circulation.

Copyright: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, “Shen Zhou, A Spring Gathering,” in Smarthistory, July 16, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/shen-zhou-spring-gathering/.

One Hundred Birds hanging scroll

This embroidered hanging scroll, depicting a scene known as “One Hundred Birds” (Bainiao tu 百鸟图), is a stunning example of Guangdong embroidery (also known as Yue embroidery Yuexiu 粤绣): filled with naturalistically depicted birds, animals, and plants, and worked in a rich range of stitches. It displays some of the most characteristic features of this handicraft tradition: densely filled designs; surface complexity created through varied stitches (like long and short alternating stitches, knot stitch, and stitches simulating fur and feathers). The palette is also characteristic with its use of warm and mellow golden browns, beiges, and creams to render the tree and birds, contrasted with blue shades which highlight and bring depth to the forms. Dimensionality was also achieved in Guangdong embroidery through the application of couched metallic thread (Dingjin xiu 钉金绣), sometimes with raised relief effects, or the addition of unusual materials like pearls or peacock feathers.

“One Hundred Birds” was a common subject matter in art from the Guangzhou region, popular for its celebration of nature and its auspicious meaning. Sometimes known as the “Hundred Birds paying court to the Phoenix” (Bainiao chao feng 百鸟朝凤), the phrase carries the meaning of “Peace under a wise ruler,” since the central phoenix is considered the king of the birds and hence a symbol of the emperor.

Despite the title, fewer than 100 birds are represented (the title functions figuratively to convey the idea of a large number). The birds depicted include the crane, a symbol of longevity; the pheasant, a symbol of wealth and good wishes; and mandarin ducks, a symbol of marital happiness. Most are paired, a common feature of Chinese visual depictions of birds and animals, and a nod to the importance of balancing male and female to create harmony and unity. There are also many different flowers, including the peony, a symbol of summer and wealth, as well as irises, wisteria, and lots of butterflies. In sum, the scene conveys ideas of seasonal harmony and good fortune, and it demonstrates the complex arrangements of auspicious motifs that developed during the Ming and Qingdynasties. But this hanging also has much to tell us about the development of both artistic and commercial embroidery through the late imperial period.

Copyright: Dr. Rachel Silberstein, ““One Hundred Birds” hanging scroll,” in Smarthistory, August 4, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/one-hundred-birds-hanging-scroll/.

Landscape: tea sipping under willows

It is a hot summer day. Willow trees stand lushly along the river bank. Under the shade, three robed gentlemen sit on the ground enjoying some tea. The scholar on the left, bareheaded, is pouring tea from a teapot for himself after having served his friends. The other two have on a fisherman’s hat and an official’s cap. The three figures are likely recluse scholar-officials. With tea in hands, they are about to start a lively conversation. Beside them, a servant is fanning a portable stove to boil some more tea. Surrounding the scholars are portable shelves filled with teaware. They are of various colors, sizes, and shapes. Small in size, this album leaf is finely painted with exquisite details.

Tea was first used in China in ancient times as a medicine. It became a popular beverage during the Tang dynasty (618–907) when the first book on tea was written. Tea was compressed into dried tea cakes, then ground and brewed in water. During the Song dynasty (960–1279), tea was made from finely ground tea powder. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Chinese people began to drink tea by soaking dried tea leaves in boiling water inside a teapot. Chinese people continue to drink tea this way today.

Tea drinking has been an essential part of Chinese culture for centuries. Through the practice of generations of elites and Buddhist monks, tea tasting evolved into a fine art. Elites and monks were so fond of tea that they developed rituals around it and required certain ways to cultivate and prepare the tea. They also designed special teaware for its making and drinking. Tea culture remains an important part of life in present-day China. Tea is served at holiday parties, social gatherings, or when guests come to visit.

Copyright: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, “Landscape: tea sipping under willows,” in Smarthistory, July 6, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/landscape-tea-sipping-under-willows/.

Hua Yan, Pheasant, Bamboo, and Chrysanthemum

Video URL: https://youtu.be/Sfz1iSj915s?si=3I42ZWBgve3ie2AM

Copyright: Dr. Kristen Loring Brennan and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Hua Yan, Pheasant, Bamboo and Chrysanthemum,” in Smarthistory, June 1, 2022, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hua-yan-pheasant/.

Conyi, Cloudy Mountains

Video URL: https://youtu.be/F9SMvVtKxXM?si=FEieS5-PmkddiJuq

Copyright: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Congyi, Cloudy Mountains,” in Smarthistory, March 8, 2021, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/congyi-cloudy-mountains/.

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (The Great Wave)

Katsushika Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, also called The Great Wave, has become one of the most famous works of art in the world—and debatably the most iconic work of Japanese art. Initially, thousands of copies of this print were quickly produced and sold cheaply. Despite the fact that it was created at a time when Japanese trade was heavily restricted, Hokusai’s print displays the influence of Dutch art and proved to be inspirational for many artists working in Europe later in the 19th century.

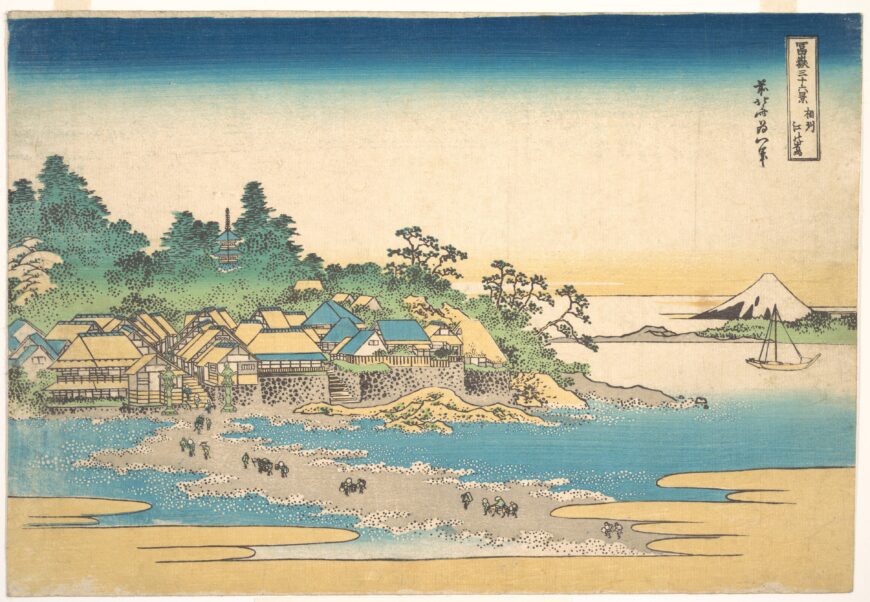

Under the Wave off Kanagawa is part of a series of prints titled Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, which Hokusai made between 1830 and 1833. It is a polychrome (multi-colored) woodblock print, made of ink and color on paper that is approximately 10 x 14 inches. All of the images in the series feature a glimpse of the mountain, but as you can see from this example, Mount Fuji does not always dominate the frame. Instead, here, the foreground is filled with a massive cresting wave. The threatening wave is pictured just moments before crashing down on to three fishing boats below. Under the Wave off Kanagawa is full of visual play. The mountain, made tiny by the use of perspective, appears as if it too will be swallowed up by the wave. Hokusai’s optical play can also be lighthearted, and the spray from top of the crashing wave looks like snow falling on the mountain.

Hokusai has arranged the composition to frame Mount Fuji. The curves of the wave and hull of one boat dip down just low enough to allow the base of Mount Fuji to be visible, and the white top of the great wave creates a diagonal line that leads the viewers eye directly to the peak of the mountain top.

Across the thirty-six prints that constitute this series, Hokusai varies his representation of the mountain. In other prints the mountain fills the composition, or is reduced to a small detail in the background of bustling city life.

Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo (now Tokyo), Japan. During the artist’s lifetime he went by many different names; he began calling himself Hokusai in 1797. Hokusai discovered Western prints that came to Japan by way of Dutch trade. From the Dutch artwork Hokusai became interested in linear perspective. Subsequently, Hokusai created a Japanese variant of linear perspective. The influence of Dutch art can also be seen in the use of a low horizon line and the distinctive European color, Prussian blue.

Hokusai was interested in oblique angles, contrasts of near and far, and contrasts of manmade and the natural. These can be seen in Under the Wave off Kanagawa through the juxtaposition of the large wave in the foreground which dwarfs the small mountain in the distance, as well as the inclusion of the men and boats amidst the powerful waves.

Mount Fuji is the highest mountain in Japan and has long been considered sacred. Hokusai is often described as having a personal fascination with the mountain, which sparked his interest in making this series. However, he was also responding to a boom in domestic travel and the corresponding market for images of Mount Fuji. Japanese woodblock prints were often purchased as souvenirs. The original audience for Hokusai’s prints was ordinary townspeople who were followers of the “Fuji cult” and made pilgrimages to climb the mountain, or tourists visiting the new capital city. Although the skyscrapers in Tokyo obscure the view of Mount Fuji today, for Hokusai’s audience the peak of the mountain would have been visible across the city.

Copyright: Leila Anne Harris, “Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (The Great Wave),” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 16, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hokusai-under-the-wave-off-kanagawa-the-great-wave/.

Korean Ceremonial Robes

A “gujangbok” is a ceremonial robe worn by the Joseon king, adorned with nine symbols, either painted or embroidered, representing the consummate authority and virtue of the king. The gujangbok was a key component of “myeonbok,” the official ceremonial attire worn by the emperor, king, crown prince, and crown grandson from the Goryeo period (918–1392) through the Joseon period (1392–1897) and Korean Empire (1897–1910).

The myeonbok consisted of eleven different pieces of apparel:

- gyu (圭, tablet),

- myeon (冕, imperial crown),

- ui (衣, outer jacket, such as the gujangbok),

- sang (裳, skirt),

- daedae (大帶, belt),

- jungdan (中單, inner robe),

- pae (佩, accessories),

- pyeseul (蔽膝, decorative panel),

- su (綬, ornament),

- mal (襪, socks), and

- seok (舃, shoes).

Two gujangboks from the National Museum of Korea have been designated as Important Folklore Cultural Heritage 66.

In addition to festive ceremonies and auspicious occasions (such as royal weddings), myeonbok was also worn for ancestral rites, agricultural rites, and for funerary rituals after a death in the royal family. Derived from the official ceremonial attire of China, myeonbok featured a number of details that reflected the rank of the person wearing it, such as the number of beaded lines on the imperial crown and the number of emblems on the jacket and skirt. For example, the myeonbok of an emperor had twelve beaded lines and twelve emblems, while that of a king had nine beaded lines and nine emblems, and that of a crown prince had eight beaded lines and seven emblems. Following this protocol, the gujangbok of the Joseon king had nine emblems, while that of the crown prince had seven emblems.

Embodying the majesty of a king

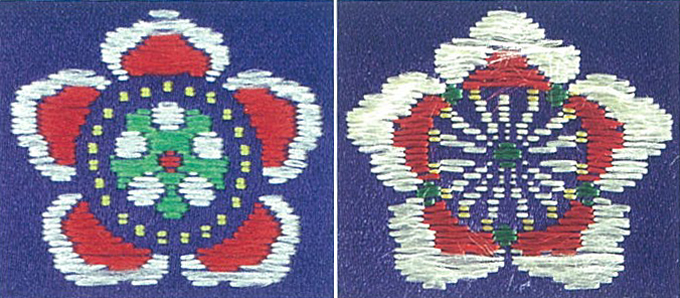

Notably, both of the gujangboks from the National Museum of Korea consist of two actual garments: a hyeonui (black outer jacket) and a jungdan (inner robe). One of the gujangboks is made from eunjosa (plain silk gauze), a thin silk fabric formed by weaving a twist of two warp threads with the weft thread, while the other is made from gapsa (fine silk gauze), a silk fabric wherein the weaves form an even pattern of small rhombuses.

In both cases, the hyeonui and jungdan consist of a single layer of cloth, with double layers forming the hems of the sleeves and skirt, as well as the collar, which takes the form of a lowercase “y.” There are four buttons on the interior of the jacket: three along the line where the sleeve meets the chest and one in the center of the collar. These buttons were likely used to respectively attach the belt and a separate round collar worn around the neck. Extra padding is sewn inside the shoulders and armpits, and both the inner and outer coat strings are made from double layers of fabric.

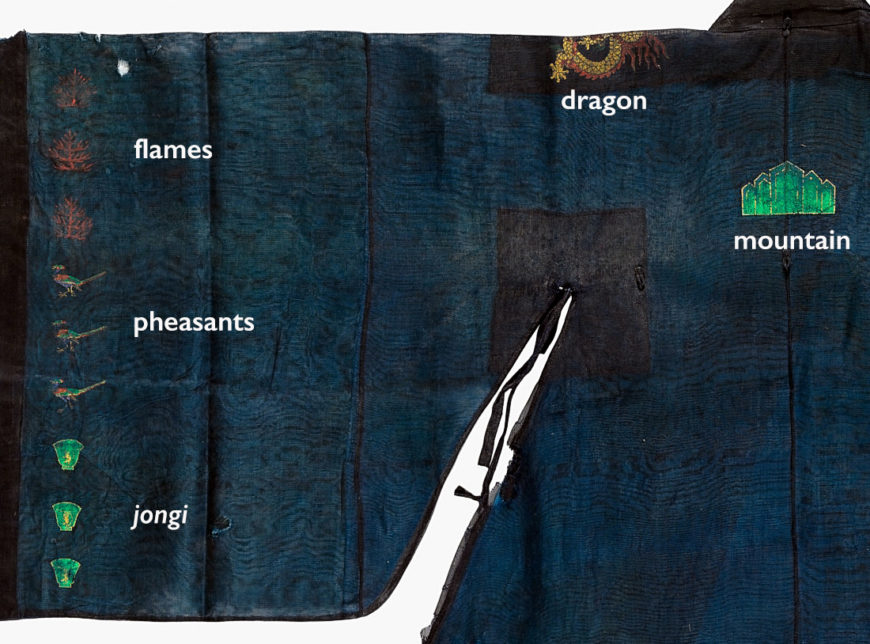

Each gujangbok is adorned with nine emblems symbolizing the virtues required for a king to rule a country: five emblems representing yang on the hyeonui and four emblems representing yin on the sang (裳, skirt) and pyeseul (蔽膝, decorative panel). The five emblems painted on the hyeonui are a dragon, mountain, fire, pheasant, and jongi (a pair of ritual vessels with a tiger and monkey design). Symbolizing mystical transformation, a dragon is painted on each shoulder, facing one another.

On the back of the robe is a mountain, representing the world as the king’s dominion. On the back of each sleeve (running parallel to the hem) is a vertical line of nine small emblems: three flames (representing splendor), three pheasants (symbolizing the beauty of writing), and three jongi (symbolizing filial piety). The jongi vessels on the right sleeve have a tiger design (symbolizing courage), while those on the left sleeve have a monkey design (symbolizing wisdom).

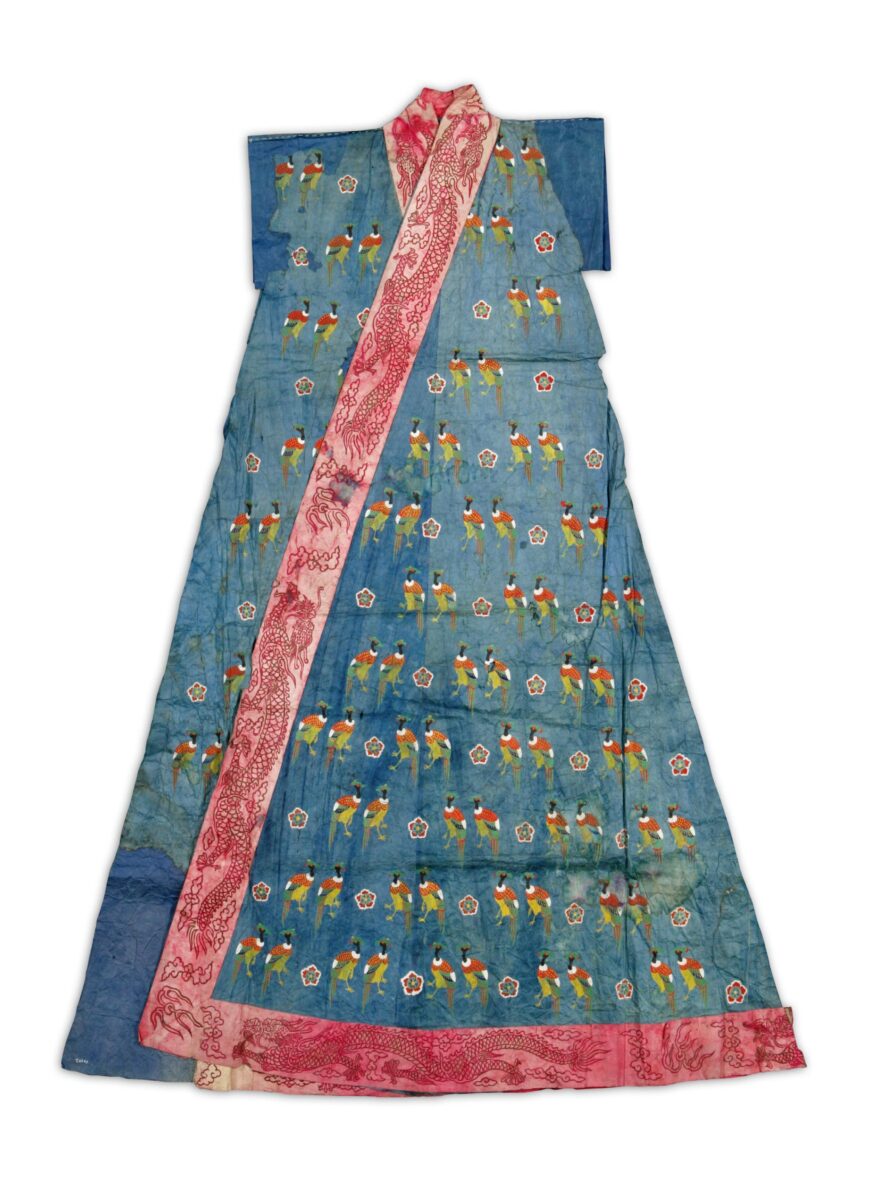

A jeogui (翟衣) is an elegant ceremonial robe with a pheasant pattern, which was worn by Joseon queens on the most formal occasions. In addition to a jeogui, the queen’s formal attire also included an array of extravagant ornaments and accessories, including a jeokgwan (queen’s crown), hapi (decorative sashes), and pyeseul (an apron-like sash). In Korea, the tradition of the jeogui dates back to 1370 (nineteenth year of Goryeo’s King Gongmin), when the Goryeo Dynasty adopted the official ceremonial attire of China’s Ming Dynasty (明, 1368–1644). The jeogui legacy can be roughly divided into three phases: the early period, from the introduction of the jeogui through the fall of the Ming (1644); the middle period, when the Joseon Dynasty officially established and practiced its own jeogui system; and the late period, when the jeogui system was revised in conjunction with the founding of the Korean Empire (1897–1910). Dating from the late period, the jeogui that is housed at the National Museum of Korea is actually a paper replica that was used as a model for producing a silk jeogui. Consisting solely of the torso, without sleeves, the jeogui is painted with a pattern symbolizing the empress of the imperial court, containing twelve rows of five-colored pheasants and numerous ihwa motifs (a type of white plum blossom).

In 1403, the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty sent Joseon an entire set of official robes for both the king and queen. After that, the Ming sent Joseon a set of official robes for the queen on fifteen separate occasions from 1405 to 1625. According to the international hierarchy of the time, Joseon was considered to be two ranks lower than the Ming. Thus, the jeogui sets that were sent by the Ming did not correspond to those of the Ming empress, but rather to those of Ming women whose husbands held the highest government posts. Those sets included crowns that were decorated with beads and seven jade-colored pheasants, red ceremonial robes with wide sleeves, vests adorned with embroidered pheasants, and decorative sashes to be worn over the robe. In 1750, after the fall of the Ming, Joseon finally established its own jeogui system. As documented in Illustrated Royal Weddings (國婚定例) and Illustrated Supplement to the Five Rites of State: Follow-up and Auxiliary Edition (國朝續五禮儀補序例), the Joseon kings wore a gujangbok robe with nine symbols, while the queens wore a jeogui with nine rows of pheasants. This standard was maintained until the end of the Joseon Dynasty.