6 CENTRAL ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

Brief History of South Asia

Understanding geography is particularly important for the study of art of South Asia, not only because the topography of the region is so diverse, but also because, for many who live on the subcontinent, the landscape itself is considered to be sacred and often appears as a main subject in works of art. Today, the region of South Asia can include the nation-states of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Scholars also use the term “Indian subcontinent” to refer to the broader region of mainland South Asia and the countries that comprise the geographic formation that dominates this southern part of Asia. Historically, the term “India” (or Hindustan) was used by people living outside this region to refer to the land beyond the Indus River.

Studying the geography of South Asia can also be a way to better understand the people who created or commissioned works of art. In addition, maps and depictions of landscapes can provide insight into transitions of political power, the territorial desires of rulers, as well as the places where artists lived and worked. Contemporary maps of the Indian subcontinent often utilize satellite images and focus on geo-political boundaries. But these contemporary maps are only one perspective of the geography of South Asia.

Indo-Gangetic Plain

One of the most famous rivers in South Asia is the Ganges River, which runs along the northern and eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent just below the Himalayan mountain range. The fertile land on either side of the Ganges River is known as the Gangetic Plain. This large region has long been home to important cities, artistic sites, and cultural activity. The Gangetic Plain encompasses present-day Bangladesh, parts of Nepal and Bhutan, as well as areas within the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal in India.

Another important river in South Asia, the Indus River, has also been a center for cultural activity for millennia. The Indus begins in the high mountains of western Tibet then flows down through Kashmir as well as through the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Punjab, and Sindh provinces in Pakistan, ultimately emptying into the Arabian Sea, just south of the city of Karachi.

These two rivers—the Indus and the Ganges—and their surrounding landscape form an area known as the Indo-Gangetic Plain, which crosses the northern part of the Indian subcontinent and includes both its northeastern and northwestern regions.

The Deccan + the South

The Deccan Plateau is a large triangular plateau of basalt and granite that rises between the coastal mountain ranges of the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, just below the Vindhya mountains. The Deccan Plateau crosses the border of several states in India including Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana. Historically, this region was home to important kingdoms whose rulers were great patrons of art and architecture. The Deccan is also a significant area for agriculture and responsible for producing a variety of goods including grains and cotton. Today, some of the largest cities in India are in the Deccan, including Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Pune. The Deccan Plateau, along with its coastal boundaries (the Coromandel Coast on the east and the Malabar Coast on the west), encompass the entire southern region of the Indian subcontinent.

The North + West

Between the Gangetic Plain (to the north and east), the Vindhya mountains (to the south), and the Indus River valley (to the west) is a small, but important region that includes the states of Chattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttarakhand in India. This northern and western region of the subcontinent has long been home to important artistic and cultural centers, including those of the great Rajput chiefs who were major patrons of art and architecture.

Understanding the geography of South Asia has never been a straight-forward task. Geo-political borders can be sources of tension, even violence, in South Asia today and often obscure shared artistic practices that cross or disrupt boundaries of contemporary nation-states. As historians and students of South Asian art it is helpful to remember that many borders are new, and that people of the past had very different conceptions of their home and their place within the world. Furthermore, while understanding geography is important for the study of South Asia, it provides only one perspective from which to explore the diverse visual and material culture from this region.

Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi, “Geographic regions of South Asia,” in Smarthistory, August 30, 2021, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/geographic-regions-south-asia/.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Hinduism

Hinduism developed over many centuries from a variety of sources: cultural practices, sacred texts, and philosophical movements, as well as local popular beliefs. The combination of these factors is what accounts for the varied and diverse nature of Hindu practices and beliefs. Hinduism developed from several sources.

Prehistoric and Neolithic culture, which left material evidence including abundant rock and cave paintings of bulls and cows, indicating an early interest in the sacred nature of these animals. (3)

The Hindu Theology of Samsara

Common to virtually all Hindus are certain beliefs, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Belief in many gods, which are seen as manifestations of a single unity. These deities are linked to universal and natural processes.

- Preference for one deity while not excluding or disbelieving others.

- Belief in the universal law of cause and effect (karma) and reincarnation.

- Belief in the possibility of liberation and release (moksha) by which the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara) can be resolved. (3)

The concept of Samsara is reincarnation, the idea that after we die our soul will be reborn again in another body — perhaps in an animal, perhaps as a human, perhaps as a god, but always in a regular cycle of deaths and resurrections.

Another concept is Karma , which literally means “action,” the idea that all actions have consequences, good or bad. Karma determines the conditions of the next life, just like our life is conditioned by our previous karma. There is no judgement or forgiveness, simply an impersonal, natural and eternal law operating in the universe. Those who do good will be reborn in better conditions while those who are evil will be reborn in worse conditions.

Dharma means “right behavior” or “duty,” the idea that we all have a social obligation. Each member of a specific caste has a particular set of responsibilities, a dharma. For example, among the Kshatriyas (the warrior caste), it was considered a sin to die in bed; dying in the battlefield was the highest honor they could aim for. In other words, dharma encouraged people of different social groups to perform their duties as best as they could.

Moksha means “liberation” or release. The eternal cycle of deaths and resurrection can be seen as a pointless repetition with no ultimate goal attached to it. Seeking permanent peace or freedom from suffering seems impossible, for sooner or later we will be reborn in worse circumstances. Moksha is the liberation from this never-ending cycle of reincarnation, a way to escape this repetition. But what would it mean to escape from this cycle? What is it that awaits the soul that manages to be released from samsara? To answer this question we need to look into the concept of atman and Brahman.

The Upanishads tell us that the core of our own self is not the body, or the mind, but atman or “ Self ”. Atman is the core of all creatures, their innermost essence. It can only be perceived by direct experience through meditation. It is when we are at the deepest level of our existence.

Brahman is the one underlying substance of the universe, the unchanging “ Absolute Being ”, the intangible essence of the entire existence. It is the undying and unchanging seed that creates and sustains everything. It is beyond all description and intellectual understanding.

One of the great insights of the Upanishads is that atman and Brahman are made of the same substance. When a person achieves moksha or liberation, atman returns to Brahman, to the source, like a drop of water returning to the ocean. The Upanishads claim that it is an illusion that we are all separate: with this realization we can be freed from ego, from reincarnation and from the suffering we experience during our existence. Moksha, in a sense, means to be reabsorbed into Brahman, into the great World Soul. (4)

The following passage explains in metaphorical terms the idea that atman and Brahman are the same:

“As the same fire assumes different shapes When it consumes objects differing in shape, So does the one Self take the shape Of every creature in whom he is present.” (Katha Upanishad II.2.9 (4) )

How is moksha achieved?

There are many ways according to the Upanishads: Meditation, introspection, and also from the knowledge that behind all forms and veils the subjective and objective are One, that we are all part of the Whole. In general, the Upanishads agree on the idea that men are naturally ignorant about the ultimate identity between atman, the self within, and Brahman. One of the goals of meditation is to achieve this identification with Brahman, and abandon the ignorance that arises from the identification with the illusory or quasi-illusory nature of the common sense world. (4)

Caste System in Ancient India

Ancient India in the Vedic Period (c. 1500—1000 BCE) did not have social stratification based on socio-economic indicators; rather, citizens were classified according to their Varna or castes. ‘Varna’ defines the hereditary roots of a newborn; it indicates the color, type, order or class of people.

Four principal categories are defined:

- Brahmins (priests, gurus, etc.)

- Kshatriyas (warriors, kings, administrators, etc.)

- Vaishyas (agriculturalists, traders, etc., also called Vysyas)

- Shudras (laborers)

Each Varna propounds specific life principles to follow; newborns are required to follow the customs, rules, conduct, and beliefs fundamental to their respective Varnas. (5)

The lowest caste was the Dalits, the untouchables, who handled meat and waste, though there is some debate over whether this class existed in antiquity. At first, it seems this caste system was merely a reflection of one’s occupation but, in time, it became more rigidly interpreted to be determined by one’s birth and one was not allowed to change castes nor to marry into a caste other than one’s own. This understanding was a reflection of the belief in an eternal order to human life dictated by a supreme deity. (6)

Purpose of the Varna System

The caste system in ancient India had been executed and acknowledged during, and ever since, the Vedic period that thrived around 1500—1000 BCE. The segregation of people based on their Varna was intended to decongest the responsibilities of one’s life, preserve the purity of a caste, and establish eternal order.

The underlying reason for adhering to Varna duties is the belief in the attainment of moksha on being dutiful. Belief in the concept of Karma reinforces the belief in the Varna life principles. As per the Vedas, it is the ideal duty of a human to seek freedom from subsequent birth and death and rid oneself of the transmigration of the soul, and this is possible when one follows the duties and principles of one’s respective Varna. According to the Vedas, consistent encroachment on others’ life responsibilities engenders an unstable society. Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras form the fourfold nature of society, each assigned appropriate life duties and ideal disposition. Men of the first three hierarchical castes are called the twice-born; first, born of their parents, and second, of their guru after the sacred thread initiation they wear over their shoulders. The Varna system is seemingly embryonic in the Vedas, later elaborated and amended in the Upanishads and Dharma Shastras. (5)

Varna System: Brahmins

Brahmins were revered as an incarnation of knowledge itself, endowed with the precepts and sermons to be discharged to all Varnas of society. They were not just revered because of their Brahmin birth but also their renunciation of worldly life and cultivation of divine qualities, assumed to be always engrossed in the contemplation of Brahman, hence called Brahmins. Priests, gurus, rishis, teachers, and scholars constituted the Brahmin community. They would always live through the Brahmacharya (celibacy) vow ordained for them. Even married Brahmins were called Brahmachari (celibate) by virtue of having intercourse only for reproducing and remaining mentally detached from the act. However, anyone from other Varnas could also become a Brahmin after extensive acquisition of knowledge and cultivation of one’s intellect.

Brahmins were the foremost choice as tutors for the newborn because they represent the link between sublime knowledge of the gods and the four Varnas. This way, since the ancestral wisdom is sustained through guru-disciple practice, all citizens born in each Varna would remain rooted to the requirements of their lives. Normally, Brahmins were the personification of contentment and dispellers of ignorance, leading all seekers to the zenith of supreme knowledge, however, under exceptions; they lived as warriors, traders, or agriculturists in severe adversity. The ones bestowed with the titles of Brahma Rishi or Maha Rishi were requested to counsel kings and their kingdoms’ administration. All Brahmin men were allowed to marry women of the first three Varnas, whereas marrying a Shudra woman would, marginally, bereft the Brahmin of his priestly status. Nevertheless, a Shudra woman would not be rejected if the Brahmin consented.

Brahmin women, contrary to the popular belief of their subordination to their husbands, were, in fact, more revered for their chastity and treated with unequalled respect. As per Manu Smriti, a Brahmin woman must only marry a Brahmin and no other, but she remains free to choose the man. She, under rare circumstances, is allowed to marry a Kshatriya or a Vaishya, but marrying a Shudra man is restricted. The restrictions in inter-caste marriages are to avoid subsequent impurity of progeny born of the matches. A man of a particular caste marrying a woman of a higher caste is considered an imperfect match, culminating in ignoble offspring. (5)

Varna System: Kshatriyas

Kshatriyas constituted the warrior clan, the kings, rulers of territories, administrators, etc. It was paramount for a Kshatriya to learn weaponry, warfare, penance, austerity, administration, moral conduct, justice, and ruling. All Kshatriyas would be sent to a Brahmin’s ashram from an early age until they became wholly equipped with requisite knowledge. Besides austerities like the Brahmins, they would gain additional knowledge of administration. Their fundamental duty was to protect their territory, defend against attacks, deliver justice, govern virtuously, and extend peace and happiness to all their subjects, and they would take counsel in matters of territorial sovereignty and ethical dilemmas from their Brahmin gurus. They were allowed to marry a woman of all Varnas with mutual consent. Although a Kshatriya or a Brahmin woman would be the first choice, Shudra women were not barred from marrying a Kshatriya.

Kshatriya women, like their male counterparts, were equipped with masculine disciplines, fully acquainted with warfare, rights to discharge duties in the king’s absence, and versed in the affairs of the kingdom. Contrary to popular belief, a Kshatriya woman was equally capable of defending a kingdom in times of distress and imparting warfare skills to her descendants. The lineage of a Kshatriya king was kept pure to ensure continuity on the throne and claim sovereignty over territories. (5)

Varna System: Vaishyas

Vaishya is the third Varna represented by agriculturalists, traders, money lenders, and those involved in commerce. Vaishyas are also the twice-born and go to the Brahmins’ ashram to learn the rules of a virtuous life and to refrain from intentional or accidental misconduct. Cattle rearing was one of the most esteemed occupations of the Vaishyas, as the possession and quality of a kingdom’s cows, elephants, horses, and their upkeep affected the quality of life and the associated prosperity of the citizens.

Vaishyas would work in close coordination with the administrators of the kingdom to discuss, implement, and constantly upgrade the living standards by providing profitable economic prospects. Because their life conduct exposes them to objects of immediate gratification, their tendency to overlook the law and despise the weak is perceived as probable. Hence, the Kshatriya king would be most busy with resolving disputes originating of conflicts among Vaishyas.

Vaishya women, too, supported their husbands in business, cattle rearing, and agriculture, and shared the burden of work. They were equally free to choose a spouse of their choice from the four Varnas, albeit selecting a Shudra was earnestly resisted. Vaishya women enjoyed protection under the law, and remarriage was undoubtedly normal, just as in the other three Varnas. A Vaishya woman had equal rights over ancestral properties in case of the untimely death of her husband, and she would be equally liable for the upbringing of her children with support from her husband. (5)

Varna System: Shudras

The last Varna represents the backbone of a prosperous economy, in which they are revered for their dutiful conduct toward life duties set out for them. Scholarly views on Shudras are the most varied since there seemingly are more restrictions on their conduct. However, Atharva Veda allows Shudras to hear and learn the Vedas by heart, and the Mahabharata, supports the inclusion of Shudras in ashrams and their learning the Vedas . Becoming officiating priests in sacrifices organized by kings was, however, to a large extent restricted. Shudras are not the twice-born, hence they are not required to wear the sacred thread like the other Varnas. A Shudra man was only allowed to marry a Shudra woman, but a Shudra woman was allowed to marry from any of the four Varnas.

Shudras would serve the Brahmins in their ashrams, Kshatriyas in their palaces and princely camps, and Vaishyas in their commercial activities. Although they are the feet of the primordial being, educated citizens of higher Varnas would always regard them as a crucial segment of society, for an orderly society would be easily compromised if the feet were weak. Shudras, on the other hand, obeyed the orders of their masters, because their knowledge of attaining moksha by embracing their prescribed duties encouraged them to remain loyal. Shudra women, too, worked as attendants and close companions of the queen and would go with her after marriage to other kingdoms. Many Shudras were also allowed to be agriculturalists, traders, and enter occupations held by Vaishyas. These detours of life duties would, however, be under special circumstances, on perceiving deteriorating economic situations. The Shudras’ selflessness makes them worthy of unprecedented regard and respect. (5)

Gradual Withdrawal from the Ancient Varna Duties

Despite the life order being arranged for all kinds of people, by the end of the Vedic period, many began to deflect and disobey their primary duties. As a large Varna populace became difficult to handle, the emergence of Jainism propounded the ideology of one single human Varna and nothing besides. Many followed the original Varna rules, but many others, disapproving opposing beliefs, formed modified sub-Varnas within the primary four Varnas. This process, occurring between 700 CE and 1500 CE, continues to this day, as India is now home to a repository of the primary four Varnas and hundreds of sub-Varnas, making the original four Varnas merely ‘umbrella terms’ and perpetually ambiguous.

The subsequent rise of Islam, Christianity, and other religions also left their mark on the original Varna system in India. Converted generations reformed their notion of Hinduism in ways that were compatible with the conditions of those times. The rise of Buddhism, too, left its significant footprint on the Varna system’s legitimate continuance in renewed conditions of life. Thus, soulful adherence to Varna duties from the peak of Vedic period eventually diminished to subjective makeshift adherence, owing partly to the discomfort in practicing Varna duties and partly to external influence. (5)

Copyright: World Religions Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Buddhism

The Three Jewels

Buddhist schools vary on the exact nature of the path to liberation, the importance and canonicity of various teachings and scriptures, and especially their respective practices. The foundations of Buddhist tradition and practice are the Three Jewels :

- The Buddha

- The Dharma (the teachings)

- The Sangha (the community)

Taking “refuge in the triple gem” has traditionally been a declaration and commitment to being on the Buddhist path, and in general distinguishes a Buddhist from a non-Buddhist.

Other practices may include following ethical precepts; support of the monastic community; renouncing conventional living and becoming a monastic; the development of mindfulness and practice of meditation; cultivation of higher wisdom and discernment; study of scriptures; devotional practices; ceremonies; and in the Mahayana tradition, invocation of buddhas and bodhisattvas. (19)

Early Years of the Buddha and the Four Sights

There is no agreement on when Siddhartha was born. This is still a question mark both in scholarship and Buddhist tradition. Several dates have been proposed, but the many contradictions and inaccuracies in the different chronologies and dating systems make it impossible to come up with a satisfactory answer free of controversy.

Modern scholarship agrees that the Buddha passed away at some point between 410 and 370 BCE, about 140-100 years before the time of Indian Emperor Ashoka’s reign (268-232 BCE). Both scholars and Buddhist tradition agree that the Buddha lived for 80 years. More exactness on this matter seems impossible.

Siddhartha’s caste was the Kshatriya caste (the warrior rulers caste). He belonged to the Sahkya clan and was born in the Gautama family. Because of this, he became to be known as Shakyamuni “sage of the Shakya clan”, which is the most common name used in the Mahayana literature to refer to the Buddha. His father was named Śuddhodana and his mother, Maya. (20)

According to this narrative, shortly after the birth of young prince Gautama, an astrologer visited the young prince’s father and prophesied that Siddhartha would either become a great king or renounce the material world to become a holy man, depending on whether he saw what life was like outside the palace walls.

Śuddhodana was determined to see his son become a king, so he prevented him from leaving the palace grounds. But at age 29, despite his father’s efforts, Gautama ventured beyond the palace several times. In a series of encounters—known in Buddhist literature as the four sights—he learned of:

- The suffering of ordinary people, encountering an old man

- A sick man

- A corpse

- An ascetic holy man, apparently content and at peace with the world

These experiences prompted Gautama to abandon royal life and take up a spiritual quest. (19)

Historical Context

After leaving Kapilavastu, Siddhartha practiced the yoga discipline under the direction of two of the leading masters of that time: Arada Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra. Siddhartha did not get the results he expected, so he left the masters, engaged in extreme asceticism, and five followers joined him. For a period of six years Siddhartha tried to attain his goal but was unsuccessful. After realizing that asceticism was not the way to attain the results he was looking for, he gave up this way of life. (21)

After eating a meal and taking a bath, Siddhartha sat down under a tree of the species ficus religiosa, where he finally attained Nirvana (perfect enlightenment) and became known as the Buddha.

Soon after this, the Buddha delivered his first sermon in a place named Sarnath, also known as the “deer park,” near the city of Varanasi. This was a key moment in the Buddhist tradition, traditionally known as the moment when the Buddha “set in motion the wheel of the law. ” The Buddha explained the middle way between asceticism and a life of luxury, the four noble truths (suffering, its origin, how to end it, and the eightfold path or the path leading to the extinction of suffering), and the impersonality of all beings.

The Buddha’s first disciples joined him around this time, and the Buddhist monastic community, known as Sangha, was established. Sariputra and Mahamaudgalyayana were the two chief disciples of the Buddha. Mahakasyapa was also an important disciple who became the convener of the First Buddhist Council. From Kapilavastu and Sravasti in the north, to Varanasi, Nalanda and many other areas in the Ganges basin, the Buddha preached his vision for about 45 years. During his career he visited his hometown, met his father, his foster mother and even his son, who joined the Sangha along with other members of the Shakya clan. Upali, another disciple of the Buddha, joined the Sangha around this time: he was a Shakya and regarded as the most competent monk in matters of monastic discipline. Ananda, a cousin of the Buddha, also became a monk; he accompanied the Buddha during the last stage of his life and persuaded him to admit women into the Sangha, thus establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha, the female Buddhist monastic community.

During his career, some kings and other rulers are described as followers of the Buddha. The Buddha’s adversary is reported to be Davadatta, his own cousin, who became a follower of the Buddha and turned out to be responsible for a schism of the Sangha, and he even tried to kill the Buddha.

The last days of the Buddha are described in detail in an ancient text named Mahaparinirvana Sutra. We are told that the Buddha visited Vaishali, where he fell ill and nearly died. Some accounts say that here the Buddha delivered his last sermon. After recovering, the Buddha travelled to Kushinagar. On his way, he accepted a meal from a smith named Cunda, which made him sick and led to his death. Once he reached Kushinagar, he encouraged his disciples to continue their activity one last time and he finally passed away. (21)

Forming of Two Separate Buddhist Lines

About a century after the death of Buddha, during the Second Buddhist Council, we find the first major schism ever recorded in Buddhism: The Mahasanghika School.

Many different schools of Buddhism had developed at that time. Buddhist tradition speaks about 18 schools of early Buddhism, although we know that there were more than that, probably around 25.

A Buddhist school named Sthaviravada (in Sanskrit “ school of the elders ”) was the most powerful of the early schools of Buddhism. Traditionally, it is held that the Mahasanghika School came into existence as a result of a dispute over monastic practice. They also seem to have emphasized the supramundane nature of the Buddha, so they were accused of preaching that the Buddha had the attributes of a god. As a result of the conflict over monastic discipline, coupled with their controversial views on the nature of the Buddha, the Mahasanghikas were expelled, thus forming two separate Buddhist lines: the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika .

During the course of several centuries, both the Sthaviravada and the Mahasanghika schools underwent many transformations, originating different schools.

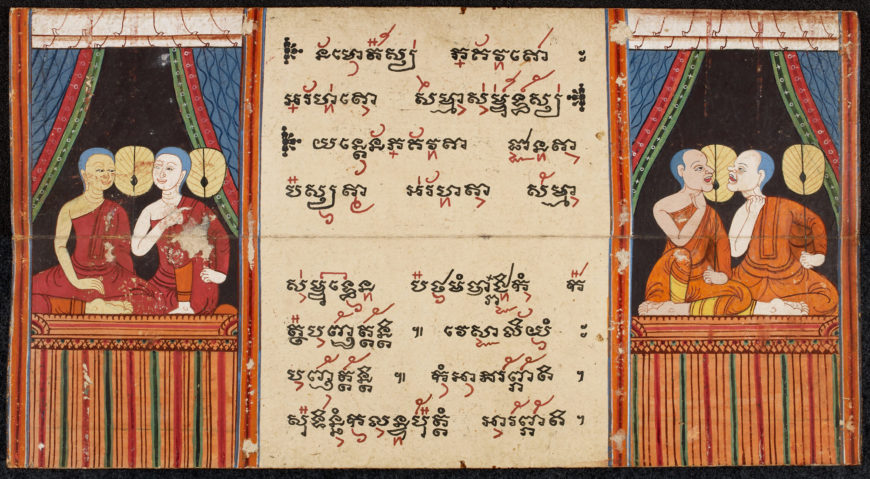

- The Theravada School, which still exists in our day, emerged from the Sthaviravada line, and is the dominant form of Buddhism in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

- The Mahasanghika School eventually disappeared as an ordination tradition.

- During the 1st century CE, while the oldest Buddhist groups were growing in south and south-east Asia, a new Buddhist school named Mahayana (“ Great Vehicle ”) originated in northern India. This school had a more adaptable approach and was open to doctrinal innovations.

- Mahayama Buddhism is today the dominant form of Buddhism in Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan, Mongolia, Korea, and Vietnam. (20)

Copyright: World Religions Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Indian Philosophy

The earliest philosophical texts in India constitute the Vedic tradition. The four Vedas are the oldest of the Hindu scriptures. They are the Rigveda, the Samaveda, the Yajurveda, and the Atharvaveda. The four Vedas were composed between 1500 and 900 BCE by the Indo-Aryan tribes that had settled in northern India. The Vedas are also called Shruti, which means “hearing” in Sanskrit. This is because for hundreds of years, the Vedas were recited orally. Hindus believe that the Vedas were divinely inspired; priests were orally transmitting the divine word through the generations.

The Rigveda is the most ancient of the four Vedic texts. The text is a collection of the “family books” of 10 clans, each of which were reluctant to part with their secret ancestral knowledge. However, when the Kuru monarchs unified these clans, they organized and codified this knowledge around 1200 BCE. The Brahmanic, or priestly, culture arose under the Kuru dynasty (Witzel 1997) and produced the three remaining Vedas. The Samaveda contains many of the Rigveda hymns but ascribes to those hymns melodies so that they can be chanted. The Yajurveda contains hymns that accompany rites of healing and other types of rituals. These two texts shine light on the history of Indo-Aryans during the Vedic period, the deities they worshipped, and their ideas about the nature of the world, its creation, and humans. The Atharvaveda incorporates rituals that reveal the daily customs and beliefs of the people, including their traditions surrounding birth and death. This text also contains philosophical speculation about the purpose of the rituals (Witzel 1997).

Classical Indian Darshanas

The word darshana derives from a Sanskrit word meaning “to view.” In Hindu philosophy, darshana refers to the beholding of a god, a holy person, or a sacred object. This experience is reciprocal: the religious believer beholds the deity and is beheld by the deity in turn. Those who behold the sacred are blessed by this encounter. The term darshana is also used to refer to six classical schools of thought based on views or manifestations of the divine—six ways of seeing and being seen by the divine. The six principal orthodox Hindu darshanas are Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa, and Vedanta. Non-Hindu or heterodox darshanas include Buddhism and Jainism.

Samkhya

Samkhya is a dualistic school of philosophy that holds that everything is composed of purusha (pure, absolute consciousness) and prakriti (matter). An evolutionary process gets underway when purusha comes into contact with prakriti. These admixtures of mind and matter produce more or less pure things such as the human mind, the five senses, the intellect, and the ego as well as various manifestations of material things. Living beings occur when purusha and prakriti bond together. Liberation finally occurs when mind is freed from the bondage of matter.

Western readers should take care not to reduce Samkhya’s metaphysics and epistemology to the various dualistic systems seen in, for example, the account of the soul in Plato’s Phaedo or in Christian metaphysics more generally. The metaphysical system of creation in Samkhya is much more complex than either of these Western examples.

When purusha first focuses on prakriti, buddhi, or spiritual awareness, results. Spiritual awareness gives rise to the individualized ego or I-consciousness that creates five gross elements (space, air, earth, fire, water) and then five fine elements (sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste). These in turn give rise to the five sense organs, the five organs of activity (used to speak, grasp, move, procreate, and evacuate), and the mind that coordinates them.

LITERATURE

Hindu Literature

The Bhagavad Gita is a part of the Mahabharata. At the beginning of the Gita, Arjuna is confronted with the moral decision of regaining his kingdom knowing full well that friends, teachers, and relatives will lose their lives. Krishna, the incarnation of the god Vishnu and Brahman, disguises himself as Arjuna’s charioteer and offers his guidance to Arjuna. Krishna’s advice is based on the relation between the individual-self and Atman (the ultimate Self) and the relation between nature and Brahman (ultimate reality). Indeed, as Krishna explains, Atman is Brahman. Krishna further traces out the various paths to ultimate knowledge and the consequent realization of Atman for the individual. Different paths or yogas are shown to be appropriate for different psychological types—personalities predisposed to intellect, action, devotion, or meditation.

Read an English translation of “The Bhagavad Gita” from Readings in Eastern Philosophy: An Open Source Text (The Reading Selection from Bhagavad Gita (lander.edu))

Read an English translation of more Hindu texts from Reading in Eastern Philosophy: An Open Source Text

Buddhist Literature

After his enlightenment, Buddha elucidated the “Four Noble Truths” in his first instruction to his disciples; briefly stated, these truths explain how (1) all who live suffer, (2) suffering is a result of self, (3) suffering can be avoided, and (4) suffering can be extinguished by the “Eightfold Path.” The reading selection after this one continues Carus’ compilation of Buddha’s teaching with the “Eightfold Path.”

Read an English translation of “The Four Noble Truths” from Reading in Eastern Philosophy: An Open Source Text (https://philosophy.lander.edu/oriental/reader/reader/c1479.html)

Read an English translation of more Buddhist texts from Reading in Eastern Philosophy: An Open Source Text (https://philosophy.lander.edu/oriental/reader/reader/book1.html)

ARCHITECTURE

Hindu Temples

Video URL: https://youtu.be/o7-i6KLoEkc?si=X0hImd3SU2Z1vmSO

Copyright: Asian Art Museum, “Hindu temples,” in Smarthistory, January 29, 2016, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hindu-temples/.

Buddhist Monasteries

In the early years of Buddhism, following the practices of contemporary religions such as Hinduism and Jainism (and other faiths that no longer exist), monks dedicated themselves to an ascetic life (a practice of self-denial particular to the pursuit of religious or spiritual goals) wandering the country with no permanent living quarters. They were fed, clothed, and housed in inclement weather by people wishing to gain merit, which is a spiritual credit earned through virtuous acts. Eventually monastic complexes were created for the monks close enough to a town in order to receive alms or charity from the villagers, but far enough away so as not to be disturbed during meditation.

Three types of architecture: stupa, vihara and the chaitya

Buddhism, the first Indian religion to require large communal and monastic spaces, inspired three types of architecture.

The first was the stupa, a significant object in Buddhist art and architecture. On a very basic level it is a burial mound for the Buddha. The original stupas contained the Buddha’s ashes. Relics are objects associated with an esteemed person, including that person’s bones (or ashes in the case of the Buddha), or things the person used or had worn. The veneration, or respect, for relics is prevalent in many religious faiths, particularly in Christianity. By the time the Buddhist monasteries gained importance, the stupas were empty of these relics and simply became symbols of the Buddha and the Buddhist ideology.

Second was the construction of the vihara, a Buddhist monastery that also contained a residence hall for the monks.

Third was the chaitya, an assembly hall that contained a stupa (though one empty of relics). This became an important feature for the monasteries that were cut into cliffs in central India. The central hall of the chaitya was arranged to allow for circumambulation of the stupa.

The stupa is at the end of the nave (the main central aisle), as seen in the photo above. On either side of the columns are side aisles to help people walk through the space—around to the stupa, and back out. This is similar to the architecture of Early Christianity (for example, the side aisles at the Early Christian Church in Rome, Santa Sabina, which help the flow of people who come to worship at the altar at the end of the nave).

Buddhist Monasteries in India

In India, by the 1st century, many monasteries were founded as learning centers on sites already associated with Buddha and Buddhism. These sites include Lumbini where the Buddha was born, Bodh Gaya where he achieved enlightenment and the knowledge of the dharma (the Four Noble Truths), Sarnath (Deer Park) where he preached his first sermon sharing the dharma, and Kushingara where he died.

Ashoka: the first King to embrace Buddhism

Sites special to King Ashoka (304–232 B.C.E.), the first king (of northern India) to embrace Buddhism, were also integral to the building of monasteries. For example, the complex at Sanchi, where the original Great Stupa (Mahastupa) of Sanchi was created as a reliquary for the Buddha’s ashes after his death, became the largest of many stupas that were created later when a monastery was built at the site. Ashoka added one of his famous pillars at this location—pillars that not only proclaimed his acceptance of Buddhism, but also served as instructional objects on Buddhist ideology.

Between 120 BCE and 200 C.E. over 1000 viharas (a monastery with residence hall for the monks), and chaityas (a stupa monument hall), were established along ancient and prosperous trade routes. The monasteries required large living areas.

A vihara was a dwelling of one or two stories, fronted by a pillared veranda. The monks’ or nuns’ cells were arranged around a central meeting hall as in the plan of the Ajanta vihara (left). Each cell contained a stone bed, a pillow and a niche for a lamp.

The monastery quickly became important and had a three-fold purpose: as a residence for monks, as a center for religious work (on behalf of the laity) and as a center for Buddhist learning. During Ashoka’s reign in the 3rd century B.C.E., the Mahabodhi Temple (the Great Temple of Enlightenment where Buddha achieved his knowledge of the dharma—the Four Noble Truths) was built in Bodh Gaya, currently in the Indian state of Bihar in northern India. It contained a monastery and shrine. In order to acknowledge the exact site where the Buddha attained Enlightenment, Ashoka built a diamond throne (vajrasana – literally diamond seat) underscoring the indestructible path of the dharma.

Rock-cut caves

The rock-cut caves were established in the 3rd century B.C.E. in the western Deccan Plateau, which makes up most of the southern portion of India. The earliest rock-cut monastic centers include the Bhaja Caves, the Karle Caves and the Ajanta Caves.

The objects found in the caves suggest a profitable relationship existed between the monks and wealthy traders. The Bhaja caves were located on a major trade route from the Arabian Sea eastward toward the Deccan region linking north and south India. Merchants, wealthy from the trade between the Roman Empire and southeast Asia, often sponsored architectural additions including pillars, arches, reliefs and façades to the caves. Buddhist monks, serving as missionaries, often accompanied traders throughout India, up into Nepal and Tibet, spreading the dharma as they travelled.

Bhaja

At Bhaja there are no representations of the Buddha other than the stupa since Bhaja was an active monastery during the earliest phase of Buddhism, Hinayana (lesser vehicle), when no images of the Buddha were created. In Hinayana, the memory of the historical Buddha and his teachings were still a very real part of the practice. The Buddha himself did not encourage worship of him (something images would encourage), but desired that the practitioner focus on the dharma (the law, the Four Noble Truths).

The main chaitya hall (which contained a memorial stupa, empty of relics, above) at Bhaja contains a solid stone stupa in the nave flanked by two side aisles. It is the earliest example of this type of rock-cut cave and closely resembles the wooden structures that preceded it. The columns slope inwards, which would have been necessary in the early wooden structures in the north of India in order to support the outward thrust from the top of the vault. In similar stone caves, sometimes the columns are placed in stone pots, which mimic the stone pots the wooden columns were positioned in, in order to thwart termites. This is an example of a practical architectural practice being adopted as the standard.

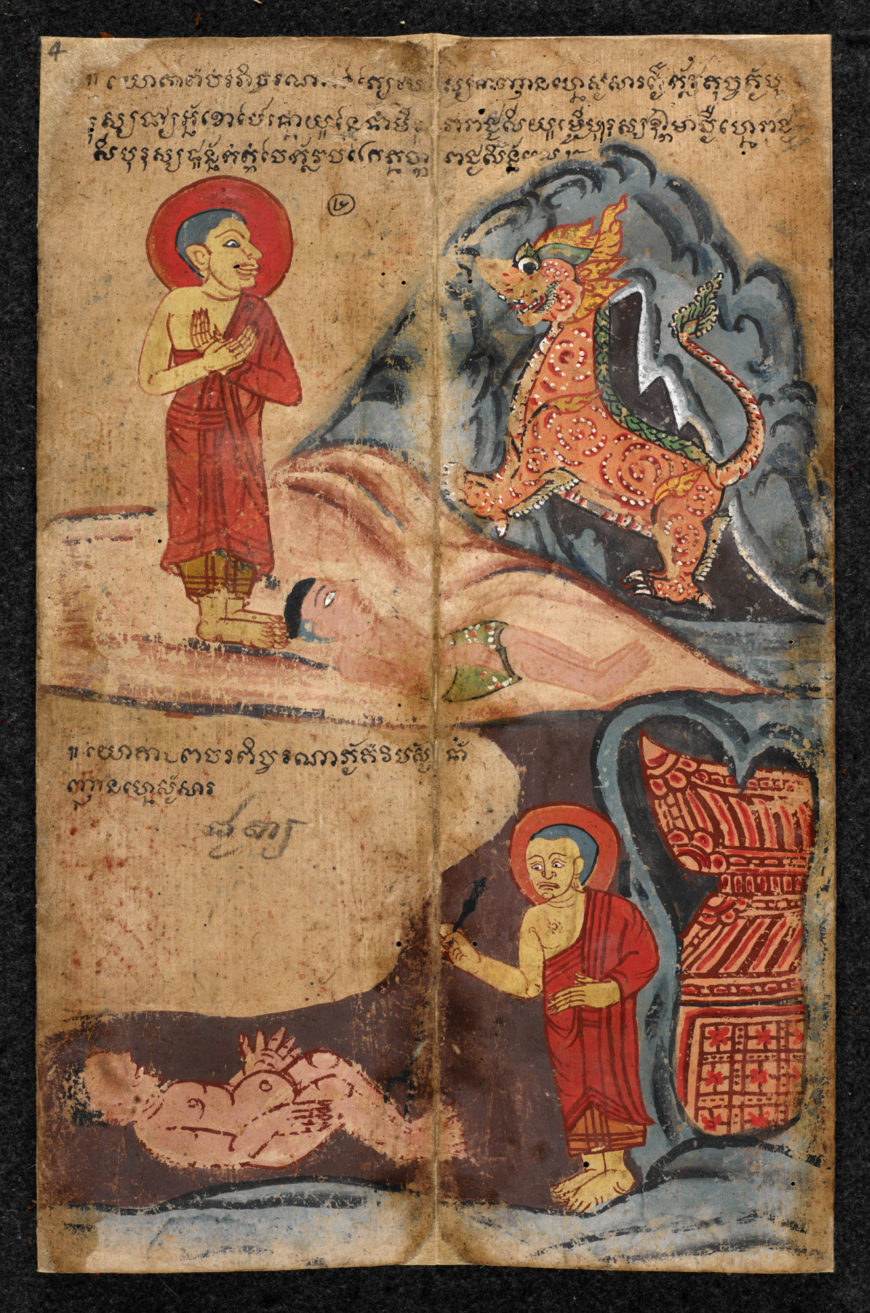

Ajanta

At Ajanta, the earliest phase of construction also belongs to the Hinayana (lesser vehicle) phase of Buddhism (in which no human image of the Buddha was created). The caves are very similar to those at Bhaja. During the second phase of construction, Buddhism was in the Mahayana (greater vehicle) phase and images of the Buddha, predominantly drawn from the jataka stories—the life stories of the Buddha—were painted throughout. In Mahayana, which was more distant in time from the life of the Buddha, there was a need for physical reminders of the Buddha and his teachings. Thus images of the Buddha performing his Enlightenment and his first sermon (when he shared the Four Noble Truths with the laity) proliferated. The paintings at Ajanta provide some of the earliest and finest examples of Buddhist painting from the period. The images also provide documentation of contemporary events and social custom under Gupta reign (320-550 C.E.).

Rock-cut monasteries become more complex

Eventually, the rock-cut monasteries became quite complex. They consisted of several stories with inner courtyards and veranda. Some facades had reliefs, images projecting from the stone, of the Buddha and other deities. A stupa was still placed in the central hall, but now an image of the Buddha was carved into it, underscoring that the Buddha is the stupa. Stories from the Buddha’s life were also, at times, added to the interior in both paintings and reliefs.

Copyright: : Dr. Karen Shelby, “Buddhist monasteries,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed April 9, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/buddhist-monasteries/.

PERFORMING ARTS

Buddhist Meditation and Chant

Some key acts of Buddhist practice are meditation and chanting. They are a continuation of the teachings of the Buddha, in that they are both felt to bring peace and fulfilment, and help us to lead happier lives. You might have seen a Buddha image, and noticed the sense of reassurance and stability it offers. These are the qualities meditation can arouse in us. Chant is considered helpful by some to strengthen these qualities too.

Buddhist meditation generally takes a simple object, often the breath, and offer techniques to practice mindfulness and arouse awareness with it. This brings peace and ease with the way the breath rises and falls. If we feel some stillness and happiness in the breath, we can feel peaceful and unified during the day too. The breath arouses calm, as it becomes very unifying and pleasant to be aware of it; the meditator can then develop jhāna. The breath also arouses insight, as the mind feels at ease in its constant ebb and flow, and sees impermanence in the breath’s movement in and out of the body. When both calm and insight are present, the meditation is in balance. The texts describe many such meditations, of different varieties. Loving kindness (mettā-bhāvanā), for instance, is a popular calm practice linked to mindfulness that helps you to feel comfortable with yourself, and others around. In this meditation you wish for your own happiness, and all other beings too. If you are kind to yourself, you are more likely to find it easier to feel kindness for others.

These meditations work with the three ethical factors of speech, action and livelihood. They are said to protect the mind in daily life, and are important as a basis for all meditation.

What is Buddhist chanting?

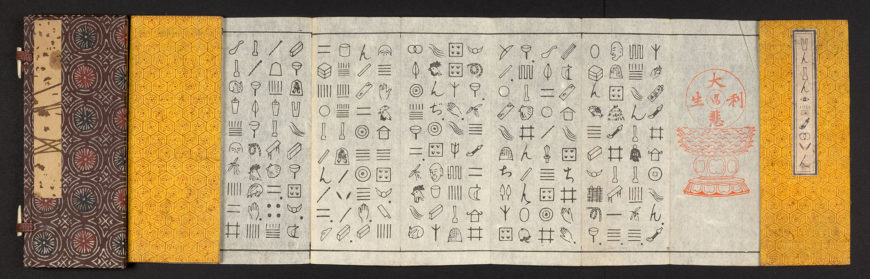

Such images were and are used as objects of devotion. The person sitting or kneeling in front of them makes offerings of flowers, lights and incense, and meditates or chants. This is a way of paying homage, honouring, and hoping that the qualities in the image might arise in them too. The Buddha represents the human mind at its full potential, with great understanding, calm and a profound wisdom. Buddhism suggests that this awakened wisdom and peace is possible in all human beings too, but needs to be cultivated, or found. Just by sitting in front of the figure, and paying respects to it, Buddhists, or sometimes those just interested in Buddhism, can also feel intuitively a connection with the Buddhist path and the way to freedom. So some meditations are chants, refuges to the Buddha, to his teaching, and to his followers. There are also longer chants, called ‘recollections’ (anusṃrti/anussati), reflections on the possibilities of an awake mind, the teaching that can bring this, and other beings who have followed and teach the path to freedom.

The chants introduce meaning and purpose into one’s life, and are often communal. Anyone, anywhere, can sense connectedness with the Buddhist path; chanting settles the mind to enter meditation, or to feel part of a larger group in a temple. Some chants remembering the qualities of the Buddha are used in daily life too, outside the temple. In this way Buddhists can chant a simple recollection of the Buddha, while working, or going about their daily lives. They feel that everything they do is thus changed by this. If the chant becomes natural, they feel they might be reborn in a Pure Land, a heaven realm on the way to liberation. Some practitioners say that such a heaven is the mind itself, when it is free from distractions and problems.

Most Buddhists chant to help their daily life. Many people take the ‘refuges’, the protection of the Buddha, the teaching (dhamma), and the community of followers (sangha). They often commit to the five precepts too: undertakings not to harm others, not to steal, not to use the body for sexual activity that can harm self and others, not to lie, and not to become intoxicated. These support the ethical part of the eightfold path: right speech, action and livelihood. Following the precepts ensures the path is whole; they are seen as protective, so meditation and daily life will be safe and not cause harm or worry. All forms of Buddhism regard them as important.

What is Zazen meditation?

Yet another form of meditation takes everything that is going on, and sits with it, coming to understanding through watching processes in the mind and body, sounds, touches, changing feelings. This kind of meditation is known as Zazen, and is practiced by some schools of Buddhism from China, Korea and Japan.

As this summary suggests, there are many kinds of Buddhist meditations. All aim to balance us, and bring calm and insight. In early texts, the Buddha taught those that suited a particular person, and adapted it to their needs. Effective meditation practices do this now, and make sure that the practice suits the person, and that they are ready for each new stage as it comes along. All aspects of the eightfold path are important; all support one another and depend upon one another.

The British Library, “Buddhist meditation and chant,” in Smarthistory, March 9, 2021, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/buddhist-meditation-and-chant/.

Sanskrit Theater

VISUAL ARTS

Hindu Deities in Art

One of the most striking features of Hinduism is the seemingly endless array of images of gods and goddesses, most with animal associates, that inhabit the colourful temples, and wayside shrines and homes of its adherents. Because of this, Hinduism has been called an idolatrous and polytheistic religion.

Hinduism can be likened to an enormous banyan tree extending itself through many centres of belief and practice which can be seen to link up with each other in various ways, like a great network that is one, yet many. The concepts of deity, worship and pilgrimage in Hinduism are a prime example of this ‘polycentric’ phenomenon.

What does the Veda say about deities?

Deities are a key feature of Hindu sacred texts. The Vedic texts describe many so-called gods and goddesses (devas and devīs) who personify various cosmic powers through fire, wind, sun, dawn, darkness, earth and so on. There is no firm evidence that these Vedic deities were worshipped by images; rather, they were summoned through the sacrificial ritual (yajña), with the deity Agni (fire) generally acting as intermediary, to bestow various boons to their supplicants on earth in exchange for homage and the ritual offering. Some Vedic texts speak of a One that seemed to undergird the plurality of these devas and devīs as their support and origin. In time, in the Upaniṣads, this One (Brahman) was envisaged as either the transcendent, supra-personal source of all change and differentiation in our world which would eventually dissolve back into the One, or as the supreme, personal Lord (īśvara) who was the mainstay and goal of all finite being. In both conceptions, we have the basis for subsequent notions of a transcendent reality that is accessible to humans by meditation and/or prayer and worship.

When did personal gods develop in Hinduism?

It is in the Bhagavad Gītā, composed at about the beginning of the Common Era, that we first find sustained textual evidence of developed thinking about devotional faith in a personal God, named Krishna (also spelt Kṛṣṇa). In this text, Krishna teaches his friend and disciple, Arjuna, about his divine nature and relationship with the world, and how the devoted soul can find liberation (mokṣa) from the sorrows and limitations of life through loving communion with him. Here, also for the first time in Hinduism, we encounter the doctrine of the avatāra (anglicised as avatar), which teaches that the Supreme Being descends periodically into the world in embodied form for, according to the Gītā, ‘re-establishing dharma, protecting the virtuous and destroying the wicked.’ The doctrine of multiple avatars with their specific objectives was to develop subsequently over the centuries in various sacred texts, such as the Purāṇas.

At about the same time as the Gītā was composed, the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad endorses devotion to Shiva (also spelt Śiva), also called Rudra, as the Supreme Being who transforms his devotees from the halter (pāśa) of existence into a state of profound union with him. Both the Gītā and the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad proclaim a form of disciplined devotion (bhakti) as the means to salvation, and it was not till about the 5th century that a theology of saving devotion to the Great Goddess (Mahādevī) appeared in the Devī Māhātmya. In a manner that accounts for the devotional faith of most Hindus, each of these three deities, Vishnu (also spelt Viṣṇu), Shiva, and the Goddess, under one alternative name or other, can be seen to head a distinctive strand of theistic Hinduism which inter-relates in complex ways with the other two. In terms of this interlocking grid, most Hindus would have a firm sense of religious belonging through faith in a Supreme Deity who can be approached, understood and worshipped by way of a system of disciplined belief and practice.

Is Hinduism a polytheistic religion?

It is important to grasp the distinctive way Hindus tend to approach their desired deity (iṣṭadevatā), usually a traditional feature of household or community worship, as the focus of their religious life. This deity, be it a form of Shiva, Vishnu or the Goddess, can normally manifest through multiple forms (rūpa). When speaking of worship of the great Goddess, the Kālikā Purāṇa (14th century) conveniently gives the model for the relationship between the chosen deity and its various forms: ‘Just as rays of the sun continually come forth from the sun’s disc so [the various forms of the Goddess] come forth from the body of the Goddess.’ This idea seems to be a conceptual development of the Vedic notion of the underlying One manifesting in and through the many: there is, ultimately, only one Supreme Source which can manifest, like rays of the sun, in alternative forms, each of which may indeed have its own tradition of narrative, belief and worship, but only as inter-linking with other centres of the whole. We can hardly call this ‘polytheism’ in the common sense of the term; it is, rather, a distinctive kind of ‘polymorphic’ monotheism, i.e. a monotheism underlying many manifestations of the same Deity – the whole relational web being a prime example of Hindu polycentrism at work.

When did the worship of deities begin?

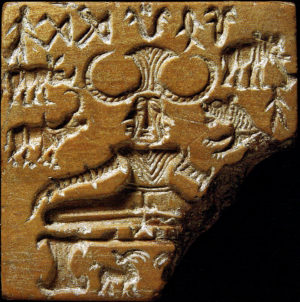

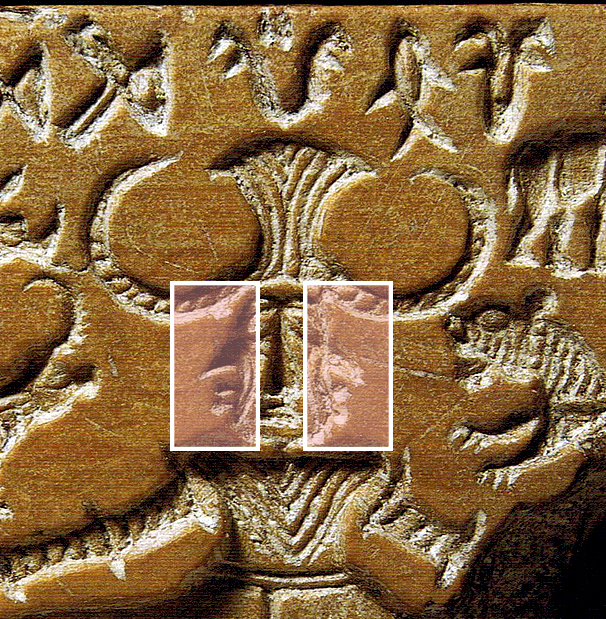

The first archaeological evidence we have of standing temple construction and its implication of image-worship of the deity occurs in about the 3rd century BCE – of a Vishnu temple (in eastern Rajasthan) and of a Shiva temple not too far away. Presumably, since these were constructions of mud, timber, brick, stone etc., the process of temple-building had begun appreciably earlier, though we cannot say exactly where or when. We can also assume from textual and archaeological evidence that image-worship in Hinduism was present by about the 6th to the 5th century BCE.

It is generally believed (though there is mounting evidence against some external ‘Aryan invasion’) that people known as ancient Aryans had originally displaced an advanced civilisation in the north-western regions of the subcontinent called the Indus civilisation. Thre is evidence of brick structures, dating from this civilisation, that indicate a religious purpose and of small figures made of, and in, firm material such as terracotta and soapstone. However, since there is no agreement about how to interpret the script of the Indus civilisation, we cannot say for sure that these were truly figures of religious import, and thus had an influence on the fashioning later Hindu images.

How are deities worshiped?

By the first centuries of the Common Era, cults of the worship of images of various deities, such as Vishnu and the Goddess, were established. Such worship (pūjā) would have taken place both at home and in the temple. In time, temple design became ornate and varied, and temple-worship involved making the image according to strict iconographic rules and served by a dedicated class of priests, an elaborate ritual of consecration of the image, flower and food offerings, anointing and bathing the image, oil lamps, incense, bells and processions with the image, a daily programme for the deities involved patterned on practices of the royal court, and so on.

Most deities have an animal associate (vāhana) which helps identify the deity and express the latter’s specific powers; this was achieved too by an artistic device that attributed multiple body-parts, such as hands and heads, adorned by weapons and other objects, to the image. There are many stories, especially in the Purāṇas, which describe the origin and role of the vāhana and the weapons and other attributes associated with the image.

The temple itself was viewed as the body of the deity, with the darkened chamber at its heart in which (the image of) the deity was placed, known as the garbha-gṛha or ‘womb-house.’ This was the place in which the worshipper, who approached as humble supplicant, was reborn to a new lease of life by the grace of the deity.

Hindus tend to perceive the material of the consecrated image (arcā) as having undergone substantial change in the multiple earthly bodies of the deity itself, whose true, transcendent nature is really one and spiritual, consisting of pure consciousness, power and bliss. Here too we see that a complex relationship obtains between the One and the many. This cannot be dubbed ‘idolatry’ in any usually understood, derogatory sense. The point of the transcendent deity’s manifesting as the arcā, of appearing limited and powerless in many forms and places, is to express compassionate love and accessibility (saulabhya) on the deity’s part for the sake of the worshipper. Otherwise, as the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa (ca. 6th–7th century) says, ‘what [else] can the image accomplish for the One who is always fulfilled?’ ‘Understand’, continues the Purāṇa, ‘that the purpose of His image-worship is the love of the worshipper’, that is, the divine love for the worshipper and the worshipper’s love for God.

Other than by forms of temple worship, which include both personal prayer and various rituals conducted by priests, the deity may be worshipped at home too, either through personal images, or family images handed down, or by way of meditation (dhyāna). Dhyāna can include highly specialised kinds of visualisation of the deity invoked, in which the deity is often envisaged as communicating with the worshipper.

Another form of worshipping the deity in Hinduism is through pilgrimage (yātrā). Pilgrimage is a way of creating a sacred landscape, of indicating that the whole world, including the pilgrim, belongs to the deity and is under its rulership. Through every pilgrimage, Hindus encounter a tīrtha, a sacred ford or crossing-point between heaven and earth, by which they may come to terms with this world of sorrows and arrive at the threshold of liberation. Over time, a great many tīrthas have developed across the Hindu sacred landscape.

The British Library, “Hindu deities,” in Smarthistory, March 5, 2021, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/hindu-deities/.

Representations of Krishna

Lord Krishna is an important figure in the Hindu pantheon who appears often in works of art and architecture. Krishna is one of the many avatars (forms or manifestations) of the Hindu god Vishnu, who according to devotees was born on earth to create balance and harmony in the universe. Intense personal devotion (called bhakti) for Krishna continues to be important for many Hindus around the world and is the subject of numerous works of art, from very early representations to the present.

Krishna appears in anthropomorphic (human-like) form, as a male figure with blue-colored skin. He often wears a yellow- or orange-colored hip wrapper and a crown ornamented with peacock feathers. He is powerful, mischievous, fun-loving, flirtatious, and the subject of great adoration. Representations of Krishna appear throughout architecture, paintings, sculpture, and textiles in many parts of the Indian subcontinent. Stories about Krishna are also the subject of numerous important religious texts including the Bhagavata Purana and the Gita Govinda. Krishna also assumes the role of the charioteer for the hero Arjuna in the epic story The Mahabharata, and the conversation about dharma (duty or laws of conduct) that occurs between these two figures during a pause in battle is the foundation for the famous poem the Bhagavad Gita.

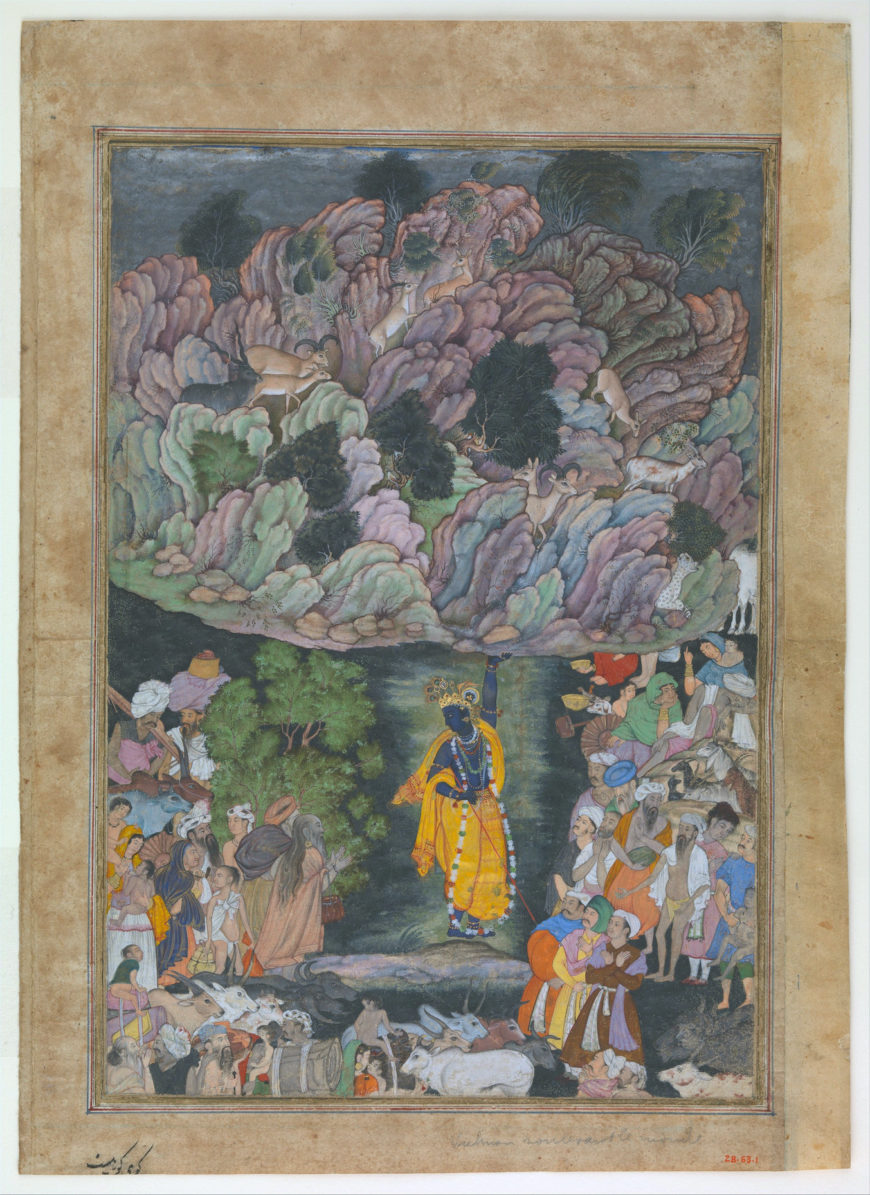

Krishna and Mount Govardhana

A 13th-century carving from the Hoysalesvara Temple at Halebidu in southern India shows an episode in the life of Krishna in which the landscape is once-again a central character. In this depiction Krishna stands in a triple-bend posture which creates an elegant swaying of his body (tribhanga). One of the many postures connected to traditional forms of Indian dance, depicting figures in tribhanga (with alternating bends at the knees, hips / waist, and shoulders / neck) was one way for artists in South Asia to create a sense of movement and dynamism in representations of the body. We can see tribhanga postures used in many different ways throughout South Asian art, both as a subtle sway (as in the Krishna sculpture above) or in an exaggerated form as in Shiva Nataraja (Lord of the Dance). Krishna here is beautifully adorned with jewelry and a conical headdress. Surrounding him on all sides are animals (especially cows which are significant to Krishna as he was raised in Brindavan as a cow herder) and human figures. Most notably, the artist depicts Krishna’s left arm raised above his head, holding up what appears to be a mountain full of plants and animals. The mountain in this scene is Mount Govardhana, also called Govardhana Hill, which is close to Brindavan and in the region of Braj.

The story goes that as a young boy, Krishna noticed the people of Braj spending too much time and energy preparing sacrifices to appease the god Indra, who is the Hindu god of the heavens and also of lightning, storms, and thunder. As a result, the people’s farms and livestock were neglected. Krishna reminded the people of Braj of their duty (dharma) to care for their land and animals and suggested instead that they cease the elaborate rituals and sacrifices for Indra. Indra became angered by this and as retribution sent an enormous storm that began to flood the entire region. In response to Indra’s tempest, Krishna lifted up a nearby mountain, Mount Govardhana, and used it as an umbrella to protect the people of Braj.

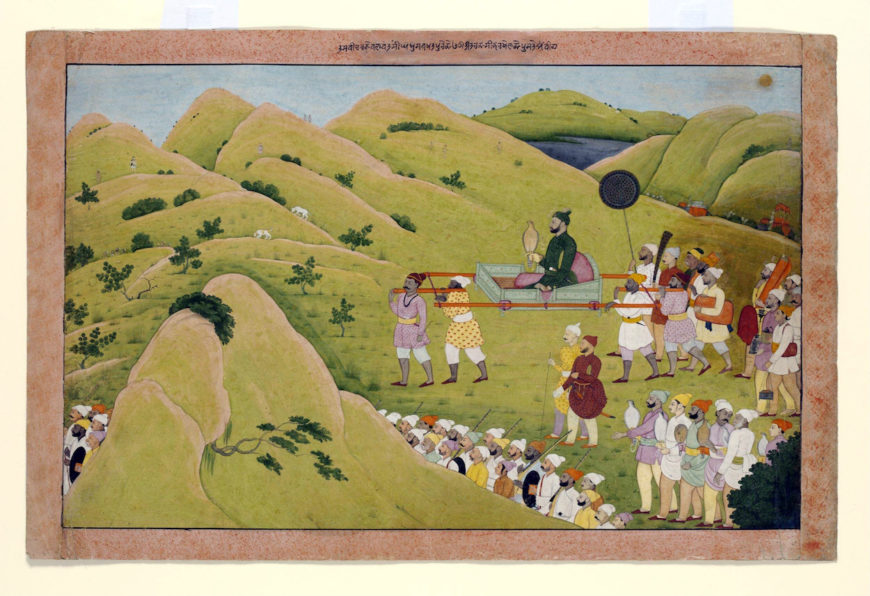

The story of Krishna lifting Mount Govardhana is a popular subject for works of art. A fantastic depiction of this story appears in a Mughal-period painting and shows Krishna at the center of the composition lifting the mountain, which is full of stylized rocks, trees, and animals. The grateful residents of Braj, including both human figures and numerous cows, surround Krishna on all sides and appear safely protected from the tumultuous sky (representing Indra’s storm) at the very top of the scene. The artist of this painting renders the villagers of Braj in dynamic postures and with great diversity. Some figures appear fully dressed in Mughal court attire while others wear only simple loin cloths more typical of Hindu ascetics. Children latch on to the bodies’ of their mothers and playfully ride cows. Some of the villagers turn their attention toward Krishna as if to offer their praise and gratitude, while others appear to be conversing amongst themselves almost unaware of the blue-skinned god’s miraculous feat.

Depictions of Krishna lifting Mount Govardhana are most iconic amongst the Pushtimarg sect of Vaishnavite devotees, who worship this form of Krishna (known as Shri Nathji to the Pushtimarg) at their temple in Nathdwara, Rajasthan. In many depictions of Shri Nathji, such as this 19th-century painting, the mountain itself is absent from the composition, though it is implied by Krishna’s raised arm.

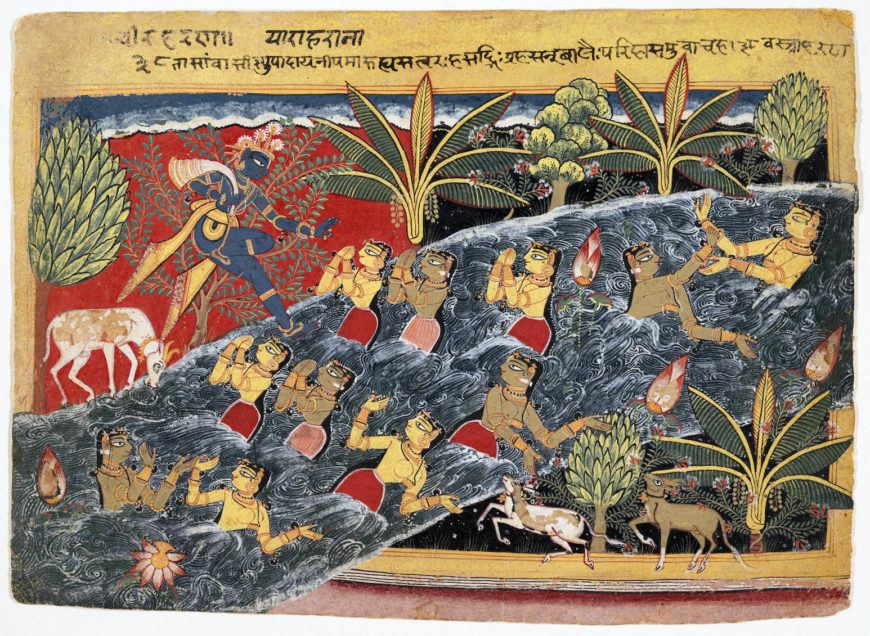

Krishna and the Gopis

Another well-known story from the life of Krishna that appears often in works of art is the episode when he stole clothing from the milkmaids (gopis) who were bathing in the nearby Yamuna River. In this 16th-century folio from a Bhagavata Purana manuscript, we see the gopis standing partially nude amongst the swirling waves of the Yamuna. Some of them appear with their hands together in anjali mudra (a gesture of prayer) as if begging Krishna to return their clothing. Others appear to be content frolicking and splashing amongst the waves. Textual versions of the Bhagavata Purana describe Krishna as playfully chastising the gopis for wading, half-naked, into the water (and exposing themselves to the god of waters, Varuna) moments after they prayed for Krishna to become their husband. Some of the gopis beg Krishna to forgive their immodesty, which he laughingly bestows (he was, in fact, jesting all along!). In this image, the river, which bisects the composition and runs beyond the margins of the picture, is a main character of the story.

This iconic episode also inspired an oil painting by the well-known modern artist Francis Newton Souza, a founding member of the Progressive Artists’ Group of Bombay, who depicts the body of Krishna through a thick application of teal-colored paint that seems to merge with the tree in which he is standing. The figure of Krishna continues to be a source of inspiration for many artists living and working in South Asia today, and can serve as a potent subject of spiritual reverence and devotion, a symbol of philosophical beliefs, and/or a vehicle for social and political critique.

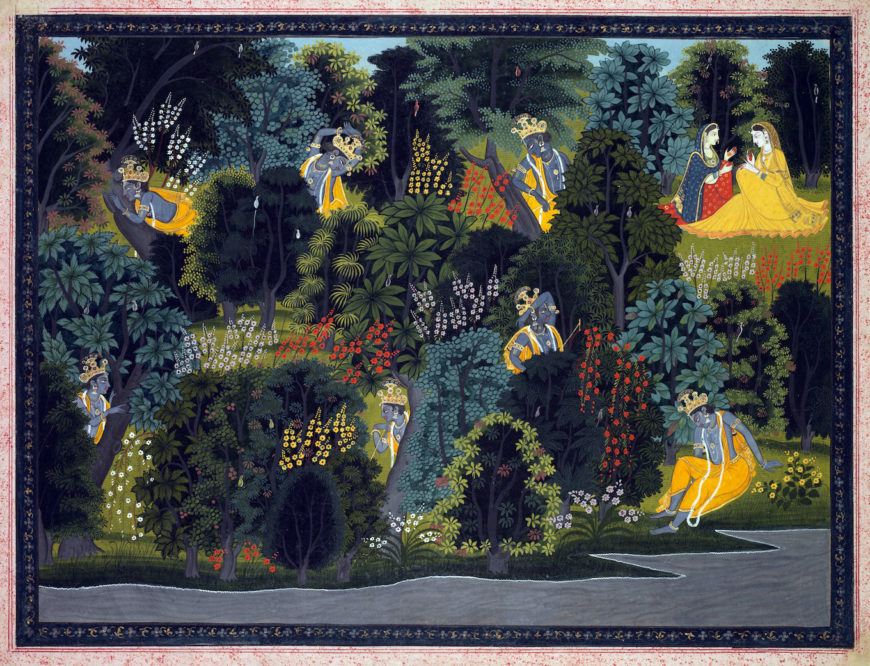

Krishna and Radha

Most beloved amongst the gopis is Radha, the consort of Krishna and considered by many devotees to be a goddess in her own right (specifically, an avatar of the goddess Lakshmi). An important early text, the Gita Govinda, composed by the writer Jayadeva in the 12th century, describes in poetic verse the loving, and sometimes contentious, relationship between Krishna and Radha. Radha sings,

I followed [Krishna] at night to depths of the forest.

He pierced my heart with arrows of love.…

The sweet spring night torments my loneliness—

Some other girl now enjoys [Krishna’s] favor.

A series of paintings from the Pahari region visualize aspects of this relationship. In this painting, Krishna appears multiple times in the composition as if he is moving throughout the forest, waiting anxiously for Radha to appear. Radha sits in the upper right corner of the composition (in yellow) and speaks with her friend and confidante about whether or not she should meet Krishna. Radha is already married to another man and also knows of Krishna’s tendency to flirt with other gopis, which inspires jealousy within her and fuels her apprehension. Radha’s friend sings,

[Krishna] comes when spring winds, bearing honey, blow.

What greater pleasure exists in the world, friend?…

How often must I repeat the refrain?

Don’t recoil when [Krishna] longs to charm you!…

Why conjure heavy despair in your heart?

Listen to me tell how he regrets betraying you.

One interpretation of the religious meaning of this painting is that it is a metaphor for how divine insight is available and waiting for humans, who need only to release themselves from the lure of the material world and its social conventions. In such depictions, the metaphor of profane love (the love between Krishna and Radha for example) is often used to describe sacred love or union with the divine.

In another painting from the same Gita Govinda series, Radha (now dressed in bright orange and gold) is once again speaking with her female confidante as Krishna prepares a bed of leaves in the forest nearby for a tryst with Radha. At the center of this composition, the artist depicts Krishna a second time as if to suggest he is spying on Radha as he eagerly awaits their union.

A third painting in this series shows Krishna seated on the bed of leaves, still waiting for Radha, but now playing music on his flute—an instrument closely connected to the god and in some cases considered a metaphor for the devotee’s union with the divine. In this painting, the sky is darker, suggesting that night is beginning to fall. Flowers on several of the trees seem to have burst into bloom as if filling the air with sweet fragrance. The blossoming forest and the darkening sky create a mood that seems to call to Radha, like the flute, and echoes Krishna’s desire to be with her.

All [Krishna’s] deep-locked emotions broke when he saw Radha’s face,

Like sea waves cresting when the full moon appears.…

The soft black curve of his body was wrapped in fine silk cloth,

Like a dark lotus root wrapped in veils of yellow pollen.…

Flowers tangled his hair like moonbeams caught in cloudbreaks.

His sandal browmark was the moon’s circle rising in darkness.…

Jayadeva’s singing doubles the power of Krishna’s adornments.

Worship [Krishna] in your heart and consummate his favor!

Copyright: Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi, “Representations of Krishna,” in Smarthistory, July 25, 2021, accessed April 10, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/representations-krishna/.

Buddhist Sculpture

Video URL: https://youtu.be/jl6S0wdeWk4?si=npwisX7lZ0B8RC6M

Copyright: Asian Art Museum, “Beliefs made visible: Buddhist art in South Asia,” in Smarthistory, January 27, 2016, accessed April 9, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/beliefs-made-visible-buddhist-art-in-south-asia/.

The fifth and fourth centuries B.C. were a time of worldwide intellectual ferment. It was an age of great thinkers, such as Socrates and Plato, Confucius and Laozi. In India, it was the age of the Buddha, after whose death a religion developed that eventually spread far beyond its homeland.

Siddhartha, the prince who was to become the Buddha, was born into the royal family of Kapilavastu, a small kingdom in the Himalayan foothills. His was a divine conception and miraculous birth, at which sages predicted that he would become a universal conqueror, either of the physical world or of men’s minds. It was the latter conquest that came to pass. Giving up the pleasures of the palace to seek the true purpose of life, Siddhartha first tried the path of severe asceticism, only to abandon it after six years as a futile exercise. He then sat down in yogic meditation beneath a bodhi tree until he achieved enlightenment. He was known henceforth as the Buddha, or “Enlightened One.”

His is the Middle Path, rejecting both luxury and asceticism. Buddhism proposes a life of good thoughts, good intentions, and straight living, all with the ultimate aim of achieving nirvana, release from earthly existence. For most beings, nirvana lies in the distant future, because Buddhism, like other faiths of India, believes in a cycle of rebirth. Humans are born many times on earth, each time with the opportunity to perfect themselves further. And it is their own karma—the sum total of deeds, good and bad—that determines the circumstances of a future birth. The Buddha spent the remaining forty years of his life preaching his faith and making vast numbers of converts. When he died, his body was cremated, as was customary in India.

The cremated relics of the Buddha were divided into several portions and placed in relic caskets that were interred within large hemispherical mounds known as stupas. Such stupas constitute the central monument of Buddhist monastic complexes. They attract pilgrims from far and wide who come to experience the unseen presence of the Buddha. Stupas are enclosed by a railing that provides a path for ritual circumambulation. The sacred area is entered through gateways at the four cardinal points.

In the first century B.C., India’s artists, who had worked in the perishable media of brick, wood, thatch, and bamboo, adopted stone on a very wide scale. Stone railings and gateways, covered with relief sculptures, were added to stupas. Favorite themes were events from the historic life of the Buddha, as well as from his previous lives, which were believed to number 550. The latter tales are called jatakas and often include popular legends adapted to Buddhist teachings.

In the earliest Buddhist art of India, the Buddha was not represented in human form. His presence was indicated instead by a sign, such as a pair of footprints, an empty seat, or an empty space beneath a parasol.

In the first century A.D., the human image of one Buddha came to dominate the artistic scene, and one of the first sites at which this occurred was along India’s northwestern frontier. In the area known as Gandhara, artistic elements from the Hellenistic world combined with the symbolism needed to express Indian Buddhism to create a unique style. Youthful Buddhas with hair arranged in wavy curls resemble Roman statues of Apollo; the monastic robe covering both shoulders and arranged in heavy classical folds is reminiscent of a Roman toga. There are also many representations of Siddhartha as a princely bejeweled figure prior to his renunciation of palace life. Buddhism evolved the concept of a Buddha of the Future, Maitreya, depicted in art both as a Buddha clad in a monastic robe and as a princely bodhisattva before enlightenment. Gandharan artists made use of both stone and stucco to produce such images, which were placed in nichelike shrines around the stupa of a monastery. Contemporaneously, the Kushan-period artists in Mathura, India, produced a different image of the Buddha. His body was expanded by sacred breath (prana), and his clinging monastic robe was draped to leave the right shoulder bare.

A third influential Buddha type evolved in Andhra Pradesh, in southern India, where images of substantial proportions, with serious, unsmiling faces, were clad in robes that created a heavy swag at the hem and revealed the left shoulder. These southern sites provided artistic inspiration for the Buddhist land of Sri Lanka, off the southern tip of India, and Sri Lankan monks regularly visited the area. A number of statues in this style have been found as well throughout Southeast Asia.

The succeeding Gupta period, from the fourth to the sixth century A.D., in northern India, sometimes referred to as a Golden Age, witnessed the creation of an “ideal image” of the Buddha. This was achieved by combining selected traits from the Gandharan region with the sensuous form created by Mathura artists. Gupta Buddhas have their hair arranged in tiny individual curls, and the robes have a network of strings to suggest drapery folds (as at Mathura) or are transparent sheaths (as at Sarnath). With their downward glance and spiritual aura, Gupta Buddhas became the model for future generations of artists, whether in post-Gupta and Pala India or in Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia. Gupta metal images of the Buddha were also taken by pilgrims along the Silk Road to China.

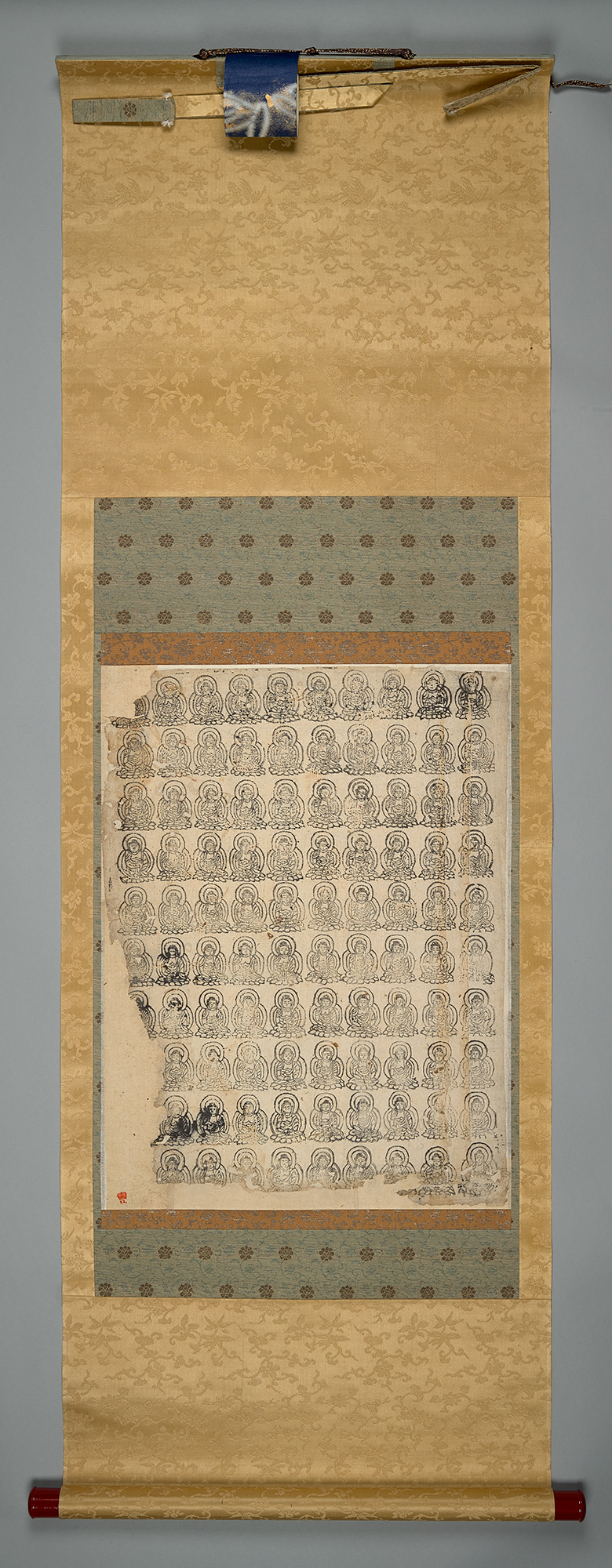

Over the following centuries there emerged a new form of Buddhism that involved an expanding pantheon and more elaborate rituals. This later Buddhism introduced the concept of heavenly bodhisattvas as well as goddesses, of whom the most popular was Tara. In Nepal and Tibet, where exquisite metal images and paintings were produced, new divinities were created and portrayed in both sculpture and painted scrolls. Ferocious deities were introduced in the role of protectors of Buddhism and its believers. Images of a more esoteric nature, depicting god and goddess in embrace, were produced to demonstrate the metaphysical concept that salvation resulted from the union of wisdom (female) and compassion (male). Buddhism had traveled a long way from its simple beginnings.

Explore more Buddhist sculpture from the Metropolitan Museum of Art here: Buddhism and Buddhist Art | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (metmuseum.org)

Copyright: Dehejia, Vidya. “Buddhism and Buddhist Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/budd/hd_budd.htm (February 2007)

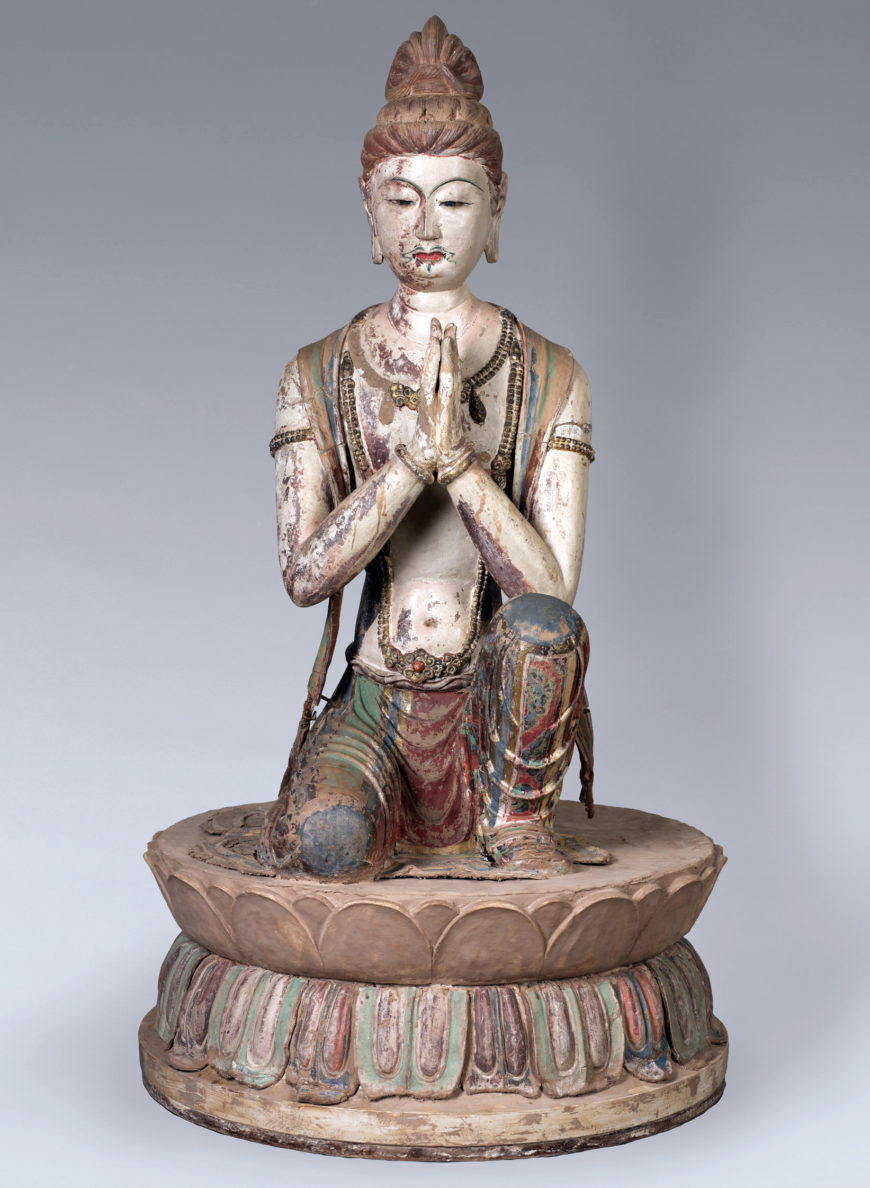

Bodhisattvas

What is a bodhisattva?

In Sanskrit, bodhisattva roughly means: “being who intends to become a buddha.”

In the Theravada tradition of Buddhism, the Buddha referred to himself as bodhisattva during all of his incarnations and lifetimes before he achieved enlightenment. It was only after he achieved buddhahood that it became proper to refer to him as the Buddha.

In the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism, a bodhisattva is any being who intends to achieve enlightenment and buddhahood.

[…] Western literature often describes the bodhisattva as someone who postpones his enlightenment in order to save all beings from suffering […] by choosing this longer course, he perfects himself over many lifetimes in order to achieve the superior enlightenment of a buddha at a point in the far-distant future […]The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, edited by Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez, p. 134.

In Buddhist artistic traditions, there are many archetypal bodhisattva figures who appear repeatedly. In this essay we will look at five of them.

These specific bodhisattva figures may be depicted as either male or female, depending on the geographic context and the iconographic traditions of that culture.

Paintings of two archetypal bodhisattva figures are found in the Ajanta Caves in Maharashta, India. These figures flank a statue of the Buddha. The one on the left is named Padmapani, and the one to the right is named Vajrapani.

Another artwork from Indonesia features the same theme. The Buddha sits in the center flanked by the two bodhisattvas: Padmapani on the left and Vajrapani on the right.

Avalokitesvara

Padmapani is another name in Sanskrit for Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who represents the compassion of all of the Buddhas.

In China, the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara goes by the name Guanyin. Chinese art often depicts Avalokitesvara as female.

Vajrapani

The Bodhisattva Vajrapani represents the power of all the Buddhas, and he protects the Buddha. Below he is depicted wielding a lightning-bolt scepter in his left hand.

Thanks to cultural contact between the Kushan Empire and what is today northern India, the Bodhisattva Vajrapani has a strong iconographical relationship with the Greek mythological figure of Hercules as found in Gandharan art.

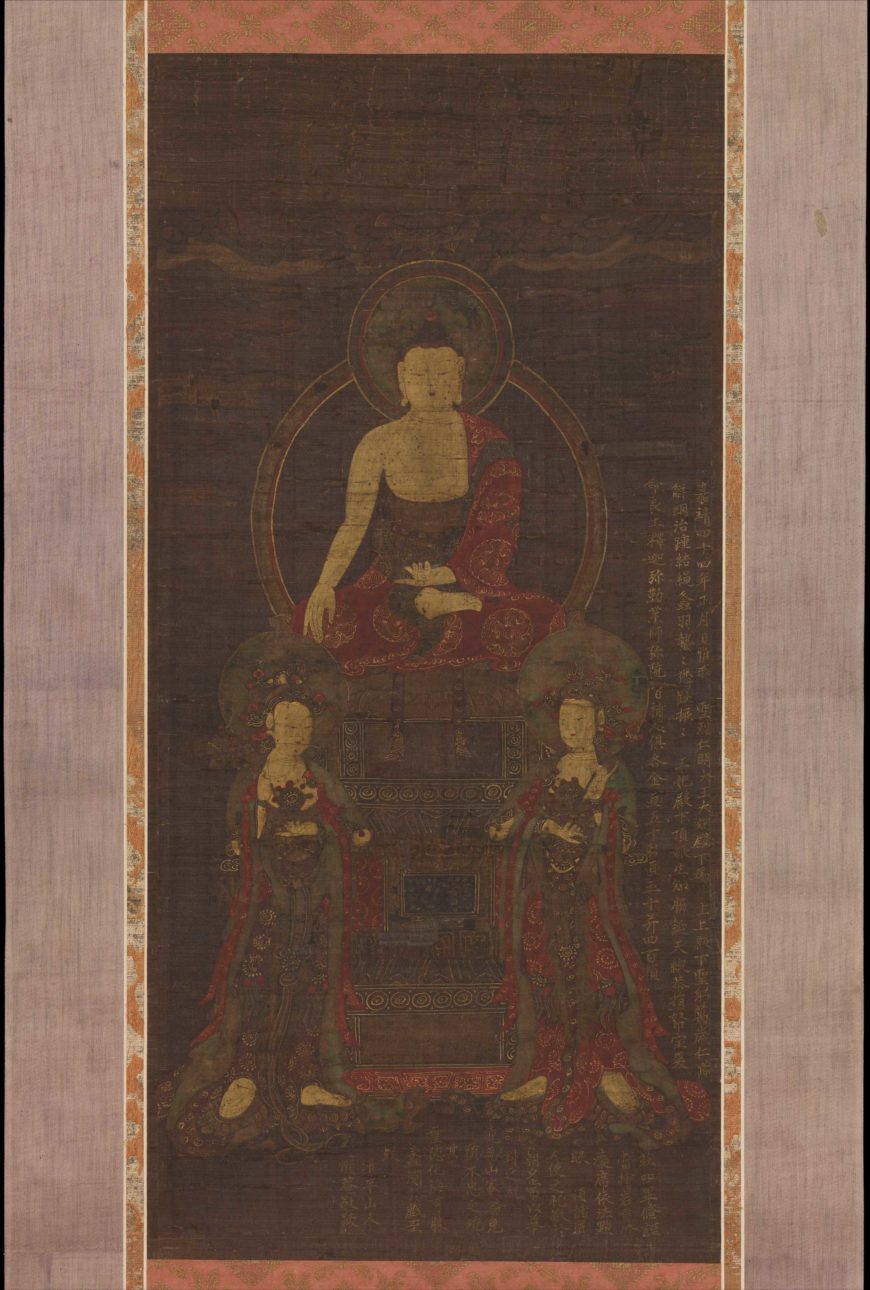

Manjusri and Samantabhadra

Besides the bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani, another pair of popular archetypal bodhisattvas are Manjusri and Samantabhadra.

In a Joseon dynasty painting, the Buddha sits in the center with Bodhisattva Manjusri and Bodhisattva Samantabhadra at his side. This is called the Shakyamuni Trinity or Triad.

Manjusri

Manjusri is often depicted with a lion, as seen in a peaceful painting by Japanese artist Shūsei.

The Bodhisattva Manjusri represents the wisdom of all the Buddhas. Sometimes he is depicted holding a sword or a scepter. In China, Manjusri is known as Wenshu, and in Japan he is known as Monju.

Samantabhadra