47 CENTRAL ASIA

In this chapter

- Geography and History

- Religion and Philosophy

- Literature

- Architecture

- Performing Arts

- Visual Arts

GEOGRAPHY and HISTORY

British Colonialism in India

The Indian Mutiny of 1857, also known as the Sepoy Rebellion, was an attempt to overthrow British rule. The British East India Company’s preference for indirect rule had changed as its successes in India convinced British leaders they were capable of governing it directly. As Indian elites saw their power slipping away, they became more interested in opposing British rule. Waves of European missionaries who sought to convert Indians to Christianity had also offended many who wanted to preserve their own traditions.

The activities of Christian missionaries were only one cause of Indian resentment. Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general of India from 1848 to 1856, had devised a means of gaining direct control for the British over formerly independent Indian states. It was Hindu custom for a ruler who did not have a natural heir to adopt one and to pass his kingdom to him upon his death. Dalhousie, however, introduced the doctrine of the lapse, which gave Britain the right to approve any such adoptions and to annex states without heirs. Under this policy, adoptions were rejected and states annexed beginning in 1848. Even though the practice affected primarily states with Hindu rulers, British usurpation alarmed all members of India’s aristocracy.

Britain’s confidence in the superiority of its own culture also led it to attempt changes in customary Hindu practices in ways that angered many Indians. The British attempted to end the Hindu practice of sati (suttee), in which Hindu widows were expected to burn themselves alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres, and passed a law allowing these widows to remarry. The British also introduced Western schooling with English as the language of instruction, not Persian, the language favored by the Mughals and the language of literature and scholarship in many Islamic empires. The young men who attended these schools were preferred by the British for positions in business and government. Because British schools were more prevalent in Hindu-majority areas, Hindus threatened to supplant Muslims in positions of authority that Muslims had held for centuries.

Long-simmering anger against the British turned into violence in response to the introduction of the Enfield Rifle, which used lubricated cartridges that soldiers had to bite open before loading. The lubricant had been beef or pork fat, but pork is taboo for Muslims and Hindus believe cows are sacred. The British attempted to correct the problem by using another lubricant, but Indian troops remained suspicious and some began to believe the British were intentionally using lubricants made of offensive materials to emasculate the sepoys. In March 1857, a sepoy named Mangal Pandey, a devout Hindu from the high-ranking Brahmin caste, attacked two British officers. The British executed him, and India erupted into a mass revolt.

The rebelling Indians outnumbered the British during the mutiny, but the British were unified while the Indians were unable to work together across religious, ethnic, and geographic divisions. After a series of fierce battles and war crimes by both sides, the British declared victory on July 8, 1859. They celebrated with mass executions of rebel leaders, a move some British officers criticized. The Indian Mutiny convinced the British government that the owners of the British East India Company were unable to effectively govern India. The government thus abolished the company, took control of British India in 1858, and directly ruled the territory until it became independent in 1947. The period from 1858 to 1947 is therefore known as the British Raj (raj means “rule” in Sanskrit), or the British Paramountcy, which meant rule of India by the British government through the Viceroy of India.

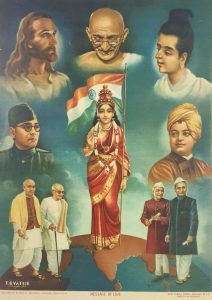

An Independent India

The significant role their troops in the British Army had played in World War I offered Indians some hope that Britain might now extend them more rights than before. Indians were also anxious to have the British government’s restrictive wartime measures lifted. However, it soon became clear that Britain had no plans for change. So, as in many other countries, in India a growing nationalist movement now advocated independence from colonial rule. The clash between Indian Nationalists and British rulers began almost immediately after the end of World War I.

In early April 1919, Indians began to gather in a walled square in Amritsar, a city in Punjab that was sacred to the Sikh population. They were protesting the passage of the Rowlatt Act, which allowed Indians suspected of engaging in revolutionary activities to be detained for two years without trial. At times the protests turned violent. Then, on April 13, the British Indian Army opened fire on the protestors, who had little chance of escape from the closed-in space. Hundreds were killed and more than a thousand wounded. The British commander of the unit ultimately resigned after an investigation. The massacre prompted the British government to make some legislative changes in India regarding who was eligible to vote and how many Indian representatives could sit in the national assembly. However, this small concession did not quell the continued criticism from Indian nationalists, who urged independence and self-rule. The Indian National Congress argued that India should be ruled by Indians. Its members proposed continued nonviolent disobedience and boycotts against British goods, along with a refusal to pay certain taxes.

In this chaotic and emotional situation, a lawyer named Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi began to take center stage. Gandhi adopted and advocated the practice of civil disobedience and nonviolence, wore traditional modes of dress, and renounced material possessions. In the 1920s, the movement for self-rule became a grassroots operation preaching civil disobedience to people throughout India. Gandhi became head of the Indian National Congress in 1921, and it soon became the party of the masses.

Many British rules flew in the face of Indian traditions, such as those regarding the collection of salt, a common element of the Indian diet. Under the colonial system, Indians could not gather or sell salt; instead, they had to purchase it from the British and pay a heavy tax. On March 12, 1930, Gandhi began a protest known as the Salt March, in which he led his supporters on a two-hundred-mile, twenty-four-day march to the Arabian Sea to collect salt from the seawater. Despite British efforts to obscure the salt deposits at the beaches, Gandhi and his followers did collect salt, in violation of British law (Figure 12.17Figure B12_04_GandhiSalt). He and approximately sixty thousand others were arrested for these acts of civil disobedience. In numerous locations over the next several weeks, other nationalists similarly began collecting salt at coastlines in defiance of the law. Gandhi was not released from jail until the following year and agreed to suspend the mass act of civil disobedience.

While the British were not inclined to embrace India’s independence movement, within a few years they did begin to relent on the question of self-rule. While retaining control of the military and foreign policy functions, they turned other government operations over to Indians via the Government of India Act in 1935. This was an important step toward more autonomy for India. Muslim representation in India remained an issue, however. For example, the Indian National Congress was dominated by the Hindu majority, but rather than recognizing that body as representing all those living in India, the British recognized the separate Muslim League as the representatives of the Muslim population. The Indian National Congress had achieved a measure of its agenda in favor of self-rule, but India was still clearly under British control.

India sought to plot its own path and remain free of the entangling alliances of the Cold War, and it was also one of the initiators of the Non-Aligned Movement. In 1947, the United Kingdom granted India its independence. Anti-British protests had rocked India throughout 1946, and, exhausted from fighting World War II, Britain could no longer afford to maintain control over its colony. In addition, although the United Kingdom had sufficient troops there, the majority were Indian, and it was uncertain where their loyalties lay. Indeed, in 1946 Indians in the British Navy had mutinied throughout the country. Finally, the United Kingdom’s greatest ally and creditor, the United States, pressured the nation to grant India its independence, as the United States had given independence to the Philippines following the war.

The announcement that the British would be withdrawing sparked waves of religious violence throughout the nation. Much of it was caused by a dispute over what an independent India would consist of. Hindus in the Indian National Congress called for the maintenance of a single, unified India. Muslims, however, feared that the Hindu majority would dominate the government to their detriment, and many were reluctant to agree to such a situation. A compromise was reached, and at midnight on August 15, 1947, when India achieved its independence, the region of Pakistan, home to a Muslim majority, became an independent nation as well.

Kordas, A., Lynch, R. J., Nelson, B., & Tatlock, J. (2022). In World History Volume 2, from 1400. OpenStax.

RELIGION and PHILOSOPHY

Celebrating the Destruction of Objects in South Asia

A photograph by artist Ketaki Sheth depicts a little girl, wearing a lacy floral dress and standing upon the shoulders of a man, perhaps her father, to get a better view of the surrounding crowd that carries a large sculptural image of the Hindu god Ganesha. Sheth captures a moment of stillness during an otherwise boisterous and energetic occasion: the artist brings us above the crowd and into the clouds that backlight the richly adorned body of the elephant-headed deity—remover of obstacles and son of Shiva and Parvati—on his way toward a body of water for ritual immersion during the annual festival of Ganesha Chaturthi.

Impermanence and belief

The practice of ritually submerging, and thereby destroying, sculptural images of Ganesha during Ganesha Chaturthi represents one of several religious and cultural acts in South Asia which complicate ideas about the value and permanence of material objects. Makers involved in these practices produce objects and artistic depictions with the knowledge that the products of their creative labor are temporary and will be intentionally destroyed or deteriorate over time. In some cases these practices of ritual destruction resonate with ideas about the cyclical nature of time as described in concepts like samsara. In other cases the destruction of an object is symbolic of the removal of evil and the restoration of good in the universe. In still other cases, we find beautifully wrought material objects whose impermanence is embedded in their form and function, much like disposable paper plates.

These examples challenge us to push against the preciousness of objects—an approach that we encounter so often in the study of art—and to rethink the way we value the permanence / impermanence of material things. This call to rethink our valuation of objects is also critical to the decolonizing of the discipline of art history; privileging objects of durable and precious materials over ephemeral works of art (such as things made from unfired clay, paper, or cotton fiber) is in many ways a legacy of British colonial rule on the subcontinent that sought to promote a Eurocentric view and valuation of objects and artistic practices.[1]

For the Ganesha images created in celebration of Ganesha Chaturthi, their destruction is a joyous celebration. Occurring in August or September of each year according to the Hindu lunar calendar, the ritual immersion of Ganesha marks the deity’s birth and symbolic return to the earth. [2] According to legend, Ganesha was created from clay by the goddess Parvati and was given an elephant’s head after his father, the god Shiva, inadvertently beheaded him. Ganesha Chaturthi celebrates the moment when the deity received his elephant head, and his ritual immersion in water each year following ten days of rites is a significant event that bestows blessings on devotees.

Immersion as purification

It is not surprising that worshippers laboriously carry sacred sculptural images or murtis of Ganesha to local bodies of water for ritual immersion. Water is a symbolic purifier in South Asia and used in numerous religious and cultural practices connected with worshipping Hindu gods and goddesses as well as honoring holy figures, saints, and sacred architecture in Buddhist, Christian, Jain, Muslim, and Sikh beliefs. For the Hindu devotees participating in ritual immersion festivals like Ganesha Chaturthi, the water itself is sacred and ultimately connected to the holiest river in India, the Ganga.[3]

Historically, artists made disposable or perishable murtis of the god from unfired clay or low-fired terracotta decorated with natural pigments. [4] These images would slowly dissolve in water and eventually be reincorporated into the ecosystem. However, over the last several decades increasingly larger Ganesha images made from synthetic paints, gypsum plaster (plaster of Paris), and plastic ornaments have become popular, and the heavy metals and toxins associated with these raw materials have leached into India’s waterways, creating dangerous amounts of pollution. [5] Recently, the Government of India’s Central Pollution Control Board established rules requiring that devotees use Ganesha murtis made from biodegradable materials (like terracotta) and have encouraged that ritual immersion practices occur in specially-designated water tanks.

In addition to annual events like Ganesha Chaturthi, the making of temporary, perishable objects and artistic depictions appear on a daily basis in many parts of India through the creation of decorative floor paintings known by various names including alpana, kollam, and rangoli. [6] Typically made by female members of a household or community using rice flour, chalk, powdered pigments, or flowers, the symmetrical forms of these temporary paintings symbolize divine power. They are intended to sanctify a space, and have ancient origins in goddess worship. [7] For special festivals some women create particularly elaborate floor paintings that last for several months or even up to a year. There are many, however, who treat this practice as a daily ritual with the intention that the painting will be swept clean and remade each morning—the epitome of intangible cultural heritage. [8]

Destroying the demon king

A particularly dramatic example of the ritual destruction of objects occurs with sculptural effigies of the demon king Ravana and his demon armies which are burned and physically torn apart during multi-day performances of the Ramacharitamanas, the Hindi version of the story of Rama which is especially popular throughout North India and famously performed in the city of Ramnagar. [9] This performance, known locally as Ramlila, narrates the story of Rama, an earthly form or avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, who is the beloved king of the city of Ayodhya and husband to Sita, an avatar of the goddess Lakshmi. The Ramacharitamanas, similar to the Sanskrit Ramayana, describes the adventures of Rama, his brother Lakshmana, and Sita during their fourteen-year exile from Ayodhya. The story culminates in a series of battles between Rama and the powerful demon king, Ravana, who has abducted Sita and held her captive at his palace in Lanka.

In the final days of the Ramlila performance, sculptural depictions of Ravana and other demons made from bamboo and paper are set ablaze to symbolize their mythological destruction. The most dramatic moment in the Ramlila performance occurs on Dussehra, an important Hindu festival celebrated throughout India, when participants destroy sculptural depictions of Ravana, sometimes 75-feet tall and filled with firecrackers, to mark Rama’s victory over the demon king and the ultimate victory of good over evil.

In other parts of India, Dusshera is celebrated as a way to mark the goddess Durga’s victory over the buffalo demon Mahishasura, understood by devotees as a mythological act that restores dharma to the universe. Worshippers celebrate Dusshera by creating elaborate temporary altars or pandals for Durga, many of which are then submerged in water on Dusshera, marking the culmination of nine nights of celebration known as Navratri. The pandals made for the worship or puja of Durga are most famously created in Bengal where families, neighborhoods, community organizations, and businesses commission elaborate pandals that incorporate depictions of iconic architecture and motifs from popular culture. [10]

A photograph by artist Raghu Rai depicts the ritual immersion of Durga during a Dusshera celebration in Kolkata. In Rai’s image we see a larger-than-life murti of Durga being carried with bamboo poles to the Ganga by several human figures—a scene that parallels depictions of Ganesha Chaturthi. These human devotees work together to hoist the goddess into the river. We see Durga’s many arms clearly holding the weapons she uses to vanquish Mahishasura and her lion mount or vahana with its mouth agape seated nearby. A nineteenth-century painting of a similar moment suggests earlier practices of this form of ritual immersion. While the focus in the painting is on the elaborately adorned murti of Durga and the human devotees who carry her pandal in procession, in the foreground of the scene appears loose brushstrokes that hint at water, perhaps a subtle indication of the immersion to come.

Flowers and cups

The practice of ritually submerging or destroying images is not limited to depictions of gods, goddesses, or demons, but even applies to the floral garlands that adorn many sacred images. The practice of alankara or adorning a murti includes dressing the deity in strands of marigolds, roses, and jasmine flowers. Floral offerings are also used in worship at other religious sites in India including Sufi shrines, Sikh temples, and Christian churches. These flowers are most often tossed into water after their use in religious rites. Once blessed by the divine these floral offerings need to be disposed of in the holiest way possible, either scattered in a sacred river like the Ganga or immersed in a local body of water.

LITERATURE

Benkim Chandra Chatterjee

Benkim Chandra Chatterjee was an Indian author born in Bengal. His education was largely British, and he was one of the first to graduate from the University of Calcutta. His writing is groundbreaking for his work using European style prose in the Bengali language. He incorporated nationalist themes into his writing. He wrote Anandamath, a novel widely considered one of the most important works of literature in Idia, which contacted “Bande Mataram” (“Hail to Tee, Mother”). “Bande Mataram” was so inspiring to the people that it was adopted by the nationalist movement. In his efforts, he combined Hindu heroes and patriotism that, in turn, inspired national pride in some of his countrymen, but did alienate some Muslim Indians. His novel The Poison Tree (Bishabriksha) first appeared serialized in 1873. His novel explores the moral dilemma of a love triangle between a man, his wife, and a young widow, which also explores the areas of widow remarriage.

Consider while reading:

- How does Chatterjee’s protagonist incorporate Hindu ideas and beliefs? Why is that significant?

- What social norms is Chatterjee questioning his work? Why?

- What alternative does Chatterjee offer for widows? Why is that significant?

Read the full version of The Poison Tree here: “The Poison Tree” in “Compact Anthology of World Literature, Part Five: The Long Nineteenth Century” | OpenALG (manifoldapp.org)

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranaht Tagore was outspoken on the differences between Modernism in India and in Europe. During lectures that he gave in Japan from 1916-1917, Tagore argued that India’s lack of modernization did not mean that they were not participants in Modernism, which he defined as a “freedom of mind” from one’s own traditions, rather than participating in the cultural trends of Europe. Tagore was born into an influential family in the Bengal region of India, during the Bengal Renaissance (a particularly creative time period for art and literature, along with social reforms and scientific advances). Tagore’s father and several siblings were famous for their contributions in many areas, including literature, music, and philosophy; one of his sisters, Swarnakumari Devi, was a novelist, editor, and social reformer in a time period when women rarely attended school. Tagore surpassed them all. He wrote poetry, short stories, plays, essays, and songs. Both India and Bangladesh chose songs for his for their national anthems. He originally wrote his literary works in Bengali, later translating them to English himself, or personally overseeing their translation. In 1913, he became the first non-Western writers to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. Tagore’s keen awareness of cultural (and linguistic) differences in society informs the short story Cabuliwallah (1892). The narrator, a progressive-minded Hindu in Calcutta, observes the friendship between his (adopted) daughter Mini and a Muslim fruit-seller from Kabul, who misses his own daughter. The story delicately balances a range of issues, including socio-economic status, religion, prejudice, the tension between traditional and modern views of life, and even the five-year-old Mini’s lack of experience with language. In the end, however, these elements come together to support the main issue: the definition of what a “real” family is.

The Cabuliwallah

My five years’ old daughter Mini cannot live without chattering. I really believe that in all her life she has not wasted a minute in silence. Her mother is often vexed at this, and would stop her prattle, but I would not. To see Mini quiet is unnatural, and I cannot bear it long. And so my own talk with her is always lively.

One morning, for instance, when I was in the midst of the seventeenth chapter of my new novel, my little Mini stole into the room, and putting her hand into mine, said: “Father! Ramdayal the door-keeper calls a crow a krow! He doesn’t know anything, does he?”

Before I could explain to her the differences of language in this world, she was embarked on the full tide of another subject. “What do you think, Father? Bhola says there is an elephant in the clouds, blowing water out of his trunk, and that is why it rains!”

And then, darting off anew, while I sat still making ready some reply to this last saying: “Father! what relation is Mother to you?”

With a grave face I contrived to say: “Go and play with Bhola, Mini! I am busy!”

The window of my room overlooks the road. The child had seated herself at my feet near my table, and was playing softly, drumming on her knees. I was hard at work on my seventeenth chapter, where Pratap Singh, the hero, had just caught Kanchanlata, the heroine, in his arms, and was about to escape with her by the third-story window of the castle, when all of a sudden Mini left her play, and ran to the window, crying: “A Cabuliwallah! a Cabuliwallah!” Sure enough in the street below was a Cabuliwallah, passing slowly along. He wore the loose, soiled clothing of his people, with a tall turban; there was a bag on his back, and he carried boxes of grapes in his hand.

I cannot tell what were my daughter’s feelings at the sight of this man, but she began to call him loudly. “Ah!” I thought, “he will come in, and my seventeenth chapter will never be finished!” At which exact moment the Cabuliwallah turned, and looked up at the child. When she saw this, overcome by terror, she fled to her mother’s protection and disappeared. She had a blind belief that inside the bag, which the big man carried, there were perhaps two or three other children like herself. The pedlar meanwhile entered my doorway and greeted me with a smiling face.

So precarious was the position of my hero and my heroine, that my first impulse was to stop and buy something, since the man had been called. I made some small purchases, and a conversation began about Abdurrahman, the Russians, the English, and the Frontier Policy.

As he was about to leave, he asked: “And where is the little girl, sir?”

And I, thinking that Mini must get rid of her false fear, had her brought out.

She stood by my chair, and looked at the Cabuliwallah and his bag. He offered her nuts and raisins, but she would not be tempted, and only clung the closer to me, with all her doubts increased.

This was their first meeting.

One morning, however, not many days later, as I was leaving the house, I was startled to find Mini, seated on a bench near the door, laughing and talking, with the great Cabuliwallah at her feet. In all her life, it appeared, my small daughter had never found so patient a listener, save her father. And already the corner of her little sari was stuffed with almonds and raisins, the gift of her visitor. “Why did you give her those?” I said, and taking out an eight-anna bit, I handed it to him. The man accepted the money without demur, and slipped it into his pocket.

Alas, on my return an hour later, I found the unfortunate coin had made twice its own worth of trouble! For the Cabuliwallah had given it to Mini; and her mother, catching sight of the bright round object, had pounced on the child with: “Where did you get that eight-anna bit?”

“The Cabuliwallah gave it me,” said Mini cheerfully.

“The Cabuliwallah gave it you!” cried her mother much shocked. “O Mini! how could you take it from him?”

I, entering at the moment, saved her from impending disaster, and proceeded to make my own inquiries.

It was not the first or second time, I found, that the two had met. The Cabuliwallah had overcome the child’s first terror by a judicious bribery of nuts and almonds, and the two were now great friends.

They had many quaint jokes, which afforded them much amusement. Seated in front of him, looking down on his gigantic frame in all her tiny dignity, Mini would ripple her face with laughter and begin: “O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah! what have you got in your bag?”

And he would reply, in the nasal accents of the mountaineer: “An elephant!” Not much cause for merriment, perhaps; but how they both enjoyed the fun! And for me, this child’s talk with a grown-up man had always in it something strangely fascinating.

Then the Cabuliwallah, not to be behindhand, would take his turn: “Well, little one, and when are you going to the father-in-law’s house?”

Now most small Bengali maidens have heard long ago about the father-in-law’s house; but we, being a little new-fangled, had kept these things from our child, and Mini at this question must have been a trifle bewildered. But she would not show it, and with ready tact replied: “Are you going there?”

Amongst men of the Cabuliwallah’s class, however, it is well known that the words father-in-law’s house have a double meaning. It is a euphemism for jail, the place where we are well cared for, at no expense to ourselves. In this sense would the sturdy pedlar take my daughter’s question. “Ah,” he would say, shaking his fist at an invisible policeman, “I will thrash my father-in-law!” Hearing this, and picturing the poor discomfited relative, Mini would go off into peals of laughter, in which her formidable friend would join.

These were autumn mornings, the very time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it, and at the sight of a foreigner in the streets, I would fall to weaving a network of dreams,—the mountains, the glens, and the forests of his distant home, with his cottage in its setting, and the free and independent life of far-away wilds. Perhaps the scenes of travel conjure themselves up before me and pass and repass in my imagination all the more vividly, because I lead such a vegetable existence that a call to travel would fall upon me like a thunder-bolt. In the presence of this Cabuliwallah I was immediately transported to the foot of arid mountain peaks, with narrow little defiles twisting in and out amongst their towering heights. I could see the string of camels bearing the merchandise, and the company of turbanned merchants carrying some their queer old firearms, and some their spears, journeying downward towards the plains. I could see—. But at some such point Mini’s mother would intervene, imploring me to “beware of that man.”

Mini’s mother is unfortunately a very timid lady. Whenever she hears a noise in the street, or sees people coming towards the house, she always jumps to the conclusion that they are either thieves, or drunkards, or snakes, or tigers, or malaria, or cockroaches, or caterpillars. Even after all these years of experience, she is not able to overcome her terror. So she was full of doubts about the Cabuliwallah, and used to beg me to keep a watchful eye on him.

I tried to laugh her fear gently away, but then she would turn round on me seriously, and ask me solemn questions:—

Were children never kidnapped?

Was it, then, not true that there was slavery in Cabul?

Was it so very absurd that this big man should be able to carry off a tiny child?

I urged that, though not impossible, it was highly improbable. But this was not enough, and her dread persisted. As it was indefinite, however, it did not seem right to forbid the man the house, and the intimacy went on unchecked.

Once a year in the middle of January Rahmun, the Cabuliwallah, was in the habit of returning to his country, and as the time approached he would be very busy, going from house to house collecting his debts. This year, however, he could always find time to come and see Mini. It would have seemed to an outsider that there was some conspiracy between the two, for when he could not come in the morning, he would appear in the evening.

Even to me it was a little startling now and then, in the corner of a dark room, suddenly to surprise this tall, loose-garmented, much bebagged man; but when Mini would run in smiling, with her “O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!” and the two friends, so far apart in age, would subside into their old laughter and their old jokes, I felt reassured.

One morning, a few days before he had made up his mind to go, I was correcting my proof sheets in my study. It was chilly weather. Through the window the rays of the sun touched my feet, and the slight warmth was very welcome. It was almost eight o’clock, and the early pedestrians were returning home with their heads covered. All at once I heard an uproar in the street, and, looking out, saw Rahmun being led away bound between two policemen, and behind them a crowd of curious boys. There were blood-stains on the clothes of the Cabuliwallah, and one of the policemen carried a knife. Hurrying out, I stopped them, and inquired what it all meant. Partly from one, partly from another, I gathered that a certain neighbour had owed the pedlar something for a Rampuri shawl, but had falsely denied having bought it, and that in the course of the quarrel Rahmun had struck him. Now, in the heat of his excitement, the prisoner began calling his enemy all sorts of names, when suddenly in a verandah of my house appeared my little Mini, with her usual exclamation: “O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!” Rahmun’s face lighted up as he turned to her. He had no bag under his arm to-day, so she could not discuss the elephant with him. She at once therefore proceeded to the next question: “Are you going to the father-in-law’s house?” Rahmun laughed and said: “Just where I am going, little one!” Then, seeing that the reply did not amuse the child, he held up his fettered hands. “Ah!” he said, “I would have thrashed that old father-in-law, but my hands are bound!”

On a charge of murderous assault, Rahmun was sentenced to some years’ imprisonment.

Time passed away and he was not remembered. The accustomed work in the accustomed place was ours, and the thought of the once free mountaineer spending his years in prison seldom or never occurred to us. Even my light-hearted Mini, I am ashamed to say, forgot her old friend. New companions filled her life. As she grew older, she spent more of her time with girls. So much time indeed did she spend with them that she came no more, as she used to do, to her father’s room. I was scarcely on speaking terms with her.

Years had passed away. It was once more autumn and we had made arrangements for our Mini’s marriage. It was to take place during the Puja Holidays. With Durga returning to Kailas, the light of our home also was to depart to her husband’s house, and leave her father’s in the shadow.

The morning was bright. After the rains, there was a sense of ablution in the air, and the sun-rays looked like pure gold. So bright were they, that they gave a beautiful radiance even to the sordid brick walls of our Calcutta lanes. Since early dawn that day the wedding-pipes had been sounding, and at each beat my own heart throbbed. The wail of the tune, Bhairavi, seemed to intensify my pain at the approaching separation. My Mini was to be married that night.

From early morning noise and bustle had pervaded the house. In the courtyard the canopy had to be slung on its bamboo poles; the chandeliers with their tinkling sound must be hung in each room and verandah. There was no end of hurry and excitement. I was sitting in my study, looking through the accounts, when some one entered, saluting respectfully, and stood before me. It was Rahmun the Cabuliwallah. At first I did not recognise him. He had no bag, nor the long hair, nor the same vigour that he used to have. But he smiled, and I knew him again.

“When did you come, Rahmun?” I asked him.

“Last evening,” he said, “I was released from jail.”

The words struck harsh upon my ears. I had never before talked with one who had wounded his fellow, and my heart shrank within itself when I realised this; for I felt that the day would have been better-omened had he not turned up.

“There are ceremonies going on,” I said, “and I am busy. Could you perhaps come another day?”

At once he turned to go; but as he reached the door he hesitated, and said: “May I not see the little one, sir, for a moment?” It was his belief that Mini was still the same. He had pictured her running to him as she used, calling “O Cabuliwallah! Cabuliwallah!” He had imagined too that they would laugh and talk together, just as of old. In fact, in memory of former days he had brought, carefully wrapped up in paper, a few almonds and raisins and grapes, obtained somehow from a countryman; for his own little fund was dispersed.

I said again: “There is a ceremony in the house, and you will not be able to see any one to-day.”

The man’s face fell. He looked wistfully at me for a moment, then said “Good morning,” and went out.

I felt a little sorry, and would have called him back, but I found he was returning of his own accord. He came close up to me holding out his offerings with the words: “I brought these few things, sir, for the little one. Will you give them to her?”

I took them and was going to pay him, but he caught my hand and said: “You are very kind, sir! Keep me in your recollection. Do not offer me money!—You have a little girl: I too have one like her in my own home. I think of her, and bring fruits to your child—not to make a profit for myself.”

Saying this, he put his hand inside his big loose robe, and brought out a small and dirty piece of paper. With great care he unfolded this, and smoothed it out with both hands on my table. It bore the impression of a little hand. Not a photograph. Not a drawing. The impression of an ink-smeared hand laid flat on the paper. This touch of his own little daughter had been always on his heart, as he had come year after year to Calcutta to sell his wares in the streets.

Tears came to my eyes. I forgot that he was a poor Cabuli fruit-seller, while I was—. But no, what was I more than he? He also was a father.

That impression of the hand of his little Pārbati in her distant mountain home reminded me of my own little Mini.

I sent for Mini immediately from the inner apartment. Many difficulties were raised, but I would not listen. Clad in the red silk of her wedding-day, with the sandal paste on her forehead, and adorned as a young bride, Mini came, and stood bashfully before me.

The Cabuliwallah looked a little staggered at the apparition. He could not revive their old friendship. At last he smiled and said: “Little one, are you going to your father-in-law’s house?”

But Mini now understood the meaning of the word “father-in-law,” and she could not reply to him as of old. She flushed up at the question, and stood before him with her bride-like face turned down.

I remembered the day when the Cabuliwallah and my Mini had first met, and I felt sad. When she had gone, Rahmun heaved a deep sigh, and sat down on the floor. The idea had suddenly come to him that his daughter too must have grown in this long time, and that he would have to make friends with her anew. Assuredly he would not find her as he used to know her. And besides, what might not have happened to her in these eight years?

The marriage-pipes sounded, and the mild autumn sun streamed round us. But Rahmun sat in the little Calcutta lane, and saw before him the barren mountains of Afghanistan.

I took out a bank-note and gave it to him, saying: “Go back to your own daughter, Rahmun, in your own country, and may the happiness of your meeting bring good fortune to my child!”

Having made this present, I had to curtail some of the festivities. I could not have the electric lights I had intended, nor the military band, and the ladies of the house were despondent at it. But to me the wedding-feast was all the brighter for the thought that in a distant land a long-lost father met again with his only child.

Original found at The Cabuliwallah (americanliterature.com), under Fair Use

Sarojini Naidu

Sarohini Naidu was born Sarojini Chattapadhyay. She received her education from the University of Madras at King’s College, London. She would go on to study at Girton College, Cambridge. During her time in England, she became familiar with the suffragist movement, and she continued her political interests in India. She became the first woman to be president of the Indian National Congress and appointed Indian state governor. She was a political activist, feminist, and poet. Her writing was very influential and attracted many leading intellectuals to her salon in Bombay. She went on to become a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1914. The Golden Threshold (1905) was the first of three volumes of poetry she published. Due to the musical quality of her work, which critics have compared to Walt Whitman and the Song of SOlomon, she has been given the title the Nightingale of India.

Consider while reading:

- What magical elements are present in Naidu’s work? What is the effect of those elements in the poetry?

- How is Naidu’s work similar to Walt Whitman’s work?

- Describe the musical qualities you find in Naidu’s work.

Read the full version of The Golden Threshold on Project Gutenberg: The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Golden Threshold, by Sarojini Naidu

Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie was born in Bombay (now Mumbai). His education was primarily British. He attended the Rugby School and studied at King’s College, Cambridge. While his first novel, Grimus (1975), was not well received, his second novel, Midnight’s Children (1981) was critically acclaimed. After its publication he became a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1983. Rushdie went onto publish other critically praised novels, such as Shame (1983). However, his is probably best known for his work, Satanic Verses (1988) and the backlash it garnered from Muslim groups in Pakistan, Egypt, and Iran for his depiction of the Prophet Muhammad and the Koran. Some groups went as far as calling for Rushdie’s death. Consequently, Rushdie went into hiding with his family. In 1998, the Iranian government renounced its death threats, adn Rushdie and his family cam eout of hiding the following year. “The Perforated Sheet” is from his second novel, Midnight’s Children. The novel has element so magical realism, postcolonial fiction, and postmodernism. Critics often compare it to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Rushdie pairs the magical elements of the text with a perspective that is distinctly Indian, weaving traditional Indian elements through the work.

The Perforated Sheet

I WAS BORN in the city of Bombay … once upon a time. No, that won’t do, there’s no getting away from the date: I was born in Doctor Narlikar’s Nursing Home on August 15th, 1947. And the time? The time matters, too. Well then: at night. No, it’s important to be more … On the stroke of midnight, as a matter of fact. Clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as I came. Oh, spell it out, spell it out: at the precise instant of India’s arrival at independence, I tumbled forth into the world. There were gasps. And, outside the window, fireworks and crowds. A few seconds later, my father broke his big toe; but his accident was a mere trifle when set beside what had befallen me in that benighted moment, because thanks to the occult tyrannies of those blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades, there was to be no escape. Soothsayers had prophesied me, newspapers celebrated my arrival, politicos ratified my authenticity. I was left entirely without a say in the matter. I, Saleem Sinai, later variously called Snotnose, Stainface, Baldy, Sniffer, Buddha and even Piece-of-the-Moon, had become heavily embroiled in Fate—at the best of times a dangerous sort of involvement. And I couldn’t even wipe my own nose at the time.

Now, however, time (having no further use for me) is running out. I will soon be thirty-one years old. Perhaps. If my crumbling, overused body permits. But I have no hope of saving my life, nor can I count on having even a thousand nights and a night. I must work fast, faster than Scheherazade, if I am to end up meaning—yes, meaning— something. I admit it: above all things, I fear absurdity.

And there are so many stories to tell, too many, such an excess of intertwined lives events miracles places rumors, so dense a commingling of the improbable and the mundane! I have been a swallower of lives; and to know me, just the one of me, you’ll have to swallow the lot as well. Consumed multitudes are jostling and shoving inside me; and guided only by the memory of a large white bedsheet with a roughly circular hole some seven inches in diameter cut into the center, clutching at the dream of that holey, mutilated square of linen, which is my talisman, my open-sesame, I must commence the business of remaking my life from the point at which it really began, some thirty-two years before anything as obvious, as present, as my clock-ridden, crime-stained birth.

(The sheet, incidentally, is stained too, with three drops of old, faded redness. As the Quran tells us: Recite, in the name of the Lord thy Creator, who created Man from clots of blood.)

One Kashmiri morning in the early spring of 1915, my grandfather Aadam Aziz hit his nose against a frost-hardened tussock of earth while attempting to pray. Three drops of blood plopped out of his left nostril, hardened instantly in the brittle air and lay before his eyes on the prayer-mat, transformed into rubies. Lurching back until he knelt with his head once more upright, he found that the tears which had sprung to his eyes had solidified, too; and at that moment, as he brushed diamonds contemptuously from his lashes, he resolved never again to kiss earth for any god or man. This decision, however, made a hole in him, a vacancy in a vital inner chamber, leaving him vulnerable to women and history. Unaware of this at first, despite his recently completed medical training, he stood up, rolled the prayer-mat into a thick cheroot, and holding it under his right arm surveyed the valley through clear, diamond-free eyes.

The world was new again. After a winter’s gestation in its eggshell of ice, the valley had beaked its way out into the open, moist and yellow. The new grass bided its time underground; the mountains were retreating to their hill-stations for the warm season. (In the winter, when the valley shrank under the ice, the mountains closed in and snarled like angry jaws around the city on the lake.)

In those days the radio mast had not been built and the temple of Sankara Acharya, a little black blister on a khaki hill, still dominated the streets and lake of Srinagar. In those days there was no army camp at the lakeside, no endless snakes of camouflaged trucks and jeeps clogged the narrow mountain roads, no soldiers hid behind the crests of the mountains past Baramulla and Gulmarg. In those days travellers were not shot as spies if they took photographs of bridges, and apart from the Englishmen’s houseboats on the lake, the valley had hardly changed since the Mughal Empire, for all its springtime renewals; but my grandfather’s eyes—which were, like the rest of him, twenty-five years old—saw things differently … and his nose had started to itch.

To reveal the secret of my grandfather’s altered vision: he had spent five years, five springs, away from home. (The tussock of earth, crucial though its presence was as it crouched under a chance wrinkle of the prayer-mat, was at bottom no more than a catalyst.) Now, returning, he saw through travelled eyes. Instead of the beauty of the tiny valley circled by giant teeth, he noticed the narrowness, the proximity of the horizon; and felt sad, to be at home and feel so utterly enclosed. He also felt—inexplicably—as though the old place resented his educated, stethoscoped return. Beneath the winter ice, it had been coldly neutral, but now there was no doubt; the years in Germany had returned him to a hostile environment. Many years later, when the hole inside him had been clogged up with hate, and he came to sacrifice himself at the shrine of the black stone god in the temple on the hill, he would try and recall his childhood springs in Paradise, the way it was before travel and tussocks and army tanks messed everything up.

On the morning when the valley, gloved in a prayer-mat, punched him on the nose, he had been trying, absurdly, to pretend that nothing had changed. So he had risen in the bitter cold of four-fifteen, washed himself in the prescribed fashion, dressed and put on his father’s astrakhan cap; after which he had carried the rolled cheroot of the prayer-mat into the small lakeside garden in front of their old dark house and unrolled it over the waiting tussock. The ground felt deceptively soft under his feet and made him simultaneously uncertain and unwary. “In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful …”—the exordium, spoken with hands joined before him like a book, comforted a part of him, made another, larger part feel uneasy—“… Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Creation …”—but now Heidelberg invaded his head; here was Ingrid, briefly his Ingrid, her face scorning him for this Mecca-turned parroting; here, their friends Oskar and Ilse Lubin the anarchists, mocking his prayer with their anti-ideologies—“… The Compassionate, the Merciful, King of the Last Judgment! …”—Heidelberg, in which, along with medicine and politics, he learned that India—like radium—had been “discovered” by the Europeans; even Oskar was filled with admiration for Vasco da Gama, and this was what finally separated Aadam Aziz from his friends, this belief of theirs that he was somehow the invention of their ancestors—“… You alone we worship, and to You alone we pray for help …”—so here he was, despite their presence in his “head, attempting to reunite himself with an earlier self which ignored their influence but knew everything it ought to have known, about submission for example, about what he was doing now, as his hands, guided by old memories, fluttered upwards, thumbs pressed to ears, fingers spread, as he sank to his knees—“… Guide us to the straight path, The path of those whom You have favored …” But it was no good, he was caught in a strange middle ground, trapped between belief and disbelief, and this was only a charade after all—“… Not of those who have incurred Your wrath, Nor of those who have gone astray.” My grandfather bent his forehead towards the earth. Forward he bent, and the earth, prayer-mat-covered, curved up towards him. And now it was the tussock’s time. At one and the same time a rebuke from Ilse-Oskar-Ingrid-Heidelberg as well as valley-and-God, it smote him upon the point of the nose. Three drops fell. There were rubies and diamonds. And my grandfather, lurching upright, made a resolve. Stood. Rolled cheroot. Stared across the lake. And was knocked forever into that middle place, unable to worship a God in whose existence he could not wholly disbelieve. Permanent alteration: a hole.

The young, newly-qualified Doctor Aadam Aziz stood facing the springtime lake, sniffing the whiffs of change; while his back (which was extremely straight) was turned upon yet more changes. His father had had a stroke in his absence abroad, and his mother had kept it a secret. His mother’s voice, whispering stoically: “… Because your studies were too important, son.” This mother, who had spent her life housebound, in purdah, had suddenly found enormous strength and gone out to run the small gemstone business (turquoises, rubies, diamonds) which had put Aadam through medical college, with the help of a scholarship; so he returned to find the seemingly immutable order of his family turned upside down, his mother going out to work while his father sat hidden behind the veil which the stroke had dropped over his brain … in a wooden chair, in a darkened room, he sat and made bird-noises. Thirty different species of birds visited him and sat on the sill outside his shuttered window conversing about this and that. He seemed happy enough.

Copyright © 2010 by Salman Rushdie (Excerpt from Midnight’s Children | Penguin Random House Canada)

ARCHITECTURE

Varanasi- Sacred City

Video URL: https://youtu.be/JoC_x3Hzkkc?si=SMCFXCClRRsfqZuB

Terminus, Mumbai

Palatial architecture meant for daily use

Countless passengers and goods have travelled from the railway platforms of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (Mumbai, India), since it was constructed for the British colonial government in 1878. With its gargoyles, griffins, domes, and towers, the Terminus recalls all at once a palace (in its scale), a political capitol (in its great central dome), a grand hotel (in its accommodation of travelers), and a cathedral (in its gothic tracery). In its political impetus and its grandeur, the Terminus was designed to express British colonial authority in India. Railways were one of the economic engines of the 19th century, and an essential tool for colonial administration and authority.

London in Bombay

Victoria Terminus echoes the Saint Pancras Railway Station in London, a polychrome Gothic Revival confection that had been finished some years earlier.

Like Saint Pancras, the Terminus in Mumbai is encrusted with decorative architectural references drawn from centuries of European history. A short list includes delicate Gothic quatrefoils, ancient Roman-style roundels with bust portraits, and thick Romanesque piers.

The Terminus was originally named for Queen Victoria, the 19th century British monarch, who counted India among her colonies. In 1996 the Terminus was renamed in honor of Chhatrapati Shivaji, the royal title of a seventeenth-century Indian ruler named Shivaji who’s legacy later became associated with India’s independence movement from British colonial rule.

Building empire

Construction on the Terminus began in 1878 and took a decade to complete. It replaced a modest existing railway station and served as the headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsular Railroad. The development of railways in India was well underway when Mumbai’s importance as a trading port significantly increased due to the opening of the Suez Canal (a waterway that connects the Mediterranean to the Red Sea) in 1869 which allowed quicker seafaring to England. The Terminus connected Mumbai (known then as Bombay) to a growing network of railways across the country and allowed for the transport of goods meant for export to the docks of Bombay harbor.

Until 1858, British commercial operations in the Indian Ocean had been administered by the East India Company, a trading firm that had established small merchant posts (known as factories) in India as early as 1611. Although the Company’s competitors—the Dutch and Portuguese trading companies—were already in India by that time, the British East India Company would become a dominant force in Indian Ocean trade.

As the once powerful Mughal empire began to wane, British influence grew. The Company increased its territorial holdings through military operations, by installing puppet monarchs and by annexing princely states. An uprising against the East India Company’s oppressive rule led to the First Indian War of Independence in 1857—an event which the British referred to as a mutiny. British forces prevailed in the bloody conflict and exiled the last Mughal ruler from India. In 1858 the administration of the colony came under the direct control of the British Crown.

Bombay Gothic

The Portuguese had gifted seven islands in the Bombay archipelago to Britain in 1662, on the occasion of the marriage of the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza and the English king Charles II. By the mid-nineteenth century, extensive land reclamation had turned these islands into a single landmass. As the strategic importance, economy, and population of Bombay grew, so too did the interest in building in the city’s open spaces. New constructions were supported by both the Bombay Presidency (as the regional colonial administration was known) and private individuals; several Indian philanthropists were involved in the funding of some of the city’s most important buildings.

Gothic Revival—an architectural movement inspired by medieval Gothic architecture and that was popular in England—was preferred over the Neoclassical style in nineteenth-century Bombay in part because, in the wake of the American Revolution (begun 1776) and the French Revolution (begun 1789), Neoclassical architecture had become associated with Enlightenment ideas of self rule. In contrast, the Gothic style was associated with divine authority—ideal symbolism for colonial occupation. Mumbai’s law courts, university buildings, and municipal offices were all inspired by the Gothic Revival style.

The Terminus

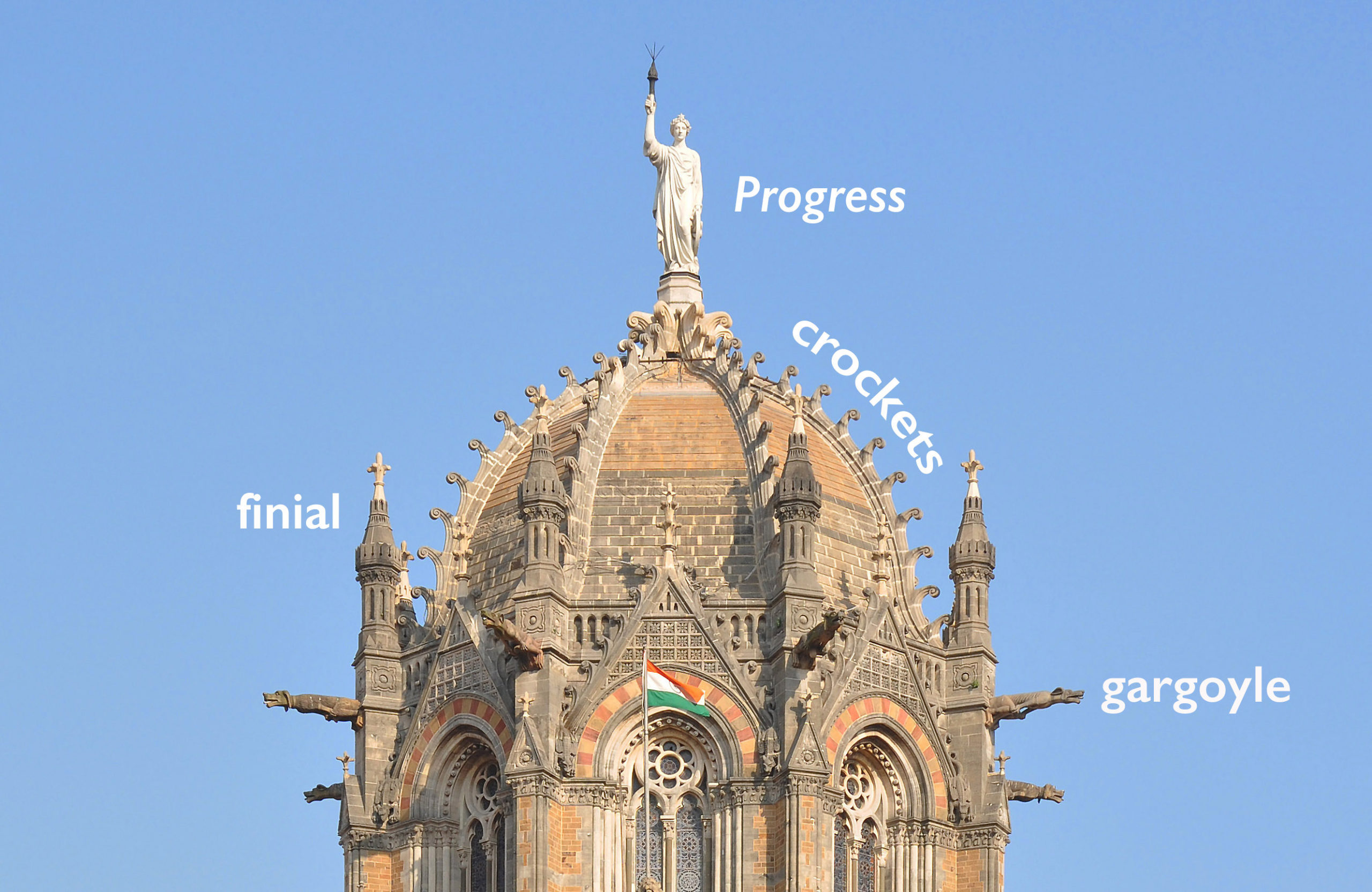

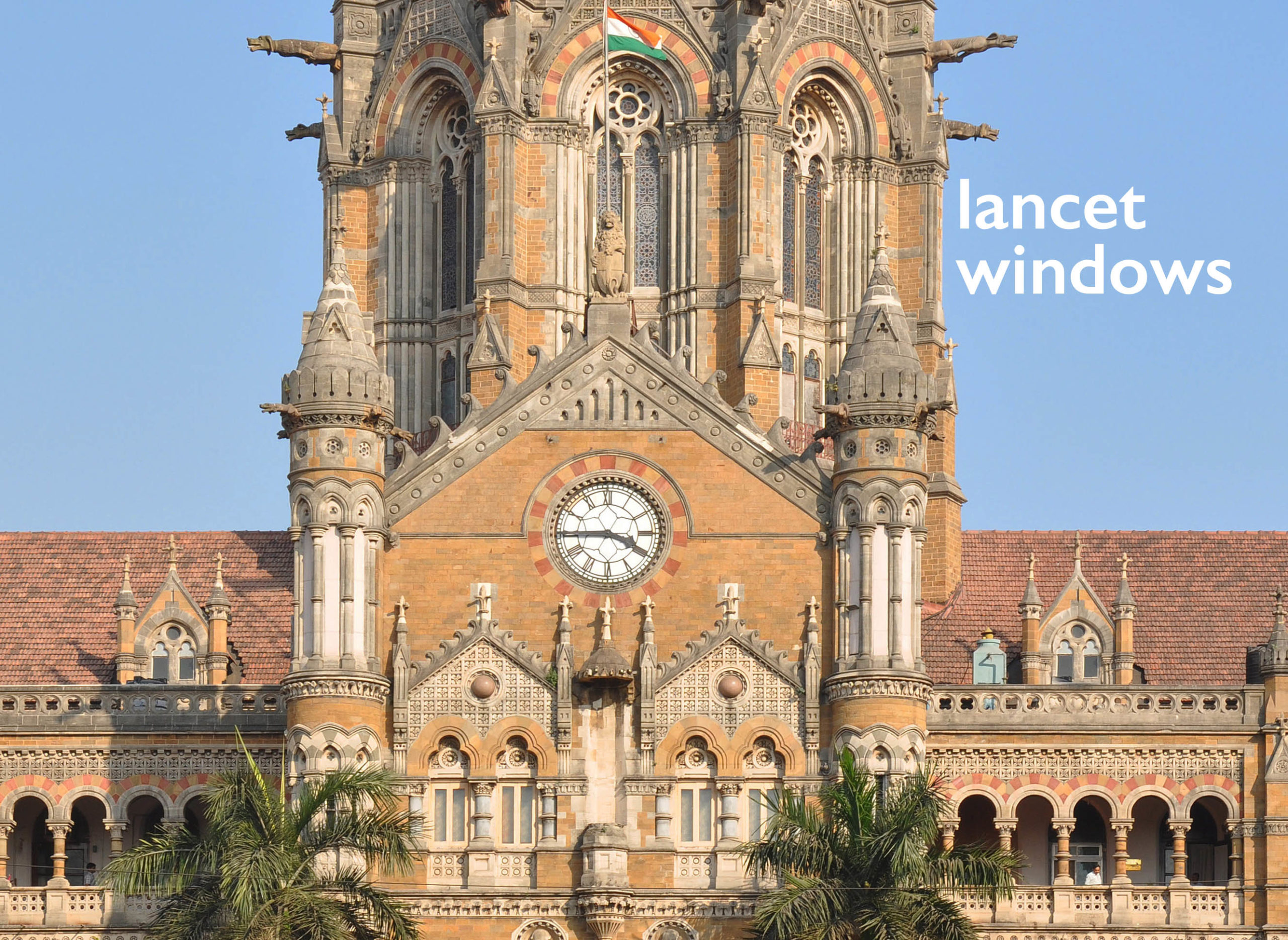

The Terminus, with its Indic and Gothic features, was designed by F.W. Stevens, and the engineers Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan. It is considered the foremost example of Gothic Revival in Mumbai. The building is massive and reaches the imposing height of an estimated 330 feet tall. It’s façade forms a U that hugs the entry courtyard. The train shed is not aligned with the passenger terminal, but is placed at the left of the building. Marking the center of the main building, a prominent dome rises ringed with projecting gargoyles, a fanciful detail found on Gothic cathedrals. The dome is ribbed with crockets (curled leaf forms commonly found in English Gothic churches) and it is topped with a fourteen-foot tall allegorical figure of Progress, a central justification used by British for their rule in India.

Beneath the dome are paired lancet windows below a small rose window, all filled with stained glass as can be seen at the medieval cathedral at Chartres. Below the windows, a pedimented (triangular) façade flanked by turrets (small towers) projects from the central part of the building. At the center of this pediment, an enormous clock outlined with alternating red and yellow sandstone (a motif repeated across the building) takes the place of the rose window that would be here, had this been a medieval church. And like a Gothic cathedral, almost every part of the façade is topped with finials.

Despite this truly riotous program of ornamentation, the alternation between perforation and solid stone walls, between angular and rounded forms, and the use of alternating polychromy, all emphasize the building’s essential order and symmetry.

Annotated façade, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0); Dome with annotation, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, begun 1878, Mumbai (photo: Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Polychrome masonry was preferred for the exterior of the Terminus as the natural colors of the stones used is more permanent than paint, especially given the region’s torrential rains. Various types of stone were used in the construction and decoration of the Terminus, including red and yellow sandstone, limestone, red, blue, and yellow basalts, granite, and marble. This rich palette of colors fit well with theories of the Gothic recently popularized by the influential English critic John Ruskin.

Two heraldic animals—a lion and a tiger that symbolize Britain and India—respectively flank entrance gates that open onto the garden courtyard just in front of the terminus. Carved animals, including monkeys, rats, owls, rabbits, and cobras, are found in unexpected places such as in walkways, friezes, column capitals, and in tympana above doorways.

The school championed the amalgamation of select Indian and western traditions. If the carved animals are playful references to the marginalia found in medieval manuscripts or the playful sculptures found on medieval churches, and the foliage that they emerge from is indeed Indian in origin, then the terminus is indeed a deliberate amalgam of Indian and European inspiration. It is worth noting that animals are also present in the stonework at St. Pancras in London.

Once inside, the heavy decorative stonework echos the pre-Gothic, Romanesque style, especially in the door jambs and heavy bundled colonnettes. But here as well, European and Indian motifs meet as can be seen in the use of stacked corbel brackets and cusped arches. The entry space is relatively narrow given the scale of the exterior façade, but it soon opens up high above the visitor’s head.

The main dome rises above a rectilinear shaft lined with partly suspended stairs that cantilever out from the walls. Above, the dome is structured by ribs that spring from corbels and meet at its center. Light enters through tall lancet windows filled with stained glass and gives this space a sense of airiness that is somewhat deceiving, as the dome sits on an octagonal drum atop ornamented squinches. These squinches play an important role. They are located at the corners of the four-walled shaft and transition to the eight-sided dome directly above. This solution can be seen in Sultanate architecture, such as the dome of the 14th-century Alai Darwaza, at the Qutb archaeological complex.

The main hall has tall granite piers with attached columns of varying heights and slender colonnettes. Each column is topped with foliate capitals that were carved in-situ. [3] The hall’s eight-part ribbed vaults (made of wood) were originally painted blue with golden stars to mimic a starry sky—a tradition found in many Gothic churches. All this forms what is essentially a two-aisled nave that is flanked by side aisles defined by a nave arcade made of pointed arches (the ticketing office fills one of the side aisles, while the other opens onto the train platforms). Above are galleries, as you might expect to see in a Gothic Cathedral.

The original rich coloring of the stone and tile-work has faded, but the polychromatic scheme of the interior is still pronounced and impressive. Although much of the ironwork has been replaced, gilded balustrades and railings would have added to the opulence of the Terminus in its early years.

Progress

With its muted Indic features (domes, ornamented squinches, and chaitya arches), the Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus embraces an eclectic Gothic style that is a valuable example of the Indo-Sarascenic—in the selective utilization of Indian architectural precedents, the selective representation of India, and in the framework of empire on which the design of the building is predicated.

For the British Raj, the city of Bombay was their mercantile jewel and they were as confident in their self-perceived role as the city’s visionaries as the allegorical figure of Progress atop the Terminus. Today, the Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus is an emblem of change and it has pride of place at the heart of the city. It is a historical landmark, a UNESCO world heritage site, and an important resource for the millions of people who regularly use it.

Progress now looks over a city transformed, an empire dismantled, and the world’s largest democracy.

Copyright: Dr. Arathi Menon, “F.W. Stevens with Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai,” in Smarthistory, June 7, 2021, accessed May 31, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/shivaji-terminus-mumbai/.

PERFORMING ARTS

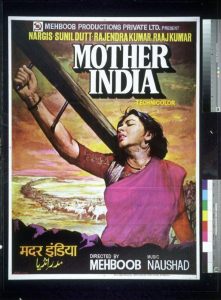

World Cinema

Video URL: https://youtu.be/mpQrcxfNl-o?si=A7Tqg4aovVfdoVZ_

Indian Classical Music

North Indian Classical Music (Hindustani sangita)

Music from the Indian subcontinent is one of the non-Western repertories that has fascinated Western musicians and audiences in recent decades. Improvisation is central to the performance of North Indian classical music (Hindustani music) and is mastered only after years of study with a guru. The skeletal elements from which the improvisation springs are the raga, an ascending and descending pattern of melodic pitches, and the tala, the organization of rhythm within a recurring cycle of beats. Rather than the 12-semitone octave of Western classical music, Indian music divides the octave into 22 parts. Although only some of those 22 pitches are used in a particular raga, the complexity and subtlety of Indian melody is attributable in part to this relatively large vocabulary of pitch material. With respect to temporal organization, Indian music organizes spans of time into cycles of beats, somewhat comparable to the Western concept of meter.

But whereas Western composers have worked predominantly in a framework of time spans divided into repeated cycles of two, three, or four beats, the time span of a tala is comprised of units of variable length, for example, a 14-beat tala of four plus three plus four plus three beats. A tala may also be of enormous duration in comparison with a Western measure, which rarely exceeds a few seconds in length.

There are hundreds of talas and thousands of ragas. Each raga has specific extra-musical associations such as a color, mood, season, and time of day. These associations shape the performer’s approach to and the audience’s experience of an improvisation, which can last from a few minutes to several hours. Indian music also has an important spiritual dimension and its history is intimately connected to religious beliefs and practices. As stated by the great sitarist Ravi Shankar, “We view music as a kind of spiritual discipline that raises one’s inner being to divine peacefulness and bliss. The highest aim of our music is to reveal the essence of the universe it reflects….Through music, one can reach God.”

The typical texture in Indian music consists of three functionally distinct parts:

- A drone, the main pitches of the raga played as a background throughout a composition

- Rhythmic improvisations performed on a pair of drums

- Melodic improvisations executed by a singer or on a melody instrument.

One of the most common melody instruments is the sitar, a plucked string instrument with a long neck and a gourd at each end, six or seven plucked strings, and nine to thirteen others that resonate sympathetically. The melody instrument or voice is traditionally partnered by a pair of tablas, two hand drums tuned to the main tones of the pitch pattern upon which the sitar melody is based. The drone instrument is often a tambura, a plucked string instrument with four or five strings each tuned to one tone of the basic scale and plucked to produce a continuous, unvarying drone accompaniment.

A raga performance traditionally opens with the alap, a rhapsodic, rhythmically free introductory section in which the melody instrument is accompanied only by the drone. Microtonal ornaments and slides from tone to tone are typical elements of a melodic improvisation. The entrance of the drums marks the second phase of the performance in which a short composed melodic phrase, the gat, recurs between longer sections of improvisation. Ever more rapid notes moving through extreme melodic registers in conjunction with an increasingly accelerated interchange of ideas between melody and drums produces a gradual intensification as the performance progresses to its conclusion.

South Indian Classical Music (Karnataka sangita)

South Indian classical music (Karnatic or Carnatic music) evolved from ancient Hindu traditions and is relatively free of the Arabic and Islamic influences that contribute to Hindustani music. Karnatic music is primarily vocal and the texts devotional in nature (often in Sanskrit). The instrumental music consists largely of performances of vocal compositions with a melody instrument replacing the voice and staying within a limited vocal range. It is important to note that the vocal style is so advanced that it seems almost instrumental in nature. One could say in Karnatic music that vocal and instrumental styles merge into one. Works in this tradition are normally composed, as opposed to the improvised Hindustani tradition, with new compositions being written every day. Four Karnatic composers of great importance are Purandara Dasa (1494 – 1564), Shayama Shastri (1762 – 1827), Tyagaraja (ca.1767 – 1848), and Muttusvami Dikshitar (1775 – 1835).

Karnatic music uses the same system of raga (scale) and tala (meter) as found in the north, but the systems for classifying raga and tala are more highly developed and consistent, thanks to a long period of growth with a minimum of influence from the outside.

Just as Hindustani instrumental music often follows the formal outline of an alap (slow meditative section exploring the raga), followed by a gat (faster section with percussion accompaniment), many Karnatic compositions are in the form Pallavi: (Opening Section), Anupallavi: (Middle Section), Charanam: (Concluding Section) with an abbreviated pallavi serving as a refrain between subsequent sections and concluding the piece. Towards the end of the composition an improvised section, called the svara kalpana, is often inserted where the vocalist expands on the pitches in the raga while singing with “sa re ga ma” syllables instead of the text. This improvised singing may alternate with a melody instrument, such as a violin, imitating the singer.

Two Western instruments have become a standard part of Karnatic music, the aforementioned violin for melodic use and the hand-pumped harmonium for playing the sustained drone pitches. A present-day concert ensemble might include a lead vocalist, a violin, a mridangam (a two-headed drum functioning as the tabla does in Hindustani music), a ghatam (a large mud pot reinforcing the tala) and one or two tambura (large string instruments performing the drone pitches).

Bhangra

A music and dance style originating in the Punjab region of northwest India, Bhangra has influenced, and been combined with, contemporary forms in the Punjabi Indian diaspora. As a traditional/folk style, it is typically performed as part of harvest celebrations and was eventually used during other occasions, such as weddings and festivals. The lively and joyous nature of such events is reflected in both the music and the dance.

Sikhism

Spiritually, the Indian state of Punjab differs from the rest of India where Hinduism (around 80% of the population) and Islam (approximately 15%) are dominant, as the dominant religion is instead Sikhism. The Sikh religion is one of the world’s youngest major religions, having been established in the 15th century, and is practiced by approximately 25 million people worldwide. Sikhs follow the teachings of ten Gurus, which is compiled in their sacred scripture Guru Granth Sahib. Sikh music draws from many of the principles of Indian music, such as raga and tala, and uses some of the instrumentation from the Hindustani tradition. Specific ragas are associated with hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib and Kirtan, a devotional style also found with other religions such as Hinduism, is typically performed at temples and in a call-and-response format that encourages participation.

Instruments

Several traditional instruments are used in both the folk and contemporary popular forms, operating as distinct sonic markers that tie the style to the region even when mixed with Western popular influences. The instruments also differentiate bhangra from those used in Hindustani music, the art music tradition of northern India.

One of the main instruments in Bhangra music is the Dhol, a large two-headed barrel drum typically played with two sticks made of wood or bamboo. A light stick is used to play the higher ‘treble’ head while a curved stick is used to play the bass head. It typically repeats a 4-beat syncopated pattern that the dancers follow.

Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uR8BYSsHihk

Dhol Performers:

Chimta:

The chimta, another rhythm instrument used in Bhangra, is a metal tong with attached jingles. Also used in Punjabi folk styles and Sikh devotional music, in Bhangra is it particularly used to emphasize the downbeat.

Chimta:

Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2Co3QgSEqk

Other Instruments:

The tumbi is a small single-string plucked fiddle that creates a distinctive high-pitched sound. The instrument was featured in 2001 song “Get Ur Freak On” by Missy Elliot, as well as in the example below by Panjabi MC. The algoza is a double end-blown flute where one flute provides the melody and the other a drone.

Bhangra dance is quite vigorous with constant motion performed by dancers in brightly colored clothing, called vardiyaan, that reflect the celebratory contexts of the performances. The attire is loose fitting to allow for movement of the dancers. A common element in Bhangra is a wide stance, often with one leg elevated to waist height. Depending on the move being executed, dancers will switch between their legs after a fixed number of beats. Hands are frequently held high with the palms out and the thumb and index finger joined.

Traditional Bhangra with dancers dressed in vardiyaan:

Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-prTJHNRCGA

Some basic Bhangra dance movements:

Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=44&v=Ax3LF-EPvKU&feature=emb_logo

Popular Bhangra

A new version of Bhangra emerged not in India but in the Punjabi diaspora, particularly the United Kingdom. Throughout the twentieth century Punjabi have immigrated to new lands, particularly after the partition of colonial British Raj into the independent states of India and Pakistan in 1947. The Punjab region was divided amongst the two nations, the division largely along religious lines with Moslems in Pakistan and Sikhs and Hindus in India. Displacement occurred on both sides of the newly formed border and in the subsequent decades more Punjabi Indians immigrated to the United Kingdom and other former members of the British Commonwealth. It is in this diaspora of Punjabi Indians removed from their homeland where a new version of Bhangra was formed.

A new style emerged during the mid-1980s that mixed elements of the folk tradition with contemporary popular styles and techniques, especially from hip hop, reggae, and electronic dance music. The new popular music version maintains many of the characteristic sonic markers of the folk tradition, particularly traditional instruments like the dhol and its signature rhythms. The popular style could either be in the more traditional Punjabi language or in English, the primary language of the new lands where this new version of bhangra formed. Similar to the folk version, the popular version is largely used for festive occasions, particularly weddings and festivals, and the vigor of the original accompanying dance has been preserved. The hybrid nature of the popular style of bhangra reflects the hybrid identity of the new generation of Punjabi Sikhs, who in many cases have been raised entirely outside of India.

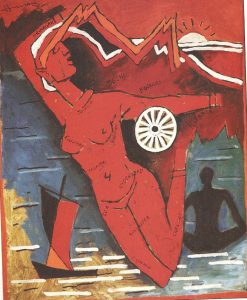

VISUAL ARTS

Photographic Views of India

Photography’s early history in India

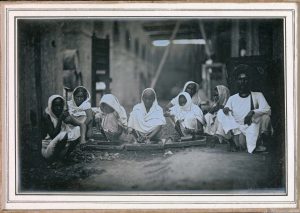

Photograph inscribed “Women Grinding Paint,” Calcutta, India, c. 1845, daguerreotype, 9.4 x 14.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

On August 19, 1839, the invention of a new photographic method, the Daguerreotype process, was announced to the public at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. In December of the very same year, the Bombay Times in India published three articles on the arrival of the new Daguerreotype camera. As early as 1840, hardly a year after photography had first developed in Europe, the Calcutta firm of Thacker & Company were importing and advertising the sale of the Daguerreotype camera in the daily paper Friend of India. Far from a belated version of European photography, photography in India developed rapidly and in parallel with European photographic practices. In fact, the new technology of photography was very well received in nineteenth-century India and would be taken up by aspiring amateur photographers, commercial photographers, photojournalists, and colonial state officials with much enthusiasm. Coinciding with the expansion of British imperial rule, photography lent itself to the geographical and cultural exploration of the British Empire’s colonies. Nineteenth-century photographs thus elucidate the instrumental role of the camera in the study, documentation, and representation of India’s cultures, people, and landscapes during a period of colonial governance.

European photographers in India

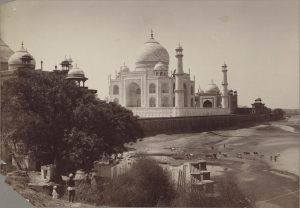

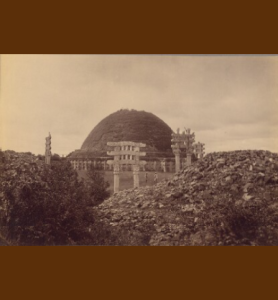

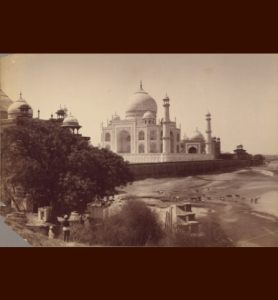

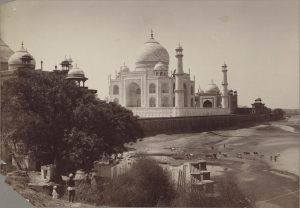

At first, photography served as the leisurely pursuit of wealthy Indians, European officers and travelers, and other aspiring amateur photographers. Dr. John Murray of the Bengal Medical Service was one such amateur photographer. Murray began his experimentations with photography when he moved to the city of Agra (located today in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh) in 1848. During his stay, he produced a series of views of the Mughal monuments of Agra (such as the Taj Mahal), Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri, and other nearby sites, which not only satisfied his own fascination with the technology but contributed to an emergent visual archive of the landscapes and landmarks of India.

Murray achieved recognition for his work when his photographs were published under the titles Photographic Views of Agra and Its Vicinity and Picturesque Views of the North Western Province of India in 1857 and 1859 respectively. These early photographs of India allowed those who had not traveled to the subcontinent to see and know India from the comfort of their own home.

India and the picturesque

The 1860s saw the growing dominance of commercial photography in India, as European photographers, following in the footsteps of earlier traveling artists, increasingly visited India to produce photographs for sale and publications. European artists first began to travel to India after the 1750s and disseminate visual information about the country’s landscapes, architecture, and peoples—alongside the expansion of European colonial powers in India. During the nineteenth century, European artists, both professional and amateur, journeyed to India in even greater numbers in search of picturesque scenery to be captured by the painter’s brush and, thereafter, the photographer’s camera.

Like earlier landscape painters, travel photographers from Britain held certain expectations of what they hoped to find in the regions to which they traveled and framed their views of the country through specific aesthetic principles known as the picturesque. Components of picturesque landscapes included a body of water, strategically placed foliage, a rustic bridge, evidence of human presence, and more broadly, a sense of sublime, awe-inspiring beauty. The picturesque was devised in the eighteenth century by English critics such as William Gilpin, whose guidebooks defined the manner in which nature should be visually represented.

These key features are present in the work of Samuel Bourne—one of the most important British commercial photographers working in nineteenth-century India who created hugely successful photographic studios in Shimla (1863), Calcutta (1867), and Bombay (1870) with his partner Charles Shepherd. An 1865 photograph showing Gangootri from one of Bourne’s three arduous treks to the Himalayas, for example, depicts a gently flowing river, a makeshift wooden bridge, and a stone temple or dwelling set against the backdrop of imposing mountainous terrain, underlying the photographer’s reliance on the aesthetic parameters of the picturesque.

Bourne’s widely disseminated picturesque photographs of India’s temples, mountain ranges, cityscapes, and landscapes played a vital role in shaping foreign perceptions of the subcontinent. Picturesque landscape views produced a simplified vision of India, seemingly untouched and in want of modern civilization. Within this aesthetic framework, Indians were reduced to mere aesthetic elements, devoid of agency and individuality. In the context of European colonialism, the picturesque aesthetic can, in this way, be read as an ideological tool mobilized to support colonial intervention.

An Indian photographer